This chapter begins by considering the etymology of “globalization” and how the phenomenon has been perceived by the public and in the media. It then reviews how globalization has been defined, with a focus on the academic literature, and with particular emphasis on business and economics. It goes on to consider how globalization might be measured at the country level and argues for a primary focus on the depth (also referred to as intensity) and the breadth (also referred to as extensity) of countries’ international interactions. Measuring globalization on this basis – as we do biennially for the DHL Global Connectedness Index – suggests that, overall, globalization decreased during the economic crisis of 2008 and has been slow to recover. This distinguishes our index from other leading globalization indexes with which comparisons are feasible.

Origins and Opinions

The word “globalization” is a relatively recent addition to the English lexicon. It first appeared in Webster’s Dictionary in 1961 (Reference Kilminster and ScottKilminster 1997, 257), and according to the current edition, its first use came a decade earlier in 1951. Its roots can be traced back to the terms “global” (which took on the meaning of “world scale” in the late nineteenth century) and “globalize” (which appeared in the 1940s) (Merriam-Webster 2015). By contrast, its cousin, “international,” is much older, having been introduced by Jeremy Bentham in 1789 (Reference BenthamBentham 1823). Bentham needed the term to describe the legal relations between sovereign nations and people from different nations (Reference JanisJanis 1984, 409).

The ideas that now find their expression in terms of globalization are older than the word itself, of course, just as relationships between sovereign states existed before Jeremy Bentham gave them a name. David Livingstone remarked in 1872 that “the extension and use of railroads, steamships, telegraphs, break down nationalities and bring peoples geographically remote into close connection commercially and politically. They make the world one, and capital, like water, tends to a common level” (Reference Livingstone and WallerLivingstone and Waller 1874, 215). Jules Verne published Around the World in 80 Days in Reference Verne and Towle1873, bringing the idea of circling the world by steamship and railway into the public imagination. Verne’s Phileas Fogg speaks of the world having grown smaller as a result of the technology of his day (Reference Verne and TowleVerne 1873) – an idea that still resonates with today’s digital natives, many of whom are fans of Thomas Friedman’s The World Is Flat (Reference FriedmanFriedman 2005). And speaking of the age that ended with World War I, John Maynard Keynes was able to write that “the inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit, and reasonably expect their early delivery upon his doorstep” (Reference KeynesKeynes 1919, 9).

Discussion of potential harms associated with these trends also predates the term “globalization.” The expression “World War” was first used before either of the conflicts we now know by that name. It was first mentioned in 1898 in the New York Times and was used alternately with “The Great War” as the appellation for the first such war from its outbreak in 1914 (Reference HarperHarper 2015). Meanwhile, worries about foreign ownership began as early as the late nineteenth century. In the 1880s and 1890s, Americans became angry at the increased foreign ownership of US land, while US foreign direct investment in Europe created resentment there (Reference JonesJones 1996, 253). In 1901, English journalist W. T. Stead published a book called The Americanization of the World and by the 1920s, Japanese writers worried about the Americanization of Japan (Reference Rydell and KroesRydell and Kroes 2005, 9). Fears of “Coca-Colonization” date back at least to the 1940s (Reference JonesJones 1996, 251).

It was only in the past twenty years, however, that “globalization” became the word of choice used to describe these ideas: In the early 1990s, the US Library of Congress catalog listed less than fifty publications per year related to globalization, but from 2002 to 2014, there were more than a thousand every year.1 Indeed, the fascination with globalization has itself become a global phenomenon, with every major world language having developed a word for it, from 全球化 (quánqiúhuà) in Chinese to küreselleşme in Turkish (Reference ScholteScholte 2005).2

Public opinion, on balance, is positive toward at least some aspects of globalization – especially in emerging economies – but is changeable and subject to important caveats. The Pew Spring 2014 Global Attitudes Survey reports a global median (based on data from forty-four countries) of 81 percent of respondents believing “growing trade and business ties” to be either very good or somewhat good for their countries. However, only 45 percent have a similar view about foreign companies buying domestic ones, and a mere 26 percent see trade as lowering prices (Pew Research Center and Roper Center 2014). Surveys by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs indicate that most Americans “believe that globalization, especially the increasing connections of our economy with others around the world” is mostly good for the United States, and depict a trend of falling public support for globalization from 2004 to 2010, followed by a rising trend through 2014 (Reference Smeltz, Daalder and KafuraSmeltz, Daalder, and Kafura 2014, 37).

