Introduction

It is often observed that in modern English no political movement has created an internet jargon with the speed and range of the alt-right. Recently, however, we are seeing a specifically misogynist strand of this jargon shoot up, coming from the growing online anti-feminist network known as the Manosphere, and specifically its popularly best known outpost of ‘incels’. The neologisms being produced by incels have come to form a true cryptolect, developing at a rate that almost escapes linguistic description; at the same time, the elements of this cryptolect are quickly infiltrating broader popular culture and global vernacular contexts, from social media to Urban Dictionary (Ging, Lynn & Rosati, Reference Ging, Lynn and Rosati2020).

An obscure online subculture for some time, incels have attracted attention lately in both media and research following several misogyny-inspired murder attacks, perpetrated by young men who had associated with the community. Though hard to define as a group, incels (‘involuntarily celibates’) can be described as an online community of men who do not have sexual relationships with women, and blame women, feminism or society at large for the situation. They have taken the ‘black pill’Footnote 1 – a reference to accepting reality, in which women have power over men – and understand inceldom as a permanent condition. By now, linguists have shown that in spreading their ideology incels draw on coded and specialised vocabulary, characterised by gender-based lexis, hate speech, misogyny, and a dehumanised view of male-female relationships (e.g. Bogetić et al., Reference Bogetić, Heritage, Koller and McGlashan2021; Koller, Krendel & McGlashan, Reference Koller, Krendel and McGlashan2021; Pelzer et al., Reference Pelzer, Kaati, Cohen and Fernquist2021).

A distinct aspect of incel language that has received far less attention, however, is to do with race. The incel community is racially diverse, and active in discussions of race and constructions of specific in-group racism (Jaki et al., Reference Jaki, De Smedt, Gwóźdź, Panchal, Rossa and De Pauw2019). Overlaps between incel and racist agendas have been increasingly noted in research and commentary (e.g. Baele, Brace & Coan, Reference Baele, Brace and Coan2021; Hoffman, Ware & Shapiro, Reference Hoffman, Ware and Shapiro2020). Though typically not linguistic in approach, this research highlights aspects of incel language that echo the wider ideological traditions equating ideal masculinity with whiteness, and framing it as threatened by immigration, cultural dilution and left-wing activism, to the point that some theorists describe incel communities as an outpost of a newly emergent, abject and fascist form of masculinity (Kelly & Aunspach, Reference Kelly and Aunspach2020). For gender scholarship, this racial and racist dimension is a reminder that gender is always produced at the intersections (Hall, Levon & Milani, Reference Hall, Levon and Milani2019) of multiple categories and multiple systems of power. It is also a reminder of the long theorized (e.g. Bucholtz, Reference Bucholtz1999) but often neglected aspect of race in formations of hegemonic masculinity. For linguistic scholarship interested more narrowly in incel subculture's jargon, this again highlights its many social dimensions beyond just gender.

This paper aims to sketch the racial and ethnic dimension of incel vocabulary. I will show that incels’ racialFootnote 2 terminology is grounded in figurative language, and based in four specific conceptual domains, which leave a productive basis for introducing further neologisms mixing gender and race connotations. The race terms help understand systems of belief in the community, specifically the dehumanised, the hierarchical, and the eugenic-genetic imagination of human nature. More broadly, they reveal some wider processes of intersectional, figurative lexis, whose patterns merit more attention in research on the Manosphere.

The figurative vocabulary of incels: Gender, race and conceptualisation of human beings

