1. Introduction

The authorship of On Liberty has been a cause of puzzlement since its first publication in 1859. In the famous dedication, John Stuart Mill declares that his deceased wife Harriet Taylor Mill ‘was the inspirer, and in part the author, of all that is best in my writings […]. Like all that I have written for many years, it [On Liberty] belongs as much to her as to me.’Footnote 1 The Autobiography adds further details to this picture: ‘After it [On Liberty] had been written as usual twice over, we kept it by us, bringing it out from time to time and going through it de novo, reading, weighing and criticizing every sentence. Its final revision was to have been a work of the winter of 1858–59 […].’Footnote 2 John Stuart Mill presents On Liberty as the joint product of two persons who discussed every sentence of the text.Footnote 3

So why did he decide to publish the book under his name only? Whatever his reasons might have been, do we have good reason to continue this practice of denying unequivocal co-authorship status to Harriet Taylor Mill? We call this normative question the On Liberty Authorship Puzzle. Footnote 4 The issue is no trifle. On Liberty is part of the philosophical canon. If Harriet Taylor Mill (hereafter HTM) should be credited as author next to John Stuart Mill (hereafter JSM), it would be the first time that a central text in the history of political philosophy would change authors after its publication.

The still prevalent answer to the authorship puzzle consists in (i) contesting that HTM's contribution was in fact as significant as JSM asserts and (ii) claiming that this justified JSM's decision to deny HTM unequivocal co-authorship status. We call this the conservative solution to the authorship puzzle. The evidence currently available does not contradict the conservative solution: apart from JSM's sweeping assertions, we do not have any detailed record about who is responsible for particular ideas or specific formulations in On Liberty. Furthermore, concerning the intellectual capacities of his wife, the reliability of JSM's testimony was already questioned by Mill's contemporaries. His friend and biographer Alexander Bain even refers to Mill's assessment of her capacities as ‘hallucinations’.Footnote 5 The extent and nature of her contribution has ever since been cast into doubt.

The first to demur regarding the conservative solution was Hayek. If JSM is generally considered to be a highly reliable source, what reason is there to doubt his testimony on HTM specifically?Footnote 6 Hayek himself reserves judgment on HTM's capacities but clashes with the conservative solution in confirming her strong influence on JSM's thinking.Footnote 7 Since the 1970s scholars have increasingly challenged the conservative solution as the product of essentially sexist assumptions in combination with an inappropriate understanding of how authorship should be conceptualised.Footnote 8 These scholars give support to what may be called the critical solution to the authorship puzzle: (i) HTM's contribution was at least as significant as JSM asserts, and (ii) he should not have denied her authorship. The critical solution presses us to reconsider our understanding of the ways a bona fide author has to contribute to a text (other types of input than writing should count as contribution), but it also confronts us with a troubling conclusion regarding JSM. Does he, still the most notable male feminist in the history of philosophy, play a part in the problematic practice of ‘downgrading, making invisible, and concealing the position of women in the field of philosophy’?Footnote 9 We call this the downgrading charge against Mill.

The critical solution also has its problems, though. It is mainly grounded in JSM's testimony, which unfortunately is not unambiguous. Dale Miller reminds us that JSM does not mention HTM as co-author of On Liberty in his personal bibliography, and in letters ‘he refers to the essay as his and to himself as the one writing it’.Footnote 10 On 5 October 1857 JSM writes to Theodor Gomperz: ‘I have nearly finished an Essay on “Liberty” which I hope to publish next winter.’Footnote 11 And on 4 December 1858 he lets Gomperz know that he lost Harriet, his ‘perfect friend, companion, guide, teacher’ and that his ‘small volume on Liberty will be published early this winter’, without addressing issues of joint authorship.Footnote 12 To HTM he writes on 15 January 1855 that he ‘came back to an idea we have talked about, & thought that the best thing to write & publish at present would be a volume on Liberty’.Footnote 13 If Harriet agrees ‘I will try to write & publish it in 1856 if my health permits as I hope it will.’Footnote 14 These letters and the bibliography seem to suggest that Mill was truly convinced that he is the sole author of On Liberty, and indicate that his sole authorship may always have been the Mills’ joint plan. Even though we agree with Jacobs’ heuristic for authorship attribution, namely that ‘Without substantial evidence to the contrary, it seems reasonable to believe that work is collaborative if participants say it is’, it unfortunately is not entirely clear what the participants do say in this case.Footnote 15

After more than 150 years of debate the picture is therefore still inconclusive. In this article, we present a new approach which promises progress on two fronts. The largest part of our work consists in applying stylometric methods to On Liberty. Briefly, stylometry extracts the writing style of a person from his or her texts and then compares this ‘stylome’ to the stylome of texts the author of which is yet to be identified. Stylometric analyses depend on a number of potentially controversial premises, as explained in greater detail below. According to the models we present, one can say with some degree of confidence that JSM did not write On Liberty all by himself and that HTM played a part in putting parts of the text into words. Even though we do not have available the gold standard evidence for On Liberty, such as pencil marks and handwritten comments, which Stillinger could use in his ‘Who wrote J. S. Mill's Autobiography?’, the statistical models on which our stylometric ascriptions are based are decidedly better than intelligent guesses.Footnote 16 By exploiting this hitherto unused source of information, we hope to put a gridlocked debate in motion. Although we consider our results as preliminary, we are convinced that stylometric methods have the potential to bring us closer to a satisfying solution of the authorship puzzle.