Media reports on globalization in the United States, however, have tended toward the negative. Using the AlchemyAPI sentiment analysis engine, we looked at articles matching the search term “globalization” in the New York Times, Washington Post, and Wall Street Journal over the period 2005–2015. All three publications showed a consistent tendency toward negative coverage, although the Wall Street Journal has been less negative than the others since 2012. Interestingly, however, using the same parameters with three English-language Chinese publications, China Daily, Shanghai Daily, and Xinhua News, showed a much more positive stance. Similar results were obtained using two other sentiment analysis engines.3

These tendencies in public and media sentiment are, of course, just averages that mask a wide dispersion of views about globalization, reflecting, in part, varying conceptions of the phenomenon itself. To attempt to bring greater clarity, we need to start by being explicit about how we choose to define the term, and why. We will then operationalize its measurement at the country level.

Defining Globalization

Journalists, social commentators, and academics have proposed a multitude of definitions of globalization. The term has been used to denote liberalization, Westernization, homogenization, economic growth and decline, equality and inequality, and so on.

To get a handle on the diversity of definitions, it is useful to start with previously assembled compendia of them. Given our interest in business and the scholarly focus of this book, we turned to two compendia assembled by business school affiliates, Reference BeerkensEric Beerkens (2006) and Reference Stohl, May and MumbyCynthia Stohl (2005).4 Restricting each author cited in the compendia to one definition, we narrow the list to forty-two definitions. Some of the heterogeneity across them can be illustrated with the word cloud in Figure 1.1.5 Unsurprisingly, “world” is the most common word, with “process,” “new,” “social,” “economic,” and “national,” also standing out. Nevertheless, it is also clear that there were many other associations as well.

Figure 1.1 Word cloud showing definitions of globalization.

Given this diversity, an obvious expedient is to concentrate on definitions that have been particularly influential in terms of academic citations. We initially searched Google Scholar for results matching “globaliz OR globalis AND,” followed by the author and year of the definition from Beerkens’s and Stohl’s work. The most cited reference in the general academic literature is Reference AppaduraiArjun Appadurai’s 1996 book Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Beerkens characterizes Appadurai’s definition as “a process of cultural mixing or hybridization across locations and identities” (Reference BeerkensBeerkens 2006, 1).6

However, the phrase that Beerkens uses does not appear in Appadurai’s book. In fact, Appadurai in a private communication indicates that “‘hybridization’ is too weak and general a feature to be a good definition. My own argument in regard to the cultural side of globalization is that ‘cultural heterogenization always outpaces cultural homogenization’” (Appadurai “Defining Globalization” Reference Appadurai2015).

Appadurai is, obviously, one of the leading commentators on one of the key issues around globalization – whether in fact it does lead to cultural homogenization (Reference Appadurai1996). Many of his ideas are also relevant to markets for cultural goods. But they don’t put business and economics at center stage, which is our intention. So we decided to emphasize that body of literature and the definitions cited by academics therein.7

Unfortunately, while Google Scholar is frequently used for this type of work, it covers academic literature very broadly and does not allow searches on particular subjects. In addition, it uses a proprietary algorithm that is subject to some opacity. Google Scholar is designed to prioritize the best matches and find as many matches as possible. Although this may allow a researcher to find scholarly works with relative ease, it is not ideal for more specific searches.8

Noting the issues with Google Scholar, we turned to Business Source Complete, which has a more straightforward search algorithm and better-documented features, and also focuses on business and economics literature. In an attempt to be more systematic about finding references to the actual definitions, text-mining techniques were used, starting with the development of a set of keywords from each definition. To determine if the definition itself is cited, a search was conducted to see if these keywords appeared within forty words of each other, which corresponds to approximately two sentences in English, according to an oft-cited linguistics study (Reference SichelSichel 1974). We limit the search to articles containing the name of the cited author and year together, as well as to those published after 2000 to reduce bias toward older definitions.9

The top result using this method is from Reference Held, McGrew, Goldblatt and PerratonHeld et al.’s 1999 book, Global Transformations: Politics, Economics, and Culture. The definition is as follows:

Globalization can be thought of as a process (or set of processes) which embodies a transformation in the spatial organization of social relations and transactions – assessed in terms of their extensity, intensity, velocity and impact – generating transcontinental or interregional flows and networks of activity, interaction, and the exercise of power.