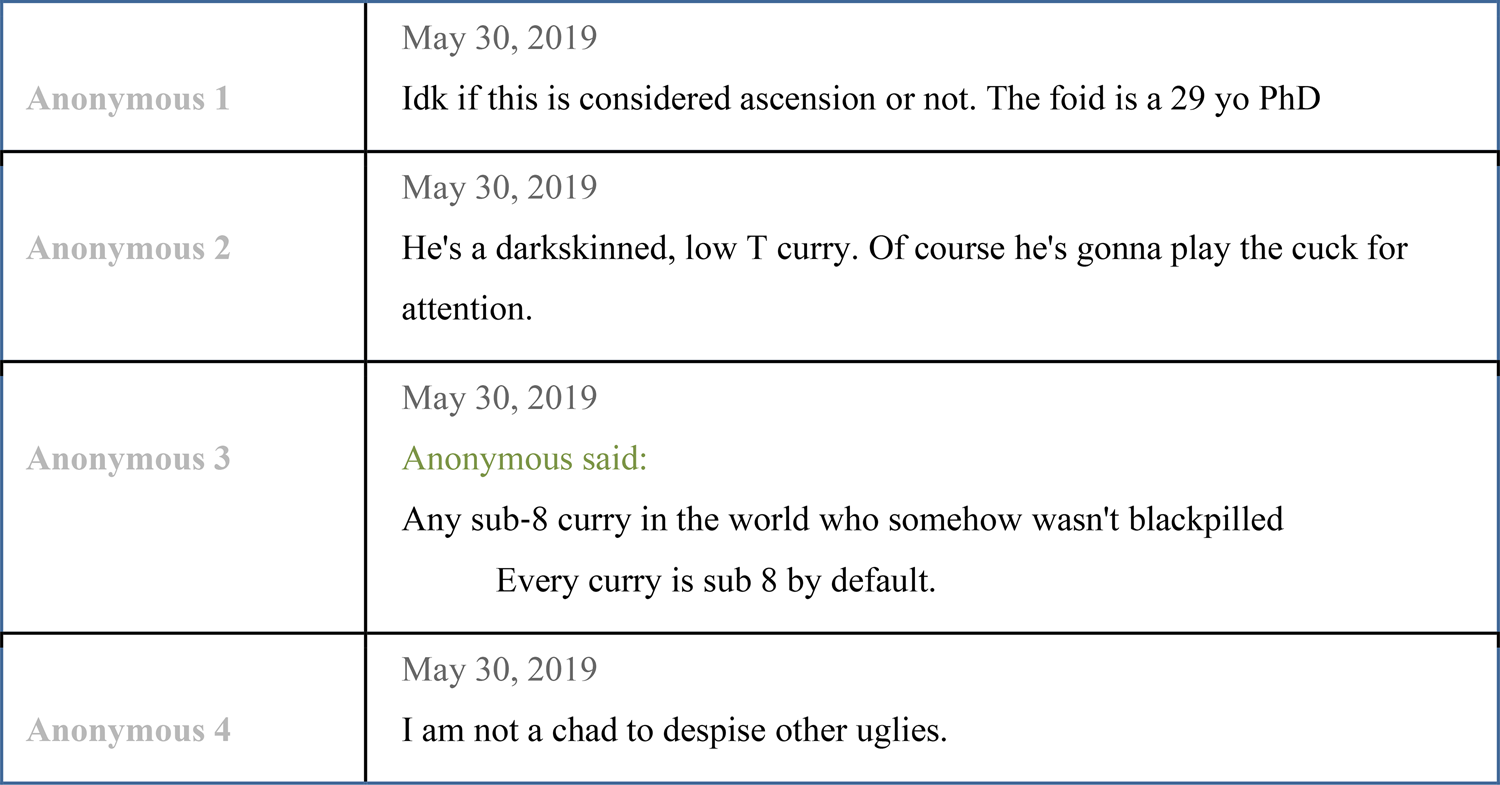

A first-time visitor to incel online forums would likely find a large portion of their language incomprehensible. Indeed, shared vocabulary is the main symbolic connection for the incel subculture – a true ‘cryptolect’ (Gothard et al., Reference Gothard, Dewhurst, Minot, Adams, Danforth and Dodds2021) characterised by idiosyncratic orthography, word play, arcane humour, and a fast-shifting terminology composed of neologisms ‘that split and grow like hydrae’ (Burnett, Reference Burnett2021: 1), with an often impenetrable ironic coding. Within this jargon, still, reference to people appears to be one major point of lexical innovation. Linguistic research on incels suggests that this community uses specific language to lexicalise ideologies towards men and women (Heritage & Koller, Reference Heritage and Koller2020), which according to some authors resembles that of pornography (Tranchese & Sugiura, Reference Tranchese and Sugiura2021) and has been turning increasingly aggressive over time (Papadamou et al., Reference Papadamou, Zannettou, Blackburn, De Cristofaro, Stringhini and Sirivianos2021) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. A thread on a celebrity accused of rape (from incels.is)

The hard-to-penetrate neologisms like those illustrated above are noted immediately upon visiting the incel fora. While some of these forms are incel-specific, interdiscursive connections exist with other forms of subcultural argots (as is the case with cuck [cuckold], cf. Bhat & Klein, Reference Bhat, Klein, Bouvier and Rosenbaum2020) long developing in subcultural online spaces such as Reddit and 4Chan (Marwick & Caplan, Reference Marwick and Caplan2018), as well as with other (see Koller et al., Reference Koller, Krendel and McGlashan2021; Krendel, Reference Krendel2020) Manosphere communities (as is the case with the Manosphere's notion of the black pill). In this respect, incels and their jargon need to be seen as an outpost of a broader masculinised and misogynistic internet, and are also important for their potentially mainstreaming (Koller et al., Reference Koller, Krendel and McGlashan2021) flows into other social communities and discourses.

In terms of linguistic realization, a scrutiny of the concrete lexical instances illustrated above draws attention to one pattern. A major aspect behind the productivity of incel vocabulary appears to be its conceptual grounding. Incels use ample figurative language, specifically metaphor and metonymy (cf. Bogetić et al., Reference Bogetić, Heritage, Koller and McGlashan2021; Lilly, Reference Lilly2016), in constructing their innovative lexis. Most of the less penetrable jargon above can be traced to metaphorical and metonymic origins, producing terms that stabilise within the discourse.

Cognitive linguists have long shown that metaphor and metonymy are not only embellishments of speech, but also reflect and affect our thought about particular concepts, by helping us think and talk about abstract concepts by drawing on more simple, concrete concepts (Lakoff & Johnson, Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980). For example, in the Western culture, life is often conceptualised as a journey, discussed as going somewhere, trying to get somewhere, going in circles or spinning our wheels (ibid.), which has implications for how we think about our lives and the ways they should be unfolding. In more structural terms, this particular metaphor connects the abstract target domain, that of life, to a more concrete source domain, that of a physical journey.Footnote 3 Similarly, such figurative connections between domains can have specific implications in specific discursive contexts, such as, for instance, in racist public discourses representing immigrants using the domains of animals, plants or natural disasters (swarming, crawling, flooding over borders, cf. Musolff, Reference Musolff2015), often in lexically innovative ways.