In addition to this new kind of empirical evidence, we offer considerations on conditions for authorship attribution, an issue that has remained underdeveloped in the debate so far. We will draw on relatively uncontroversial principles for authorship ascription found in guidelines for good scientific practice.Footnote 17 Notwithstanding the stylometric case for HTM's contribution we present, there might have been normatively acceptable reasons for JSM to publish the book under his name only. In that sense, both the conservative and the critical solution would be mistaken.

We proceed as follows. In the second section, we describe the periods of cooperation between JSM and HTM, outline our position on attribution of authorship and sketch the objective and scope of our analysis. Sections 3–5 present the evidence on HTM's contribution: the third section describes stylometry and how it helps to distinguish who of several potential ‘scribes’ has actually written a passage.Footnote 18 In the fourth section, we present the first results of our project with a simple cluster analysis on our entire corpus. The fifth section presents the second set of results, using the ‘rolling classify’ function of the software package Stylo, which detects the most likely author of specific sections of On Liberty. The sixth section reconsiders the authorship puzzle against the backdrop of our results and argues that the downgrading charge against JSM might well be mistaken.Footnote 19

2. Cooperation and authorship

Because our stylometric methods compare On Liberty with other paradigmatic texts of the potential authors, it is of crucial importance first to understand clearly which texts would be suitable candidates for comparison.Footnote 20

Ideal conditions for stylometric analyses are the following: (i) Same genre: The stylome is influenced by the genre; thus, one gets better results if one compares texts that belong to the same genre. (ii) Same period: The stylome might change over time; thus, it is better to compare texts from the same period. (iii) Enough text: The more text of any author there is, the more accurately the stylome may be extracted. (iv) Same amount of text: If there is much more text of one author than of the other, the models might get biased; thus, it is better to have a similar amount of texts from all potential authors. (v) Correct labels: The texts one uses in order to build the stylometric model must be correctly labelled initially.

Conditions are less than ideal in all respects when it comes to the cooperation of JSM and HTM. The authorship of many texts in the relevant corpus is controversial, the corpus of HTM is very thin in comparison to JSM's, and one cannot exclude the possibility that the analyses are affected by genre and period effects. For instance, it is plausible to believe that before the first meeting of JSM and HTM in 1830 and after HTM's death in 1858, their respective individual writing styles would have been different from their styles during their phase of cooperation. Even though including texts from these periods would in principle allow for a more precise stylistic analysis due to the larger quantity of text, this potential change in style would provide a source of error. We therefore restrict our analysis to the phase from 1831 to 1858.

In the years 1831 till 1849, the year of the death of HTM's first husband John Taylor, we see a very productive period for HTM, a large number of newspaper articles co-written by HTM and JSM, and two major books published under JSM's name: the System of Logic in 1843 and the Principles of Political Economy in 1848. The next phase lasts from 1850, the year of their marriage, till 1858, the death of HTM. There are few texts published under JSM's name in this phase (the main texts being ‘Whewell on Moral Philosophy’ and the reviews of Grote's History of Greece). The fourth phase, the years till 1873, the year of JSM's death, sees the publication of many of his most famous pieces. Of particular interest here are On Liberty (1859), Utilitarianism and Considerations on Representative Government (both 1861), Subjection of Women (1869) and the posthumous Autobiography (1873).

The articles published under both names provide the evidence for paradigmatic texts of co-authorship of HTM and JSM. These are mostly newspaper articles. This is somewhat unfortunate because of a presumed genre effect. Newspaper articles differ from academic writings, hence newspaper articles do not represent the best conceivable evidence on a potential joint writing style to be found in the more academic On Liberty. But they are (almost) all we have available.

Of course, we do not take all title pages at face value to assign authorship in our corpus. In some cases, we already have strong evidence that the title page does not reflect actual authorship. The Principles of Political Economy provide a case in point. On some interpretations, all of the chapter entitled ‘On the Probable Futurity of the Labouring Classes’ is assigned to HTM.Footnote 21 However, as highlighted by Miller, JSM states clearly that, though HTM might have inspired him to write it, he actually wrote it:

In the first draft of the book, that chapter did not exist. She pointed out the need of such a chapter, and the extreme imperfection of the book without it: she was the cause of my writing it; and the more general part of the chapter, the statement and discussion of the two opposite theories respecting the proper condition of the labouring classes, was wholly an exposition of her thoughts, often in words taken from her own lips.Footnote 22

The authorship of the rest of the Principles is also somewhat controversial. Though it might seem natural to assign all of it to JSM – again, as Miller highlights, though Mill does mention the Principles as co-authored in his Bibliography (‘joint production with my wife’Footnote 23) the private dedications inserted into some copies given to friends do not mention a co-authorship of HTM at all – we decided to follow the interpretation of Jacobs throughout. That is, we divide the Principles into two parts and attribute Chapter 7 of Book IV to HTM and the rest to HTM and JSM jointly. Though this assignment can certainly be challenged, it is only one of a number of choices we had to make, especially on technical issues, which all might be considered more or less disputable. Instead of trying always to find the ‘best’ solution to each of these issues – a certainly worthwhile and challenging endeavour, but somewhat outside our area of expertise – we considered it more viable to present one well worked-out perspective on the joint production of JSM and HTM, that of Jacobs, as a starting point.Footnote 24 It remains to be seen in the future whether other perspectives will yield better results.Footnote 25

