1. Introduction

Globalisation is a complex, controversial, and highly debatable concept and its costs and benefits have been widely accepted by every country. It has significant consequences for health along with mental health.Footnote 1 Globalisation is integrated with social, economic, and political processes, such as migration, cultural, employment pressures, poverty, and social change can be a risk or protective factor for mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, suicide, homicides, substance abuse, and antisocial behaviour. Globalisation is to blame for the development of mental health issues whether or not, it nevertheless has an impact on how people with those issues are treated in the health and social care systems. Lord Richard Layard (Reference Layard2005) has estimated that mental health issues cost the economy more than poverty, even though this is a problem that is rarely listed in the list of issues related to globalisation.Footnote 2 But nowadays, the world adds to this growing debate and converts the direction into developing a global mental health strategy by following the World Health Organization (WHO), and several senior international agencies in health policy.

Mental health is known as a state of well-being that is intricately linked to social, economic, and cultural conditions, and the prevalence of mental disorders is increasing. Poverty and mental illness are mutually reinforcing, and the difference between those who receive treatment and those who do not is greater for child and adolescent disorders than for major depressive disorder or schizophrenia. Globalisation has had a significant impact on psychiatry, as an increase in cultural and ethnic diversity led to a wider range of views and ideas about mental disorders. Globalisation is a global process in which prices, products, wages, rates of interest, and profits become similar, allowing powerful groups to influence the world through their ideas driven by the economy. This is leading to increased socioeconomic differences due to migration towards the economically stronger parts of the world. In comparison, high-income countries experience higher rates of mental health problems than low- and middle-income countries. In high-income countries, migration-related mental illnesses have risen due to rising inward migration rates. However, in low and middle-income countries, socioeconomic changes and life events have raised the prevalence of mental problems.

Figure 1 represents the comparative map of world globalisation in 1970 and 2019. It has been observed that the world has now become a global village and that globalisation is increasing at every single moment time. Globalisation leads to the enforcement of international standards in the management of mental health, mental health policy, and the protection of human rights of patients with mental disorders, as well as the analysis of social capital and its impact on mental health. It has also emphasised several challenges, such as an economic, democratic, spiritual, leadership, and moral crisis, and the fact that 40,000 children die each day from malnutrition and disease.

Figure 1. Comparative map of world globalisation of 1970 and 2019.

Source: KOF Globalisation Index, Swiss Economic Institute.

Broadly, globalisation is characterised by a global process in which traditional boundaries between individuals and societies gradually lead to increases such as faster and greater technological advances, global interconnectedness, and the movement of ideas, an increase in the movement of individuals, commodities, information, money, cross-cultural amalgamation, and a better confluence of expertise and knowledge in various areas. In connection to the globalisation-health nexus, globalisation is leading to higher rates of common mental disorders, such as social isolation, marital separation, and never-married single parents. This emphasises the need for well-designed mental health systems and culturally competent mental health professional training. It is crucial to recognise mental health in their cultural contexts and recognise how they are presented differently in other cultures because the cultural expressions used to express emotional discomfort differ between countries and will continue to evolve in the global village. We should be concerned about how globalisation may affect mental health, such as increased distress caused by socioeconomic integration, disparities, and changing identities. Globalisation's awareness and understanding allow us to organise mental health policies before things become overwhelming. Countries must continuously acquire to learn new skills, changing institutions, interpersonal relationships, and ground rules. This article focuses on globalisation and its effects on mental health.

Figure 2 indicates the map of the current situation of global mental disorders and the time trend of global mental disorder for high-, middle- and low-income countries. It also shows that more than eight hundred million people are affected the mental disorder worldwide however, the trend in middle-income countries (upper and lower) is higher than the high- and low-income countries.

Figure 2. Worldwide view of mental disorders.

Source: IHME, Global Burden of Disease, Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health’ [Online Resource].

Many researchers believed that beyond GDP and the use of economic indicators, there has been increasing attention to understanding and quantifying human and social growth in recent decades (Bleys, Reference Bleys2012; Stiglitz et al., Reference Stiglitz, Fitoussi and Durand2018; Frijters et al., Reference Frijters, Clark, Krekel and Layard2020). This research is in connection with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations, such as Goal 3: Good health and well-being. Goals 10 and 11 aim to reduce inequality and make cities and communities more sustainable. Lifestyle-related and socioeconomic variables that affect morbidity, such as overweight and obesity, cigarette smoking, and alcohol use, need to be further addressed since they now threaten to offset the beneficial results gained in terms of early deaths (World Health Organization, 2018).

Mental disorders are impairments in cognitive, emotional, and behavioural functioning. According to a recent report by WHO, in general, one person in every eight people (1 out of 8) in the world lives with a mental disorder. We use the latest estimation of mental health disorders, anxiety disorder, and depressive disorder, reported in their flagship Global Burden of Disease (GBD) by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). The data source presented in this entry accordance with WHO's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). This wide description encompasses many forms, including anxiety, depression, eating disorders, drug use disorder, bipolar, and schizophrenia.

The WHO classified mental health and psychosocial wellness as essential components of health in 1978, and this topic has been covered in many UN resolutions. In 2015, mental health was included for the first time in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They contend that to significantly reduce their worldwide impact on mental health, must address the socioeconomic factors that are caused to stimulate mental health problems. Mental health needs to be highlighted as a method and goal of global development in an integrated development agenda. This was crucial since earlier international development projects, including the Millennium Development Goals, had not included mental health. Instantaneously, there is the risk that all international development initiatives and funding are focused on providing care and reducing the care gap for people with mental health disorders. So, now the question is that either increasing in globalisation including economic, social, and economic perspective may affect the mental health or not?