For the purposes of this analysis, put most simply, metaphor is defined as the process which allows us to reason about abstract concepts by drawing on more concrete concepts, like describing life as a journey (‘going somewhere in life’), or importance as size (‘a big day’). It is based on similarity, or comparison, between the concepts (e.g. life being like a journey). Relatedly, on the other hand, metonymy allows us to reason about one concept by drawing on another concept which is related to it, like referring to a person via body parts (‘I need a pair of strong hands’). It is based on contiguity, or relatedness of the senses (e.g. the strong hands being part of the person). The expressions can be conventional, but also new and creative, as in the famous example of ‘Ham sandwich wants his check’, where waiters use the food order for person metonymy (Nunberg, Reference Nunberg1978). It is easy to see how the processes may be productive in incel lexis, especially in their pejorative and dehumanising references to women and men (e.g. women as whales, dry-cunts; men as meerkats, tinydicks).

Further, the fact that the figurative language of incels carries a racial dimension is not surprising if we acknowledge their deep imbrication in the alt-right discourses. As a community which positions itself against political correctness, feminism and ‘social justice warriors,’ the incel subculture has constructed its own figurative conceptualisation of ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ races, which interact with ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ masculinity and femininity (Ging, Reference Ging, Ging and Siapera2019). As Kelly and Aunspach (Reference Kelly and Aunspach2020) note, such representations suggest that incel discourses are not only to do with gender and sexual repression, but also to do with a racist, white militant extension of compulsory sexuality; in their view, such intersections of gender, sexuality and race give a novel understanding of the role that the very idea of the ‘male sex drive’ can play in myths motivating fascism and the politics of the alt-right – a theoretical-political dimension that yet awaits scrutiny. Still, this interplay of figurative language, racism and misogyny has received less attention in linguistic research, despite indications that it is of relevance in their spread of hate speech lexis, and in their development towards more extreme discursive representations (Lilly, Reference Lilly2016).

The following examination will sketch incels’ metonymic and metaphorical racial terminology, with the aim of giving an insight into racial aspects of incel vocabulary, and decoding their basic meanings and discourse patterns.

Data and method

As an online subculture, incels congregate on fast-growing online forums of their own. While there is an increasing tendency for forums of this kind to get banned due to offensive content and incitement to violence (e.g. the r/incels subreddit, banned on Reddit in November, 2017), the effects of such de-platforming are as yet hard to assess, as users seem to migrate relatively quickly to new sites. For purposes of this work, a specialised corpus was compiled from the largest incel forum incels.is. At the time of writing, incels.is (previously incels.co, and before that incels.me) is a major channel of incel communication, with over six million posts, 300,035 threads, and 13,954 active members.

The corpus comprises 30 randomly selected threads comprising 29,244 words, including both original posts and thread comments, posted between 2019 and 2021. Given the focus on the words relating to people's race and/or ethnicity, a wordlist of race-ethnicity terms was compiled. Specifically, all the tokens that designate people in the corpus were identified semi-manuallyFootnote 4, and from the wordlist thus compiled, all the tokens that designate people's race/ethnicity were identified. In the present analysis, the decision was made to retain only noun forms as specifically naming people of certain race/ethnicity.

Two research questions are behind the analysis of the corpus.

RQ1. Which racial metaphors/metonymies are observed in incel neologisms referring to people?

RQ2. What patterns are of note across such racial identity representations, and in the wider discursive use of the neologisms?

Following the interest in metaphor and metonymy, the process of metaphor and metonymy identification followed the well established MIPVU procedure (Steen, Reference Steen2010), as well as a related version that accounts for metonymy (Biernacka, Reference Biernacka2013).Footnote 5 In this manner, the race/ethnicity wordlist was annotated for conceptual processes (e.g. metaphor, metonymy), and also lexical reference (gender, race, ethnicity, e.g. ‘white man’, ‘black woman’, ‘non-white person’, ‘Indian person’), and morphological process (e.g. affixation, compounding, conversion). In a quantitative overview, the corpus was analysed using the freely available LancsboxFootnote 6 software (Brezina, Timperley & McEnery, Reference Brezina, Timperley and McEnery2018). The main corpus method used was the identification of keywords, ie. words that statisticallyFootnote 7 stand out in a discourse, long known in corpus linguistics to reveal the ‘aboutness’ of a text.Footnote 8 This provided an insight into the standout race/ethnicity lexemes, as well as the general salience of such terms in the corpus; the following description in the analysis, however, included the whole wordlist of race/ethnicity terms mentioned above. The analysis also involved scrutiny of the concordance lines (ie. lines that list uses of the node word in its sentence context) via Lancsbox, and a broader discursive analysis, that helped to situate the vocabulary in context and understand its role in incel ideology. In part, the quantitative analysis complements the growing number of corpus-based studies of the incel vernacular (e.g. Koller et al., Reference Koller, Krendel and McGlashan2021; Krendel, Reference Krendel2020; McGlashan & Krendel, Reference McGlashan and Krendel2020), but retains the focus on race terms. Still, while the analysis departs from the quantitative, corpus-attested findings, it then turns to a primarily qualitative examination of the contextual meanings and discourse patterns surrounding the terms of interest. This discursive element of the study is grounded in discourse analysis and discursive approaches to metaphor and metonymy (Charteris–Black, Reference Charteris–Black2004), seeing figurative language as a way of conceptualising social actors with implications for the (re)production of social ideologies (van Leeuwen, Reference Van Leeuwen2008).