For instance, starting from a different perspective than Jacobs, it could be argued that we should include even more texts as co-authored by HTM&JSM in our corpus. After all, JSM himself claims that in a ‘wide sense’, literally all texts written in the period 1831–58 were the ‘joint product of both’, even when the title page says differently. He justifies this claim with a perfect ‘unity of mind’ between the two. According to him, he discussed with HTM ‘all subjects of intellectual or moral interest […] in daily life.’Footnote 26 Would perfect unity of mind be sufficient to count HTM as co-author of all works written in this period, including On Liberty?Footnote 27 We think this would be a little bit too radical. This approach would go much further than even what the adherents of the critical solution endorse, who emphasise that HTM made a genuine yet somewhat hidden contribution to many texts. They claim that HTM did not merely agree with everything JSM said or wrote – perfect unity of mind would not entail more than that – but, in addition, has had a detectable impact on what JSM said or published under his name.

Contemporary research integrity guidelines reflect this plausible view, common ground in the debate, that a substantial and identifiable contribution to a text is required for authorship. Individuals who did not contribute to a publication must not be listed as co-authors. This is intended to exclude so-called guest/gift/honorific and (of course) forged authorship.Footnote 28 The contribution required by this contribution condition, as we call it, may consist in different things, such as taking part in the conception or design of a work, drafting or substantially revising it, but merely agreeing with a text is not enough.Footnote 29 Hence unity of mind alone would not be a contribution in the required sense, and HTM should not be counted as co-author of On Liberty on this basis.

In many cases, however, Mill maintains that HTM did contribute to the production of specific texts. Unfortunately, neither JSM nor HTM identified how she did contribute with sufficient precision. As mentioned above, the conservative solution doubts that HTM's part was substantial enough to satisfy the contribution condition. It is controversial whether less tangible contributions such as the verbal provision of ideas, feedback on text or thoughts, background knowledge or a general outlook would at all satisfy this condition,Footnote 30 but it should not be controversial that the writing of actual text does satisfy it. If one can identify such traces of an individual scribe, one normally has strong evidence for assuming that the contribution condition is met by this individual. This is what we are attempting to achieve.Footnote 31

A second fundamental principle of authorship attribution in collaborative work may be called the approval condition. The approval condition is normative. It emphasises that authorship entails co-responsibility for the content of the publication as a whole. In a joint publication, each author can be held accountable for the contributions of other authors. Thus, each author must know, understand and approve – to a degree deemed sufficient by the co-authors – what is being published in his or her name. Anyone listed as co-author is within reasonable bounds answerable for the content of the publication as a whole.Footnote 32 Certainly, each person mentioned as author should explicitly approve of the final version and could veto being listed as author.

Jacobs applies something like the approval condition with regard to ‘Enfranchisement of Women’. She claims JSM assigned authorship to HTM although they ‘clearly worked together on drafts of ideas that would serve as the core of the article’. According to Jacobs, the reason was that the ‘article contained ideas with which John did not completely agree’.Footnote 33 We similarly believe that, in the case of On Liberty, we have to take seriously the possibility that it was HTM who did satisfy the contribution condition, but not the approval condition.

3. Stylometry

Our present aim is to determine how much of On Liberty has been written by one of the three scribes (JSM, HTM, HTM&JSM). The general strategy is first to detect a particular style for each by analysing texts clearly attributable to them, leaving On Liberty out of the analysis. Once this is done, we test which of the three is the most plausible author of On Liberty. Later on, we will also determine which sections are likely to have been written by which scribe.

The discipline of stylometry investigates the personal style of an author by applying statistical analyses to his or her texts. The major empirical insight of stylometry, which we take as given, is that authors have specific writing styles, called ‘stylomes’ which, maybe surprisingly, are identifiable by the personal frequency of so-called ‘function words‘ such as ‘and’, ‘or’, ‘the’, ‘an’ etc.Footnote 34 There is, in other words, a frequency distribution over function words that is characteristic of a particular author (at a particular time, for a particular genre, etc.). Though it may be possible for trained readers to detect very characteristic phrases of specific authors and thus to detect whether, say, it was Kant rather than Wittgenstein who wrote a particular text just by looking at the syntactical information, without even processing the semantics, it has been shown that this traditional ‘close-reading’ technique is much less reliable than modern stylometric techniques.Footnote 35 In so-called ‘distant-reading’,Footnote 36 computers, not humans, are doing the ‘reading’. They are able to syntactically analyse within seconds a large number of texts, indeed entire corpora of works, and hence can reveal complex patterns human readers with limited cognitive and temporal capacities could not possibly pick up. Computers process texts faster and are (at least in some regards) less biased than humans.