While Held et al. do not say that globalization is an unstoppable force, as some commentators seem to believe, their language, with its talk of transformation, tends to suggest forward momentum for the process. What is more helpful from our perspective, though, is that their definition starts to suggest ways of measuring globalization: the topic of the next section.

Measuring Globalization

When deciding how to measure a phenomenon, a first critical decision concerns the unit of analysis to use. Globalization can take place – and could, in a sense, be measured – at levels ranging from the very macro down to the individual.10 We begin by looking at globalization at the country level – in terms of interactions between countries11 – although later in this book, we will also explore globalization at the industry, company, and (more selectively) individual levels.

Held et al.’s definition suggests that globalization has four “spatio-temporal dimensions”: extensity, intensity, velocity, and impact (Reference Held, McGrew, Goldblatt and PerratonHeld et al. 1999, 17). This book emphasizes two of their four dimensions: intensity and extensity. Henceforth, we use the term depth for measurements of intensity and breadth for measurements of extensity.

Depth measures how much of an economy’s activities or flows are international by comparing the size of its international flows (and stocks accumulated from prior year flows) with relevant measures of its domestic activity. This tracks the law of semiglobalization, which states that international interactions are significantly less intense than domestic interactions. Chapter 2 demonstrates that most global flows have a depth of under 30 percent.

Previous research has criticized depth measures, since small countries tend to rank much higher on them than large ones (Reference Squalli and WilsonSqualli and Wilson 2011). This is in part a mathematical artifact, as the analogy of Jew-Gentile marriages illustrates. The intensity of such marriages will inevitably be higher for Jews if there are fewer of them than for Gentiles, but that need not imply that Jews are more open to intermarriage.

Many adjustments have been proposed to address this problem, but more important than the details of the differences among them is the distinction between measuring the state of globalization and openness to globalization. As Kam Ki Tang and Amy Wagner put it in the specific context of trade, “if the purpose is to measure trade intensity or trade dependency, then the [trade intensity index] will be an appropriate measure. However, if the purpose is to measure trade openness, it has a limitation of being biased against large economies” (Reference Tang and Wagner2010, 2). Since our aim is to measure the actual level of globalization, we focus on depth (intensity) measures and later regress them on country size and other variables to see if the observed relationships align with a priori expectations.

Breadth, the second integral part of our globalization index, complements depth by looking at how widely the international component of a given type of activity is distributed across countries. In line with the second law of globalization – the law of distance – we expect breadth to be limited by distance effects, with countries interacting more with other countries that are culturally, administratively, geographically, and (often) economically close rather than distant.12

To illustrate the importance of incorporating breadth into assessments of global connectedness, consider the southern African country of Botswana. The trade depth of Botswana is high, with merchandise imports and exports together summing to 102 percent of the country’s GDP. Yet, Botswana’s trade is very limited in its geographic scope: 61 percent of Botswana’s exports went to the UK in 2013. Another 13 percent were sent to neighboring South Africa. Only 1 percent were destined for the world’s largest importer, the United States (Reference Ghemawat and AltmanGhemawat and Altman 2014, 145).

Our conception of breadth deliberately departs from Held et al.’s view of extensity, which emphasizes transcontinental and interregional flows. Our analysis of regionalization indicates that, on average, 53 percent of international trade, capital, information, and people flows take place within rather than between roughly continental regions (Reference Ghemawat and AltmanGhemawat and Altman 2014, 92). While Held et al. suggest excluding such intraregional activity, doing so would yield a severely incomplete picture of countries’ international linkages. Furthermore, there is a great deal of subjectivity in defining regions and even continents to which measures that discard all intraregional data are particularly sensitive. We return to regionalization in Chapter 10, analyzing it there using several region classifications.13

We actually use several types of breadth measures to summarize distributions of interactions, as explained further in Chapter 5. At the country level, our primary breadth measure compares the destinations of a country’s international flows to all other countries’ shares of the same type of flows in the opposite direction. A country would earn the highest possible breadth score for exports if its exports are distributed across destinations in exact proportion to the rest of the world’s imports.14 Higher breadth scores suggest greater indifference to distance. For world-level analysis, we complement this measure with simpler alternatives such as the average distance traversed by international flows and the proportion that take place within versus between regions.