A quantitative look: Race terms and reference to people

In responding to RQ1, establishing the racial metaphors/metonymies used in the incel neologisms, keyword analysis was a useful quantitative step showing the place of several race terms in the top keywords’ list. Using the whole wordlist in a subsequent qualitative metaphor/metonymy analysis gave further insights into the figurative language groupings and their meanings in context.

Keywords and standout race terms

Among the top nominal keywords referring to people, a notable subset includes race terms, taking up six positions in the top-20 list (bold in Table 1 below). Moreover, among the the very top ten keywords, alongside incel, and foid, femoid (offensive machine-based reference to woman as ‘humanoid’), and bitch, are racialised terms Chad and currycel.

Table 1: Top nominal person-reference keywords in the incel corpus

Orientation towards gender is clear from the top keyword list, with gender labels like man, guy, woman being a major subset. The second major pattern, however, is reference to racialised gender identities (marked bold) that are the focus of the current study.

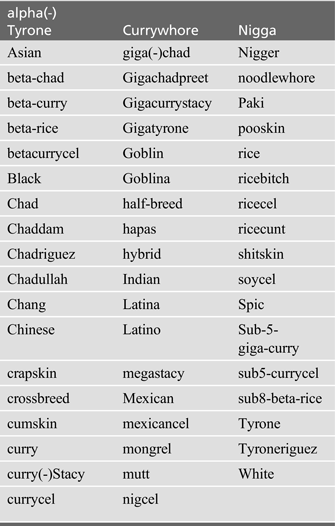

Further, in total, there are 551 tokens of race/ethnicity terms, with 56 different word types (the full list is in the Appendix). A smaller segment of these (N = 12) are well-established ethnonyms (e.g. Asians) and ethnic slurs in English (e.g. n-----), while the majority (N = 44) are innovative incel lexis, much of which would not be comprehensible to a non-member (e.g. Chadulla, curry, Tyrone).

To understand how terms like curry or Tyrone come to refer to people of particular race and ethnicity, we must understand them as having figurative meanings, which get conventionalised within the incels’ online community. In the analysis below, I will show that the terms in the list in fact belong to four major groups of figurative language, grounded in metonymy and metaphor, namely: personal name for person / (member of) group, food for person / (member of) group, skin (colour) for person / (member of) group, genetic makeup for person / (member of) group.

Incel neologisms as racial metonymies and metaphors

The incel neologisms identified in the corpus include words with primarily figurative meanings. They span most notably metonymy, but also metaphor, or both. While the figurative expressions themselves are diverse, they fit almost neatly into four categories of conceptualisation, based in four conceptual domains that are responsible for producing new incel lexis. The domain mappings are presented below in the cognitive-linguistic form of ‘X for X’, while the analysis will focus on lexical realisation and use.

PERSONAL NAME for PERSON / (MEMBER OF) GROUP

Incels have developed a range of references to racialised gender archetypes via personal names that take on a general meaning. The conceptual process behind such terms involves metonymy, which can be labeled personal name for person / (member of) group.

Metonymic person naming is in fact a feature of incel vocabulary more broadly, in ways that not only classify men and women, but also rank them on a scale of attractiveness or sexual prowess. For example, Stacy stands for women deemed good-looking, Becky for those deemed average-looking (the two lexemes have been spreading fast in general online English). Still, a significant point of reference for the naming vocabulary specifically involves race and ethnicity, and racialised male figures in particular.

In the corpus, the top such term by frequency is Chad (N = 194), one of the central person references of incel discourse: a white alpha male, whose superiority in terms of attractiveness stands in opposition to the inferior incel. While we might expect the racial characteristics of the Chad to be less visible, given how well-established the term's meaning is, the whiteness of Chad is in fact often directly referenced, especially in contrast with non-white masculinities:

(1) Asians getting cucked by white chad even in Manga

(2) Obviously she didn't make it clear if she wanted a Chad, or a black ass Tyrone scum.

Metonymic cover terms for non-white identities occur with varying use. The major non-white metonymic label is Tyrone, referring to a black version of Chad, but with more prominent racial characteristics. Tyrone appears to carry shifting connotations depending on the context of the discussion, including pure attractiveness and ‘alpha-masculinity’, sexual prowess, as well as aggression and violence described as desired by women (foids would rather risk be murdered by an alpha Tyrone than to date an incel).

Other non-white male figures include the Tyroneriguez (Black and Mexican), Chadriguez (Mexican Chad), Chadpreet (Indian Chad), Chang, (East Asian Chad), Chaddam (Arab Chad) and Chadullah (Arab Chad). As with the other name categories, capitalisation appears optional, so e.g. chang and tyrone also occur as common nouns. The origin of the name selection is not always easy to see, though cultural associations or names deemed typical in particular regions can be stipulated.