The stylome of an author thus extracted is not normally of independent interest, as it fundamentally only consists of a long list of ‘most frequent words’ (MFWs) in regular use.Footnote 37 But, as with On Liberty, it is often of considerable interest to determine whether a particular person has actually authored a piece of writing attributed (or not) to him or her. The stylome, if reliably established, may contribute to this.Footnote 38 Famous examples of results of such authorship attribution include the long-standing question of what Shakespeare wrote and the recent case of J. K. Rowling, the author of the Harry Potter novels, who turned out to be the author of some crime novels using the pseudonym ‘Robert Galbraith’.Footnote 39

Without credible ex-post confirmation by the actual author or further strictly historical evidence such as reliable eyewitnesses, manuscripts with identifiable handwriting, unambiguous notebook entries etc. – all of which may be disputed, too – authorship attribution using stylometric techniques provides less than full proof. At the moment, there is no established procedure for determining precisely how conclusive any particular analysis is, as there is no established procedure on how authorship attribution must proceed.Footnote 40 As mentioned, any stylometric investigation also requires a large number of potentially controversial parameter-setting decisions which might have a major impact on the results. All such choices should at least be made explicit and justified, and there are often good reasons to decide one way or the other. It should be noted, however, that results appealing to distant-reading techniques always ought to be considered as one piece in a larger puzzle only. Ideally, they are supplemented by further kinds of evidence, if available. Yet it is also important to realise that there are parts of the puzzle that only stylometry may contribute. Because stylometry provides an entirely novel kind of evidence, it holds the promise of helping to resolve some traditional questions on which no further conventional evidence may be expected to be forthcoming.

4. A cluster analysis of On Liberty with Stylo

For our analysis, we used the open-source library Stylo.Footnote 41 Stylo is the state-of-the-art analysis tool for stylometry. It is a library for R, a free and well-established programming language for statistical computing for which supplementary packages are developed, serving specific interests. It is continuously being updated and improved by the Computational Stylistic Group.Footnote 42 Stylo offers several settings when analysing corpora. For our project, so-called ‘cluster analysis’ and ‘rolling classify analysis’ are the two fundamental features.

As a first illustration, consider Figure 1 below, displaying a cluster analysis, which groups texts together by their stylometric distance. Its inputs are individual texts in their entirety, not sections of texts. The texts first need to be prepared and formatted (cf. the online appendix). As described in section 2, of some of these texts, we take the authorship as given, these begin with ‘htm’, ‘jsm’, or ‘htm&jsm’, as the case may be. We do not attribute an author to the text of interest for us, On Liberty, hence it begins with ‘test’. Stylo then computes the MFWs for each of the texts, and groups the texts together, using a distance measure (without taking into account the file names).Footnote 43 The overall cluster analysis runs on our entire corpus, consisting of 273 texts. It's impossible to display the entire diagram, so we may only show an illustrative section of a slightly reduced yet representative corpus.Footnote 44

Figure 1. Cluster analysis.

The main result is that On Liberty clusters most closely with Considerations on Representative Government. This means that there is no text in the entire corpus that is more similar in its stylome to On Liberty than Considerations. The next closest texts are The Subjection of Women and Utilitarianism, and then follows, perhaps surprisingly, ‘Enfranchisement of Women’. Thus, according to the section of the graph visualised, it looks like On Liberty was written by JSM. Furthermore, apparently so was ‘Enfranchisement of Women’, as this text too clusters very closely with other texts by him, rather than closely to texts written by HTM.

We also note that the co-authored newspaper writings closely cluster together. This indicates that the cluster analysis reliably identifies the different authors – those texts which were co-authored (according to the title page) do have a distinct stylome. However, it is impossible to disentangle this signal of co-authorship from a potential genre effect.Footnote 45

5. Classify and rolling classify

The cluster analysis clearly suggests that On Liberty is more like texts by JSM than those by HTM or HTM&JSM. This provides some evidence that HTM did not substantially contribute to it. However, the cluster analysis treats the entire text as one big heap of words, ignoring any internal structure. If, for instance, HTM had written some paragraphs all by herself, using a very characteristic stylome, but those paragraphs were so short that they made up only a small proportion of the overall text, the cluster analysis would not show this, given that it is designed to show only similarities among texts as a whole. The contribution, even if real, would be so minor in terms of how it changes the word frequencies of the overall text that it could not push the text over to the co-authored items or the texts written by HTM on her own. This is an inherent limitation of cluster analyses, which are not designed to look inside the texts.

For this reason, the second analysis we want to perform is a ‘rolling classify’ analysis.Footnote 46 Such an analysis divides a text into overlapping sections of a given size and then computes the most plausible author of each section. A rolling classify analysis thus allows us to detect authorship signals that appear only in certain parts of the text. This is the mechanism most suitable to detect the exact location at which individual scribes have contributed in terms of formulating the text.

Before we get there, however, we need to describe how the classify mechanism works. The ‘mechanism’ actually is a machine learning algorithm which determines the author of any text from a given set of potential authors by testing and refining models predicting authorship. Intuitively, we are trying to find the algorithm most reliable in building a model to detect who authored which text. Once we have determined this, we will use the model to classify the individual sections of On Liberty. Stylo offers several such algorithms, two widely used ones of which are the support vector machine (SVM) and the nearest-shrunken centroid (NSC).Footnote 47 We decided to use both so as to be able to compare their results.

Finding the most appropriate settings for the models tested by the algorithms was the most challenging aspect of this project, as there are many interacting problems to address, each of which generates a huge amount of data. The settings are of crucial importance as they radically change the results. Abstractly speaking, this process, called ‘cross-validation’, consists of two steps, training and testing. The training works as follows. We are assuming we know the authorship of all texts, except On Liberty, which we remove from the corpus entirely. We are now ‘training’ the models using the algorithms to reliably detect who authored which of all the other texts. For this, 10% (or 20%) of the texts of each author are removed from the corpus. These are the ‘test set’; the remaining texts constitute the ‘training set’. The algorithms then use a ‘black box’ deep-learning mechanism on the training set to improve how well the models detect the respective authors. This training procedure gets repeated 100 times, with random divisions of test and training set.

