Introduction

Marital satisfaction is one of the most important variables related not only to marital stability (Karney and Bradbury, Reference Karney and Bradbury1995) but also to individuals’ wellbeing (Proulx et al., Reference Proulx, Helms and Buehler2007; Kamp Dush et al., Reference Kamp Dush, Taylor and Kroeger2008; Margelisch et al., Reference Margelisch, Schneewind, Violette and Perrig-Chiello2017). In the age of marriage deterioration (Amato, Reference Amato2010), it is especially important to investigate the mechanisms underlying marital satisfaction. Although it seems to be a very exploited concept (Shafer et al., Reference Shafer, Jensen and Larson2014), previous studies have led to different ways of predicting marital satisfaction due to their designs, diverse samples, research durations, data collection and marital satisfaction operationalisations, as well as focus on younger couples and negative interactions between partners (Bradbury et al., Reference Bradbury, Fincham and Beach2000; Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Miller, Oka and Henry2014; Proulx et al., Reference Proulx, Ermer and Kanter2017). Thus, understanding and promoting marital satisfaction is still incomplete (Karney and Bradbury, Reference Karney and Bradbury2020) and need to be addressed (Tavakol et al., Reference Tavakol, Nikbakht Nasrabadi, Behboodi Moghadam, Salehiniya and Rezaei2017). As marital satisfaction is usually defined as spouses’ global subjective evaluation about the quality of their marriage (Li and Fung, Reference Li and Fung2011), it might be dependent on many factors, emanating from individuals and interactions between them (Luo et al., Reference Luo, Chen, Yue, Zhang, Zhaoyang and Xu2008), as well as from external circumstances (Henry and Miller, Reference Henry and Miller2004). In searching for the most prominent predictors, the associations between personal characteristics (e.g. personality traits, attitudes and values) and marital satisfaction have received much attention and brought interesting findings. However, examining such simple links in isolation from other variables may provide incomplete or even misleading results because spouses’ characteristics are inherently related to interactional processes in marriage (Bradbury and Karney, Reference Bradbury and Karney2004) and have a dynamic nature (Shiota and Levenson, Reference Shiota and Levenson2007), as individuals and couples change over their lifetime (Roberts and Mroczek, Reference Roberts and Mroczek2008; Li and Fung, Reference Li and Fung2011).

This study proposes a comprehensive model, testing both individual characteristics and spouses’ responses to particular events in the marital context, from a lifespan development perspective. It explores the relationships between personality traits, forgiveness in marriage and marital satisfaction in long-term continuously married older individuals.

The theoretical basis underpinning this research is the theory of gerotranscendence by the Swedish researcher Lars Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2005, Reference Tornstam2011). This concept presents a new way of understanding and interpreting ageing, making it a valuable research perspective that captures the dynamics of development in its declining phase (Wadensten, Reference Wadensten2005, Reference Wadensten2010). According to Tornstam (Reference Tornstam1989), gerotranscendence can be understood as a natural, cultural-free developmental process that is clearly activated in mid-adulthood and leads to increased life satisfaction and wisdom. As part of this process, an older person experiences a number of changes in the area of psycho-social functioning. Tornstam (Reference Tornstam1989) claims these changes can be ordered on three basic levels: cosmic, self and social. At the cosmic level, there are transformations in the perception of time and space. The person more and more clearly feels the need to be open to the spiritual aspect of existence. In the dimension related to the self, among the most important transformations there is a change in the concept of self, expressed in the acceptance of both positive and negative aspects of one's personality, a decrease in egocentrism and an increase in altruistic attitudes. Finally, in the social and personal relationships dimension, the relationships are re-evaluated. Quality is becoming more important than before, not the number of relationships with others (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005; Brudek, Reference Brudek2016, Reference Brudek2017).

Personality traits and marital satisfaction

The research on personality and marital outcomes has a long history. Numerous studies have used the Big Five and Five Factor models to explore the link between spouses’ personality traits and quality of their marriage (e.g. Karney and Bradbury, Reference Karney and Bradbury1995; Claxton et al., Reference Claxton, O'Rourke, Smith and DeLongis2012; Lavner et al., Reference Lavner, Weiss, Miller and Karney2017). The most consistent and strongest personality predictor of marital dissatisfaction has been neuroticism (Heller et al., Reference Heller, Watson and Ilies2004; Cao et al., Reference Cao, Yuan, Fine, Zhou and Fang2019), whereas extraversion has been found to associate with positive interactions and global evaluations of the marriage (e.g. O'Rourke et al., Reference O'Rourke, Claxton, Chou, Smith and Hadjistavropoulos2011; Kumari, Reference Kumari2017). Openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness have been generally, but less reliably and less strongly, positively correlated with marital satisfaction (Donnellan et al., Reference Donnellan, Conger and Bryant2004; Claxton et al., Reference Claxton, O'Rourke, Smith and DeLongis2012).

On the other hand, some studies have failed to reveal direct relationships between personality domains and marital satisfaction, but their findings suggest indirect effects via other factors correlated with both (Heller et al., Reference Heller, Watson and Ilies2004). As personality does not work by itself but is expressed in everyday behaviour, identifying the actions through which personality operates in favour of quality of marriage might be more important than testing simple relationships between personality trait and marital satisfaction. Moreover, since most research has been conducted among younger couples, their results may not be applicable to older people. Both the personality changes over the lifetime (e.g. Roberts and DelVecchio, Reference Roberts and DelVecchio2000; Allemand et al., Reference Allemand, Zimprich and Hendriks2008) and the developmental and role changes in later life may modify understanding of the association between personality and marital quality.

Personality, expressed in terms of features, is generally treated as a relatively stable (permanent) structure (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa1989, Reference McCrae and Costa2003). However, some reports claim that the intensity of personality traits changes throughout life, including late adulthood (cf. Ardelt, Reference Ardelt1997; Lazarus and Lazarus, Reference Lazarus and Lazarus2006). These accord with Pervin and John (Reference Pervin and John2002), who claim that the ageing process reveals small, clear changes in the individual dimensions of the personality structure. They become much more pronounced when comparing older adults with people representing other age groups (see Ardelt, Reference Ardelt2003; Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005). With this in mind, it can be assumed that the change in the area of relationships with other people, expressed in undertaking altruistic actions and reduction of self-focus, reported by Tornstam (Reference Tornstam2005, Reference Tornstam2011), is connected with the intensification of the trait of agreeableness. In turn, the characteristic for gerotranscendence, a decrease in interest in superficial relations with other people, or the desire to establish new bonds, with the intention of strengthening and deepening old friendships and relationships with close family members (spouse, children, grandchildren), may signal a decrease in the extraversion component – the dimension determining the quality and the amount of social interaction as well as the level of activity, energy and the ability to feel positive emotions. Pursuing this way of thinking, it can be expected that the signs of the gerotranscendence process – the recognition and acceptance by the individual of positive and negative sides – is the effect of a decrease in neuroticism, and especially one of its components, excessive self-criticism, the main manifestations of which are the emotions of shame and embarrassment (McCrae and Costa, Reference McCrae and Costa1989, Reference McCrae and Costa2003).

As a result of gerotranscendent transformations revealed at the level of social references, seniors have an increased need for positive loneliness, which is accompanied by increased reflectiveness. It allows the conscious acceptance of ambiguity, giving up the superficial separation of good from evil and refraining from issuing fast judgements (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005). These new properties, which are a consequence of the gerotranscendence process, become an important context in the overall balance of life, including the area of marital relations (Lazarus and Lazarus, Reference Lazarus and Lazarus2006). As a consequence, what was once the subject of harm and suffering, today, in retrospect, subjected to redefinition, may become the subject of forgiveness that will strengthen the bond between spouses (Brudek, Reference Brudek2015; Brudek and Steuden, Reference Brudek and Steuden2017). Thus, more complex models, as well as focusing on particular age groups, are required.

Forgiveness and marital satisfaction

In a long-term marriage, multiple transgressions are likely to occur in the course of life and have the potential to disrupt the relationship (Fincham, Reference Fincham2000). Forgiveness is one of the most important positive ways of dealing with marital injuries and their consequences, and has been found to be an important component of marital satisfaction (Fincham, Reference Fincham2000; Fincham and Beach, Reference Fincham and Beach2002; Fincham et al., Reference Fincham, Beach and Davila2004; Paleari et al., Reference Paleari, Regalia and Fincham2005; Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen, Reference Orathinkal and Vansteenwegen2006; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Hughes, Tomcik, Dixon and Litzinger2009; Bugay, Reference Bugay2014).

In the context of marriage, forgiveness refers to a single act (episodic forgiveness) or general tendency (dispositional forgiveness) to forgive a spouse for a particular offence or multiple transgressions (Paleari et al., Reference Paleari, Regalia and Fincham2009). Offence-specific forgiveness is usually understood as a process of abandoning negative thoughts, emotions, motivation and behaviour towards the offender (McCullough et al., Reference McCullough, Worthington and Rachal1997; Rye and Pargament, Reference Rye and Pargament2002). However, some scholars suggest that forgiveness in close relationships needs two dimensions (Fincham and Beach, Reference Fincham and Beach2002; Wade and Worthington, Reference Wade and Worthington2003; Fincham et al., Reference Fincham, Hall and Beach2006; Gordon et al., Reference Gordon, Hughes, Tomcik, Dixon and Litzinger2009): a negative one, that entails the degree to which an individual overcomes nurturing grudges, withdrawing from the relationship, and desire for revenge or punishment against the partner, and a positive one, involving the degree to which an individual experiences a readiness to get closer to the partner and an increase in empathy and benevolence. In a long-lasting relationship, like marriage, both components are important to resume closeness (Fincham et al., Reference Fincham, Hall and Beach2006). Moreover, it turns out that older people are more willing to forgive their resentments than those in early adulthood (see McCullough and Witvliet, Reference McCullough, Witvliet, Snyder and Lopez2002; Allemand et al., Reference Allemand, Zimprich and Hendriks2008; Cheng and Yim, Reference Cheng and Yim2008; Hill and Allemand, Reference Hill and Allemand2010; Ghaemmaghami et al., Reference Ghaemmaghami, Allemand and Martin2011). It has also been shown that forgiveness of a partner positively correlates with satisfaction from marriage – it increases intimacy and commitment to the relationship, promotes effective resolution of conflicts and, over time, has a positive impact on the quality of marriage (see Paleari et al., Reference Paleari, Regalia and Fincham2005, Reference Paleari, Regalia and Fincham2009; Tsang et al., Reference Tsang, McCullough and Fincham2006; Fincham et al., Reference Fincham, Beach and Davila2007).

Personality and forgiveness

Forgiveness itself depends on various factors and some people are more prone than others to forgive because of their personality characteristics, like empathy, narcissism or general personality traits (Walker and Gorsuch, Reference Walker and Gorsuch2002; Brown, Reference Brown2003, Reference Brown2004). Personality constitutes whether a person is positive or hostile towards a spouse after having been hurt, mitigates a partner's faults or exaggerates them, nurtures anger or easily calms down, co-operates or fights. These characteristics affect a person's willingness to forgive, which in turn makes one's marriage more satisfying. Among different traits, five personality domains have been the most frequently explored in the context of forgiveness (McCullough and Witvliet, Reference McCullough, Witvliet, Snyder and Lopez2002; Mullet et al., Reference Mullet, Neto, Riviere and Worthington2005).

All five personality traits are known to influence forgiveness, both as a state and as a disposition (e.g. Berry et al., Reference Berry, Worthington, Parrott, O'Connor and Wade2001; McCullough and Hoyt, Reference McCullough and Hoyt2002; Walker and Gorsuch, Reference Walker and Gorsuch2002). Neuroticism, which entails anxious rumination and an impaired emotion regulation capacity, is a well-documented domain inversely correlated with forgiveness (Brose et al., Reference Brose, Rye, Lutz-Zois and Ross2005; Maltby et al., Reference Maltby, Wood, Day, Kon, Colley and Linley2008; Hill et al., Reference Hill, Allemand and Burrow2010; Rey and Extremera, Reference Rey and Extremera2014). Agreeableness, predisposing individuals to maintain more friendly interpersonal relations, has shown a positive association with forgiveness (Brown, Reference Brown2003; Koutsos et al., Reference Koutsos, Wertheim and Kornblum2008; Rey and Extremera, Reference Rey and Extremera2016). Taking other personality traits into account, only a few studies have confirmed positive relationships between conscientiousness and forgiveness (Kamat et al., Reference Kamat, Jones and Row2006; Rey and Extremera, Reference Rey and Extremera2014, Reference Rey and Extremera2016), extraversion and forgiveness (Maltby et al., Reference Maltby, Day and Barber2004; Ross et al., Reference Ross, Kendall, Matters, Rye and Wrobel2004) and between openness to experience and forgiveness (Hafnidar, Reference Hafnidar2013; Abid et al., Reference Abid, Shafiq, Naz and Riaz2015).

However, limited studies have examined the relationship between personality traits and forgiveness in the context of marriage. Scholars have usually relied on studies that tested personality and forgiveness of a romantic partner (e.g. McCullough and Hoyt, Reference McCullough and Hoyt2002), or on research into selected personality traits and marital forgiveness (e.g. Braithwaite et al., Reference Braithwaite, Mitchell, Selby and Fincham2016). Thus, personality-related forgiveness in marriage should be given more empirical attention. Moreover, it appears to be the case that no study has investigated the personality–marital forgiveness link in long-term marriages in the context of spouses’ satisfaction.

The aim of this study was to indicate the mediating role of forgiveness in the relationship between personality traits and marital satisfaction in older individuals. The main research problem was formulated in the following question:

• Does forgiveness mediate the relationships between individual personality traits (neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, conscientiousness) and the satisfaction of marriage in people during late adulthood?

Method

Participants

The study involved 315 people (156 women and 159 men) aged 60–75 years. In the group of women, the mean age was 64.94 (standard deviation (SD) = 4.77), while in the group of men the mean age was 66.46 (SD = 5.24). All of the participants were married. The most numerous group of respondents were in a marriage between 25 and 50 years. The mean duration of marriage was 40.64 years (SD = 7.45). Research was carried out in various regions of Poland. Among the respondents, the most numerous groups were inhabitants of medium (28.9%) and large cities (30.5%). In terms of the level of education, the most represented sample included persons with secondary (41%) and higher education (28.6%). In the subjective assessment of health, over half of the respondents (54.6%) assessed it as good. All participants were Roman Catholics. Table 1 presents more detailed data.

Table 1. The participants’ social characteristics

Procedure

The research was carried out in the form of a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. Due to the intimate nature of the psychological variables considered in the study – personality traits, forgiveness, marital satisfaction – special attention was paid to the research procedure. Therefore, the research was individual and anonymous. In order to implement the project, a set of tools was prepared, which contained: (a) a general instruction explaining the purpose of the study and containing tips on how to complete the questionnaires; (b) a personal questionnaire containing questions related to demographic parameters and subjective assessment of personal health; and (c) three research methods to measure the variables included in the study.

Each respondent was acquainted with the research procedure and informed that the research is voluntary and performed for the research project. Then they received an envelope with a set of research tools, which was to be returned after filling in. In case of questions, the researcher explained possible doubts related to the nature of the research or the way of filling in the questionnaires. In total, 369 test packages were distributed. A total of 336 completed sets of questionnaires were received back. The final analysis included 315 questionnaires, which was due to the fact that 21 sets were incomplete or filled in incorrectly.

Since there is no survey frame that would allow us to reach potential respondents with such efficiency in any other way, we decided to use non-probabilistic sampling – snowball sampling (Babbie, Reference Babbie2020). The research method adopted by us allows for a greater sense of anonymity of the respondents, which in turn makes it easier to raise sensitive or intimate issues in the questions (and these are undoubtedly encountered in the research on the quality of the marital relationship). It is also an effective tool for reaching the population and groups of the so-called difficult to grasp, including older spouses.

The applied research procedure received a positive opinion from the Ethical Committee at the Institute of Psychology of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin.

Measures

Personality traits

To characterise the personality of the people surveyed, the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) by McCrae and Costa (Reference McCrae and Costa1989) in the Polish adaptation of Zawadzki et al. (Reference Zawadzki, Strelau, Szczepaniak and Śliwińska1998) was used. This questionnaire is used to diagnose personality traits contained in the Big Five model. It includes 60 statements, the validity of which (in relation to oneself) is assessed on a five-point scale (from ‘I totally disagree’ to ‘I totally agree’). They relate to five personality factors (scales): neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness. The tool has high internal compatibility ratios (Cronbach's α) ranging from 0.81 to 0.86 for the main scales.

Marital satisfaction

The Marital Satisfaction Questionnaire for Older Persons (MSQFOP) by Haynes et al. (Reference Haynes, Floyd, Lemsky, Rogers, Winemiller, Heilman, Werle, Murphy and Cardone1992) is a tool for measuring satisfaction with marriage. The scale is intended for examining spouses in late adulthood. The original version of MSQFOP consists of 24 statements, of which the first 20 items are diagnostic and allow the measurement of three dimensions of marriage satisfaction: (a) communication-companionship, (b) sex-affection and (c) health. The whole scale reliability calculated using the Cronbach's α index is α = 0.96. This present study uses the Polish version of the MSQFOP scale translated by Brudek (Reference Brudek2015). The index of internal consistency (Cronbach's α) calculated for the entire scale (20 items) obtained the value α = 0.94.

Forgiveness

Characteristics of forgiveness within a marital relationship were made using the Marital Offence-Specific Forgiveness Scale (MOFS) prepared by Paleari et al. (Reference Paleari, Regalia and Fincham2009). This scale is used to measure the phenomenon of forgiveness occurring in a marriage dyad and concerning a specific offence on the part of husband or wife. It allows forgiveness to be described within two interrelated aspects, such as benevolence and resentment-avoidance. In this research project, the Polish version of the scale was used in the translation and adaptation of Brudek and Steuden (Reference Brudek and Steuden2015). The values of Cronbach's α for the benevolence and resentment-avoidance dimensions were α = 0.72 and α = 0.87, respectively.

Statistical analyses

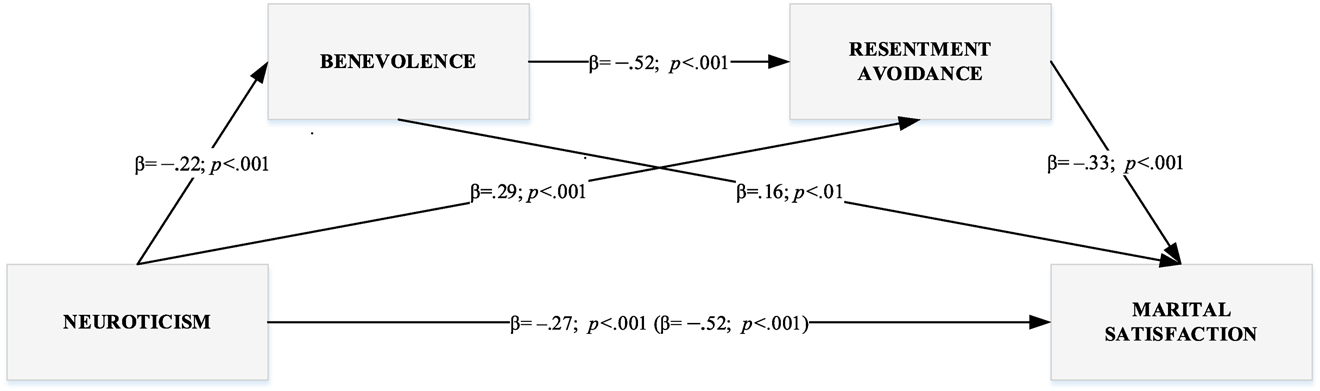

In order to assess the mediation role of forgiveness in relation to personality traits and marriage satisfaction, the PROCESS procedure for IBM SPSS Statistics version 22.00 was used. This procedure allows testing of up to 73 models of moderation, mediation or moderated mediation (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). As part of this research project, the so-called Model 6 – multiple mediation model – with two mediators was used. In the tested model, benevolence (M1) and resentment-avoidance (M2) have the character of sequential intermediary variables (mediators) in the impact of personality on the satisfaction with marriage (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Model of the direct and indirect effect of personality traits on marital satisfaction through dimensions of forgiveness.

To estimate the indirect effects, a Bootstrapping 10,000 technique with corrected confidence intervals (95% CI) was used. According to the recommendations in the methodological literature, the effects of mediation were considered significant only when the values of the average estimate of indirect ‘impact’ were in the 95% CI, so that this range did not include zero (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).

Results

The first stage of statistical calculations was the analysis of relationships in the field of analysed variables. The results of the correlation analysis revealed the existence of statistically significant correlations between the overall marriage satisfaction rate and four out of five personality traits. The highest values of coefficients (Pearson's r) were recorded in the case of neuroticism (−0.44; p ⩽ 0.001) and conscientiousness (0.32; p ⩽ 0.001), and the lowest in relation to agreeableness and extraversion (0.29; p ⩽ 0.001). Openness to experience was not statistically significantly associated with marriage satisfaction (−0.02; p = 0.389). In addition, it was noted that personality traits are related to the analysed dimensions of forgiveness. Resentment avoidance was mostly correlated with neuroticism (0.41; p ⩽ 0.001), while benevolence mostly correlated with agreeableness (0.34; p ⩽ 0.001). It was also found that the quality of the seniors’ relationship was positively associated with benevolence (0.42; p ⩽ 0.001) while negatively with resentment avoidance (−0.54; p ⩽ 0.001). Both in the first and in the second case the strength of the relationship was moderate. Table 2 presents more detailed data.

Table 2. Zero-order correlations among the wisdom, age and predictor variables

Significance levels: ** p < 0.01 (one-tailed), ns: not significant (p > 0.05).

Next, the status of forgiveness as a mediator in personality and marriage satisfaction relationships was tested. Taking into account the results of correlation analysis, the calculations were made separately for four out of five personality traits. Due to the lack of statistically significant relationships between openness to experience and satisfaction with marriage and forgiveness, this variable was excluded from further mediation analyses. In total, four models were tested.

In the first model (Figure 2), the mediating role of dimensions of marital forgiveness was tested in the neuroticism (N)–marital satisfaction (MS) relationship. Examining the indirect, sequential pathway of N's influence on MS through benevolence (B) and resentment avoidance (RA) at the same time showed that it reached the level of statistical significance (a1d21b2 = −0.04; standard error (SE) = 0.013; 95% bootstrap CI = −0.069, −0.018). This means that high N reduces readiness for kindness, which in turn reduces the desire to retaliate for harm, which reduces satisfaction with marriage. Analysing the indirect effects for individual mediators separately, statistically significant effects of the effect of N on MS were also found in the case of B (a2b2 = −0.036; SE = 0.017; 95% bootstrap CI = −0.077, −0.010) and RA (a3b3 = −0.10; SE = 0.025; 95% bootstrap CI = −0.151, −0.055). Path factors suggest that the high intensity of N, on the one hand, is not conducive to taking a friendly and amicable attitude towards the spouse but, on the other hand, it increases the tendency to revenge for the harm suffered. In the first case, the final impact on MS is positive, while in the second, negative.

Figure 2. Model of the direct and indirect effect of neuroticism on marital satisfaction through dimensions of forgiveness.

At a later stage of statistical analysis, the mediating role of forgiveness in the relationship between extraversion (E) and MS was examined (Figure 3). Mediation analysis revealed the significance of all three indirect effects through which intensity E determines the level of MS. The first is through the B process, the second through B and RA simultaneously, and the third only through RA. The first indirect effect is described by two paths: positive dependence of B on E and positive relationship of B with MS. The indirect effect parameter is positive (a1b1 = 0.025; SE = 0.013; 95% bootstrap CI = 0.005, 0.060). Thus, the greater the ability to experience positive emotions strengthens B, which in turn positively affects the quality of the marital relationship. The second method of conditioning marital satisfaction by E strengthens the willingness to forgive, which in turn reduces the tendency to avoid the perpetrator of harm, which negatively affects MS. The indirect effect is also positive in this case (a1d21b2 = 0.042; SE = 0.015; 95% bootstrap CI = 0.017, 0.076). The third indirect effect of E on MS is only through RA (a2b2 = 0.046; SE = 0.021; 95% bootstrap CI = 0.009, 0.09). Both the path factor value from the independent variable (E) to the mediator (RA) and the mediator to the dependent variable (MS) is negative. It can therefore be concluded that with the increase in E, the desire to resent a spouse decreases, which enhances the satisfaction with the relationship.

Figure 3. Model of the direct and indirect effect of extraversion on marital satisfaction through dimensions of forgiveness.

At the next stage, the mediating role of forgiveness was studied in the relationship between agreeableness (A) and MS (Figure 4). The analysis of the indirect path of A's impact on MS through two dimensions of forgiveness taken together turned out to be statistically significant (a1d21b2 = 0.073; SE = 0.018; 95% bootstrap CI = 0.044, 0.116). This means that as the positive attitude towards other people increases, benevolence increases as well, which in turn lowers the desire for revenge, which increases MS. Analysing the indirect effects for individual mediators, however, statistically significant indirect effects of A on MS were found both in relation to B (a1b1 = 0.048; SE = 0.021; 95% bootstrap CI = 0.013, 0.096) and RA (a2b2) = 0.10; SE = 0.026; 95% bootstrap CI = 0.05, 0.154). The obtained pattern of results suggests that a confident and concessive attitude towards other people (paths a1 and a2) promotes readiness for kindness and significantly reduces the tendency to nurture resentment towards a spouse, which translates into increased satisfaction with marriage (paths b1 and b2).

Figure 4. Model of the direct and indirect effect of agreeableness on marital satisfaction through dimensions of forgiveness.

The last model (Figure 5), in which indirect effects were identified, was the model of the impact of conscientiousness (C) on MS through two dimensions of forgiveness – B and RA. Testing first the indirect, sequential pathway of C's impact on MS via B (M1) and RA (M2) showed that it is statistically significant (a1d21b2 = 0.073; SE = 0.021; bootstrap CI = 0.04, 0.122). While analysing the indirect effects for individual mediators separately, no significant effects of C on MS were found for both B and RA. Based on these results, it can be assumed that as the degree of organisation, perseverance and motivation in goal-oriented activities increases, the readiness for B also increases, reducing the tendency to remember the harm enhances relationship satisfaction.

Figure 5. Model of the direct and indirect effect of conscientiousness on marital satisfaction through dimensions of forgiveness.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to understand better the associations between personality domains, forgiveness towards a spouse and marital satisfaction in older long-term married individuals. The mediating role of forgiveness on the relationships between personality and satisfaction with marriage was explored.

Analyses revealed that marital forgiveness mediated the negative relationship between individuals’ neuroticism and quality of their marriage. Those who are higher in neuroticism are less likely to forgive their spouses and this lack of forgiveness leads to poorer relationship satisfaction. Results from this research are consistent with the study on trait forgiveness which partially mediated the effect of neuroticism on relationship satisfaction in committed romantic relationships (Braithwaite et al., Reference Braithwaite, Mitchell, Selby and Fincham2016). After being hurt by a partner on the occasion of disagreement, disappointment or perceived betrayal, an individual, especially a neurotic one, may react with strong negative emotions and fall into a destructive mode of interaction, like taking revenge by criticising the spouse in harsh ways, keeping him or her at a distance, making generalised negative attributions, and engaging in non-productive cycles of demand–withdraw behaviours (Gordon and Baucom, Reference Gordon and Baucom1998; Worthington and Wade, Reference Worthington and Wade1999; Bloch et al., Reference Bloch, Haase and Levenson2014, Tan et al., Reference Tan, Jarnecke and South2017). Such actions lead to further discord between spouses. As neuroticism has been perceived as a barrier in the process of forgiving, neurotic individuals are ineffective in breaking the vicious cycle of negative events and in preventing marital dissatisfaction. The mechanism may be of particular importance in older adults as their neuroticism is a key trait that has been tied to responses to everyday and health problems. As older neurotic individuals report more than emotional stable persons severe physical symptoms, elevated negative affect and a higher number of problems in daily life (Lay and Hoppmann, Reference Lay and Hoppmann2014), they are less able to use adaptive coping strategies (O'Brien and DeLongis, Reference O'Brien and DeLongis1996). These all might obstruct pro-social motivation and behaviour (including forgiveness), that leads to increased marital dissatisfaction.

The positive association between extraversion and marital satisfaction was also mediated by forgiveness towards a spouse. Results showed that the more extraverted individuals are, the more benevolence and less resentment and avoidance they present, which in turn is related to greater marital happiness. As they tend to experience positive emotions, they are more willing to evoke benevolent feelings and thoughts, and reduce resentment towards a partner even after a transgression. The link may be even stronger for older rather than other age cohorts because according to gerotranscendence theory (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005), the high quality of relationships and maximising positive emotions become more important as we age. Older extravert individuals may more strongly strive to repair damage and resolve the conflict through positive strategies for dealing with a transgression, like forgiveness and constructive communication, which in turn is connected with marital satisfaction (Bloch et al., Reference Bloch, Haase and Levenson2014; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Jarnecke and South2017). This project's findings are consistent with the results showing that older people's general satisfaction with life is related to the positive dimension of tendency to forgive, not with mere overcoming unforgiveness (Kaleta and Mróz, Reference Kaleta and Mróz2018).

Forgiveness toward a spouse mediated a positive relationship between individuals’ agreeableness and the quality of their marriage. Those higher in agreeableness were more likely to forgive their spouses which accounted for greater relationship satisfaction. This project's results are consistent with previous findings showing associations between agreeableness and marital satisfaction (Claxton et al., Reference Claxton, O'Rourke, Smith and DeLongis2012), and between agreeableness and forgiveness (Brown, Reference Brown2003; Koutsos et al., Reference Koutsos, Wertheim and Kornblum2008; Rey and Extremera, Reference Rey and Extremera2016). However, the relationships between variables have not always been as clear as in this current study (Karney and Bradbury, Reference Karney and Bradbury1995). Again the links might be stronger for ageing people. Agreeable individuals are generally predisposed to maintain more positive interpersonal relations with others, but as people age, they exit full-time employment, reduce social contacts and increase interactions with their husband or wife (Carr et al., Reference Carr, Freedman, Cornman and Schwarz2014). Thus, they might be especially interested in keeping harmony within their marriage, because they spend more time with a spouse and they are focused on marital interactions. Though disagreements and hurtful behaviours are inevitable in marriage, agreeable individuals, who might become even less egocentric and more altruistic in the process of gerotranscendence (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam1989), achieve better marital satisfaction through greater benevolence and reduced resentment. Forgiveness turned out also to mediate positive associations between conscientiousness and marital satisfaction. We found that those who are higher in conscientiousness are more likely to forgive their spouses, which in turn is related to relationship satisfaction. In previous studies conscientiousness has been rarely connected to episodic forgiveness (only with the dimension of motivation to take revenge; Rey and Extremera, Reference Rey and Extremera2014, Reference Rey and Extremera2016), and slightly more often to the tendency to forgive (Berry et al., Reference Berry, Worthington, Parrott, O'Connor and Wade2001; Kamat et al., Reference Kamat, Jones and Row2006; Balliet, Reference Balliet2010). However, older adults are usually more conscientious (Allemand et al., Reference Allemand, Zimprich and Hendriks2008) and more forgiving than middle-aged and younger adults (Kaleta and Mróz, Reference Kaleta and Mróz2018). Thus, the link between them is more likely when people age. Moreover, staying in a stable long-term marriage means that the spouses have dealt with multiple problems, both relational and external. This required being more responsible, reliable, organised and efficient, thus being more conscientious. Our long-married respondents might be higher in conscientiousness and gerotranscendence, so they prefer to behave ethically (Costa and McCrae, Reference Costa and McCrae1995) and act wisely (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam1989), including to forgive the offending partner.

Our results might be employed in counselling older adults (Blando, Reference Blando2014; Fullen, Reference Fullen2016). As forgiveness of a spouse is a mechanism via which personality traits may affect marital satisfaction, it is important for older partners to practise forgiveness on a daily basis. On one hand, forgiveness could be a buffer against the negative impact of neuroticism on marital happiness, on the other hand, it might allow positive aspects of extraverted, agreeable and conscientious tendencies to be transferred into marriage. Professionals may help older people be aware of the importance of forgiveness for creating a high-quality relationship with a spouse, which is even more important than in previous lifestages (Tornstam, Reference Tornstam2005). Counsellors might initiate discussion about forgiveness, particularly about the role of letting go of resentment and evoking benevolence, and older individals’ experience of granting and receiving forgiveness, as well as different strategies to achieve forgiveness (Aalgaard et al., Reference Aalgaard, Bolen and Nugent2016). Such interventions might be useful in strengthening motivation for forgiveness in everyday marital life.

Limitations

Apart from presenting some cognitively valuable results, it is recognised that this research project also has some limitations. Caution needs to be exercised with regard to making any generalisations from the results obtained. First of all, although it has been shown that selected dimensions of forgiveness mediate in relationships between personality traits and satisfaction within marriage in older spouses, the use of statistical analyses focused on evaluating mediation using SPSS PROCESS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013) does not allow establishment of causality. There is a need to conduct longitudinal studies on the mediating role of forgiveness in relationships of personality traits and satisfaction with marriage in late adulthood. Secondly, only religious persons were tested, which seems to be another limitation of the presented study. Readiness to forgive is strongly associated with religiosity. Including a comparative group with non-religious people would provide stronger evidence for the hypothesis being tested, or reveal that the presented mediation effect only occurs in religious persons. Finally, the study was conducted in Poland, where the Roman Catholic denomination dominates, hence it can only be generalised to other populations with some caution. It would be worthwhile to replicate research in other countries and include followers of other religions.

Summing up, despite the several limitations, our study offers interesting findings and their implications. We found that neuroticism was negatively related to forgiveness and marital satisfaction, whereas extraversion, agreeableness and conscientiousness positively correlated with forgiveness and satisfaction in ageing persons. The results also showed that forgiveness of a spouse mediates the relationship between personality and marriage satisfaction in late adulthood. Using forgiveness on a daily basis could help older adults reduce the negative impact of neuroticism on marriage and increase the positive effect of other personality traits on relationship satisfaction.

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.