FOOD for PERSON / (MEMBER OF) GROUP

The second category of metonymy-based neologisms from the incel subculture comes from the food domain. In this category, conceptualisation is grounded in the metonymy food for person / (member of) group. Specifically, the food stereotypically linked to certain races and ethnicities is used for the person of that race or ethnicity; the term is lexically realised by affixation, adding the -cel affix from the lexeme incel.

While the -cel affixes are very productive in incel vocabulary (e.g. gymcel, fatcel), the food domain appears to be reserved for the racial/ethnic terminology. It produces varied references to incels of particular race and ethnicity, such as ricecels for the Chinese or Asian, or currycels for the Indian:

(3) Bitter pill to swallow for ricecels: we are inferior to white men in every possible way. Even the one supposed saving grace for Asian men that we have higher IQ is a straight up delusion.

(4) So are you suggesting me to stay in india among currycels where I earn mediocre salary?

The same metonymic conceptualisation can be realised through affix deletion, where the -cel affix is eliminated. Here the food term itself stands for the person, such as a curry, curries, a rice.Footnote 9 These terms seem to still typically refer to currycels, ricecels, ie. to incel men, but some instances of more general meaning are noted as well. The productivity of coinages of this kind can be explained by what Denroche (Reference Denroche2018) described as ‘metonymy extension’: the production of novel expressions which derive from the same conceptual metonymy, and get established and spread across a text. Our online data demonstrate how the process can operate across an entire in-group discourse, open for development at any point, across texts, posts and time.

Through metonymy extension, finally, a few instances of the food compounds refer to women: noodlewhores, currywhores, ricebitch, ricecunt, and curry(-)Stacy.

(5) You don't have to look at currywhores ‘fucking and kissing’ chadpreets.

(6) Us curries are a weak conquered race. Whose only purpose is to move to the west, work and study while white chad fucks curry stacy (white guys hate currywhores).

The terms with female reference are typically clearly offensive in their very word form, mixing gendered and racial connotations to produce specific misogynist senses. This misogyny targets female sexuality, but often covers racialised gender associations and ‘unnatural’ oppositions (e.g. chad vs. curry stacy). On the other hand, the food-based references that refer to incels carry different shades of negative evaluation, where the common racial hate speech combines with negative representation of incels as a more general group. In this sense, the establishment of this kind of offensive vocabulary needs to be understood in the context of pejorative representations of incels themselves, with non-whiteness simply adding to lower value in the incel worldview.

SKIN (COLOUR) for PERSON / (MEMBER OF) GROUP

The third category encompasses offensive word forms where the metonymy of skin (colour) for person / (member of) group – a realisation of the common wider metonymy of body part for person / (member of) group – is in operation:

(7) And curries cope by saying ‘b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-b-ut stupid cumskin curries in the west are the smartest and highest earners!’ - yeah, because the top .0000001% of your shithole 1.5 billion subhuman pooskins came here and STEMcuck.

(8) No, I will sit back and watch another shitskin Tyrone try to win a cumskin cunt

Overall, these coinages are not as productive in their realisation as the ones from the food domain, with only four forms found in the corpus: cumskin, and the synonymous shitskin, pooskin, crapskin. Nevertheless, they are prominent and well-established across the discourse, used similarly for men and women.

Ethnophobic terms in English have been shown to typically contain components of colour in their semantic structure, in ways that rely on metaphor, metonymy, or both (Honta, Pastushenko & Borysenko, Reference Honta, Pastushenko and Borysenko2019). The above neologisms build on such established conceptual processes, again via metaphor extension, but produce novel, in-group ethnophobic terms not noted elsewhere in research. The scope of reference for these terms is reserved for the contrast between black (shitskin, pooskin, crapskin) and white (cumskin), in line with research showing that ethnicity and colour conceptualisation in the anglophone world tends to manifest the opposition of ‘white’ vs. ‘non-white’, rather than the universal opposition of black and white (Honta et al., Reference Honta, Pastushenko and Borysenko2019; cf. Wierzbicka, Reference Wierzbicka1996).

Like all of the other described race/ethnicity neologisms, the forms are strongly value-laden, and typically occur in clearly racist and often aggressive remarks. Cumskin carries the offensive overtone, but concordance analysis shows that its connotations in context are primarily positive (e.g. cumskin fuckers outdo Tyrone in literally everything); the term reflects possibilities of mixing offensive reference with positive evaluation, set within a wider system of classification.

GENETIC MAKEUP for PERSON / (MEMBER OF) GROUP

The fourth group of neologisms is grounded in somewhat more complex conceptual processes, based in both metaphor and metonymy. Some illustrations will be useful at the start:

(9) No wonder hybrids have taken root [ . . . ] and the genes of half-breed hapas can only keep spreading faster.

(10) Im not a rich cumskin with european heritage, I am an abhorrent crossbreed mutt

In this group, the racial/ethic reference comes from the domain of plants and animals, often with unclear demarcation between these two (taking the definition of hybrid, as ‘the offspring of two plants or animals of different species or varieties’, Oxford English Dictionary; meanings are often clearer from sentence context, e.g. from taking root like plants in 9). The connection between two different domains, people and plants/animals, is based on similarity, and is hence metaphoric. At the same time, all the terms from this group carry a connotation of mixing, most basically put, the mixing of genes. This connection is between two related domains, that of a creature and its perceived (mixed) genetic makeup, and is hence also metonymic. The terms produced in this way either directly refer to hybrids and half-breeds, or specifically in animal (dog) terms of crossbreeds, mongrels, and mutts, or with the more general ‘half-breed’ label of hapas. The domain of genetic makeup is hierarchically superimposed to plants and animals, though both levels of conceptualisation are relevant in the discourse.