Many researchers argue that anxiety and depression, the two most common diagnoses of mental health disorders, are among the main causes of disability worldwide, and the number of individuals with common mental health disorders is increasing (Stansfeld et al., Reference Stansfeld, Clark, Bebbington, King, Jenkins and Hinchliffe2016; Funk and Drew, Reference Funk and Drew2017). This study examines the relationship between globalisation and mental disorders, anxiety disorder, and depressive disorder in high-, middle-, and low-income countries. WHO's World Mental Organization Report (2022) explores best practices for conducting a variety of research in different European nations, as well as the use of screening tools to detect and treat stress-related illnesses, depression, and other mental health issues (World Health Organization, 2017). Because mental health is not simply an absence of illness, it includes our psychological, emotional, and social well-being. Additionally, it influences how we respond to stress, interact with others, and make decisions. Mental health indicators include mental disorders, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders, bipolar disorder, and excessive use of drugs and alcohol. However, the question of globalisation and mental health indicators is still poorly understood.

This study is based on the following structure: Section 1 represents the introduction. Sections 2 & 3 contain the overview of the literature review and theoretical framework, respectively. Section 4 shows the data source and research methodology. Section 5 explores the empirical findings. The final Section 6 puts together the conclusions that have been based on the empirical findings.

2. Literature review

Mental health problem is not just an issue for low- or middle-income countries but they significantly affected high-income countries. World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the globe continues to treat mental illness in much the same way as before. Mental health systems and services continue to be inadequate to fulfil people's needs; mental health disorders continue to have a serious impact on people's lives. They further explained that the performance according to the action plan reveals that progress has been sluggish (World Health Organization report, 2022). Progress toward greater well-being is threatened by widening social and economic disparities, lengthy wars, violence, and public health crises. To recognise the relationship between biological, genetic, social, economic, and environmental elements that contribute to mental disorders. WHO is making a clear statement: Mental health, which has been ignored for too long, is essential for the general well-being of people, societies, and nations, and should be viewed in a new way. Earlier literature has identified that there is an urgent need to examine the range of political, social, economic, and medical issues of mental health (WHO report, 2001).

Previous studies have shown that globalisation has an impact on mental health in forms of individual and group identity and community life that interact with mental disorders, through the effect of economic inequality on mental health, and through the development and dissemination of psychiatric knowledge itself. The World Mental Health Report shows that globalisation has a drastic impact on mental health, and emerging nations have high rates of mental disorders, anxiety, depression, and distress. In this regard, the Nations for Mental Health Program (1997) enforce to development of recognition, access, and management of the global burden of mental health disorders (Kirmayer and Minas, Reference Kirmayer and Minas2000).

Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Chang and Yan2020) investigate the influence of global trade on the prevalence of depressive disorders. They revealed that, particularly in democratic nations with free media or high capital-labour ratios, a rise in the value of international commerce led to a drop in the frequency of depressive illnesses. Colantone et al. (Reference Colantone, Crino and Ogliari2019) argued that trade competition has a significant detrimental influence on a person's mental health, with greater impacts on the right tail of the distribution of mental distress discomfort. It also negatively affects other family members, such as women who experience emotional pain and paternal import competitiveness, resulting in less investment in raising children and lower self-esteem and life satisfaction in children. Lewis and Araya (Reference Lewis, Araya, Sartorius, Gaebel, López-Ibor and Maj2002) suggested that globalisation is likely to have a detrimental influence on mental health. They also demonstrated that a study on socioeconomic and gender variations in the incidence of mental disorders, depression, and anxiety is necessary.

Sari et al. (Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023) used panel data from 190 nations between 1990 and 2019 to explore the connection between globalisation and suicide rates. The results revealed that the economic, political, and social elements of globalisation had an inverted U-shaped connection, while the KOF Globalisation Index had an early positive influence. Suicide rates may have reduced with globalisation and then rose as globalisation grew, showing a U-shaped association between low-income nations and suicide rates. Welander et al. (Reference Welander, Lyttkens and Nilsson2015) explore the link between globalisation, democracy, and child health in 70 developing nations between 1970 and 2009. They concluded that globalisation lowers newborn mortality and increased democracy typically leads to better child health outcomes. Nutrition is the most crucial mediator for determining the amount of globalisation's effect on children's health. In conclusion, improved child health in developing nations is associated with both globalisation and democracy.

Ghosh et al. (Reference Ghosh, Robertson and Robitaille2016) argued that in developing counties (mostly labour-abundant countries) trade liberalisation (measure in form of trade openness and import tax rates) tends to increase criminal activities, that is, burglaries and thefts. However, for other nations (capital-abundant countries), trade liberalisation has either little or no impact at all on crime. Montazeri et al. (Reference Montazeri, Tavousi, Omidvari, Hedayati, Rostami and Hashemi2014) analysed 244 citations from English and Persian biomedical journals published up to 2012 to investigate the connection between globalisation and mental health. They indicated that there were detrimental effects on mental health, with sadness, anxiety, identity issues, and suicide being the most significant.

Piachaud (Reference Piachaud2008) argued that violent political conflict is a significant contributor to mental illness, and globalisation has altered the interactions between states, businesses, and international organisations. Political violence is monitored, prepared and prevented through public mental health interventions. Mann (Reference Mann2001) highlighted a complex relationship between the transnational and international aspects of globalisation around the global environment that force us to develop new forms of collective regulation, new combinations of states and markets, and new forms of political economy. In the case of failure, the result may be an absolute catastrophe, which would not be entirely due to violence and battle. Olzak (Reference Olzak2011) concluded that sociotechnical attributes of globalisation raise deaths from ethnic conflict and vice versa from non-ethnic conflict. Furthermore, economic, and cultural globalisation significantly increase fatalities from ethnic conflicts, while the severity of civil war is greater under corrupt regimes, evidenced by a rise in deaths from non-ethnic conflict. Pinker (Reference Pinker2011) argued that historical social changes such as the pacification process, civilising process, humanitarian and rights revolutions, and protracted eras of peace have all led to a decline in different types of violence throughout time, including homicide, rape, torture, and war.

