THE TRANS-SAHARAN GOLD TRADE

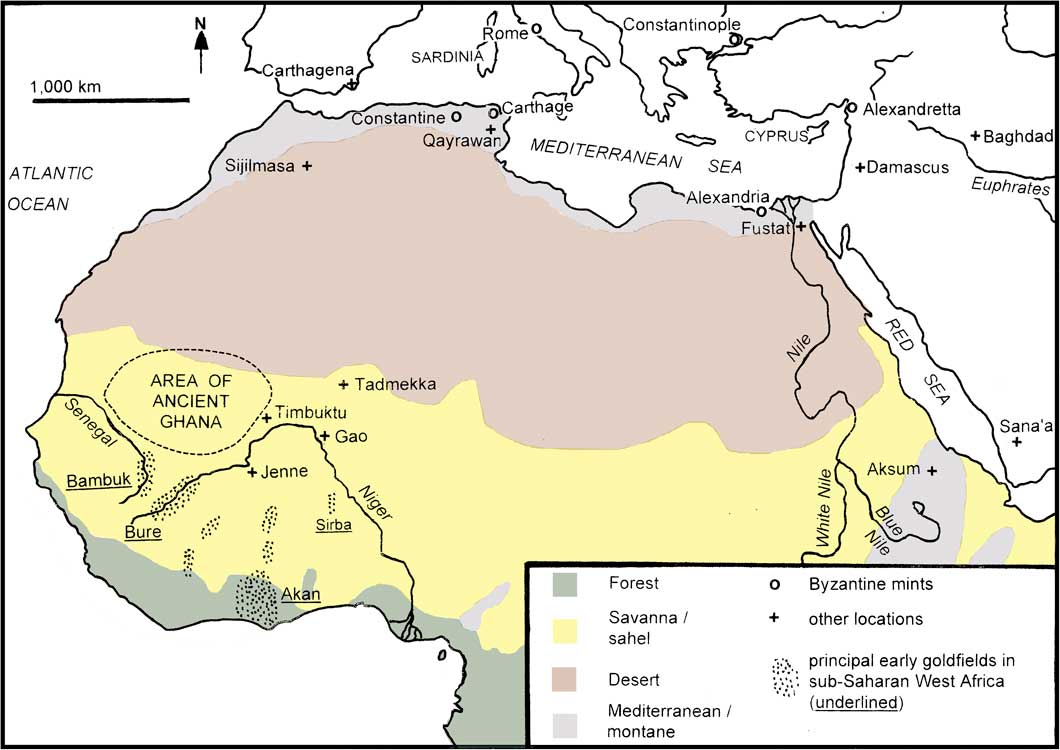

Rich gold deposits in sub-Saharan West Africa have been exploited by indigenous peoples for many centuries.Footnote 1 Since at least one thousand years ago, some of this gold has been exported to the circum-Mediterranean world (see fig 1) where it has been widely used for coinage and other purposes. The earliest written records of this trade occur in Arabic textsFootnote 2 produced long after the IslamicFootnote 3 conquest of North Africa at the end of the seventh century ad (late first century ah);Footnote 4 they refer to overland transport, but do not indicate when that practice began. Documentary sources, however, clearly show that by the ninth/tenth century it had intensified and achieved significant regularity. Not until the fifteenth century did Europeans establish a sea-route to West Africa and gain control over northward conveyance of the region’s gold. Although this outline is widely accepted, there is little consensus about the details, particularly for the earlier periods. Reliance on Arabic texts has led many scholars to assume that the trans-Saharan gold trade arose during Islamic times. Consequently, the search for numismatic evidence has been largely restricted to the study of Umayyad and Abbasid dinars.Footnote 5

Fig 1 Map of North and West Africa, the Mediterranean basin and the Middle East, showing principal locations mentioned in the text. For Africa only, simplified present-day vegetation patterns are indicated. Map: the author, with the advice and assistance of Charlotte Fox and the late Brian Foxley.

West African production of gold may probably be traced back to the middle centuries of the first millennium, but primary archaeological evidence is sparse and inconclusive. The principal regions where indigenous exploitation seems to have taken place have been mapped by several scholars.Footnote 6 They include the Bambuhu (Bambuk), Konkadugu and Gangara (Wangara) areas at the headwaters of the Niger and Senegal rivers,Footnote 7 both of which have auriferous sediments further downstream. The Sirba tributary of the Niger may likewise have been significant. Much of the gold has been recovered from alluvia and other secondary deposits, exploitation of which has left little permanent record.Footnote 8 In most cases, the quartz pipes from which the alluvial gold was ultimately derived have long ago been destroyed by erosion. There has been remarkably little detailed metallurgical or technological study of locally produced gold artefacts, few of which come from recorded and datable archaeological contexts.Footnote 9

Several factors have contributed to the prevailing dearth of information. Much West African gold occurs in areas that are not easily reached by outsiders. Those responsible for the exploitation of the deposits and/or the export of their product have been understandably reluctant to divulge details that may encourage competition. Much of the produce, if not exported, has been retained as personal wealth and/or in traditional rulers’ custody (fig 2);Footnote 10 both categories continue to be protected from scrutiny.Footnote 11

Fig 2 West African gold regalia: His Majesty The Asantehene, carried in a palanquin at the durbar held in 1999 to mark the tenth anniversary of his accession to the Golden Stool. Carrying a fly-whisk, he was surrounded by bearers of swords, the golden handles of which may be seen in the photograph. Many of his golden adornments are re-castings of those worn by his predecessors. Photograph: Gordon Frimpong, obtained through the good offices of Professor Malcolm McLeod.