The human genetic makeup is in fact a major conceptual thread connecting incel racial terms and underlying incel ideology more broadly. It echoes old eugenic ideologies, along with the contemporary nationalist constructions of superior white masculinity as threatened by immigration and ‘cultural dilution’, and in turn, connects them to gender ideologies within this specific subcultural discourse.

The ‘gene mixing’ itself referred to via the racial terms is conceptualised metaphorically, whereby good genes can get diluted or contaminated, so the whole white race is at risk of getting corrupted, or infected from within:

(11) Yes and if a white woman wanted you as a currycel, your genes would dilute hers and your offspring would be ugly halfbreeds

(12) Even if i was chad i wouldnt be able to get myself with a white girl. i just feel bad about corrupting the white race with my hapa genes.

Finally, we can note that there is only one pair of terms not fitting the above four-fold grouping, namely reference to people as goblin/goblina. The terms, based on the image of physical characteristics and body size are also obviously figurative in nature, and though not grounded in the same conceptual domain mappings as the above, carry the same pejoration sense in reference to self and other.Footnote 10

The examples from the above four groupings show that incels use the offensive references to ‘race mixing’ (a common phrase in the incel vocabulary) not only for others, but also for themselves, to position their own masculinity as doubly inappropriate if they are both incels and non-white. This leads us to the second part of the analysis that looks at the wider discursive patterns in this data.

Racial representations and the wider discursive patterns

In responding to RQ2, concerning the notable patterns occurring across such racial identity representations, and the wider discursive use of the neologisms, two findings emerged from the qualitative analysis. One concerns a specific lexical strategy in the neologisms in question, used to represent social actors on a hiearchy and scale. The second concerns a wider discursive tendency for the lexemes in question to occur in coordination, in particular to create hierarchisation or ‘genetic’ differentiation.

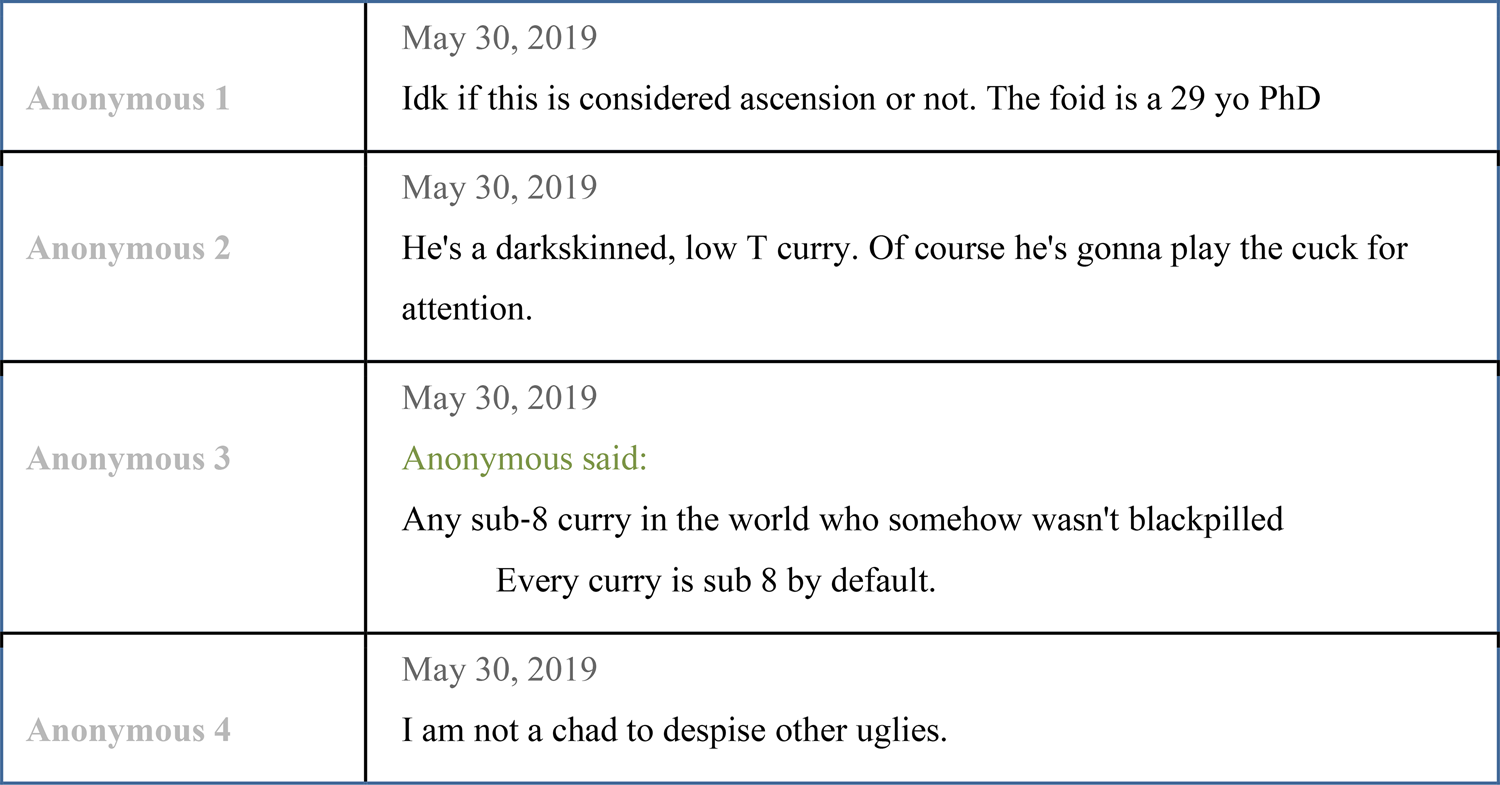

Racial identity on a hierarchy and scale

In incels’ conceptualisation of people, men are often positioned on a hierarchy for their masculinity, while women and girls are seen as inherently inferior to men and thus only ranked in terms of their attractiveness to the posters (Heritage & Koller, Reference Heritage and Koller2020). However, hierarchies in incel discourse are not only based on ‘appropriate’ and ‘inappropriate’ masculinities and femininities, but also on other intersecting categories such as race. A notable feature of the terms from my race/ethnicity wordlist is their use with ranking attributes: giga, mega, uber, alpha, beta and sub. Lexical and corpus classification is somewhat complicated by varying form and orthography, including actual single words (gigachad), hyphenated forms (giga-chad), but also two-word, adjective + noun forms (giga chad).

(13) What's more annoying, beta-chad or manly chad?

(14) My dad is an alpha Tyrone.

(15) I met two beta-curry bitches.

(16) Even if u get gigacurrystacy like the ones in bollywood movies, shed probably divorce/#metoo (section 498A) you

The evaluative senses in all examples of this kind are established via interaction with the gendered meaning (e.g. a beta-chad or beta-curry rank different types of racialised masculinity). They extend the hierarchisation and the alpha/beta dichotomy otherwise more widely present in the western culture, and elsewhere in the Manosphere (cf. Koller et al., Reference Koller, Krendel and McGlashan2021), while also showing the multifaceted intersections of evaluative and normalising discourses in gender-based communities (cf. Bogetić, Reference Bogetić2013, Reference Bogetić2021).

As illustrated above, giga, mega, uber, alpha, beta are used for both men and women. The sub + number description, however, is reserved only for men:

(17) I am a sub5-currycel who is living in india

(18) The guy's a sub-6 shitskin

(19) Any sub-8 curry in the world who somehow wasn't blackpilled before that whole shit has absolutely no excuse now. Millionaire, popular comedian and TV star, he has a completely consensual encounter with her and still gets called a rapist because he's a beta curry manlet.

Again, there are sub- prefixed coinages as individual words (listed in the Appendix), but also two-word phrases. Descriptions of this kind construct a kind of masculinity ‘below a threshold’, where the low position on the scale means a subhumanized nature. Again, the hierarchisation must be understood as intertwined with the wider victimisation discourse, in which the pejorative references construct incels’ own ‘non-whiteness’ as a major obstacle to their fullfillment in their romantic lives. It is also of note that such representations are repeatedly found in references to rape (16, 19), where the sub-men who somehow have sexual relationships with higher-ranking women are victims of #metoo and ’feminist accusations’, and need to be blackpilled to the ‘anti-men’ reality.

Discourse patterns: Coordinated hierarchisation and scientifisation of racism

As many of the above examples have suggested, incel racial terms have a tendency to appear in proximity to one another, often in contrast, or in coordination of two or more terms. Over one half of the total items identified (52%) are collocated with at least one other race/ethnicity item within five spaces to the left or right.Footnote 11

This pattern relates two aspects of the racial lexis that we have seen above. One is the association with hierarchy and ranking, which is often effected by direct comparison in the form of ‘X unlike Y’, ‘X not Y and Z’ etc. References of this kind commonly involve coordinated strings mixing multiple race and ethnic terms and slurs:

(20) Inventions come from whites, not curries or rice.

(21) The Chad knows his bitches, unlike any tyrone, curry, rice, or mongrel like myself.

The second aspect concerns comparison with specific reference to genes and biology. In their accounts of race, incels often draw on pseudo-scientific vocabulary, combining race/ethnicity references with biology terms, acronyms and statistical references. Expressions from the plant/animal category make this most visible, but other race terms are often embedded in similar sentence context. The combination of scientific terminology and piled-up ethnophobic neologisms, however, often creates an unusual stylistic mix:

(22) Lower races are known as such by science. And results of gene-mixing are not a secret [ . . . ] Only in the USA the numbers have grown by 12% from 2000s as rice, curries, other shitskins and mongrels swarmed, but they don't mind their DNA, just keep on throwing out their autosome 21 half-breed offspring

More broadly, examples of this kind echo the combination of the ‘new biologism’ (Cameron, Reference Cameron2010) and scientifisation characteristic of the ‘anti-gender animus’ in sociopolitical discourses of late (Borba, Hall & Hiramoto, Reference Borba, Hall and Hiramoto2020), which form a background for the need to react to ‘unnatural’ situations. Incels amplify these discourses through pseudo-scientific evidence, combining arguments of a biological basis of gender difference, and a biological basis of race difference. It is of note that the posts are often aggressive, using collocated race terms to announce hatred to the point of supporting a race war (N = 7 in the corpus) that is near:

(23) The race war is coming, and you're either in or out, chads, tyrones or changs.