The resulting models are then checked for their quality using the test set. This cross-validation serves to test the ‘accuracy’ of the model. If a particular setting of the model used by a particular algorithm yields a model with 70% accuracy, for instance, that means 70% of the texts in the test set have been identified correctly by that model.Footnote 48

Clearly, such a procedure raises a number of issues. We don't understand intuitively how the models identify scribes. Even if we understand the underlying theoretical idea, we may only see how accurately they do so. This inherent limitation of machine learning might be intellectually disappointing. More problematically, the accuracy in this sense does not seem to be a valid criterion to decide between models. For example, if a 70% accuracy on average is derived from a 95% accuracy for JSM, but only a 50% accuracy for HTM (i.e. not better than chance) and an accuracy of 75% for HTM&JSM, this is of little help for determining the potential contribution of HTM. In fact, we have reason to believe this exact problem could arise in our case, as the corpus for JSM is much larger than are the corpora for HTM and HTM&JSM. Because of this, unclear cases are more likely to be correctly classified as JSM even by a chance process, because the vast majority of texts will actually be his. This is the so-called ‘class imbalance’ problem. Training the algorithm on an imbalanced set so as to achieve high accuracy does not help us addressing our research question.

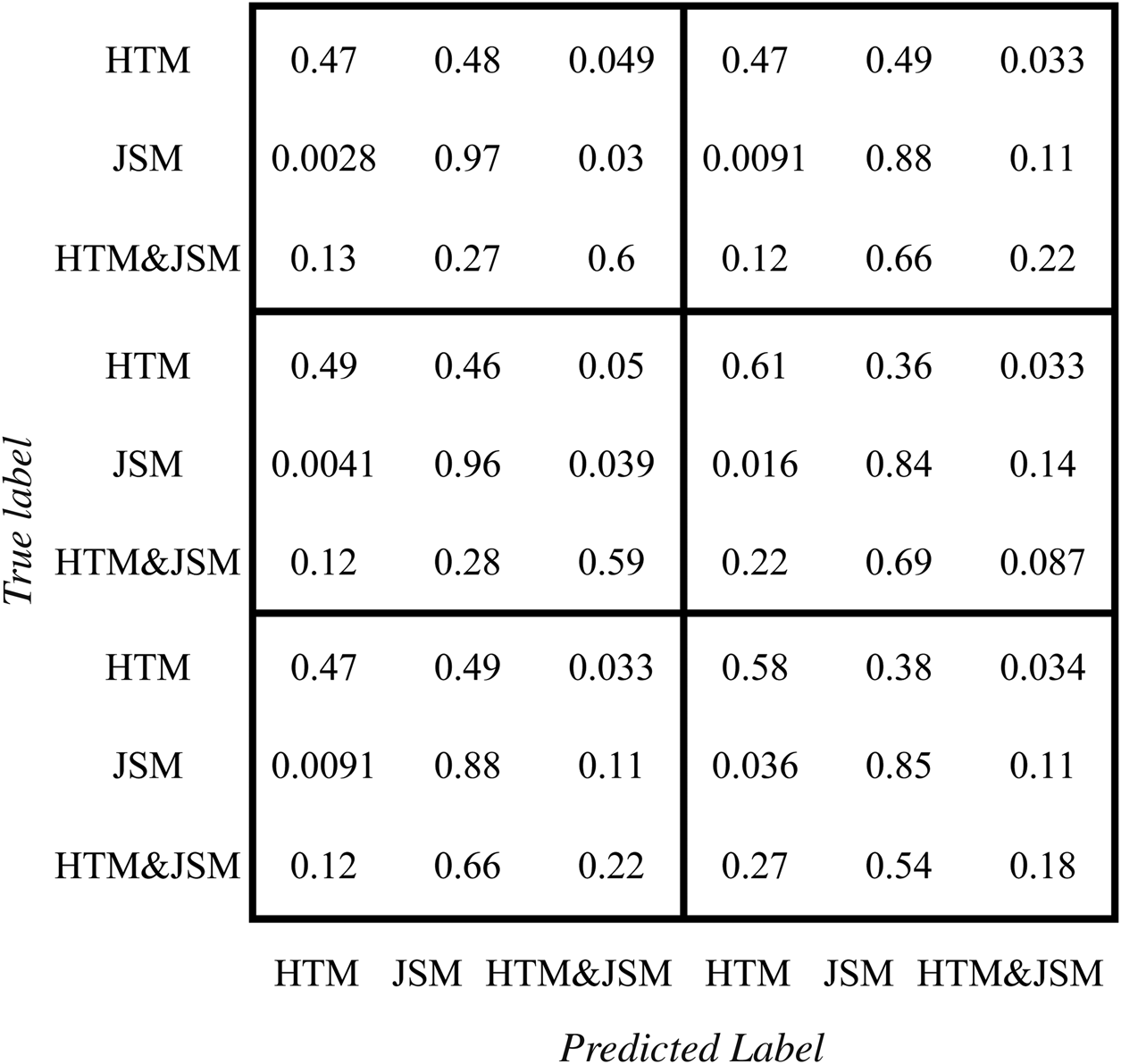

The machine learning literature provides different approaches to this problem. We chose to follow the procedure described by Efstathios Stamatatos (details are to be found in the online appendix).Footnote 49 We are going beyond this approach in one important way, however, because we are not focusing on accuracy alone, but also consider ‘precision’ and ‘recall’.Footnote 50 We have inserted the relevant numbers in six confusion matrices (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Confusion matrices A–F, our analyses.