The initial date for the northward transport of West African gold across the Sahara has long been a matter of controversy.Footnote 12 Evidence that it began prior to the establishment of Arab rule has generally been accorded little weight,Footnote 13 and it is salutary to speculate why this should have been so. As noted above, a prime source of information has been Arabic writings of travellers and historians from the ninth century ad (third century ah) onwards.Footnote 14 Relatively few of these writings were based on first-hand observation, although, as noted below, there are indications that some of them may incorporate material that originated well prior to the compilations in which they are preserved.Footnote 15 Interest in the pre-Islamic past has not been a general feature of Arabic culture and is still often discouraged in that context.

A trans-Saharan gold trade was certainly under way from the ninth century ad onwards, but indications that it may have begun earlier remain inconclusive. Arabic records cannot be expected to throw significant or trustworthy light on the possibility of its existence in pre-Islamic times, although a statement by al-Fazari,Footnote 16 writing at Baghdad late in the second century ah, has been interpreted as indicating that the Ghana kingdom and – by implication – outsiders’ knowledge of its wealth in gold began before Arab contact was established.Footnote 17 Writing c 320 ah, al-Hamdani, a native of Yemen known to have travelled widely in the Arabian peninsula and in Iraq but not farther afield, recorded a statement by the master of the mint at Sana’a that ‘the richest gold mine on earth [was] that of Ghana’.Footnote 18 More than a century later, the wealth of Awdaghast in Ghana was confirmed by al-Bakri,Footnote 19 albeit from second-hand report.

Al-Bakri’s compilation, prepared c 1068 (c 446 ah) but including material from earlier sources, noted that, at Tadmekka,Footnote 20 ‘their dinars are called “bald” because they are of pure gold without any stamp’,Footnote 21 and at SijilmasaFootnote 22 ‘gold … is bought or sold … by number, not by weight, whereas leeks … are sold by weight, not number’.Footnote 23 Textual evidence thus suggests that, by the eleventh century, gold represented a medium of exchange in the sudanic belt of West Africa;Footnote 24 at least in some places it circulated in pieces of standardised weight, although these bore no stamped markings such as would have transformed them into true coins.Footnote 25

An anonymous contemporary of al-Bakri recorded a second-hand account that a merchant annually despatched from Tadmekka, to an unspecified destination, a consignment of sixteen leather bags, each containing 500 ‘dinars’.Footnote 26 The weight of such a consignment, at 4.5g per ‘dinar’, would have amounted to c 2.25kg per bag, or about 36kg in total – only part of a single camel-load.Footnote 27 It appears that none of these ‘bald coins’, which circulated locally but were also transported elsewhere, has survived.

In this context, the writings of Timothy GarrardFootnote 28 have not always received the consideration that they deserve.Footnote 29 Garrard (1943–2007), who was Senior State Attorney for the Republic of Ghana, balanced evidence from a wider range of sources than more focused scholars were able to consider: textual, oral, numismatic, ethnographic and archaeological, from African, Arabic and Graeco-Roman contexts.Footnote 30 Particular attention is due to his conclusionFootnote 31 that the weight-standard employed in many West African regions for the measurement of gold dust was ultimately based on the late Roman/Byzantine unit of 4.5g, which, as will be shown below, was precisely the weight of the sixth/seventh-century gold coins called solidi. By the end of the seventh century, the weight of the solidus had widely been reduced to c 4.25g, and it was at this level that the standard was adopted by Arabs as that of their own gold currency-unit, the dinar. Thus, the evidence of weight-standards, like the archaeological record, provides no conclusive indication that gold-production in sub-Saharan West Africa began in pre-Islamic times.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE FROM TADMEKKA, MALI