Velocity, as defined by Held et al., is largely a result of developments in transportation and, especially over the past few decades, communications. One of the problems with measuring communications velocity, however, is the movement to real time: (minimal) time lags in communication seem to be asymptoting toward zero and have been headed in that direction for a long time now. Thus, the transatlantic telegraph cable reduced the time that it took for information to travel between New York and London from more than a week to less than an hour in the 1860s (Reference O’Rourke and WilliamsonO’Rourke and Williamson 1999, 219–220; Reference Fouchard and ChesnoyFouchard 2016, 32–33). International transportation lags for physical goods can still range into weeks and even months, but at least in terms of lower bounds, there isn’t evidence of rapid change in the recent period (since 2005) on which our measurement exercise focuses. So given insufficient variation over the time frame we analyze, as well as limitations in data availability across countries, we do not incorporate velocity into our measurement of globalization.

The fourth element highlighted by Held et al., the impact of globalization on social relations and transactions, is crucially important. Indeed, one of us (Reference GhemawatGhemawat 2011) wrote a whole book, World 3.0, on the social impact of globalization and how its side effects might be managed. But impact is not the primary consideration here; the measurement of globalization is. And mixing up measures of the phenomenon itself with measures of its putative implications seems like a bad basis for actually testing those performance implications.

To what types of international interactions should the depth and breadth measures be applied? Although no one master list stands out, there seems to be general agreement that trade, capital, information, and people flows are all worth considering. Thus, Michael Mussa, an economist, highlights “trade, factor movements [of capital and people], and communication of economically useful knowledge and technology” (2000, 9), while anthropologist Arjun Appadurai cites “ideas and ideologies, people and goods, images and messages, technologies and techniques” (Reference Appadurai2000, 5) – and has written, most recently, a book about finance (Appadurai Banking Reference Appadurai2015). In the chapters that follow, a variety of international interactions will be considered, ranging from standard ones such as merchandise trade to nonstandard ones such as patterns of who follows whom on Twitter, but they can all be related to one of the four “pillars” around which we construct the DHL Global Connectedness Index (www.dhl.com/gci): trade, capital, information, and people.

The DHL Global Connectedness Index measures trade based on imports and exports of merchandise and of services. For depth measures, these are normalized by GDP. Capital is measured using data on foreign direct investment (FDI) and portfolio equity. For each of these, we consider stocks of foreign assets and liabilities as well as flows of capital.15 The bases of normalization for the capital depth measures vary: GDP for FDI stocks, gross fixed capital formation for FDI flows, and market capitalization for portfolio equity stocks and flows. Information flows are measured by international internet bandwidth (as a proxy for international internet traffic), international phone calls, and trade in printed publications. People movements are measured using data on migrants, international university students, and tourist arrivals. On the information and people pillars, depth is calculated on a per capita basis (based on overall population except in the cases of international internet bandwidth, which is measured per internet user, and international students, which is compared to total tertiary enrollment).

Once all of the depth and breadth metrics have been calculated, panel normalization is performed and the index is aggregated using an importance-based weighting scheme. Given our aforementioned focus on business and economics, the trade and capital pillars are each assigned 35 percent of the total index weight, and the information and people pillars are each assigned 15 percent. Finally, we apply equal weights to depth and breadth. The technical details are described at greater length in each edition of the DHL Global Connectedness Index.

At a broader level, it is worth adding that the DHL Global Connectedness Index focuses strictly on measuring actual interactions between countries.16 Symmetric to the argument about excluding performance implications, policy enablers are left out of the globalization index so as to enhance its value in policy analysis.

The index is calculated entirely based on hard data, with no reliance on analysts’ opinions or surveys – which is particularly useful given the tendency to globaloney that was mentioned in the introduction and that will be discussed further in Chapter 2. It has come to incorporate more than one million data points covering both depth and breadth across 140 countries that account for 99 percent of the world’s GDP and 95 percent of its population. The inclusion of breadth greatly increases the amount of data required: between all possible country pairs rather than only between each country and the rest of the world.

Other Globalization Indexes

For many years, scholars relied primarily on World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) data on trade and capital flows across borders to determine the level of globalization and the extent to which different countries were “globalized.” Also on offer since the turn of the century are a number of indexes that attempt more multifaceted analysis – of the flows not only of goods and money, but also of people and information – across borders.

The first globalization index to attract significant attention was produced by the consulting firm A.T. Kearney in collaboration with Foreign Policy magazine, and was released in 2001. As that index has not been released since 2007, it will not be addressed further here. There are, however, four other globalization indexes that have been published more than once and continue to be updated: the KOF Index of Globalization, the Ernst & Young (E&Y) Globalization Index (developed in cooperation with the Economist Intelligence Unit), the Maastricht Globalization Index (MGI), and the McKinsey Global Institute Connectedness Index (McK).