Chisadza and Bittencourt (Reference Chisadza and Bittencourt2018) discover that greater globalisation significantly lessens conflict using panel data from 46 sub-Saharan African nations spanning the years 1970 to 2013. Furthermore, they argued that social globalisation, which is linked to historical changes, determines the outcomes, but is not important for economic and political globalisation. However, increases in international migration, trade, and informational access have an impact on social interactions, which promotes tolerance and increases the opportunity cost of conflict. Relative to interstate conflict, intrastate conflict is greatly reduced by globalisation processes.

Bezemer and Jong-A-Pin (Reference Bezemer and Jong-A-Pin2013) investigated the theoretical relationship between globalisation and ethnic violence by using the fixed-effects regression for the years 1984 to 2003. They found support that globalisation and democratisation lead to ethnic violence in sub-Saharan African countries and are not proof for a global perspective. Furthermore, they concluded that democracy and globalisation cause racial conflict when ‘market-dominant’ minorities are present. Asongu and Biekpe (Reference Asongu and Biekpe2018) examine the effect of globalisation (political, economic, social, and general globalisation) on terrorism (domestic, transnational, unclear, and overall) by using a dataset of 51 African nations from 1996 to 2011 and fixed effects technique. They concluded that uncertain terrorism is positively impacted by political, social, and general globalisation. Global socialisation has a favourable effect on global terrorism. Piatkowska (Reference Piatkowska2020) uses Emile Durkheim's theory and the Stream Analogy of Lethal Violence to evaluate the effect of poverty on suicide rates in 15 Western European nations and the US between 1993 and 2000 and concluded that infant mortality rates and relative poverty are positively correlated with suicide rates.

The globalisation-violence-health nexus has been widely discussed in the literature and mostly from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives. But only a few studies explore the relationship between globalisation and mental health. This study empirically evaluates the relationship between globalisation and mental health for high-, middle- and low-income countries and contribute to filling this gap in the literature.

3. Conceptual framework

Several kind of literature discuss the broader conceptual framework regarding globalisation-health nexus (Woodward et al., Reference Woodward, Drager, Beaglehole and Lipson2001, Reference Woodward, Drager, Beaglehole, Lipson, Drager and Vieira2002; Huynen et al., Reference Huynen, Martens and Hilderink2005; Lipson et al., Reference Lipson, Beaglehole, Woodward and Drager2009), globalisation and mental health (Bhavsar and Bhugra, Reference Bhavsar and Bhugra2008; Song Reference Song2015), globalisation and income inequality (Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Braithwaite, Bhavsar and Das-Munshi2021) and globalisation and poverty Diris et al. (Reference Diris, Vandenbroucke and Verbist2014). Based on the globalisation-health framework, very few studies specify, develop, and present a conceptual framework for globalisation-mental health.

Frameworks that connect globalisation to health in general typically place an emphasis on the numerous vertical levels of aggregation at which factors act as well as the horizontal organisation by domains like economic, social, and political (Huynen et al., Reference Huynen, Martens and Hilderink2005; Labonté and Schrecker, Reference Labonté and Schrecker2007). Little discussion was made empirically in the frameworks of globalisation and mental health in the form of mental disorder, anxiety disorder, and depressive disorder for better policy implications.