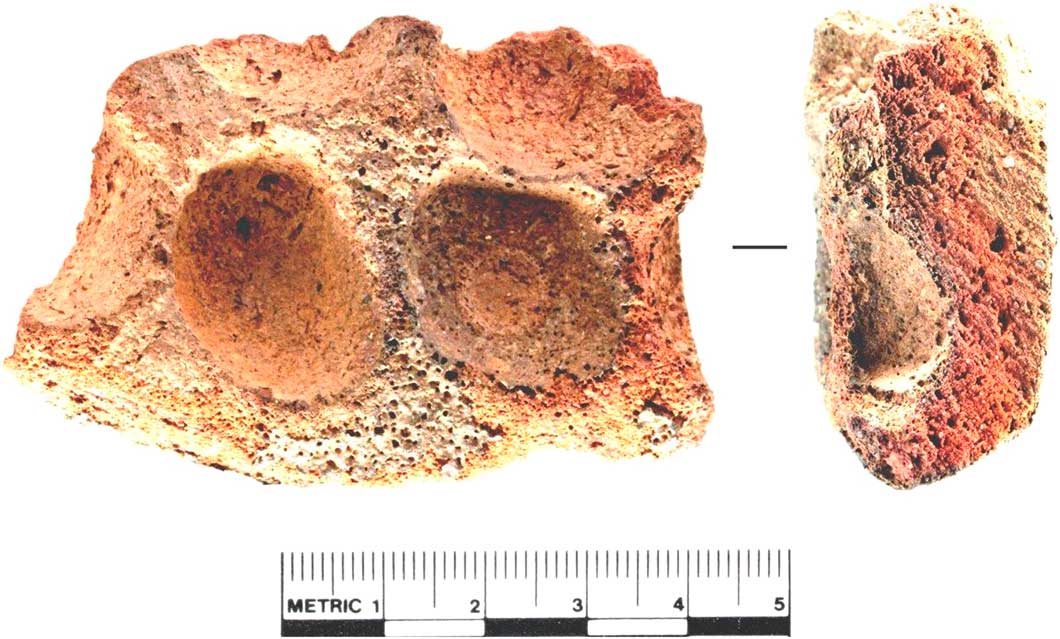

Excavations at this site in 2005 by Dr Sam Nixon have been noted above. Clay objects recovered were described as ‘coin-moulds’, it being argued that they had been used to produce standardised weight lumps of gold.Footnote 32

The so-called ‘coin-moulds’ (actually, it is proposed below, moulds for producing the metal blanks from which coins were subsequently produced) were excavated from horizon 6 in unit EKA. Nixon attributed this horizon to his period 2, for which radiocarbon dates suggest an age between the mid-eighth century and the mid-tenth.Footnote 33 Three mould-fragments (fig 3)Footnote 34 were recognised at Tadmekka, being slabs of porous low-fired clay with sub-conical depressions that averaged some 10mm deep and 20mm wide at the top. They were found associated with additional evidence for the working of metal, including gold of remarkable fineness, over a prolonged period. The dating, while undoubtedly broadly correct, will – it is hoped – be subject to refinement in future.Footnote 35 Nixon argued that the products of these moulds served as ‘coins’, but this is a misleading use of the word, following Pory’s sixteenth-century translation of Leo Africanus’ Italian text;Footnote 36 in current usage, a true coin is a piece of metal bearing a design or other officially sanctioned mark that either guarantees its weight and fineness and/or indicates its status as legal tender.Footnote 37 There is absolutely no indication that the pieces of metal produced at Tadmekka were provided there with such designs. On the contrary, Nixon and colleagues have quoted al-Bakri’s eleventh-century Arabic account to the effect that ‘bald coins’ of gold (that is, pieces of metal bearing no designs but probably standardised in weight) circulated locally at Tadmekka;Footnote 38 similar observations were recorded in the sixteenth century by Leo Africanus at Jenne and Timbuktu.Footnote 39 Both al-Bakri and Leo strongly implied that the weights of these objects were standardised, although they bore no clear literal or symbolic indication to that effect.

Fig 3 A mould-fragment from Tadmekka: left – view, showing overall vitrification and ‘ghost’ of casting in right-hand complete cavity; right – section. In both images, the original edge of the artefact is at the bottom. Photograph: supplied by Dr Sam Nixon and reproduced with his kind permission.

It should here be noted that 4.5g of pure gold would constitute a volume – depending on temperature – between 230 and 260mm3, equivalent to a sphere between 7.6 and 7.9mm in diameter.Footnote 40 The illustrations of the Tadmekka ‘coin moulds’ (see fig 3) indicate that they would have been well-suited to the production of metal pieces of this size. At the base of one depression (on specimen EKA-95) was observed ‘a circular pattern in the vitrification, almost certainly the “ghost” of a molten coin disc’Footnote 41 (see fig 3, left). Calculations based on the published photographs indicate that this circular ‘ghost’ is approximately 8mm in diameter, which is very close indeed to the dimensions suggested above. An item from the same context as the moulds was interpreted as a fragment of a crucible; prills extracted from it contained 98 per cent gold.Footnote 42

The conclusion that these moulds were used for producing small gold sub-spheroids is not contradicted by a recent metallurgical consideration of the processes involved;Footnote 43 there is, however, no evidence to support designation of the place at Tadmekka where such processes were carried out as a ‘mint’.Footnote 44 Below, it is argued that the primary reason for the production of these gold objects, which may have begun somewhat earlier, was for long-distance transport to a distant mint where they were eventually stamped with appropriate designs and transformed into true coins, as indicated by Nixon and his colleagues.Footnote 45

It thus seems highly likely that – by at least the eighth/ninth century – uniform gold sub-spheroids were produced in quantity at Tadmekka and perhaps elsewhere in the West African sudan, and that their standardised weight was probably already at the 4.5g level. The implications of this conclusion may now be considered in the context of both Byzantine and early Islamic numismatics.

