When North Korean forces staged a massive surprise attack across the Korean 38th Parallel on June 25, 1950, overwhelming the defenses of the fledging Republic of Korea, President Harry Truman decided the US would act, quickly sending US forces and galvanizing the United Nations in support. Two and a half years later, as Truman departed the White House in January 1953, US and UN forces were still fighting Chinese as well as North Korean forces to a bloody stalemate along the 38th Parallel, armistice talks dragged on, and American public opinion on the Korean “police action” had soured. In this atmosphere Truman reflected on his eventful tenure that saw the end of World War II and the shaping of the post-War US-led order, and declared, “Most important of all, we acted in Korea…. The decision I believe was the most important in my time as President of the United States.”

The Armistice signed six months later, like the 1945 division of Korea itself, was meant to be temporary, pending a peace settlement. It was accompanied by a mutual security agreement between the Republic of Korea and the US, anxiously insisted upon by South Koreans who feared abandonment, and reached with acquiescence rather than enthusiasm by the US. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles said, “We had accepted (the Mutual Defense Treaty) as one of the prices we thought we were justified in paying to get the Armistice.”

It is safe to say that no one in 1953 would have predicted that seventy years later, the US–ROK relationship would be broader, deeper, stronger, and more important than ever, for both countries. This is rooted in a range of factors, some welcome, some concerning, including the extraordinary rise of South Korea to middle power status punching above its weight, the shift of economic and geopolitical weight to Asia and the rise of China, and North Korea’s continued pursuit of policies to maintain a totalitarian family dynasty by means, including nuclear weapons proliferation, that isolate it, oppress its people, and threaten the region.

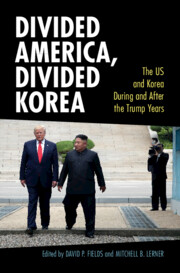

Over the last seventy years, South Koreans often fretted that the US was not paying enough attention to Korea. But every American president at some point in his tenure was confronted with the challenges of entanglement, commitment, and leverage in South Korea, and with the challenges of engaging or deterring North Korea. Donald Trump in this sense was no exception. Where Trump deviated from most of his predecessors (and most of his own national security staff) was in a deep-seated dislike of alliances in general and of South Korea in particular, and, with North Korea, in a readiness for saber-rattling and brinksmanship, for seat-of-the-pants, top-down bargaining, which ultimately was no more successful than earlier, more traditional diplomatic efforts.

The chapters in this volume are an essential antidote to focusing solely on the headline-grabbing Trump–Kim summits, and the “fire-and-fury” and “love letters” rhetoric that dominated American coverage of Korean issues during the Trump years. Indeed, America’s most important relationship on the Korean peninsula is with South Korea. And peaceful, lasting progress toward denuclearization and a permanent peace requires that Seoul and Washington work closely together.

The maturation and strengthening of the US–ROK alliance are directly related to South Korea’s own modern story. It is an extraordinary one: from poverty to prosperity, authoritarian rule to a thriving democracy, a “hermit kingdom” to an influential global player in technology, culture, and much more. None of this seemed likely at the end of the Korean War in 1953, which ensured the survival of the Republic of Korea but left it in ruins, still tragically divided, facing the rival Democratic People’s Republic of Korea to the north, and utterly reliant on the US. There is much inspiration – and some hard lessons – in South Korea’s blossoming, and in how the US–ROK relationship has broadened, deepened, and become more resilient – and more important to both countries – over the decades.

Diplomats are witnesses as well as sometimes participants in history, and I count myself fortunate to have lived in South Korea during three periods: first in the 1970s as a Peace Corps volunteer in authoritarian Korea as economic growth began to take off; next in the 1980s as an American diplomat covering South Korean domestic politics during decisive years in the struggle for democracy; and finally as the US Ambassador to South Korea from 2008 to 2011, the first Korean speaker and first woman to serve in that role.

I initially lived in rural South Korea as a Peace Corps volunteer from 1975 to 1977. Scarcity defined the country – scarcity of food and goods, scarcity of basic infrastructure, and, under its authoritarian government, inadequate civil and human rights. As volunteers we lived and worked in Korean homes and schools, where the unheated classrooms were so cold in the winter that I could see my breath and that of the seventy-plus middle school boys as they attempted to learn English – and I attempted to teach it. (Years later the same students told me that when teachers weren’t looking, they would splinter small wood pieces from their desks to light the dormant woodstove and warm their fingers.) Industrialization and urbanization were accelerating, though by gross domestic product (GDP) per capita measures South Korea was still near the bottom of the pile, along with North Korea. But change was happening, and was perceptible even in the countryside: More teachers (but few students) started commuting by bicycle rather than by foot; small refrigerators appeared at the village shop, stocking novelties like milk; Korea’s denuded hillsides were being reforested (I participated in numerous mass plantings myself) even as massive shipyards and auto plants were being constructed in former fishing villages. What was not in scarcity was human audacity and ambition, which I saw in Koreans’ fierce determination to put a terrible period behind them and focus on security, opportunity, and education for their children, and a discovery of pride and hope in a Korean state.

I went back to South Korea in the 1980s as a diplomat in the political section of the US embassy, serving there for six years. This time, the economy was booming more than ever, but political discontent was seething, along with demands for democratization. Once again Korean aspirations and determination took hold, and Korea turned decisively and irreversibly toward democracy. This political blossoming has not gotten the same attention as South Korea’s economic transformation, but it was just as unexpected and just as hard won. One of my jobs at the US embassy at the time was to write the Congressionally mandated human rights report on South Korea at a time when human rights was a major tension in the US–ROK alliance, and there was much to be concerned about. I spent a lot of time with opposition politicians and student, religious, and labor activists in the democratization movement, most of whom were highly critical of the perceived failure of the US to live up to its own ideals when it came to supporting democracy in Korea.

The US, which had come under increasing criticism for prioritizing security over political liberalization in earlier years, increasingly played a positive role. Secretary of State George Shultz and others in the Reagan administration surprised many Koreans with their insistence, both publicly and privately, on political progress. It was a good case study in quiet, and sometimes not so quiet, diplomacy.

But it was the South Korean people who demanded change – especially the university students who took to the streets and inspired many to join them with the demand for direct election of the next president. The 1988 Seoul Olympics were planned as South Korea’s great coming-out party; this too spurred the Chun government to agree to a new constitution, an election, and a host of other reforms. Since that decisive year of 1987, South Korea’s civil and democratic institutions have continued to take root, the military has stayed away from politics, and the country has never looked back.

I saw the many fruits of South Korea’s economic and democratic transformation when I returned as the US Ambassador in 2008. A sense of freedom, creativity, and innovation infused the life of the nation, from artists to inventors, to a vibrant press and public life. I often look back to my Peace Corps days and think with some wonder how far Korea has traveled. Today, from across the Pacific, as we routinely purchase South Korean products, drive Korean cars, and enjoy Korean cultural exports, it is easy to forget or take for granted the difficult journey Korea has traveled. But that story is central to the narrative of modern Korea, as is the fact of the continued division of the peninsula.

South Korea’s modern transformation has been accompanied by an evolving US–ROK relationship. It is a broader, deeper partnership rooted in shared values and strong people-to-people ties, and a deep, complex history. There have been major bumps and irritants along the way, including during the Trump administration. But relations between the US and the ROK remain strong, with broad public support in both countries. There has been, however, a growing need for a strategic review of their future alliance and relationship due to changes in the regional environment, especially as US–Chinese relations enter a troubled period, and as security and economic relationships evolve among the countries of the Indo-Pacific region.

The attention devoted to the US’s and South Korea’s relationships with North Korea has somewhat overshadowed South Korea’s identity as a powerful, technologically advanced country with strong democratic values and globally attractive soft power, gained through its well-known commercial brands and cultural exports. Shared values and common challenges – such as climate change and adaptation to advanced technologies – provide a foundation for productive future relations between the US and South Korea. Long-standing people-to-people relationships also serve as an enduring basis for friendly ties.

Nevertheless, the US and South Korea face coming policy choices that may bring them closer together or push them farther apart. One continuing challenge will be to ensure that policy coordination toward North Korea continues. Another challenge – or opportunity – comes from the Biden Administration’s return to multilateral diplomacy in the Asia-Pacific region and to an emphasis on human rights not only in North Korea but in China too.

It has been crudely put that South Korea will have to “choose” between the US and China, but this grossly oversimplifies a complex policy environment to the point of being misleading. All countries, including the US, will cooperate with China where possible, and resist China when it impinges on their interests. There is not one choice to be made, but hundreds of policy decisions, large and small. A still oversimplified but more accurate way to describe South Korea’s policy choices will be whether it will lean toward a “hedging strategy,” to be among countries that are more accommodating to China’s preferences, or whether it will be a fuller participant in a collective “shaping strategy” to nudge China toward rule- and norm-based behavior. In regard to multilateralism, the old distinction between security and economic frameworks is becoming irrelevant because the lines between defense and commercial technologies are blurring. The world is changing, not least because of the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath. The US and the ROK cannot avoid making fresh policy decisions and should not take their alliance and relationship for granted while doing so.

The eight essays collected here offer a first step toward moving the US–ROK relationship beyond the headline-grabbing behavior of the North’s nuclear program and Donald Trump’s salacious tweets. The authors scrutinize the economic connections and public diplomacy between the two allies, and consider the impact of soft power, internal politics, and human rights. They examine security issues on a broad level, and seek to fit China, Japan, and other nations into the complexity of current and future relations, in ways that transcend the simplistic friend/enemy dichotomy. Most of all, though, they take the relationship seriously by recognizing that the asymmetric power imbalance that marked my early years in Korea is no longer salient. Indeed, readers of this volume may well come away with the recognition that the two nations are now so deeply interconnected that no single issue or person – not even a president of the United States – can rip them asunder. It is imperative for the future of both nations and for the world that they remain that way.