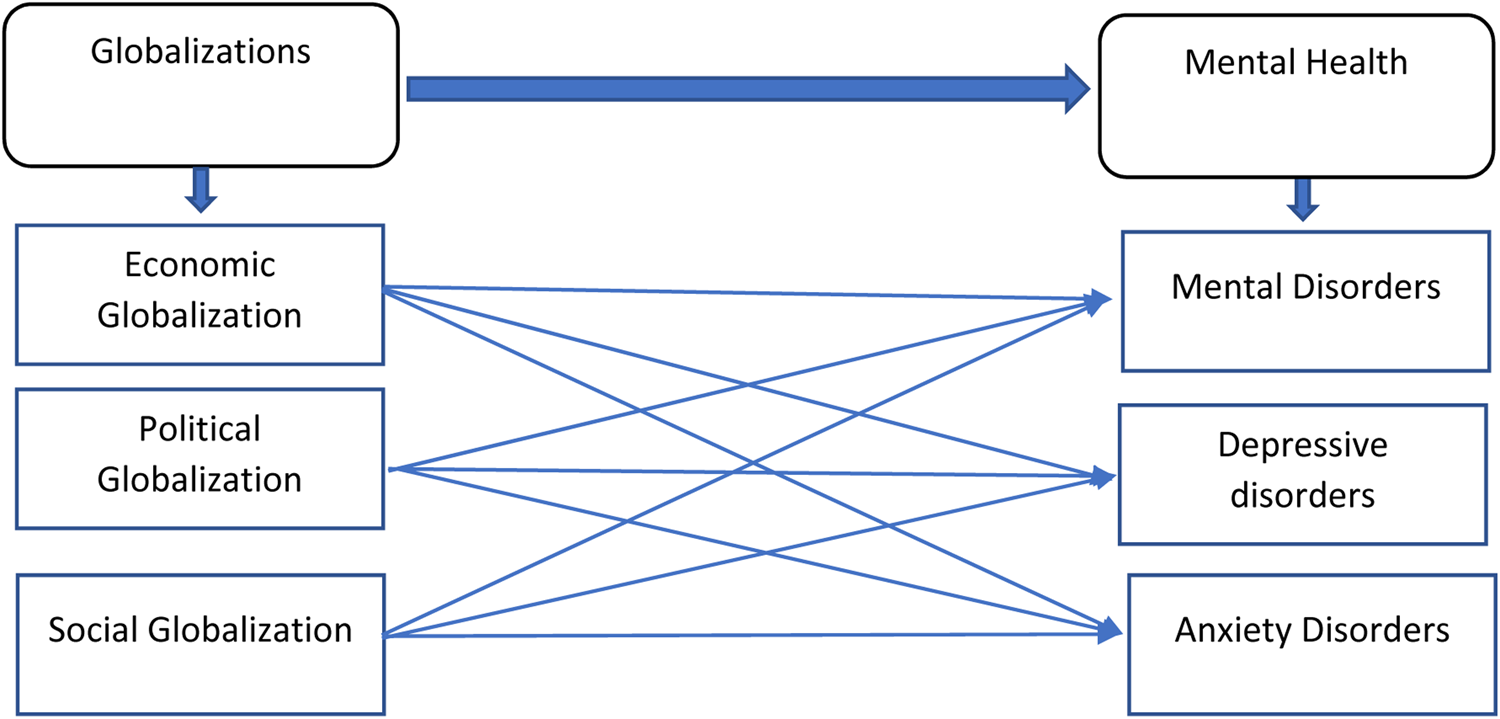

Figure 3 shows a theoretical relationship between globalisation and mental health. A theoretical framework that connects globalisation to mental health may provide for hypotheses that may be empirically tested, especially in the context of qualitative and quantitative studies. Our research aims to determine whether a conceptual framework for mental health and globalisation may produce hypotheses that can be empirically tested in the context of mental health research and policy development. The idea of doux commerce holds that trade tends to civilise people and makes them less inclined to engage in violent or illogical behaviour. It emphasises the need to better understand how globalisation affects mental health, given initiatives to expand access to mental health services globally (Patel and Prince, Reference Patel and Prince2010). Additionally, it analyses the systemic underfunding of mental health services and the asymmetrical ways in which social issues like community violence, socioeconomic inequality, and service delivery affect people with mental health issues.

Figure 3. The theoretical relationship between Globalisation and mental health. A simplified theoretical model linking globalisation and mental health. The idea of globalisation is represented by a number of connected sub-indices i.e., economic globalisation, political globalisation, and social globalisation. On the right of the diagram, we represent the main indicators related to mental health, i.e., mental disorders, anxiety, and depressive disorders. The figure is updated that was previously published in Song (Reference Song2015).

Emile Durkheim developed the notion of social integration, which describes how people interact, connect, and confirm one another within a society, in the late nineteenth century while focused on the connection between globalisation and mental health. It is a means of summarising the established social norms that govern interpersonal interactions. Durkheim summarised the disparities in social integration between pre-modern and modern communities by stating that organic solidarity holds pre-modern societies together whereas mechanical solidarity holds modern society together. The formation of social unity among human groupings is known as solidarity.

Globalisation is a multifaceted phenomenon that is closely related to several theories of mental health, including behavioural, psychodynamic, social, and cognitive theories of mental health, which explain behaviour in terms of prior experiences and driving forces. Higher mental processes including attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, and thinking are influenced by social factors, whereas behaviour is explained by prior experiences and motivating factors (Buss, Reference Buss2009). However, the globalisation process affects actions that come from innate drives, biological urges, and behavioural attributes that attempt to reconcile conflicts between one's needs and those of society. Berkman et al. (Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000) argued that social connections and affiliation have a significant impact on both physical and mental health.

A framework linking globalisation and mental health can be used to focus on the theoretical foundations of global mental health programmes and adapt them to local circumstances. Recent political developments, for instance, could portend the beginning of a new era of nationalism and provincialism (Unnithan and Whitt, Reference Unnithan and Whitt2000), presenting both crucial new difficulties and opportunities for comprehending how local and national processes interact to shape our mental health.

Figure 4 shows the understanding of different curve shapes of globalisation process as a non-linear process characterised by contrasting yet concurrent discourses and different levels of intensity and speed. Number of studies have used globalisation and quadratic globalisation relationship with suicides rates (Milner et al., Reference Milner, McClure and De Leo2012; Sari et al., Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023) carbon emission (Balsalobre-Lorente et al., Reference Balsalobre-Lorente, Driha, Shahbaz and Sinha2020; Shahbaz, Reference Shahbaz2022), financial development (Hammudeh et al., Reference Hammudeh, Sohag, Husain, Husain and Said2020), economic growth (Hammudeh et al., Reference Hammudeh, Sohag, Husain, Husain and Said2020), income inequality (Alderson and Nielsen, Reference Alderson and Nielsen2002), poverty (Agénor, Reference Agénor2004), energy consumption (Acheampong et al., Reference Acheampong, Boateng, Amponsah and Dzator2021). The process of globalisation affects social integration, mobility, and human interaction at all levels of aggregation. Globalisation and health models are used mainly for forecasting and public health strategy, but little focus has been placed on the results for mental health. It can be difficult to define globalisation, and definitions have an impact on how mental health and other aspects of health are considered.

Figure 4. U-shaped and inverted U-shaped curve relationship between globalisation and mental health.

Source: Author's design.

Since our framework enables the creation and testing of empirical issues, we recognise that globalisation frameworks frequently produce positive or negative assessments of the benefits or drawbacks of globalisation. There are certain implications for our framework. Knowledge gaps in mental health in developing nations can be conceived or understood more fully within a network of changing social and economic circumstances. Understanding mental health requires close attention to the social and political context of the community, particularly distributional equality. A theoretical framework that connects globalisation to mental health can aid in formalising and considering trade-offs that may unavoidably exist between the potential risks and advantages of suggested policies. Migrations, decreases in social mobility, and long-term disadvantages are key factors to consider when attempting to understand the lives of those who are affected by social and economic transformations in low- and middle-income countries (Bhavsar and Bhugra, Reference Bhavsar and Bhugra2008).

Consequently, we postulate the following hypothesis.

H1: Is there any curvilinear relationship existing between globalisation and mental health? (globalisation–health relationship).

