Agomelatine is an antidepressant drug with a novel mechanism of action. It is the first antidepressant that targets the circadian system and mediates its therapeutic effect through the melatonergic system. It was approved for the treatment of unipolar major depression by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2009 and has been the focus of several narrative review articles Reference Arendt and Rajaratnam1–Reference Llorca6 describing its mechanism of action. Despite mainly focusing on the pharmacology of agomelatine, these narrative reviews extensively presented clinical trial data on efficacy and safety, making claims of efficacy in favour of agomelatine. One review Reference Hickie and Rogers4 was followed by a still ongoing debate regarding narrative v. systematic approaches to evidence synthesis, Reference Barbui and Cipriani7 and the true clinical efficacy of agomelatine. Reference Barbui and Cipriani8–Reference Hickie and Rogers14 A more critical narrative systematic review was published by Howland, Reference Howland15 who concluded that agomelatine has ‘a statistical significant, but clinically marginally relevant, antidepressant effect compared with placebo’. There is further evidence of agomelatine efficacy from a meta-analysis of published trials Reference Singh, Singh and Kar16 and from a pooled analysis of selected trials; Reference Montgomery and Kasper17 however, these reviews failed to evaluate agomelatine efficacy on the basis of a comprehensive systematic review of published and unpublished trials. This is a crucial issue in antidepressant trials, as several studies Reference Eyding, Lelgemann, Grouven, Harter, Kromp and Kaiser18–Reference Turner, Matthews, Linardatos, Tell and Rosenthal20 have illustrated the strong influence of publication bias on the overall estimates of treatment effect, and this may similarly apply to agomelatine trials. Reference Howland21 The present systematic review was therefore carried out to assess the evidence of efficacy and acceptability of agomelatine compared with placebo in the acute and long-term treatment of depression using all available evidence (either published or unpublished) and to evaluate the occurrence of publication bias.

Method

At the beginning of this project, a study protocol was drafted and made freely available to the public on our institutional website before carrying out the final analyses (online supplement DS1). Reference Koesters, Cipriani, Guaiana, Becker and Barbui22 Furthermore, with the publication of this paper the overall data-set will be in the public domain.

Types of studies and participants

This systematic review included published and unpublished double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, placebo-controlled trials. We included studies in adult patients (>18 years) with a primary diagnosis of unipolar major depression according to DSM-IV, 23 DSM-IV-TR 24 or ICD-10. 25 Studies including patients with a concurrent primary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder, and studies including participants with depression and with a concomitant medical illness, were excluded.

Types of intervention

Included trials compared agomelatine with placebo as monotherapy in the acute and relapse prevention treatment of depression. Only treatment arms within the therapeutic dose range of agomelatine (25–50 mg/d) were selected. No restrictions regarding pharmaceutical form or dose regimen (fixed or flexible) were applied.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure for acute-phase studies was the group mean score on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) at the end of the trial, or group mean change from baseline to end-point. Despite some criticism, Reference Bagby, Ryder, Schuller and Marshall26,Reference Isacsson and Adler27 the HRSD is recommended along with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) by the EMA 28 and used in most clinical trials assessing antidepressant efficacy. Reference Bagby, Ryder, Schuller and Marshall26,Reference Isacsson and Adler27 Clinical interpretation of results from meta-analyses are greatly simplified if effect sizes are calculated as (raw) mean differences. The primary outcome for long-term studies was the proportion of patients who relapsed during the follow-up treatment period. Any definition of depressive relapse according to the study authors was considered.

Secondary outcomes

For efficacy, we defined the following secondary outcomes.

-

(a) Group mean scores at the end of the trial, or group mean change from baseline to end-point, on any depression rating scale or Clinical Global Impression Rating scale (CGI). When trials reported results from more than one rating scale, we used the HRSD results or, if not available, the MADRS results. If none of the scales were available, we used the results at any other depression rating scale.

-

(b) Treatment responders, that is proportion of patients showing a reduction of at least 50% on the HRSD or MADRS or any other depression scale (for example the Beck Depression Inventory or the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)); or who were ‘much or very much improved’ (score 1 or 2) on the CGI – Improvement scale (CGI-I) or the proportion of patients who improved using any other pre-specified criterion.

-

(c) Treatment remitters, that is the proportion of patients with a score of seven or less on the 17-item HRSD, or eight or less on the longer versions of the HRSD; ten or less on the MADRS; ‘not ill or borderline mentally ill’ on the CGI – Severity scale (CGI-S); or any other equivalent value on a depression scale defined by the authors. Preference was given to remission rates defined by HRSD or MADRS scores.

For acceptability, we defined the following secondary outcomes.