A confusion matrix displays how well any particular model works, for a particular set of parameters. Most applications are binary classifications, and in such a case, a confusion matrix would contain four cells only. For instance, if some texts should be assigned to author A or author B, who are known to be the only two possible authors, there are four logically possible outcomes – two true and two false cells. In our case, the confusion matrices have nine cells. They show how many of the texts actually written by JSM (in the respective second lines, the true label is ‘jsm’) the model correctly identifies or ‘predicts’ as written by him (second line and second column, the predicted label is also ‘jsm’), incorrectly as not having been written by him (second line and first or third column), and, of those actually not written by him (but by HTM, first line, or HTM&JSM, third line), as correctly written by HTM or HTM&JSM, as the case may be, or, incorrectly, as written by him.Footnote 51

The predictive models with a total number of 8800 settings we tested all differ in the values they yield. At the end, we had to make a decision on which model to use. This decision necessarily involves a trade-off: some models score more highly in some cells, others in others. Because in practice there is no single predictive model that is better than all others in all cells, there is no single ‘right’ solution on which model and which settings to use, and no ‘right’ answer to the question of which of these cells is more important than the others.

The machine learning literature offers a number of common measures giving different weights to the cells and their combination, that is, giving different weights to precision and recall, in order to achieve a sensible compromise. The ideal scenario would of course be a model that has perfect precision and perfect recall, but perfect precision and perfect recall are not achievable in our case.Footnote 52

We decided to go with what to us appeared the most neutral measure, the so-called ‘F1-measure’, standard in the machine learning literature. It does not simply average precision and recall, it strikes a balance by measuring their harmonic mean.Footnote 53 Intuitively, the harmonic mean gives less weight to the more extreme values recorded than the arithmetic mean (colloquially known as average). The idea is that both precision and recall are important, and that a very good value for one of the two should only partially compensate a terrible value for the other: We would rather have a model that scores alright on both objectives than one that scores phenomenally well on the one but terribly on the other.Footnote 54 The F1-score is computed for each line and then macro-averaged.Footnote 55

We optimised the F1 value for several settings for our two algorithms. In the authorship attribution literature, it is common practice to display only one or very few different final results, but we thought that, in order to obtain a complete picture, it would be more helpful to be able to compare several different algorithms. Our reasoning on which settings to use was as follows.

Clearly, we would have to include both SVM and NSC, as these are the most widely used algorithms, and we wanted to see whether their results confirm or contradict each other. Our impression was that SVM is generally deemed more reliable than NSC, so we used four different SVM settings and two different NSC settings. Those settings which yield the best F1 value across the board, for both SVM and NSC, needed to be included.Footnote 56 We also wanted to detect the effect of our sampling procedure and hence included the SVM and NSC settings with the highest F1-score using the sampling. Even though the sampling should control for the class imbalance problem, we were worried that because of the low number of co-authored HTM&JSM pieces and the presumed genre effect, giving equal weight to the line with the co-authored items might distort the overall results. Hence we also included the two best SVM analyses that only consider the lines for JSM and HTM, one without sampling, one with it. These would be somewhat less reliable in detecting joint authorship of course, but more reliable in detecting each of the other authors. The remaining trade-off between HTM and JSM we decided to resolve using the harmonic mean rather than the arithmetic mean, as all algorithms tended to perform significantly better on detecting JSM.