Conclusions

Incels produce a rich set of neologisms, predominantly pejorative, to refer to people. While scholarship has focused on the gender dimension of such terms, race is another prominent aspect in the vocabulary. Among the top keywords denoting people found to stand out in the present corpus, several refer to racialised (and always simultaneously gendered) figures, and dozens more have been identified. This lexis is primarily based in figurative, metonymic and metaphorical language, namely, across four specific conceptual domains: personal name, food, skin (colour) and genetic material. The prominence of figurative language is in line with earlier findings on racial hate speech (e.g. Musolff, Reference Musolff2015). Still, the incel terms reflect the productivity of metonymy and metaphor for coining novel, in-group racist vocabulary, via the processes of stereotypicalisation, metonymy extension, and normalisation across discourse.

Beyond lexis, incel race terms are a window to the community's wider systems of belief. On the one hand, they reflect an ideology that is primarily marked by misogyny, with all the female-related terms having offensive meaning, typically used in relation to male-related terms. On the other hand, the fact that a number of the racialised lexemes in fact refer to men, however, and often to incels themselves, shows not only the traces of a specific internalised racisim, but also the complexity of hate speech in this community more broadly. It must be understood as essentially constructing a bleak view of humanity (part of the ‘black pill’ ideology, cf. Pelzer et al., Reference Pelzer, Kaati, Cohen and Fernquist2021), which is nevertheless multi-directional, including references to self and other, man and woman, incel and non-incel, white and non-white, rather than directed at a single group of social actors. At the same time, as we know that the targets of the physical violence perpertrated by incels are primarily women, this also shows that linguistic nuances do not directly translate into the real-world distribution of antagonisms.

The race terms altogether semantically connected via three characteristics of incel conceptualisation of people, and incel ideology more broadly: dehumanisation, hierarchisation and eugenic-genetic imagination. Many of the metaphors and metonymies show a dehumanised representation of particular races (as food, animals, plants). For incels, the dehumanised reference is at the same time deeply hierarchical, with the giga-, alpha-, beta- neologisms putting the race labels on a scale, in a ranking that is jointly based on race and gender. Notably, the hierarchies of masculinities and femininities are grounded in a biological, genetic imagination of race, reducing people to genetic material that can be essentially of high or low quality, diluted, mixed or pure. Rather than an incel product, this imagination echoes the wider trend of ‘scientific’ normalising of problematic ideologies that we see today much more broadly, from sexism to neofascism, in this particular community culminating with the idea of a race war that is coming.

Finally, the racialised masculinities and femininities captured by incel neologisms remind us of the importance of looking not just at single categories such as gender, but also at how gender may intersect with other categories to create constructs relevant to a subculture. As incels attract increasing attention due to their apparent potential for extremist violence, understanding their language is indeed a path to understanding the overlapping motives that drive extremist recruitment. As the present analysis has suggested, this is an important challenge given the evident elusiveness of incels’ figurative rhetoric, but also given the interdiscurive flows that may bring the jargon and its ideologies into more mainstream usage. Intersections of gender and race appear to be a major knot in this respect that is as yet undercomprehended. Ultimately, by decoding the processes behind incels’ intersectional, figurative lexis, together with the intersectional patterns of ideology, sociolinguists can significantly contribute not only to capturing this emerging English cryptolect, but to reaching deeper and less sensationalist understanding of the Manosphere's online communities.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges funding by the project ‘(Re-)imagining language, nation and collective identity in the 21st century: Language ideologies as new connections in post-Yugoslav digital mediascapes (project number N6-0123)’ by the Slovenian National Research Agency (ARRS).

Appendix: Lexemes of race/ethnicity reference in the incel corpus

KSENIJA BOGETIĆ holds an MA in English (Oxford University) and a PhD in English linguistics (University of Belgrade). She has taught at the University of Belgrade, Serbia, and is a Research Associate at the Academy of Sciences and Arts, Slovenia. Her research interests span various intersections of language and the social world, including language ideology, language, gender and sexuality, media discourse, language and metaphor, in both anglophone and Slavic contexts. Starting in 2022, she will be leading a project on discourses of COVID-19 funded by the Marie Sklodowska–Curie (HORIZON 2020) scheme. She is currently editing a Special Issue of the Gender and Language journal on the topic of Language, Gender and Sexuality in Central and Eastern Europe (coming out Sept. 2022). Email: [email protected]

KSENIJA BOGETIĆ holds an MA in English (Oxford University) and a PhD in English linguistics (University of Belgrade). She has taught at the University of Belgrade, Serbia, and is a Research Associate at the Academy of Sciences and Arts, Slovenia. Her research interests span various intersections of language and the social world, including language ideology, language, gender and sexuality, media discourse, language and metaphor, in both anglophone and Slavic contexts. Starting in 2022, she will be leading a project on discourses of COVID-19 funded by the Marie Sklodowska–Curie (HORIZON 2020) scheme. She is currently editing a Special Issue of the Gender and Language journal on the topic of Language, Gender and Sexuality in Central and Eastern Europe (coming out Sept. 2022). Email: [email protected]