Previous evidence suggests that there is a negative association between mental health and trade policies, rapid economic growth, and economic exclusion (Corrigall et al., Reference Corrigall, Plagerson, Lund and Myers2008). A growing body of research establishes a relationship between social context including local poverty, inequality, and cohesion and mental health (Evans, Reference Evans2003; Gascon et al., Reference Gascon, Triguero-Mas, Martínez, Dadvand, Forns, Plasència and Nieuwenhuijsen2015). Frameworks connecting globalisation to mental health have not yet established how globalisation is changing our physical environment (McMichael, Reference McMichael and Beaglehole2000). To conceptualisation the framework between globalisation and mental health must take into account the correlation between unemployment and indicators of worse mental health, as well as the experience of job insecurity, unfavourable working conditions, or de-unionisation if one is employed (Weich and Lewis, Reference Weich and Lewis1998; Kortum and Ertel, Reference Kortum and Ertel2003; Shaffer and Brenner, Reference Shaffer and Brenner2004; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Lee and Rodgers2007). Frameworks on globalisation and health offer a conflicted or unfavourable assessment of how it affects health, but it is necessary to properly understand specific relationships regarding mental health. There is a lack of conceptualisation in globalisation-health frameworks of how social, economic, political, and moral factors influence the types of global health data collected, their intended uses, and the definitions of abnormality used (Krieger, Reference Krieger2001).

4. Empirical model, methodology and data source

This section discusses the empirical model, methodology and data source used for empirical analysis. We used data of worldwide 201 countries including high-, middle- and low-income countries for the period 1970–2020 (for more details, see annex-1 in appendix, list of countires). However, the data of overall globalisations and sub-indices i.e., economic, political, and social globalisation is available since 1970–2020, while the data of various forms of mental health disorders, anxiety disorder and depressive disorder available from 1990–2020. Again, the data has a restriction for more detailed analysis, in particular the sample size is too small.

To explore the association quadratic form of globalisation and mental health, we develop the following empirical model as proposed by the Sari et al. (Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023) and López-Villavicencio and Pla (Reference López-Villavicencio and Pla2019) for our empirical analysis.

where MH i,t is the mental health for country i at the time t. Mental health is used the proxy of mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD) and depressive disorder (DD). Glob i,t presents the KOF globalisation index including sub-indices economic globalisation (EG), political globalisation (PG) and social globalisation (SG). Whereas $Glob_{i, t}^2$![]() is the quadratic form of globalisation index including each index with estimated separately with its quadratic form. Finally, X i,t is the set of control variables including income growth, unemployment rate, school enrolment rate and urbanisation population but φt fixed effect model control for all the potential confounding factors. The fixed effect technique is a powerful tool for panel data analysis, especially when dealing with data that exhibits individual-level heterogeneity and time-varying effects. A fixed effects model would be excellent in this scenario because it can account for unobserved countries and time-fixed effects. Data about variables description, symbols, and source can be seen in Table 1.

is the quadratic form of globalisation index including each index with estimated separately with its quadratic form. Finally, X i,t is the set of control variables including income growth, unemployment rate, school enrolment rate and urbanisation population but φt fixed effect model control for all the potential confounding factors. The fixed effect technique is a powerful tool for panel data analysis, especially when dealing with data that exhibits individual-level heterogeneity and time-varying effects. A fixed effects model would be excellent in this scenario because it can account for unobserved countries and time-fixed effects. Data about variables description, symbols, and source can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of the variables used and their expected signs in the regression

5. Empirical findings

We begin our analysis by exploring the various forms of mental health and non-linear relationship with overall globalisations (G), economic globalisations (EG), social globalisations (SG) and political globalisations (PG) at global prospective including high-, middle- and low-income countriesFootnote 3. Globalisation works as a double-edged sword; it means that it can have positive and negative consequences. Thus, it is quite interesting to examine the non-linear effect of globalisation. It is important to understand globalisation as a nonlinear process characterised by contrasting yet concurrent discourses and different levels of intensity and speed. Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics of all the dependent and independent variables used in our empirical findings. Mental health is determined through mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD), and depressive disorder (DD). Means values for MD, AD and DD are 13.38, 4.32 and 3.96, respectively. Globalisation (G) is segregated into further three main categories, i.e., political globalisation (PG), social globalisation (SG), and economic globalisation (EG) and their nonlinear (quadratic forms) also used in our empirical analysis. The means values for G, PG, SG, and EG are 49.71, 49,95, 50.08 and 49.40 and mean values of quadratic forms are 2454.8, 2875,4, 2731.9 and 2340.9, respectively. Moreover, mean values of control variables such as unemployment rate, income growth, urbanisation and school enrolment rate are 8.20, 3.69, 52.2 and 97.3, respectively. Means, median and standard deviation of all the variables indicate that the data is well organised and well-structured for empirical analysis.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Note: (a) Mental health data taken from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Global Burden of Disease, Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health’ [Online Resource]. Mental health illnesses are complicated and come in a variety of shapes and sizes, including eating disorders, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression. We used only mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD), and depressive disorder (DD) that are used mainly in literature. The underlying sources of the data used to create these definitions, generally in line with the WHO's International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) system. (b) KOF globalisation index is measure through three main categories economic globalisation (EG), political globalisation (PG) and social globalisation (SG). Since the 1970s, globalisation in these sectors has increased, with the Cold War era providing a particularly strong boost. The KOF index assigns a score of 100 to each nation; the higher the number, the more globally integrated the nation is.

Tables 3–5 show the empirical results of globalisations on mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD), and depressive disorder (DD) of the full sample dataset. All the Tables 3–5 indicate that overall globalisation (G) and the subindices, i.e., economic globalisation (EG), political globalisation (PG) and social globalisation, create a U-shaped curve relationship with mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD), and depressive disorder, respectively. Our findings show that globalisation and subindices (G, ED, PG, SG) initially decrease before increasing it for mental disorder, anxiety disorder and depressive disorder (Tables 3–5). In Tables 3–5, columns 1–4 represent the robust coefficient without incorporating control variables, while columns 5–8 represent the coefficient value by incorporating control variables. More specifically, column 1 represents the coefficient values of overall globalisation (G) and globalisation2 (G2), −0.0211 and 0.006 for mental disorders (Table 3), −0.0038 and 0.001 for anxiety disorders (Table 4) and −0.0079 and 0.0014 for depressive disorder (Table 5), respectively. However, column 5–8 represents the coefficients value by adding the control variables. In Tables 3–5, column 5 shows the coefficient value of overall globalisation and globalisation2 are −0.025 and 0.0098 for mental disorder, −0.0072 and 0.0039 for anxiety disorder, and −0.004 and 0.003 for depressive disorder, respectively. These results reveal that overall globalisation is decreasing at a certain limit for mental disorder, anxiety disorder and depressive disorder (Tables 3–5), then start to be increase by creating a U-shaped relationship between them.