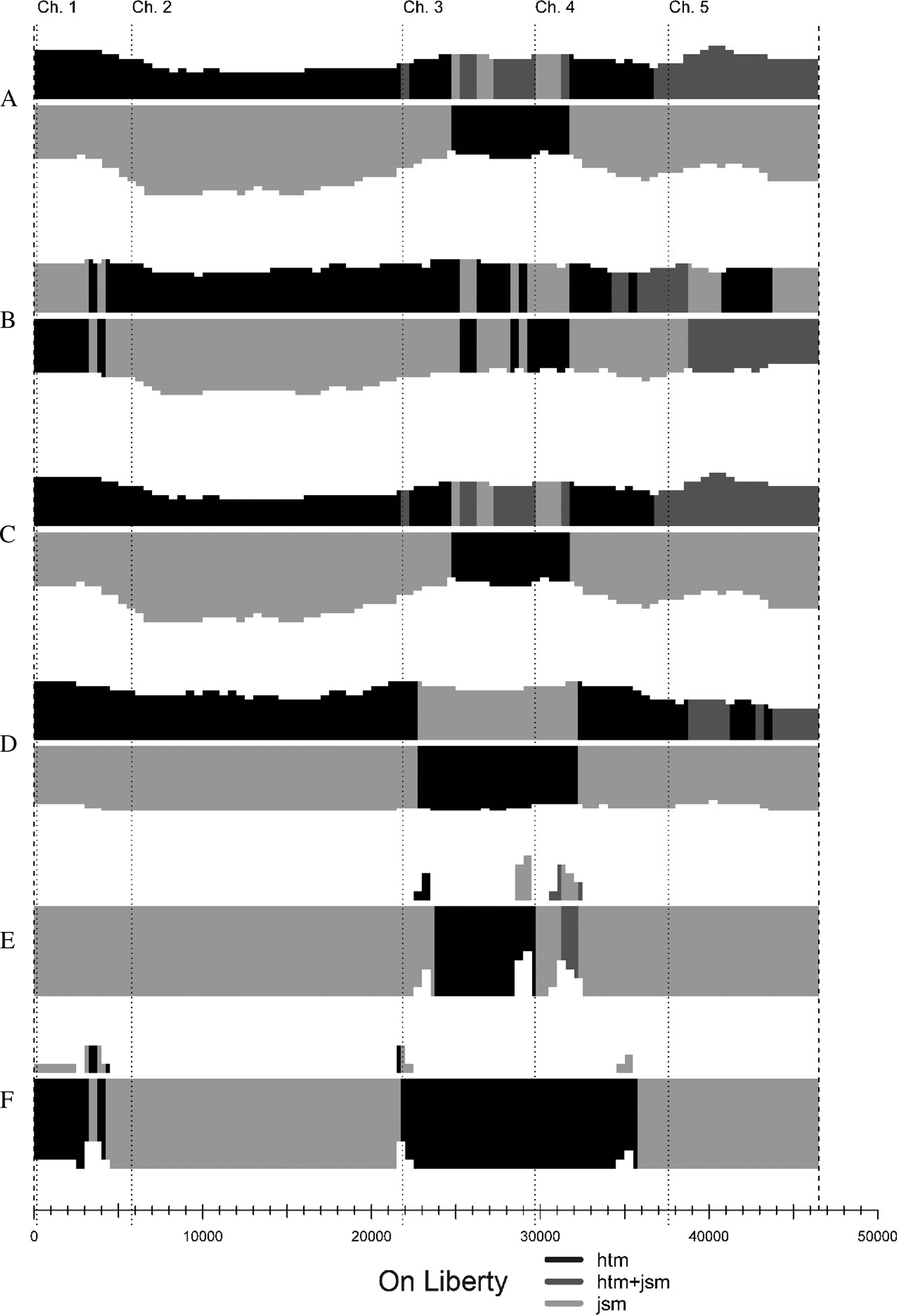

Consider Figure 3. Its six diagrams display the text of On Liberty, and the dotted lines mark the chapters.Footnote 57 The lower half of each diagram displays the most probable author of the relevant section, the upper half the second most probable (HTM is in black, JSM in light grey, HTM&JSM are in dark grey). The longer the lines, the higher the level of certainty of the classification. The two lower diagrams, using the NSC algorithm, look somewhat different from the top four, using the SVM algorithm, but the basic idea is the same.Footnote 58

Figure 3. Rolling Classify Analyses A–F (for settings, see footnote 58).

6. Results and implications for the authorship puzzle

Let's first note the remarkable result that HTM is the most probable scribe of some sections of On Liberty on all analyses. In other words, it is more likely that HTM has written these passages than that JSM has written them (given our corpus and further assumptions). In fact, all analyses converge in judging that HTM and not JSM most probably wrote some parts of chapter 3. This signal is rather weak on diagram B, but very strong on all others. In the top three diagrams, we also see a clear signal of co-writing in chapter 5, and co-writing is indeed most probable for almost all of chapter 5 on diagram B. Two diagrams (A and C) also give HTM&JSM as second-most likely author of large parts of chapter 3 when HTM is the most likely author. For JSM, the clearest result is his exclusive authorship of chapter 2. Chapter 1 is not as clear, as diagrams B and F assign it to HTM, and even in diagrams A, C, and D he is only a little bit more likely to be the author than HTM.

In assessing these diagrams, we should also take into account the values in the corresponding confusion matrices. The first matrix shows that the best setting of the SVM algorithm is very good at detecting JSM, but not nearly as good at detecting HTM. However, it also shows that almost all of the texts actually written by HTM and not assigned to her are assigned to JSM, rather than to both. So in diagram A, this model implies that some of the sections assigned to JSM have probably been written by HTM. The same is true for diagrams B and C, and, to a somewhat lesser extent, diagram F. In the first diagram, JSM also gets almost 30% of the texts written by both of them assigned to him. So, in diagram A, the contribution of JSM to On Liberty is probably overestimated. Similarly in diagrams B and D.

In other words: our models generally are very good indeed at detecting JSM, but not quite as good at detecting HTM or HTM&JSM. Thus we can say with a high degree of confidence which parts have not been written by JSM but by the other potential scribes, HTM or HTM&JSM, though it is harder to say which one of the two it was. As both involve HTM, however, we can say with a high degree of confidence that a lot of On Liberty has not been written by JSM alone. This is the main result of our stylometric analysis.Footnote 59

So what is the upshot for the authorship puzzle? Since its beginning in the nineteenth century, one feature of the debate has been its strong focus on the credibility of JSM's statements.Footnote 60 The ‘evidence’ presented by the sceptics regarding HTM's role consisted mainly in derogatory assessments of her as a person and thinker; frequently this assessment bordered on the defamatory. However, if our analysis approaches the truth, Mill's remark that ‘it is of little consequence in respect to the question of originality which of two persons [who have their thoughts and speculations completely in common] holds the pen’Footnote 61 should not be read as implying that HTM had no hand in formulating On Liberty. She was most likely deeply involved in putting central sections of On Liberty into words. According to our analysis, her part in writing was undoubtedly sufficient to fulfil the contribution condition for co-authorship status. If so, the conservative solution to the authorship puzzle has to be rejected.