BYZANTINE COINAGE

The gold coinage of the Byzantine (East Roman) Empire was produced in huge quantities, providing some measure of stability to the financial affairs of an area that often extended far beyond Constantinople’s direct political control.Footnote 46 In contrast with the rapid fluctuations and generally poor quality of the copper issues,Footnote 47 and with the comparatively rare and intermittent issues in silver, the abundant gold coinage maintained remarkable stability in its weight and purity.Footnote 48 Its basis was the solidus, introduced in the coinage reform of ad 312 under Constantine the Great, and struck at a rate of 72 to a Roman pound (324g), each coin thus comprising 4.5g of gold.Footnote 49 Despite short-term and often local fluctuations and changes in the area(s) within which it circulated, both its weight and over-98 per cent fineness were maintained with remarkable standardisation and stability until the eleventh century.Footnote 50

Gold fractions of the solidus, the semissis (half) and tremissis (one-third), were also struck at several mints in variable quantities at different times. They are distinguishable from the solidus more readily by weight than by diameter. Until the late-seventh century, to aid their recognition, the fractional denominations employed distinctive designs:Footnote 51 the obverses, for example, usually retained the imperial portrait in profile, in contrast to the solidus where a frontal or near-facing portrait had been the norm since the early fifth century.

It is clear that production of gold coins was subject to closer centralised control and much greater care than the copper. The number of mints in operation at any one time varied considerably, but coinage production at Constantinople was usually on a much larger scale than elsewhere. Designs were in most cases decreed by a central authority, but locally produced dies could result in variation between mints in detail and style.Footnote 52 Although there were exceptions, particularly on the copper, places of mintage were rarely indicated on the coins themselves. Identification of places where gold coins were minted has thus been based largely on such factors as style and find-spot. Despite much broad agreement,Footnote 53 numerous points of controversy remain, and evaluation is often hampered by lack of detailed publication of the evidence on which attributions have been based.Footnote 54

There is considerable variation in the precision with which Byzantine coins can be dated. The regnal dates of the rulers are known from historical sources. In some cases, the rulers’ ageing was reflected in their portraits, as with the growth of Constans ii’s beard during the course of his 641–68 reign (fig 4c, d).Footnote 55 The date of mintage was rarely indicated on the coins themselves, an obvious exception being the large 40-nummi copper coins introduced in 538/9 under Justinian i.Footnote 56 Two methods were employed: the emperor’s regnal year, and the more complicated system of indictions – a fifteen-year cycle, beginning 1 September, on which elements of the Byzantine tax-system were based.Footnote 57 Fortunately for the purposes of this paper, the gold coins minted at Carthage during the period under prime consideration usually bore precise indictional dates.Footnote 58

Fig 4 Regular and globular solidi compared: a) Constantinople-minted ‘regular’ solidus (MIB 10, 4.49g) of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine, dated c 629–32; b) Carthage-minted globular solidus (MIB 85[3], 4.35g) of Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine, indiction ΙΓ=13 (624/5 or 639/40); c) Carthage-minted globular solidus (MIB cf 56, 4.47g) of Constans ii, indiction [∆]Σ=6 (647/8); d) Carthage-minted globular solidus (MIB 67[1], 4.37g) of Constans ii and Constantine iv, indiction ΙΒ=12 (653/4); e) Carthage-minted globular solidus (MIB 22[3], 4.25g) of Constantine iv, indiction Z (reversed)=7 (678/9). ‘MIB’ references are to the type numbers in Hahn Reference Hahn1981. Note that all coins illustrated in this paper are shown at exactly the same scale. Photograph: John Vessey.

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, the Latin language and Roman script were retained in Byzantine coinage inscriptions for several centuries. Gradually and inconsistently, Greek forms were adopted from the mid-seventh century. More usually, Greek letter-forms were incorporated into Latin words, perhaps indicating that die-engravers received little literate supervision. Latin numerals were usually employed for regnal years, but Greek ones for indictions.

It is with the gold solidi minted at Carthage during the seventh century that this paper is primarily concerned. The Carthage mint had commenced operation under Byzantine auspices one year after the re-conquest of its territory from former Vandal rulers in 533, during the reign of Justinian i. From the start, coins were struck in gold, silver and copper, all following the pattern that then prevailed throughout the Empire. In 539/40, the Carthage mint followed Justinian’s coinage reform. Thereafter, until the reign of Focas (602–8), the Byzantine coinage issued at Carthage followed the general pattern of that produced at the Empire’s other mints, although the gradual reduction in diameter that ultimately led to the ‘globular’ solidi discussed in the following section may be discerned as early as the reigns of Maurice (582–602) or even, it has been suggested,Footnote 59 Justinian i.

In the summer of 608, the Carthage mint broke away from Constantinopolitan control.Footnote 60 This was occasioned by the seizure of local power by the exarch of Africa, named Heraclius, who was initially careful not to be seen as presenting a direct challenge to the admittedly ineffective power exercised by Focas at the imperial capital. Shortly afterwards, support for the Carthaginian usurpation spread eastwards; by the autumn of 610 the insurrection had reached Constantinople, where Focas was deposed and executed, the Patriarch crowning Heraclius’ homonymous son as emperor. Only then did the Carthage mint revert to issuing coins with designs endorsed by the authorities at the capital. The younger Heraclius reigned alone until 613, when his son Heraclius Constantine was elevated as co-emperor.

‘GLOBULAR’ SOLIDI

Here, this paper looks at the highly distinctive series of gold coins known almost exclusively from North African find-spotsFootnote 61 and generally – if not very accurately – known in the specialist English-language literature as ‘globular’ solidi’.Footnote 62 There is virtual unanimity among numismatists that the main series was minted at Carthage between the second and the tenth decades of the seventh century; this is indicated by the distribution of recorded findsFootnote 63 and is also, as will be shown below, in accord with the period when this mint continued in operation under Byzantine control. Sixth-century solidi had been remarkably uniform in design and general appearance throughout the Empire, struck on flans between 19 and 21mm in diameter and c 0.8mm in thickness. Globular solidi, by contrast, measured between 11 and 15mm in diameter and as much as c 3.2mm thick, while maintaining with only minimally decreased precision the weight-standard followed elsewhere (table 1). The globular solidi maintained their weights, despite changes in size and configuration.

Table 1 Sixth/seventh-century Carthage-mint (CTG) solidi by decade, from Bellinger’s (Reference Bellinger1966) and Grierson’s (Reference Grierson1968) Dumbarton Oaks catalogues. The Carthage mint commenced issue of solidi in 534, and ceased to operate under Byzantine control c 695. Selected data for the Constantinople mint (CPL) are appended for comparison

Notes:*These averages each exclude one light-weight specimen (Dumbarton Oaks nos Maurice 216 and Heraclius 222.2), authenticity of which was questioned by the cataloguers. ** Thicknesses, not recorded in the Dumbarton Oaks catalogues, have been calculated by the author of this paper on the basis of volume and recorded diameter, assuming circular blanks in 98 per cent gold.

In the mid-seventh century, under Constans ii, the number of mints striking gold coins was much reduced, resulting in greater overall prominence for the Carthage issues.Footnote 64 It was at one time believed that two distinct series of solidi were minted at seventh-century Carthage: one globular and one retaining the size and fabric of earlier times, the latter being illustrated in figure 5.Footnote 65 It was likewise considered that not all globular solidi originated at Carthage, some being attributed to Constantine (formerly Cirta) in modern Algeria, and to mints in Sardinia and Sicily. More recent scholarship has questioned these assumptions, without always presenting the underlying evidence.Footnote 66 A consensus has emerged, however, and is followed in this paper, that all Carthage solidi were globular, and that all globular solidi minted before 695 were produced at Carthage.Footnote 67

Fig 5 Solidi attributed to the Carthage mint on stylistic grounds, but struck on regular flans: a) Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine (MIB 91–3, 4.39g), indiction ΙΒ=12 (623/4); b) Constans ii and Constantine IV (MIB 75, 4.34g), indiction unclear but 654–68. ‘MIB’ references are to the type numbers in Hahn (Reference Hahn1981). Note that all coins illustrated in this paper are shown at exactly the same scale. Photograph: courtesy of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham.

As noted above, the Carthage mint followed a tradition of precise dating for its gold coins, generally according to the indictional system.Footnote 68 This permits recognition of precise dates for the rapid adoption and subsequent development of globular solidi. Coins produced during the decades following the establishment of the Carthage mint under Justinian i c 533/34, and again between 567/68 and the end of the sixth century, were effectively identical in fabric to those issued elsewhere.Footnote 69 The transition to globular solidus production appears not to have been abrupt, but to have taken place gradually over a period of four or five decades from the 580s to the 620s. Until ad 610, this process was slow and hesitant, but in the following two decades it accelerated markedly. During the second and third decades of the seventh century – as table 1 indicates – the diameters of globular solidi were subject to a steady but marked reduction, reaching a mean of 11–12 mm from c 630 until c 670 before slightly increasing once again during the final quarter-century of operation by the Byzantine mint at Carthage.Footnote 70

Globular solidi were struck in the names of the following rulers:Footnote 71

-

610–41 Heraclius (see Byzantine Coinage section). From 613 he ruled jointly with his son, Heraclius Constantine, and, from 638, also with the latter’s half-brother Heraclonas.

-

641–68 Constans ii, who had been known as Constantine iii before the death of his father, Heraclius Constantine in 641. Latterly, he ruled jointly with his sons: Constantine iv from 654, and also Heraclius and Tiberius from 659.

-

668–85 Constantine iv ruled jointly with his brothers Heraclius and Tiberius until 681, when he deposed them and reigned alone.

-

685–95 Justinian ii.Footnote 72

Semisses and tremisses were only very rarely struck at Carthage during the seventh century,Footnote 73 but the few known examples shared many features with the globular solidi, approaching and occasionally even exceeding their diameters but not of course their weights. Special blanks for the fractional denominations must sometimes have been available, along with dies in appropriate designs for striking them.Footnote 74

It is now appropriate to compare globular solidi with those – here termed ‘regular’ – produced at Carthage in earlier times and at other Byzantine mints through the seventh century (see figs 4 and 6, tables 1 and 2). An essential difference concerned the blanks on which they were struck. Despite the tendency of some numismatistsFootnote 75 to use the terms interchangeably, here ‘blank’ is regarded as a generic term, with ‘flan’ referring specifically to a prepared disc with flat surfaces. The flans employed for production of regular solidi varied slightly in diameter but were remarkably standardised in weight. With occasional exceptions, they were produced in near-circular form. Despite not infrequent roughness or irregularity of the edges, their faces were remarkably flat and smooth (see, for example, fig 4a). Production at some mints could be quite careless, with significant numbers of solidi struck off-centre and with excessive or uneven pressure sometimes resulting in edge-cracks.

Fig 6 The final output of the Byzantine mint at Carthage: globular solidi struck under the first reign of Justinian ii: a) MIB 18a (4.44g), indiction ε [691/2]; b) MIB 18b (4.32g), indiction θ [695/6]. ‘MIB’ references are to the type numbers in Hahn Reference Hahn1981. Note that all coins illustrated in this paper are shown at exactly the same scale. Photograph: courtesy of the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham.

Table 2 Features of ‘regular’ and globular solidi compared

Minting of globular solidi and their fractions was markedly different. In all cases, dies were produced at a size that took account of the diameters of the blanks on which they were to be employed. Design-areas on dies for regular solidi averaged 250mm2, while those used for striking the thickest globular examples had only 40 per cent of this area (100mm2). Regular solidi were usually struck with dies slightly smaller in diameter than their flans (see, for example, fig 4a). Changes in diameter of the globular coins were, however, accompanied by closely corresponding changes in the dies, strongly suggesting that the latter items were produced at Carthage itself, where for the most part they continued the tradition of precise dating (see Byzantine Coinage section) that had been established there since the late sixth century.

In many instances, the overall designs of the globular solidi remained the same as those employed at other mints;Footnote 76 the process of producing dies must therefore have been subject to centralised direction following established practice,Footnote 77 although difficulty was clearly experienced in engraving the more complex designs – particularly those of obverses showing two portraits side-by-side – within the very much smaller area that was available on the Carthage dies. This problem evidently became unsurmountable during the later part of Heraclius’ reign, as discussed for Classes III–V in n. 76. There are no globular solidi of these types; the die-sinkers evidently recognised the impossibility of reducing the ordained designs to the diameter imposed by the globular fabric of their coins and, alone among the imperial mints, continued to follow the design that had prevailed previously.Footnote 78 The simpler designs prescribed at this time for the reverses of solidi did not present such problems, and it was presumably for this reason that the Carthage mint tended to employ reverse-dies slightly smaller than those used for the obverses (see, for example, fig 4b–e). Similar problems were encountered with the inscriptions: these are often garbled and incomplete, with some letters ill-formed. They are often difficult to read, particularly on the convex obverses where peripheral parts of the designs were weakly struck.

So far as the author is aware, little – if any – research has been undertaken on the methods employed in the production of blanks for Byzantine gold coins,Footnote 79 but this now requires brief consideration for both regular and globular solidi. The remarkably flat faces of regular-solidus flans, reflected also in the configuration of the dies,Footnote 80 are readily observed; the flans were evidently made from carefully prepared metal sheet. The cross-sections of globular solidi, by contrast, are plano-convex;Footnote 81 their reverses, like those of their regular counterparts, were essentially flat, but the obverses were in most cases convex, being evidently struck from slightly concave dies intended to accommodate the shape of the blanks. The marked but progressive changes in the diameters of globular solidi were highly uniform over time, being mirrored in those of the dies employed for striking them.

The size and configuration of the globular solidi meant that greater care had to be exercised in use of the dies, and uneven or off-centre strikes are only exceptionally encountered (see table 2).Footnote 82 Another contrast with regular solidi is that the thicker blanks employed at Carthage had rougher, granular surfaces, this distinction being clearly visible on the coins themselves, most noticeably on their obverses (figs 4b–e and 6). This feature on globular solidi, discussed in more detail in the Discussion section, is distinct from that sometimes seen on other ancient coins and attributed to the use of rusty dies.

Having outlined the ramifications of the rapid adoption at Carthage of globular solidi, it is now necessary to consider why this change took place. This is a question that has received remarkably little attention either from numismatists or from historians; most writers who mention the phenomenon at all have limited themselves to simple description. Adoption of globular solidi appears to have been independent of the revolt of the Heraclii.