Table 3. Fixed effects estimates of globalisation and sub-indices on mental disorder (MD)

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Table 4. Fixed effects estimates of globalisation and sub-indices on anxiety disorder (AD)

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Table 5. Fixed effects estimates of globalisation and sub-indices on depressive disorder (DD)

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

These results are similar for the globalisation's sub-indices i.e., economic globalisation (EG), political globalisation (PG) and social globalisation (SG) (Tables 3–5). The coefficients value of EG, PG, and SG and the squared value for mental disorder are −0.0014 and 0.0058, −0.007 and 0.0074, −0.0250 and 0.0014, respectively (Table 3, columns 6–8). The coefficient values for anxiety disorder are −0.0001 and 0.0017, −0.0055 and 0.0027, −0.0017 and 0.0026, respectively (Table 4, column 6–8), and for depressive disorder the coefficient values are −0.0043 and 0.0058, −0.0041 and 0.0053, and −0.0050 and 0.0016, respectively (Table 5, columns 6–8). These results indicate that EG, PG and SG initially decrease before increasing for mental disorder (Table 3), anxiety disorder (Table 4) and depressive disorder (Table 5). In short that sub-indices of globalisations (i.e., EG, PG, and SG) creates a U-shaped curve relationship with mental disorder (MD) and anxiety disorder (AD) and depressive disorder (DD).

Our results show that there is the lowest incidence of mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD), and depressive disorder (DD) in the middle ranges, with peaks in both the lower and upper ranges of the globalisation process. It implies that each country faces a lot of hurdles at the start of globalisation process (Low specialisation in globalisation) in form of cultural differences, language barriers, lack of funds, less technological absorption capacity that may be the reasons where globalisations create a high mental problem. However, in the middle of the globalisation process (medium specialisation in globalisation), countries can get the benefits of globalisation through easy international income payment, reduce investment restrictions, free trade agreements, regulations, treaties and taxes, foreign direct investment, portfolio investment, NGOs and international organisation and diversity. All these favourable outcomes support globalisation to reduce mental problems up to a certain point (lowest point). At the peak point of upper range (high specialisation in globalisation) negative consequences of globalisation again start, i.e., increasing completion, job displacement (jobs loss due to advance technology), unequal economic growth, increases potential global recessions, exploits cheaper labour markets, lack of local businesses that causes to increasing mental problems in long run.

In comparing to our empirical findings, Cheema et al. (Reference Cheema, Kalra and Bhugra2010) argued that more and more socio-centric societies will turn into ego-centric ones due to globalisation and this could lead to higher rates of common mental disorders. Okasha (Reference Okasha2005) demonstrates that the effects of globalisation are clearly both positive and negative and that both losers and winners are likely to be produced. Globalisation has generally been found to raise living standards, but some researchers and policy makers caution that it may also have a negative impact on local or growing economies, as well as on specific employees. If we agreed with both aspects of globalisation, Colantone et al. (Reference Colantone, Crino and Ogliari2019) found that import competition has a large negative impact on individual mental health and negative spill over to other family members. Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Chang and Yan2020) argued that trade brings about positive mental health outcomes in democracies, countries having free media, or capital-abundant economies. Sharma (Reference Sharma2016) analyses that as a consequence of globalisation, poverty and inequalities, migrations, rapid and uncontrollable sociocultural value change and identity diffusion have harmful effects on mental health and well-being. Kirmayer and Minas (Reference Kirmayer and Minas2000) argued that globalisation affect the mental health by three ways: by affecting individuals and societies collective identities, by growing economic disparities, and by influencing how psychiatric information is developed and disseminated.

In the same domain, theory of social integration anticipated that with societies modernisation leading to the development of mental health problems. It makes the supposition that societal influences may channel human hostility into various ways while still fostering it from similar root causes (Durkheim, Reference Durkheim1951; Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Abrutyn, Pescosolido and Diefendorf2021). Our results are contradict with the findings of Sari et al. (Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023) and Milner et al. (Reference Milner, McClure, Sun and De Leo2011) that show there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between globalisations and suicide rates, overall and or both for male and female. A study by Milner et al. (Reference Milner, McClure and De Leo2012) also confirmed that the regional level association between globalisation and male suicides is U-shaped for Asia and eastern Europe. However, LaFree and Jiang (Reference LaFree and Jiang2023) found an inverse relationship between globalisation and homicides. They further argued that countries with a high level of inequality with globalisation reduce homicides, while the case is more vulnerable for low-income countries with high inequality.

Corrigall et al. (Reference Corrigall, Plagerson, Lund and Myers2008) investigates the impact of global trade policy on sociostructural determinants of mental health including social inequality, mental health systems, food security, poverty, access to pharmaceuticals, alcohol consumption, and occupational health. They found strong evidence that there will probably be a considerable influence of global trade on mental health. According to the Bhavsar and Bhugra (Reference Bhavsar and Bhugra2008), globalisation is a multifaceted phenomenon. Economic change may have negative effects on mental health, but it is important to take this into account in the context of each person's identity and the culture of their local community. A comprehensive knowledge of globalisation as a diverse range of interconnected social, economic, and cultural processes should serve as the basis for any actions. It is possible that the increasing prevalence of specific mental disorders outside of the West is a result of social and cultural change.