-

(a) Total number of participants who dropped out during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants: total drop-out rate.

-

(b) Number of participants who dropped out as a result of inefficacy during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants.

-

(c) Number of participants who dropped out as a result of adverse events during the trial as a proportion of the total number of randomised participants.

-

(d) Total number of participants experiencing adverse events.

Search methods for identification of studies

Literature searches were performed using the following databases (last update: February 2012): MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycInfo, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Controlled vocabulary was utilised where appropriate terms were available, supplemented with keyword searches to ensure accurate and exhaustive results. Language or year limits were not applied to any search (online supplement DS2). In order to include unpublished studies, within the time frame of the electronic searches additional hand searches were performed on websites of pharmaceutical companies, clinical trials repositories and registers and regulatory agencies (online supplement DS2).

Data collection

Selection of studies

Included and excluded studies were collected following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman29 We examined all titles and abstracts, and obtained full texts of potentially relevant papers. Working independently and in duplicate, two reviewers read the papers and determined whether they met inclusion criteria. Considerable care was taken to exclude duplicate publications.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors, using an electronic data extraction form (EpiData EntryClient v1.1.1.1 for Windows), independently extracted the data on participant characteristics, intervention details and outcome measures. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consensus with a third member of the team. For continuous outcomes, the mean scores at end-point or the mean change from baseline to end-point, the standard deviation or standard error of these values, and the number of patients included in these analyses, were extracted. Reference Norman30 For dichotomous outcomes, the number of patients undergoing the randomisation procedure, the number of patients rated as having responded, remitted or relapsed and the number of patients leaving the study early were recorded.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green31 was used. This instrument consists of six items. Two of the items assess the strength of the randomisation process in preventing selection bias in the assignment of participants to interventions, adequacy of sequence generation and allocation concealment. The third item assesses the influence of performance bias on the study results. The fourth item assesses the likelihood of incomplete outcome data, which raise the possibility of bias in effect estimates. The fifth item assesses selective reporting, the tendency to preferentially report statistically significant outcomes. This item requires a comparison of published data with trial protocols, when these are available. The final item refers to other sources of bias (for example sponsorship bias).

Summary statistics

A double-entry procedure was employed. Data were initially entered and analysed using the Cochrane Collaboration's Review Manager software version 5.1 for Windows, 32 and subsequently entered into a spreadsheet and re-analysed using the ‘metafor’ package. Reference Viechtbauer33 Outputs were cross-checked for internal consistency. When outcome data were not reported, trial authors were asked to supply the data.

Continuous data

The primary outcome data (acute treatment studies) were analysed by calculating the overall mean differences of studies that used the HRSD. As a secondary outcome, data were analysed using standardised mean differences (SMD), as this measure of treatment effect allows the combining of scores from different depression scales. If end-point data were unavailable, change score data were analysed. Where intention-to-treat (ITT) data were available, these were preferred over ‘per-protocol analysis’. When only P or standard error values were reported, standard deviations were calculated.

Dichotomous outcomes

For dichotomous outcomes a Mantel-Haenszel risk ratio was calculated. Response, remission and relapse rates were calculated using an ITT analysis: if participants left the study before the intended end-point, it was assumed that they had experienced the negative outcome. In case of missing information, we estimated the number of patients responding to treatment using a validated imputation method. Reference Furukawa, Cipriani, Barbui, Brambilla and Watanabe34,Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Geddes, Higgins and Churchill35 The robustness of this approach was checked in a sensitivity analysis.

Confidence intervals

A 99% confidence interval was calculated for all efficacy estimates according to Barbui and colleagues. Reference Barbui, Furukawa and Cipriani36 This approach, instead of a 95% confidence interval approach, was adopted to have the widest estimate of likely true effect. We set the level of significance at 0.01 as we made multiple comparisons and reasoned that only robust differences between treatments should inform clinical practice. In fact, it is more important to avoid the possibility of showing a difference in the absence of a true difference, than to avoid the possibility of not showing a difference in the presence of a true difference. In other words, we gave priority to avoiding a type I rather than a type II error. Reference Cipriani, Brambilla, Furukawa, Geddes, Gregis and Hotopf37 Conversely, a 95% confidence interval was calculated for all tolerability estimates. In terms of tolerability it is more important to avoid the possibility of not showing a difference in the presence of a true difference than to avoid the possibility of showing a difference in the absence of a true difference. In other words, we gave priority to avoiding a type II rather than a type I error.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

For dichotomous outcomes, trials comparing different doses of agomelatine with placebo were converted into two-arm trials by summing samples and averaging doses. For continuous outcomes, means and standard deviations of different dosage arms were combined into a single arm according to the Cochrane Handbook. Reference Higgins, Deeks, Higgins and Green38

Assessment of heterogeneity

Visual inspection of graphs was used to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented using the I 2 statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of variability due to heterogeneity rather than chance alone. Where the I 2 estimate was greater than or equal to 50% we interpreted this as indicating the presence of high levels of heterogeneity. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman39 Statistical significance of heterogeneity was additionally tested with χ2-tests, using a threshold of P<0.20 as the threshold of statistical significance, because the power of this test is known to be low if the number of studies included is small. Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman39

Assessment of publication bias

For the primary outcome, the funnel plot approach was used to investigate publication bias.

Data synthesis and presentation

Continuous and dichotomous outcomes were analysed using a random-effects model, as this takes into account any differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green31 A summary of findings table was produced according to the methodology described by the GRADE working group. Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, Vist, Falck-Ytter and Schunemann40,Reference Guyatt, Oxman, Vist, Kunz, Falck-Ytter and Alonso-Coello41

Subgroup analyses

The following pre-planned subgroup analyses were carried out: (a) agomelatine dose (low dosage: 25 mg/d v. flexible doses and 50 mg/d); (b) publication status (published v. unpublished studies); (c) data imputation (file v. imputed).

Results

Characteristics of included studies

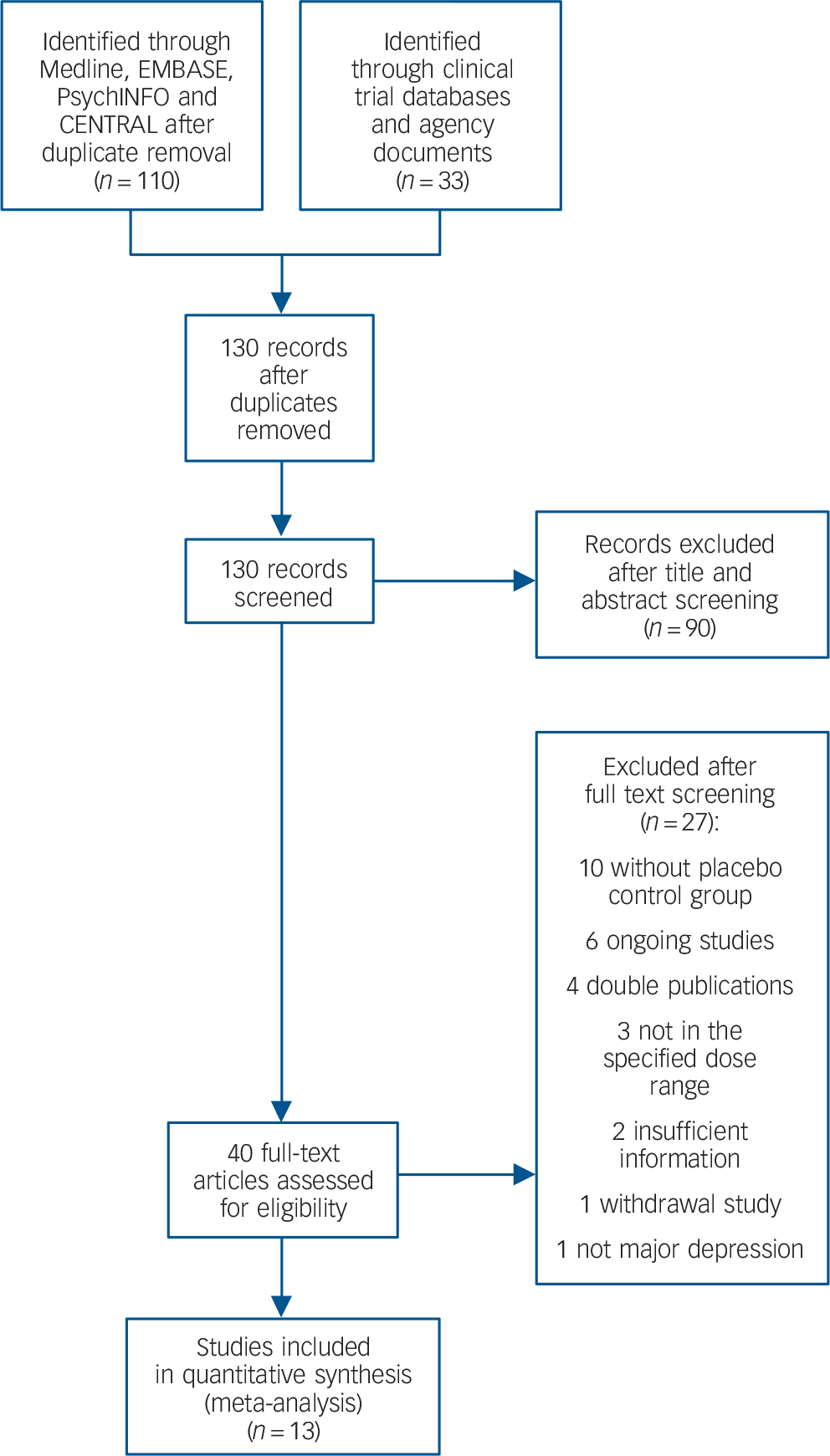

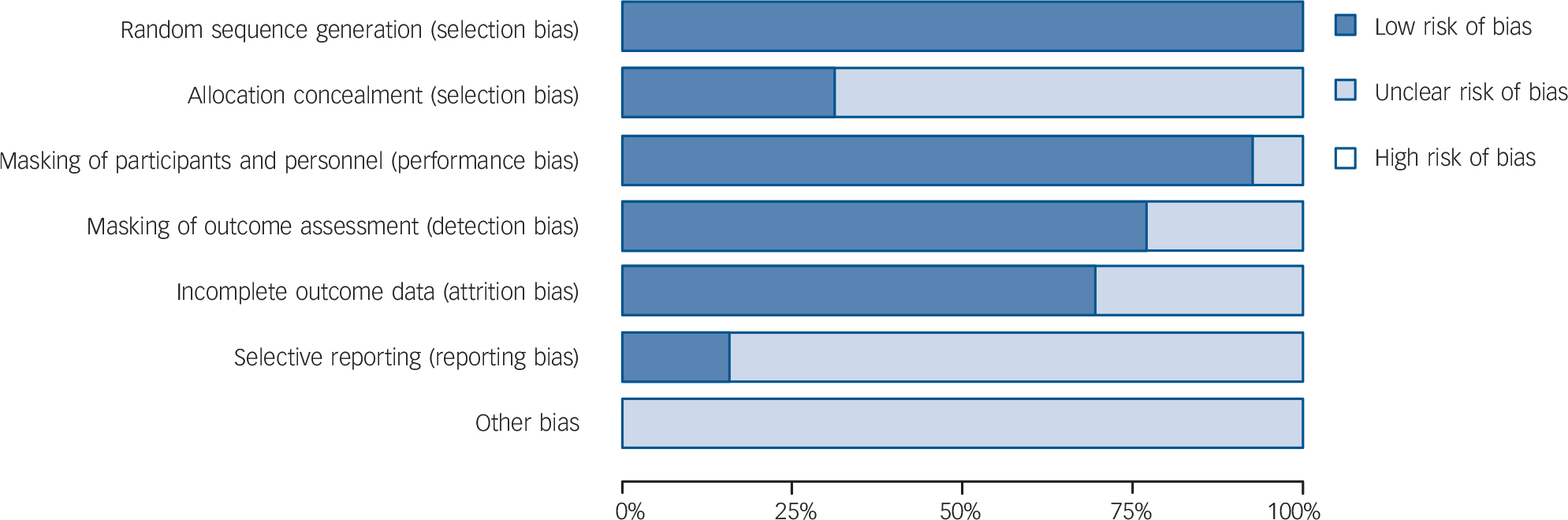

From 130 potentially relevant records from the search of databases and additional sources, 90 were excluded on the basis of title or abstract. The remaining 40 studies were retrieved for more detailed evaluation (Fig. 1). Overall, 13 studies, 42–Reference Zajecka, Schatzberg, Stahl, Shah, Caputo and Post54 including 7 unpublished studies, 42–46,50,51 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 10 43–46,Reference Kennedy and Emsley48–50,Reference Olie and Kasper52–Reference Zajecka, Schatzberg, Stahl, Shah, Caputo and Post54 were short-term studies and 3 42,Reference Goodwin, Emsley, Rembry and Rouillon47,51 were long-term relapse prevention studies (see online supplement DS3 for references of the 27 excluded studies). The main characteristics of the 13 studies are reported in Table 1. All comparisons included more than 100 patients per treatment arm, the length of follow-up ranged between 6 and 52 weeks. One study 45 was carried out in individuals aged 60 or above. None of the studies recruited patients in primary healthcare settings. All studies were financially supported by agomelatine manufacturing companies. The overall quality of reporting was graded as moderate to good (Fig. 2, online supplement DS4, online Fig. DS1 and online Table DS1).

Efficacy of agomelatine

Primary outcomes

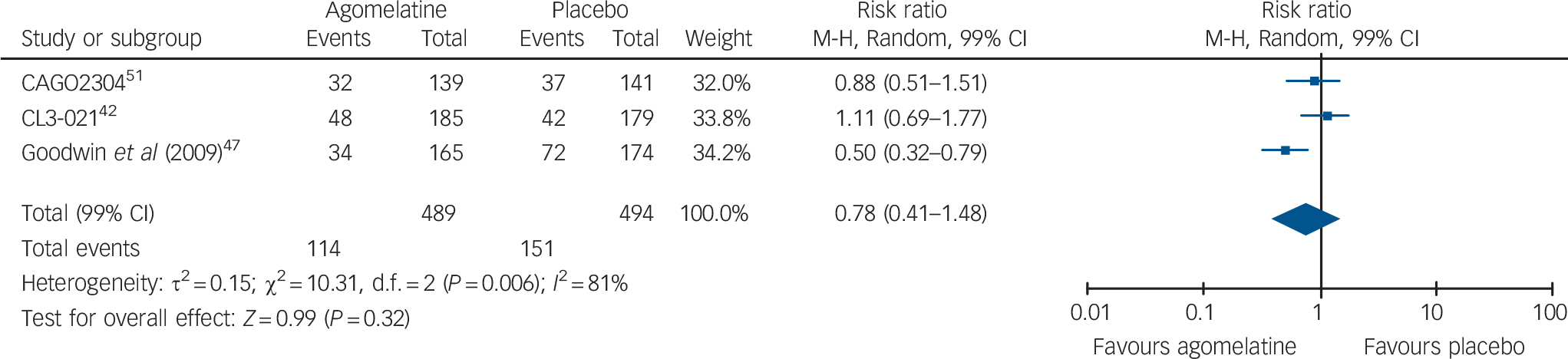

With the exception of one study, 45 all studies reported HRSD scores. Acute-phase studies (9 studies, overall 2947 patients) indicated that acute treatment with agomelatine is associated with a statistically significant difference over placebo of −1.51 points on the HRSD (99% CI −2.29 to −0.73) (Fig. 3). The subgroup analysis comparing published v. unpublished trials revealed a difference of −1.39 HRSD points (P = 0.02) between unpublished (mean difference: −0.73, 99% CI −1.90 to 0.45) and published trials (mean difference: −2.12, 99% CI −3.16 to −1.08, Fig. 3). In terms of risk of relapse, data extracted from three long-term studies (overall 983 patients) failed to show any significant effect of agomelatine over placebo (relative risk = 0.78, 99% CI 0.41–1.48, Fig. 4).

Secondary outcomes

The analysis of secondary outcomes is summarised in Table 2 and fully reported in online Figs DS2–7. In terms of response the data extracted from the 10 acute-phase studies (overall 3295 patients) showed a significant advantage of agomelatine over placebo (online Fig. DS2), whereas in terms of remission (7 studies, overall 2346 patients) no difference was found between agomelatine and placebo (online Fig. DS3). Both analyses showed a statistically significant effect of agomelatine in the subgroup of published trials only.

In the analysis of depressive symptoms where scores from different rating scales were pooled, data extracted from the 10 acute-phase studies (2896 patients) indicated that acute treatment

Fig. 1 Included and excluded studies with reasons: flow of information through the different phases according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). CENTRAL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials.

with agomelatine is associated with an SMD over placebo of −0.18 (99% CI −0.27 to −0.08) (Table 2, online Fig. DS4). When studies were grouped into published v. unpublished, a significant antidepressant effect of agomelatine was shown in the subgroup of published trials only.

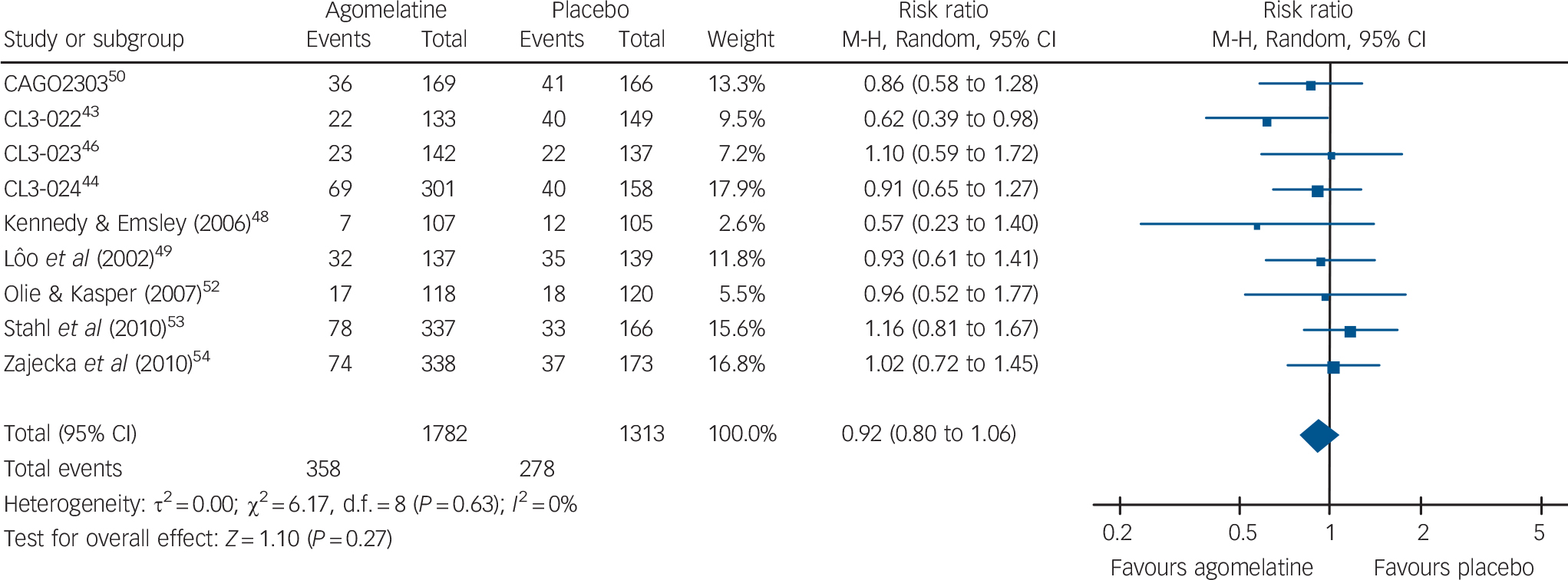

Acceptability and tolerability of agomelatine

In terms of overall acceptability, data extracted from 9 acute-phase studies (1782 patients treated with agomelatine and 1313 with placebo) failed to show a significant difference between agomelatine and placebo (Fig. 5). Whereas discontinuation because of inefficacy significantly favoured agomelatine (online Fig. DS5), discontinuation because of adverse events did not differ between agomelatine and placebo (Table 2 and online Fig. DS6). Similarly, no difference emerged from the analysis of the proportion of patients reporting adverse events (Table 2 and online Fig. DS7).

Table 1 Overview of the characteristics of the included studies

| Study identifier/ trial registration number |

Years of patient recruitment |

Weeks of follow-up |

Agomelatine dose mg/day |

Setting | Allocated to agomelatine n |

Allocated to placebo n |

Diagnostic criteria |

Severity of depression |

Age | Medical comorbidities |

Publication status/ reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAGO2303/NCT00463242 | 2007–2008 | 8 | 25–50 | nr | 169 | 166 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–70 | No | Unpublished 50 |

| CAGO2304/NCT00467402 | 2007–2009 | 52 | 25–50 | nr | 140 | 141 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–70 | No | Unpublished 51 |

| CL3-021/– | 1999–2002 | 34 | 25 | nr | 187 | 180 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 19–67 | nr | Unpublished 42 |

| CL3-022/– | 1999–2001 | 6 | 25 | In- and out-patients | 133 | 149 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–59 | nr | Unpublished 43 |

| CL3-023/– | 1999–2001 | 6 | 25 | In- and out-patients | 142 | 137 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–59 | nr | Unpublished 46 |

| CL3-024/– | 2000–2002 | 6 | 25 or 50 | In- and out-patients | 301Footnote a | 158 | DSM–IV | Moderate to severe | 18–59 | nr | Unpublished 44 |

| CL3-026/– | nr | 6 | 25 | In- and out-patients | 109 | 109 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | ≥60 | nr | Unpublished 45 |

| Goodwin et al (2009)/ISRCTN53193024 | 2005–2007 | 24 | 25–50 | Out-patients | 165 | 174 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–65 | No | Published Reference Goodwin, Emsley, Rembry and Rouillon47 |

| Kennedy & Emsley (2006)/– | 2002–2004 | 6 | 25–50 | In- and out-patients | 107 | 105 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–65 | No | Published Reference Kennedy and Emsley48 |

| Lôo et al (2002)/– | nr | 8 | 25 | nr | 137Footnote b | 139 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 19–65 | nr | Published Reference Lôo, Hale and D'haenen49 |

| Olie & Kasper (2007)/– | nr | 6 | 25–50 | In- and out-patients | 118 | 120 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–65 | No | Published Reference Olie and Kasper52 |

| Stahl et al (2010)/NCT00411242 | 2006–2008 | 8 | 25 or 50 | nr | 337Footnote c | 166 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–70 | No | Published Reference Stahl, Fava, Trivedi, Caputo, Shah and Post53 |

| Zajecka et al (2010)/NCT00411099 | 2006–2008 | 8 | 25 or 50 | nr | 338Footnote d | 173 | DSM-IV | Moderate to severe | 18–70 | No | Published Reference Zajecka, Schatzberg, Stahl, Shah, Caputo and Post54 |

nr, not reported.

a. 25 mg group n = 150, 50 mg group n = 151.

b. 25 mg group.

c. 25 mg group n = 168, 50 mg group n = 169.

d. 25 mg group n = 170, 50 mg group n = 168.

Fig. 2 Methodological quality graph: risk of bias item presented as percentage of studies with low, unclear or high risk of bias.

Fig. 3 Random-effects meta-analysis of the effect of agomelatine v. placebo on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scores.

Agomelatine dose

Data extracted from studies that employed a fixed dose of 25 mg/d of agomelatine (mean difference: −1.47, 99% CI −2.50 to −0.44, 6 studies, 1696 participants) provided a similar overall estimate compared with studies that employed a flexible dose scheme of 25–50 mg/d or a fixed dose of 50 mg/d (mean difference: −1.57, 99% CI −2.90 to −0.24, 6 studies, 1644 participants) (online Fig. DS8).

Data imputation and publication bias

The exclusion of studies with imputed data did not change the overall findings (online Fig. DS9). The funnel plot did not suggest the occurrence of publication bias, although it clearly showed that the omission of the unpublished trials that we were able to include would have led to a biased overall estimate (online Fig. DS10).

Discussion

Main findings

The present systematic review found that acute treatment with agomelatine is associated with a difference of 1.5 points on the HRSD. This difference was statistically significant, although the clinical relevance of this small effect is questionable. No research evidence or consensus is available about what constitutes a clinically meaningful difference in HRSD scores. Antidepressant research has recently faced the issues of (a) a large number of studies reporting negative findings and (b) a possible increase in placebo response rates, which may be caused by changes in selection of study participants and how studies are conducted. Reference Undurraga and Baldessarini55 Such changes might contribute to a reduction in the likelihood of identifying drug effectiveness in antidepressant drug trials.

Fig. 4 Random-effects meta-analysis of the effect of agomelatine v. placebo on the risk of relapse in long-term studies.

Table 2 Analysis of secondary outcomes in randomised trials comparing agomelatine with placeboFootnote a

| Studies | Agomelatine n/N |

Placebo n/N |

Effect size (CI) | Measure | I 2, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Failure to respond | 10 | 971/1878 | 830/1417 | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.94) | RR (99% CI) | 0 |

| Failure to show remission | 7 | 1098/1333 | 867/1013 | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.05) | RR (99% CI) | 70 |

| Depressive symptoms | 10 | 1763 | 1133 | –0.18 (–0.27 to −0.08) | SMD (99% CI) | 2 |

| Discontinuation due to inefficacy | 8 | 58/1481 | 88/1155 | 0.60 (0.43 to 0.83) | RR (95% CI) | 0 |

| Discontinuation due to adverse events | 8 | 65/1481 | 54/1155 | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.30) | RR (95% CI) | 0 |

| Any adverse event | 6 | 777/1188 | 557/861 | 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | RR (95% CI) | 0 |

RR, risk ratio; SMD, standardised mean difference.

a. See online Figs DS2-7.

Fig. 5 Random-effects meta-analysis of the effect of agomelatine v. placebo on treatment discontinuation by any cause.

However, even with this consideration in mind, it is plausible to agree with one of the agomelatine clinical trials Reference Stahl, Fava, Trivedi, Caputo, Shah and Post53 that a difference of less than three HRSD points is unlikely to be clinically meaningful. Other publications have discussed a difference of two points as being clinically important, Reference Montgomery and Moller2,Reference Melander, Salmonson, Abadie and van Zwieten-Boot56 but the effect of agomelatine in our review was also below this threshold. Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that a 1.5-point difference may reflect a weak effect on sleep-regulating mechanisms rather than a genuine antidepressant effect.

In a recent statement, the EMA Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) pointed out that, in addition to a statistically significant effect in symptom scale scores, the clinical relevance has to be confirmed by responder and remitter analyses and that ‘… results in the short-term trials need to be confirmed in clinical trials, to demonstrate the maintenance of effects’. Reference Broich57 For dichotomous outcomes, agomelatine was not superior to placebo in terms of relapse and remission rates, but was statistically superior to placebo in terms of response rates. The difference in response rates corresponds to an absolute risk difference of 6% and to a number needed to treat (NNT) of 15. Based on an analysis of regulatory submissions, Reference Melander, Salmonson, Abadie and van Zwieten-Boot56 which found an average difference of 16% in the response rates between common antidepressants and placebo, EMA CHMP states that this difference ‘… is considered to be the lower limit of the pharmacological effect that would be expected in clinical practice.’ Reference Broich57 Other authors Reference Montgomery and Moller2 considered an NNT of ten or below as clinically relevant. Clearly, the effect size in the present analysis is of doubtful clinical significance. This point is strengthened by the fact that depression is a clinical condition for which many active antidepressants are already available. 58

Doubt emerged regarding the value of agomelatine as a first-line agent when Novartis dropped the agomelatine development programme, 59 and the current manufacturer has informed the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) that it would not be making an evidence submission for the appraisal of agomelatine for the treatment of major depressive episodes. 58 Based on the results presented in this review, we suggest that agomelatine should not be used as a first-line treatment in patients with major depression.

Problems with current methods for approving new drugs

In Europe new drugs are approved or rejected on the basis of the results of studies carried out by the manufacturer and submitted to the EMA. We note that decisions are taken on the basis of the results of individual studies with no role for aggregating efficacy data using meta-analytic techniques. We argue, however, that pooling studies would have some beneficial consequences for the review process by increasing statistical power and by contributing to the detection of between-study heterogeneity.

Additionally, the EMA should require submission of all available studies, without allowing manufacturers to submit only a selection of clinical trials. For example, in the agomelatine European Assessment Report (EPAR) two of the three long-term studies are included, and these two studies were assessed using a questionable narrative approach. The EMA reports: ‘in the first of the long-term studies, there was no difference between Valdoxan and placebo in preventing symptoms returning during 26 weeks of treatment. However, the second study showed that symptoms returned in 21% of the patients taking Valdoxan over 24 weeks (34 out of 165), compared with 41% of the patients taking placebo (72 out of 174)’. 60

The present systematic review showed that pooling the three long-term studies failed to show a difference between agomelatine and placebo in terms of relapse rate, but even if the two studies included in the EMA assessment had been pooled, lack of agomelatine efficacy would have been found. According to the earlier-mentioned CHMP statement, Reference Broich57 the lack of long-term effects further limits the clinical relevance of the effect of agomelatine. We argue that the EMA qualitative approach should be assisted by a quantitative approach to data synthesis.

Limitations

This systematic review has some limitations. Although we were able to include several unpublished studies, uncertainty remains as to whether other randomised studies have been carried out and never published or disseminated on the World Wide Web. This is a major issue as we have demonstrated that the results of unpublished agomelatine studies were systematically less favourable in comparison with published ones. It is therefore possible that the true effect of agomelatine might be smaller than the effect we calculated in the present systematic review. Also, comparative head-to-head studies were not included. According to the study protocol, the aim of the present study was to assess efficacy and acceptability of agomelatine combining both published and unpublished placebo-controlled trials. We acknowledge that comparative effectiveness is of paramount relevance in a field characterised by many active treatments, but we reasoned that a standard direct meta-analysis was not the most suitable methodological approach. When a new drug is compared with several other treatments, more sophisticated approaches integrating direct and indirect evidence have been developed and already applied to antidepressants. Reference Cipriani, Furukawa, Salanti, Geddes, Higgins and Churchill35 It is likely that the introduction of agomelatine in these network analyses with other antidepressants and placebos will shed light on the relative value of this new drug.

To analyse efficacy we employed a 99% confidence interval. This is not the standard way to assess efficacy, as usually a 95% confidence interval is preferred in all outcomes. However, we decided a priori to apply this method because it has been used previously in the field of placebo-controlled antidepressant trials and shown to be the most clinically informative. Reference Barbui, Furukawa and Cipriani36,Reference Cipriani, Brambilla, Furukawa, Geddes, Gregis and Hotopf37

The extent of publication bias found in the present review was surprising. None of the negative trials were published, and the standardised effect size was more than three times higher in published than in unpublished trials. However, Singh and colleagues Reference Singh, Singh and Kar16 also questioned the clinical relevance of the antidepressant effect of agomelatine, although their meta-analysis included published trials only. Publication bias was even more obvious in relapse prevention trials. There is only one positive trial published suggesting that agomelatine is effective in relapse prevention. The present review included unpublished data from 1908 patients and published data on 2022 patients randomised to short- or long-term trials of agomelatine. Thus, only about 50% of the data available was published. Furthermore, only the minority of studies included were registered in public trial databases. This indicates that clinical trial registration in its current form has not yet solved the issue of publication and outcome reporting bias. As has already been suggested, Reference G⊘tzsche61 better access to clinical trial data would make them more useful for doctors, researchers and consumers.

Acknowledgements

We thank Katja Häderle and Lena Staudigl for their help with the literature and data management.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.