These other globalization indexes, to the extent they measure actual interactions rather than their enablers, concentrate almost entirely on depth. An analysis of the fifty-six economies included in all of the indexes shows that the correlation coefficient between depth ranks on the DHL Global Connectedness Index and ranks on the KOF, E&Y, and MGI indexes is between 0.81 and 0.84 (on McK, it is a much lower 0.34 for reasons we will discuss later). By contrast, the correlation coefficient between breadth ranks and ranks on all the other indexes ranges from 0.34 to 0.47. The Ernst & Young Globalization Index added one simple breadth measure – the share of main trading partners in total trade – in its 2012 edition, but the other three indexes incorporate none. The exclusion of breadth from other indexes is particularly noteworthy since the (co)authors of the KOF index and the MGI write that “an important criticism of many indices…is that, strictly speaking, they measure internationalization and regionalization rather than globalization” (Reference Dreher, Gaston, Martens and Van BoxemDreher et al. 2010, 179, 181). In other words, they seem to agree with Held et al. on the importance of separating out intraregional and interregional international flows.

The KOF Index of Globalization, introduced in 2006 and produced by ETH Zurich, combines a wide range of metrics, going all the way back to 1970. It divides globalization into the spheres of economic, political, and social integration and uses indicators of each of these to build the index. These indicators are weighted based on principal-component analysis to ensure maximum variation, which has conceptual appeal but does result in weights that are hard for us, at least, to reconcile with our priors. For example, international transfers as a percent of GDP receives only a 0.4 percent weight, whereas membership in international organizations receives 7 percent. Even odder, probably, are the allocations of a 5 percent weight to McDonald’s restaurants and another 5 percent to Ikea stores, especially when juxtaposed against a 4 percent weight for all of merchandise trade.

In terms of types of measures rather than weights attached to them, the KOF index mixes together enablers of globalization (such as tariff rates and capital account restrictions) and actual levels of connectedness (such as trade and capital flows). More than half of its weight is allocated to indicators that we deem to reflect policy and technological enablers of globalization. Furthermore, some of the measures, for example, internet and television penetration, seem more like general indicators of economic development rather than of globalization. While internet and television connectivity can facilitate international information flows, data presented in Chapter 2 indicate that they are primarily used for domestic communication.

The Ernst & Young Globalization Index, last updated (as of this writing) in (2012), is somewhat closer to the DHL Global Connectedness Index. This index was designed by the Economist Intelligence Unit and is based primarily on their data. The weights of the main pillars are based on a survey of business leaders: 22 percent on trade, 21 percent on capital and finance, 21 percent on technology exchange and ideas, 19 percent on movement of people, and 17 percent on cultural integration. Note that four of these five pillars coincide at least roughly with those of the DHL Global Connectedness Index. However, subcomponents of the Ernst & Young Index adding up to 27 percent of the total are based on subjective measures – the Economist Intelligence Unit’s analyst ratings. In addition, this index covers only sixty countries.

Although Ernst & Young’s use of a business leader survey to set its weights has the advantage of focusing on the interests of its audience, it has some problems. First, none of the pillar weights is particularly distant from one-fifth. More importantly, however, the use of a survey can be problematic since even prominent business leaders are prone to believing in globaloney, as we discuss in Chapter 2.

The Maastricht Globalization Index, most recently published in 2014, takes a somewhat different approach. While higher values for most of the indexes covered here (including the DHL Global Connectedness Index) would generally be seen positively – at least by people who believe increased interconnectedness is a good thing – the MGI departs from that by including indicators on military spending and ecological footprints of exports and imports. This index is subdivided into five pillars: political, economic, social and cultural, technological, and environmental, each of which receives an equal weight. While allotting 20 percent of the total weight to the environmental footprint of imports and exports raises questions, the MGI generally seems built on defensible indicators, many of which also underpin our index.

Finally, the McKinsey Global Institute Connectedness Index (McK) also draws on many of the same indicators as the DHL Global Connectedness Index (and its initial release acknowledged having built upon our work) (Reference Manyika, Bughin, Lund, Nottebohm, Poulter, Jauch and RamaswamyManyika et al. 2014, 61). McK does look beyond depth, as reflected in the correlations described earlier in this section. However, rather than complementing depth with breadth, McK combines “flow intensity [depth] with each country’s share of the global total to offer a more accurate perspective on its significance in world flows” (Reference Manyika, Lund, Bughin, Woetzel, Stamenov and DhingraManyika et al. 2016, 56). Although the “significance” of a country’s international activities beyond its own borders is interesting, we view this as only indirectly related to a country’s actual level of globalization (shares in global flows themselves being a function of depth and country size). Nonetheless, rather than viewing this as a problem, McK argues in their methodological appendix that intensity measures “artificially boost small countries,” prompting the inclusion of countries’ shares in world flows to “correct” for this (Reference Manyika, Lund, Bughin, Woetzel, Stamenov and DhingraManyika et al. 2016, 125). In light of our earlier discussion of Reference Squalli and WilsonSqualli and Wilson (2011), upon which McK drew in constructing their index, we view this as arbitrary at best.

Changes in Globalization over Time

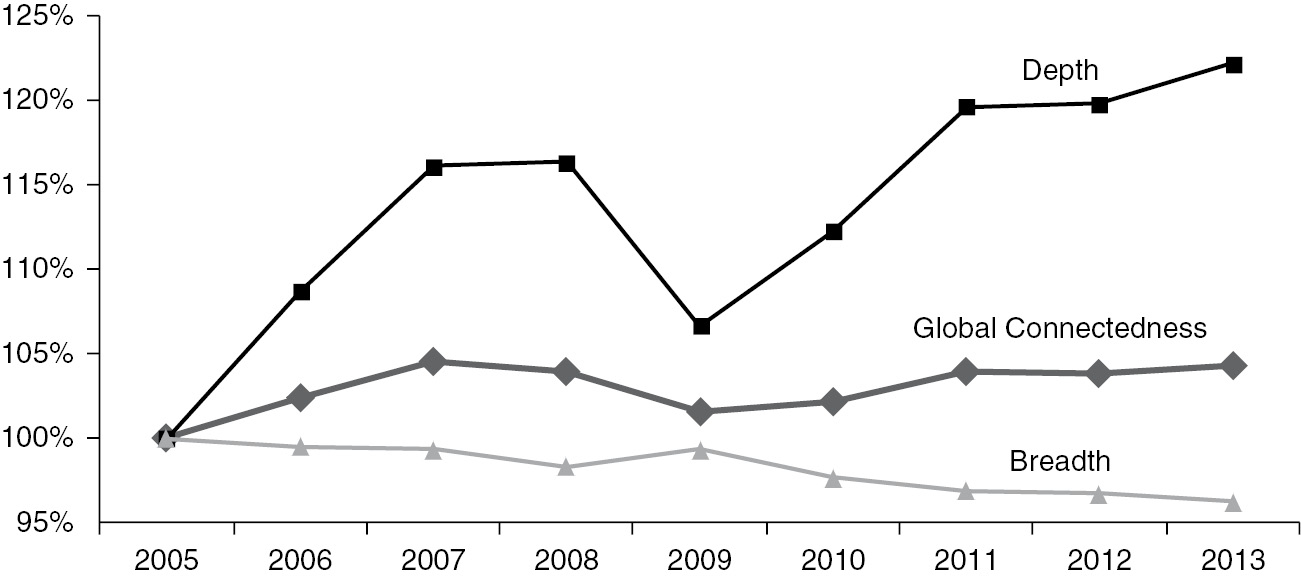

The discussion in the previous section should have highlighted the range of choices in constructing a globalization index – even if one only chooses to measure depth. To gain a sense of the comparative attractiveness of these indexes relative to each other as well as to the DHL Global Connectedness Index, it is useful to consider their recent evolution. Before the onset of the crisis in 2007, when globalization was unequivocally rising and the only question of interest was “by how much,” the differences between indexes were less striking. The DHL Global Connectedness Index 2014, like other indexes, shows that from 2005 to 2007, globalization increased (see Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Global Connectedness, Depth, and Breadth 2005–2013.

In 2008, however, the financial crisis provided an important checkpoint for globalization indexes. According to the DHL Global Connectedness Index, globalization dropped off in 2008, decreased significantly in 2009, and even by 2013, had not fully recovered to 2007 levels. In contrast, the other indexes reported only a slowing or stagnation around the financial crisis – not a drop-off. Figure 1.3 compares trends in the depth of globalization reported by the DHL Global Connectedness Index and globalization trends based on the other indexes. The KOF, Ernst & Young, and Maastricht indexes all focus on depth, but did not show any decline as a result of the 2008 global financial crisis: only KOF registered as much as a brief pause.17 (We exclude the McKinsey index from this section because that index has not released trend data.18)

Figure 1.3 Globalization Trend Comparison across Indexes, 2005–2013.

This difference is not due to differences in the schemes employed to aggregate data across countries. Global trends reported by the other indexes reflect simple averages across countries’ scores. However, given the tremendous variation across countries in terms of size and participation in international interactions, the DHL Global Connectedness Index (starting in its 2012 edition) adopts a system that permits the calculation of weighted averages at a global level as well as at intermediate levels of aggregation. To check that the differences between the DHL Global Connectedness Index and the other indexes are not driven by this focus on weighted versus simple averages, we recomputed our depth trends using simple averages (the dotted line in Figure 1.3). Even with this alternate averaging method, the DHL Global Connectedness Index remains the only index to register a significant drop in the wake of the crisis.

The crisis-era decline in globalization that the DHL Global Connectedness Index reports seems to fit better with contemporaneous accounts than the trend depicted by other indexes. The Economist’s February 2009 issue proclaimed that “the integration of the world economy is in retreat on almost every front,” and highlighted drop-offs in trade, capital, and people flows. The same article also noted a change in popular rhetoric about globalization, stating that “the economic meltdown has popularised a new term: deglobalisation” (Economist 2009). And former US deputy treasury secretary Roger C. Altman addressed increased roles of national governments in regulation and protectionism in his 2009 Foreign Affairs article entitled “Globalization in Retreat” (Reference Altman2009, 5). Jean Pisani-Ferry and Indhira Santos spoke of an “end (for now) of a rapid expansion of globalization” in a March 2009 article, pointing to public participation in the private sector, financial fragmentation, and increased tariffs (Reference Pisani-Ferry and Santos2009, 8).

Since the end of the crisis, we seem to have entered an age of ambiguity, in which perception of the trajectory of globalization has been uncertain at best and contradictory at worst. Thus, within one month in 2015, the Washington Post offered its readers the full range of possibilities. On August 30, 2015, it published a piece by Robert J. Samuelson (Reference SamuelsonSamuelson, 2015) called “Globalization at Warp Speed,” but less than a month later, on September 20, 2015, the Washington Post Editorial Board (Editorial Board, 2015) wrote a piece entitled “The End of Globalization?”

This ambiguity suggests a particular need for timely measures of globalization. If a globalization index is to be a useful tool for business practitioners and policymakers, new data must be available on a regular basis to inform decision making. The DHL Global Connectedness Index is released with an eleven-month lag since the end of the most recent year measured. By contrast, KOF is usually published with a twenty-eight-month lag, and the most recent editions of the McK, E&Y, and MGI indexes were published with twenty-seven-, twenty-four-, and sixteen-month lags respectively. In addition, we are actively engaged in efforts to improve on this lag where possible – particularly in measuring depth, which along several pillars can be quite volatile over time.19

Conclusion

The term “globalization” rose to prominence in the late 1990s and 2000s, and has taken on a wide variety of meanings. The definition by Held et al. has been particularly influential in the business and economics literature. Building on this definition, we propose depth (or intensity) and breadth (or extensity) as primary measures of globalization. We compare this methodology, embodied in the DHL Global Connectedness Index, with other globalization indexes.

Our empirical work on depth and breadth also suggests two adjustments to how globalization is defined. First, the globalization trends captured on the DHL Global Connectedness Index show that levels of globalization can both rise and fall. This suggests that definitions should emphasize not only forward movement but also allow for reversals. Second, empirical work on breadth shows that the majority of international interactions take place within rather than between major world regions. Excluding intraregional interactions, as Held et al.’s conception of extensity suggests, would result, in our view, in a severely incomplete view of international interactions.

The notions of depth and breadth we discuss in this chapter underlie the chapters that follow in Parts I and II of this book (even though the precise measures from the DHL Global Connectedness Index are often modified as necessary). Depth at the country level, over time, and from a company perspective are the foci of Chapters 2 through 4, which establish the law of semiglobalization, and breadth is the focus of Chapters 5 through 7, which cover the law of distance. Finally, depth and breadth are brought together in joint applications of the two laws in Chapters 8 through 11 in Part III.