The control variable shows that income growth (GDPG) and unemployment (UN) are significant positive associations with mental disorder and anxiety disorder and insignificant for depressive disorder. Literature shows that increasing income growth aggregate level also cause income inequality, corruption that promote the mental disorder. unemployment is the cause of losing self-esteem, less socioeconomic status, negative mood, social exclusion, schizophrenia, anxiety, and depression. Unemployment-related stress can have an adverse effect on a person's mental health, including sadness, anxiety, and low self-esteem, as well as their long-term physiological health. However, our findings are also highlighted that urbanisation and school enrolment rates may reduce (negative association) the effect of mental disorder, anxiety disorder, and depressive disorder (as shown in Tables 3–5).

Tables 6–8 represents the relationship between globalisation and mental health for high-, middle- and low-income countries. The results indicate that in high-income countries, globalisation (G) and quadratic globalisation (G2) have shown an inverted U-shaped curve relationship with mental health (For MD, AD, DD) and a U-shaped curve relationship for middle- and low-income countries. However, the coefficient values of G and G2 for high-income countries are 0.011 and −0.0002 for MD, 0.012 and −2.73E for AD, and 0.032 and −0.0002 for DD, respectively (Tables 6–8, column 1). The coefficients value of G and G2 for middle- and low-income countries are −0.029 and 0.0001, −0.067 and 0.0005 for MD (Table 6, columns 5 and 9), −0.0078 and 5.39E, −0.012 and 0.0001 for AD (Table 7, column 5 and 9) and −0.0032 and 1.92E, −0.059 and 0.0006 for DD (Table 8, column 5 and 9), respectively.

Table 6. Fixed effects estimates of globalisation and sub-indices on mental disorder (MD) in high-, middle- and low-income country groups

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Table 7. Fixed effects estimates of globalisation and sub-indices on anxiety disorder (AD) in high-, middle- and low-income country groups

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

Table 8. Fixed effects estimates of globalisation and sub-indices on depressive disorder (DD) in high-, middle- and low-income country groups

Note: Robust standard errors in parentheses, ***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.10.

We also found similar results for globalisation's sub-indices (i.e., EG, PG and SG) by showing that in high-income countries, there is an inverted U-shaped curve relationship between EG, PG and SG with mental health (i.e., MD, AD, DD) and a U-shaped relationship for middle- and low-income countries. In the case of high-income countries, Table 6 (column 2) indicates that the coefficient value of economic globalisation (EG) and economic globalisation2 (EG2) with mental disorder is 0.029 and −0.0003, while Table 7 (column 3–4) indicates that the coefficient of political globalisation (PG) and social globalisation (SG) and their quadratic forms (PG2, SG2) with anxiety disorder are 0.010 and −4.89E and 0.0168 and −0.0001, respectively. Table 8 (column 2–4) indicates that the coefficient of economic, political, and social globalisation (EG, PG, and SG) and quadratic forms (EG2, PG2, and SG2) with a depressive disorder are 0.035 and −0.0002, 0.0046 and −9.47E, and 0.017 and −0.0001, respectively.

In middle- and low-income countries, the coefficient values of EG, PG, and SG along with quadratic forms (EG2, PG2, and SG2) for the mental disorder are −0.0072 and 0.0001, −0.0066 and 2.36E, and −0.32 and 0.0002 (Table 6 column, 6–8), −0.007 and 5.56E, −0.010 and 4.46E, and −0.0526 and 0.0005 (Table 6 column, 10–12), respectively. In Table 7, the coefficient values for middle- income countries of PG and PG2 are −0.0046 and 2.58E for anxiety disorder (column 7), while the coefficient values for low-income countries of EG, PG, and SG and quadratic forms (EG2, PG2 and SG2) are −0.0090 and 0.0001, −0.0051 and 6.27E, and −0.0065 and 0.0001 (column 10–12), respectively. Table 8 indicates that coefficient values for middle-income countries of PG and SG and quadratic form (PG2, SG2) are −0.0040 and 3.30E, and −0.0096 and 8.70E, respectively (Table 8, column 7–8). In low-income countries, the coefficient of EG, PG and SG and quadratic forms (EG2, PG2 and SG2) for depressive disorder are −0.025 and 0.0003, and −0.010 and 3.66E, and −0.013 and 0.0001 (Table 8, columns 10–12), respectively.

We observed that in high income countries, there is an inverted U-shaped curve relationship exists between G and EG for mental disorder (MD), G, PG and SG for anxiety disorder (AD) and G, EG, PG, and SG for depressive disorder (DD), respectively. In support to our research findings, previous work of Sari et al. (Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023); Milner et al. (Reference Milner, McClure and De Leo2012) show that there is an inverted U-shaped curve relationship exists between the connection between political and social globalisation with suicide rates and linear positive relationship between overall globalisation and suicide rates (Milner et al., Reference Milner, McClure, Sun and De Leo2011). These results indicate that in high-income countries, globalisation process (at the medium specialisation in globalisation) faces higher mental illness but after reached up to high specialisation in globalisation it again starts to decline in mental illness.

We found that in middle- and low-income countries there is a U-shaped curve relationship between overall globalisation (G) and subindices economic globalisation (EG), political globalisation (PG), and social globalisation (SG) with mental disorder (except for EG in low-income countries), anxiety disorder (except for EG and SG for middle-income countries) and depressive disorder (except for G and EG in middle-income countries). In comparison to our findings, Sari et al. (Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023) and Milner et al. (Reference Milner, McClure and De Leo2012) found an inverted U-shaped curve relationship between globalisation and suicides for middle-, and low-income countries. Nevertheless, a U-shaped curve relationship found for low-income countries by Sari et al. (Reference Sari, Er and Demir2023) and Milner et al. (Reference Milner, McClure, Sun and De Leo2011) for Asian countries. In this connection, the World Bank (2016) reported the mapping patterns of violence and conflict in middle-income countries and argued that more people have been killed by political violence and homicides in middle-income countries than in low-income countries. Middle- and low-income countries are experiencing rapid economic, political, and social transition that have a higher burden to health behaviour and chronic disease including mental health (Dzator, Reference Dzator2013). The characteristics of good mental health are the opposite of those of poor mental health or mental illnesses, which are defined as diagnosable condition that significantly impairs a person's cognitive, emotional, and social abilities. Reification appears to have occurred sometimes, and other cultural creations, such as explanations for health beliefs or idioms for distress, were either ignored or viewed as additional layers of meaning rather than as the essential organising principles that many people appear to view them as. The rich traditions and cultural history of low- and middle-income countries may unintentionally be undermined by the naive generalisation and transfer of Western psychiatric and psychological theories to the rest of the globe.