Grierson’s observation that ‘at other periods in history coins have sometimes been made of an abnormal shape in the hope of checking their export, and this may have been the case here’Footnote 83 is supported neither by what is known about well-established Byzantine currency-management policiesFootnote 84 nor by the circumstances of increasing isolation at Carthage, noted below in the Discussion section. More recently, Morrisson has argued that the striking of globular solidi required very much less energy than the regular fabric necessitated,Footnote 85 but that ‘numismatists can only speculate about the reasons for this particular way of economizing’. ‘Two hypothetical reasons may be proposed: firstly, the moneyers needed, or wished, to increase productivity; and second they may have tried to decrease die-wear.’Footnote 86

A broader historical perspective, however, permits a different interpretation. Evidence has been cited above that supply of gold to Carthage may have been interrupted as early as the mid-sixth century.Footnote 87 Two significant developments that took place during the period 610–30 (coinciding precisely with the development of globular solidi) were completion of the Visigothic conquest of formerly Byzantine Spain c 625, and the inception of Arab penetration through North Africa, beginning in Egypt. Both these developments would have caused serious disruption to Carthage’s access to Byzantine-controlled sources of gold. It is postulated below that gold was brought from sudanic West Africa across the Sahara to Carthage in order to replace supplies that were no longer available. In view of the conclusions reached above in relation to the distinct blanks employed at Carthage for minting globular solidi and their fractions, further consideration of these matters in the wider context of seventh-century North Africa is postponed to the Discussion section of this paper.

COINAGE AND BYZANTINE/ARAB INTERACTION IN NORTH AFRICA

The issue of globular solidi by the Byzantine mint at Carthage gave rise to features of the region’s coinage that survived long after the local eclipse of Byzantine political authority. Shortly before the closure of the Carthage mint, it seems that a new facility was established, perhaps located (although, to this author, the published evidence seems inconclusive) in Sardinia, producing Byzantine-type solidi which, while not globular to the same extent as the Carthage issues, were nonetheless markedly thicker and correspondingly smaller in diameter than those produced elsewhere. This putative Sardinian mint seems to have ceased production late in the second decade of the eighth century.Footnote 88

Rare, but particularly interesting, gold coins were struck both in North Africa and in Spain during the period immediately following the closure of the Byzantine mint at Carthage.Footnote 89 Their designs were clearly based on those of seventh-century Byzantine issues, but the reverse representation of a cross on steps was ‘de-Christianised’ by omitting the horizontal bar or by replacing the whole upper part with a globe. Some issues replicated the earlier obverse portrayal of two rulers – Heraclius and Heraclius Constantine (613–41), or Constans ii and Constantine iv (654–68).Footnote 90 The inscriptions employed Latin letters, but were garbled: they have been ingeniously interpreted, some as abbreviated Latin translations of Islamic slogans more usually presented in Arabic, others as recording mintage in Africa or in Spain. An additional noteworthy feature of these issues is that they retain not only the thick fabric and granular surfaces of the seventh-century gold coins of Byzantine Carthage, but also the weights of the solidi and their fractional denominations semissis and tremissis – the fractions, in fact, forming a significantly larger proportion of the surviving specimens than was the case with the Carthage-mint Byzantine issues.

DISCUSSION

It is informative to view these dated developments against the broad framework of North and West African history. The establishment of a Byzantine mint at Carthage had clearly been central to Justinian’s re-incorporation of the region into his Empire following the period of Vandal control 440–533.Footnote 91 The other Byzantine mint to operate on the African continent was at Alexandria;Footnote 92 the Arab conquest of Egypt led to its eventual closure c 646.Footnote 93 To the west, in what is now Tunisia and adjacent parts of western Libya and northern Algeria, parts of the old province of Africa remained under nominal Byzantine control for half a century longer.Footnote 94 As noted above in the Byzantine Coinage section, Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–41) was the son of an exarch of Africa, based at Carthage where he had seized power. By the time of his death, however, Arab expansion westward from Egypt had isolated Carthage and its province from the rest of the Byzantine Empire other than by sea. Consolidation of that expansion resulted during the final decade of the seventh century ad (late first century ah) in the conquest of Carthage with the rest of Byzantine Africa, and the establishment of Arab rule over the territory thenceforth called Ifriqiya. The Carthage mint was closed and coin production transferred to Qayrawan/Kairouan, initially continuing – it has been suggested – employment of operatives previously engaged under Byzantine auspices.Footnote 95

The reflections of this scenario in the numismatic record are not hard to discern. During the sixth century and – in most regions of the Byzantine Empire – thereafter, the minting of gold coins was under strict central control, which required free movement of bullion for processing tax-receipts and for the frequent re-coinages that evidently took place.Footnote 96 Only exiguous local sources of gold were known in Byzantine-controlled North Africa, and the Arab conquest seriously impeded communication between Carthage and the non-African parts of the Byzantine Empire. Such difficulties may, in fact, have begun as early as the sixth century, and may be reflected in the apparent cessation of gold issues from the Carthage mint during 548–65Footnote 97 and in the slight reduction in solidus-diameters (but not weights) from the 580s.Footnote 98 After at least the third decade of the seventh century, when the last areas of Spain that had remained under Byzantine control were captured by the Visigoths,Footnote 99 the Carthage mint would have been obliged to seek a new source or sources from which gold could be imported. It is suggested here that trans-Saharan imports met this need, using gold that was cast, for export and apparently also for local circulation at Tadmekka and possibly elsewhere, into sub-spheroidal lumps or ‘dumps’Footnote 100 of a standardised weight calculated precisely to meet the needs of the Byzantine mint at Carthage.

Use of moulds made of coarse gritty clay, like those excavated at Tadmekka, would have imparted to the sub-spheroids the granular surface texture and plano-convex form noted above on the globular solidi minted at Carthage (see ‘Globular’ Solidi section).Footnote 101 A corollary to this proposal is that export of gold to the Mediterranean world may have been undertaken at the instigation of its producers or processers rather than that of the ultimate users. If confirmed, this reconstruction would require major revision to current understanding of Saharan and sub-Saharan peoples’ relationships with their ruling contemporaries in North Africa. Clarification of these arguments will require more precise dating for the Tadmekka moulds.Footnote 102

Long-distance transport across the desert, even for such a high-value commodity as gold, would have been highly dependent on the availability of the camel. There is general agreement that domestic camels were not widespread in the Sahara before the mid-first millennium ad. It seems that camels spread only slowly through North Africa from east to west, and that they were not represented in faunal assemblages from Carthage until the fifth century ad.Footnote 103

This paper presents archaeological, historical and numismatic arguments in support of a sub-Saharan source for the gold used during the seventh century ad at the Byzantine mint at Carthage for production of the coins known to numismatists as globular solidi. Further metallurgical research is needed to confirm the hypothesis and to identify more precisely what African region or regions may have yielded the gold concerned. This is far from being the first time that a plea had been made for metallurgical analyses as a means of resolving controversies about the trans-Saharan gold trade, but arguments are here presented that make such a strategy somewhat clearer.

THE WAY FORWARD: ARCHAEOMETALLURGYFootnote 104

This paper is not the first to have developed arguments that point to the development of trans-Saharan traffic in gold during the second half of the first millennium. In particular, it is suggested here that the practice may have begun as early as the late sixth century ad, and that the initial recipients of West African gold may have been Byzantine rather than Arab. How can this hypothesis be tested?

Several previous writers have argued for the potential of trace-element analysis, but attempts at implementation have not so far yielded conclusive results. Until the last two decades, studies were impeded by problems of sampling and analysis.Footnote 105 More recently, continued difficulties have involved problematic or unsuitable samples, including uncertainty about differences between gold from various West African sources, unwarranted assumptions that trans-Saharan trade was an Islamic-period innovationFootnote 106 and inadequate consideration of the likelihood that gold from many numismatic sources may have become mixed in the course of repeated re-coinages.

This paper’s focus on globular solidi indicates an avenue of enquiry that would – at least in part – be less susceptible to such constraints, while artefacts of known detailed provenance within West AfricaFootnote 107 might provide more appropriate comparanda than geological samples. Emphasis has been placedFootnote 108 on the high degree of fineness maintained throughout the period when globular solidi were minted at Carthage, suggesting that the mint utilised gold that had been obtained by cementation of ore particles mined in a placer deposit, and that similar characteristics were detected in Arab-Latin coins (see Coinage and Byzantine/Arab Interaction in North Africa section) and in North African Umayyad dinars. It has also been notedFootnote 109 that this may represent access to sources of gold in Ghana, Mali and Mauritania. None of these writers, however, has been able to cite firm metallurgical evidence linking the gold used for any North African coinage with a sub-Saharan source.

Preliminary pilot investigations, using portable X-ray fluorescence equipment, has been conducted on the coins illustrated in figure 4 of this paper and on specimens kindly made available by Dr Maria Vrij at the Barber Institute, the University of Birmingham. Although this work is still in progress, preliminary results already indicate that, at least from early in the reign of Constans ii (641–68), the gold employed for producing globular solidi was significantly distinct from that used at other Byzantine mints.Footnote 110 Multiple readings from obverses and reverses of some globular solidi reveal differences that strengthen the conclusion offered in the Discussion section, concerning the use of blanks analogous to those that would have been produced in moulds such as those excavated at Tadmekka. Further research on these and related (not exclusively numismatic) topics is planned by Professors MacDonald and Martinón-Torres.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For valued assistance, including advice, information, access to collections, comments on drafts and the provision of illustrations, I am greatly indebted to, among others, His Majesty The Asantehene, Dr Rebecca Darley, Mr Peter Donald, Ms Charlotte Fox, the late Mr Brian Foxley, Professor Ian Freestone FSA, Mr Gordon Frimpong, Dr John Giblin, Professor Kevin MacDonald FSA, Professor Marcos Martinón-Torres, Professor Malcolm McLeod, Dr Alex Metcalfe, Dr Marco Muresu, Dr Sam Nixon, Ms Kate Owen FSA, Dr Laurel Phillipson, Dr Tacye Phillipson, Mr John Vessey and Dr Maria Vrij. Versions of this paper have been presented to the Institute of Archaeology at University College London, in Toulouse at a conference of the Society of Africanist Archaeologists and to the York Fellows group of the Society of Antiquaries of London; I and this paper have benefited greatly from comments made at those meetings. Lastly, the Editor of this journal and her anonymous referees have made comments and suggestions for which I am very grateful.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- DAE

-

Deutsche Aksum-Expedition