Though we consider this to be a heartening finding for the feminist cause, it still leaves JSM fully exposed to the downgrading charge. In The Voice of Harriet Taylor Mill, Jacobs wonders why only JSM's name appears on the book's cover.Footnote 62 She offers two possible explanations which would partially exonerate Mill. First, ‘a book by J.S. Mill would receive a fairer hearing than one by John and Harriet Mill’, second, JSM may have hesitated ‘to place Harriet's name on a text he feared would be seen as “infidel book”’.Footnote 63 She continues that ‘John may have wanted paternalistically to shield her name from potentially intense criticism.' If we understand Jacobs correctly, she remains somewhat critical of JSM's decision: neither of the reasons given were actually sufficiently weighty to justify the absence of HTM's name on the title page, even though JSM might honestly have thought so.

This might be jumping to conclusions, though. In the second section, we introduced the approval condition of authorship: people must not be named as authors of a publication if they do not approve of being so named. We think that contribution and approval are individually necessary and jointly sufficient for legitimate ascription of authorship. Applying the approval condition to the case at hand, one might wonder whether JSM withheld co-authorship status not because HTM did not contribute, but because she did not approve of On Liberty, exonerating Mill completely.

The approval condition has a cognitive dimension (does a person believe that the claims in a text are acceptable?)Footnote 64 as well as a volitional dimension (is a person prepared to advocate the claims in a text in public?). Did HTM fully approve of the content of On Liberty, that is, did she approve cognitively? Let us examine different phases of their cooperation and different hypothetical scenarios. One can state with certainty that HTM did not approve of On Liberty while she was well enough to be convinced that she would partake in the manuscript's reworking. In his dedication, Mill writes that the book did not have the ‘inestimable advantage of her revision’ and that important portions had ‘been reserved for a more careful re-examination’.Footnote 65 We thus know that HTM did not approve of the later published text of On Liberty at that time. The same is true, of course, of JSM. Since he, too, was convinced that their final revision would make the text better and since it is a requirement of practical reason to prefer the better to the worse, JSM did not approve the final version at that stage. The interesting issue is the phase after it had become clear that there would be no joint revision of the text.

Let's consider two scenarios. In the first scenario, HTM expressed a last ‘deathbed wish’ concerning On Liberty. If her wish was to be mentioned on the title page, it seems inconceivable that JSM would have ignored the expressed wish of his dying wife, so we can confidently rule out this possibility. If the deathbed wish was not to be mentioned on the title page, Mill did nothing wrong in any case. This scenario would clear JSM of the downgrading charge and cohere with today's publication and citation practices.

In the second, less hypothetical, scenario, HTM did not express a deathbed wish regarding On Liberty. Because we know that HTM and JSM were convinced they were able to produce an even better book, we now have to ask whether HTM would have approved of being mentioned as future co-author of an as yet unfinished book which, as shown, did not fully satisfy her standards. This involves the second, volitional, dimension of the approval condition. Should we assume that HTM would have approved of figuring posthumously as an author of On Liberty, given its imperfections?

In order to answer this rather knotty question, further aspects have to be considered. The volitional aspect of the approval condition is grounded in respect for a person's privacy and liberty: people should have a reasonable degree of control over which of their convictions they want to share with whom and under which circumstances. It is wrong to restrain a person's right to express their views if they want to see them expressed, but it is also wrong to reveal a person's views if they don't want them to be revealed. Because of the volitional aspect, it is conceivable that a contributor fully approves of the content of a text yet does not approve of figuring as its author. Jacobs's and Allen's considerations would indicate that JSM thought HTM would not have approved of On Liberty for this reason.

The volitional aspect of the approval condition gives some leeway for providing potentially misleading authorship information. The pro tanto duty to be truthful about the authorship of a publication may plausibly be outweighed by unfavourable circumstances, such as a repressive public or state power. Within certain bounds, we assume that strategic deception of others is permissible in unfree societies. If such justifying conditions cease to prevail, though, the duty to be truthful regarding authorship becomes more binding again.

As a result, even if the considerations noted by Jacobs and Allen might have justified the provision of misleading authorship information in bigoted and sexist Victorian times, today they would give no reason to deny HTM the unequivocal status of being ‘the co-author of this classic’.Footnote 66 First, it is very unlikely that On Liberty would receive a less fair hearing today if HTM's name were to appear on the title page – quite the contrary. Second, On Liberty did not actually make a name for being an ‘infidel book’, and it certainly would not be considered thus today. So even if JSM was pursuing a legitimate objective in protecting the good name of his wife, assuming her disapproval for volitional reasons, today there is no need to maintain this protective attitude – again, quite the contrary, as proponents of the critical solution emphasise: HTM now needs to be protected from an undeservedly unfavourable reputation. The circumstances having changed, JSM's legitimate concerns now pull in the opposite direction.

7. Conclusion

We have made a stylometric case that Harriet Taylor Mill's contribution to On Liberty is sufficiently substantial for her to count as co-author. We are not claiming that the evidence is conclusive, as further analyses starting from different assumptions might produce different results. Even though we are not able to say with a high degree of confidence which sections Harriet Taylor Mill wrote herself, we are confident that John Stuart Mill did not write On Liberty all by himself.

We also think there is evidence that John Stuart Mill might have thought his wife would not have approved of being listed as co-author, which would completely exonerate him from the charge of illegitimately downgrading her contribution even if it was as substantial as our evidence suggests. In the interest of historical accuracy and of giving credit where it is due, we suggest modern editions should list Harriet Taylor Mill as well as John Stuart Mill as authors of On Liberty.Footnote 67

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0953820821000339