In middle-income countries, increasing globalisation is a significant cause of increased income inequality that increase the cause of mental illness. While LaFree and Jiang (Reference LaFree and Jiang2023) argued that countries with high level of inequality with globalisation reduce the homicides although the case is more vulnerable for low-income countries with high inequality. In low-income countries, Steinbach (Reference Steinbach2019) and World Bank (2016) reported that it is commonly assumed that low-income countries are more prone to Fragility, Conflict, and Violence (FCV) than middle-income ones. However, over the past decade, more people have been killed from violence and homicides in middle and low-income countries than in high-income countries. In the last 10 years, more than twice as many people have died from such conflicts in middle-income and low-income countries than in high-income countries. Most conflicts today occur not in the world's poorest places but in low- and middle-income countries. An opposing viewpoint is that wealthy countries can learn from the prevention and management of mental health problems in low-income countries and this may help to address the remoteness of psychiatry and its allied professions from the communities they serve in many Western countries (McKenzie et al., Reference McKenzie, Patel and Araya2004).

According to Kodama et al. (Reference Kodama, Perpiñan, Spring and Harris2004), globalisation can give underprivileged organisations the ability to buy weapons at the outset of a war. As factions compete for control of natural resources, these international markets could contribute to local instability. Many view globalisation as a source of or contributing factor to conflict (Scholte, Reference Scholte1997; Sparks, Reference Sparks2005) and there are numerous case studies of the destabilising impact of economic and cultural forces, radiating from the West, on local politics and culture in places such as Iran, Sierra Leone, or Indonesia (among others). However, this is a one-sided view of globalisation and conflict, and the true relationship is more complex and subtle. When development level and regional disparities are used as controls, Tsai (Reference Tsai2007) finds that political globalisation has considerable good effects but that economic and social globalisation has little positive impact.

Over the past decade, globalisation has emerged as an important area of discourse and research, as well as a powerful impetus for the development of mental health services in low- and middle-income countries. Unfortunately, there is a misconception that global mental health is about improving care in all countries, including high, middle, and low countries, but we believe that globalisation should be about improving mental health only for high-income countries and vice versa for middle- and low-income countries. It is argued that wealthy countries, whether they have market-driven or state-planned systems, have created expensive and inefficient mental health services, and decisions about mental health do not sufficiently involve those who use services and their families (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Binagwaho, Martell and Mulley2014). Although mental healthcare systems vary greatly in richer counties in most resource-rich countries, they remain inaccessible and insensitive (Drake et al., Reference Drake, Binagwaho, Martell and Mulley2014) with the suggestion of widespread evidence of poor quality care.

6. Conclusion

This article aims to examine the relationship between globalisation and mental health using the dataset of high-, middle- and low-income countries for the period 1970–2020. Our results indicate that there is an inverted U-shaped curve relationship exist between globalisation (including its sub-indices economic, social, and political globalisation) and mental health i.e., mental disorder (MD), anxiety disorder (AD) and depressive disorder (DD). Similar findings have found for high income countries as an inverted U-shaped curve relationship between globalisation and mental health and a U-shaped curve relationship for middle- and low-income countries. Our results show that there is a lower incidence of mental health in the middle ranges, with peaks in both the lower and upper ranges of the globalisation process for high-income countries and vice versa for middle and low-income countries. Globalisation itself, the idea of everyone connecting, isn't necessarily a bad thing, but the way it's being enacted is causing problems. After examining the many aspects of globalisation and how they can affect the prevalence of mental disorders, some uncertain statements can be made about different regions of the world.

In the 21st century, globalisation (including economic, social, and political globalisation) plays a significant role in migration, and it continues to play a central role in the debate about how globalisation contributes to mental disorders today. Migration flows have always existed, but what sets migration apart today is the interconnectedness of diasporas worldwide. Globalisation is a link between the perceptions within cultures and level of economic development of what constitutes mental health, with prevalence rates of some disorders arguably increasing as middle- and low-income countries become wealthier and concurrently more exposed to the wealthy nations. In a globalised economy, urban centres grow as populations move from rural to urban spaces to better access opportunities, especially in low-income countries. In tandem with higher urbanisation, there is an increased prevalence of depression, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, and poverty, which presents a pressing mental health issue in a time of rapid social change. Researchers advocate for a public health approach where the causes of mental health problems are addressed directly, as a better alternative to increasing services.

A programme for ongoing research is needed to fully comprehend the complexity of these shifting identities and patterns of experience, both on the individual and community level, and to ensure that local contexts are not lost in the morass of bottom-line calculations. In terms of implementation of mental health policy, problems exist for every country despite the belonging to high-, middle-, and low-income countries having problems. Therefore, in the future, efforts should focus on supporting policy implementation in the context of high- middle and low-income countries in formulating mental health policies.

Acknowledgements

Author would like to thank the University of Oulu including hospital (UNIOGS) for their financial support. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests

None

Consent for publication

I Saqib Amin at the Department of Economics, Accounting and Finance, Oulu Business School, University of Oulu, Finland, hereby submitting the article ‘Globalisation and mental health: is globalisation good or bad for mental health? Testing for quadratic effects’ in ‘Health Economics, Policy and Law’ journal. This article has not been sent to any other journal for review or publication.

Availability of data and material

Data is accessible to anyone in the general public, without the need for special qualifications, permissions, or privileges.

Appendix

Annex I List of countries

List of high-income countries:

List of middle-income countries:

List of low-income countries: