Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.

Benjamin Franklin

The aspirations and hopes for future mental health services are firmly set on applying the principles of recovery and finding effective and acceptable ways of enabling people who use mental health services to be in control of their own lives (Future Vision Coalition 2009). This involves not only structural and organisational changes to create new ways of working, but new forms of practice and a remodelling of skilled helping relationships to promote self-care and self-management. The ambitions of progressive policy (Reference Shepherd, Boardman and SladeShepherd 2008) and guidance (Care Services Improvement Partnership 2008) invite us to engage in a process of cultural change across mental health and social care services and stretching into society as a whole. There are clear implications for changes in workforce, training, outcomes evaluation and the nature of interactions between practitioners and people who use services (Reference Shepherd and BoardmanShepherd 2009). The big issue is clarifying future practice and how to achieve this.

There is already widespread interest and experience in ‘coaching’ in sport and business and the possibility has been raised that this knowledge and experience could be adapted for mental health practitioners as a wellness-focused approach to enable people to become more skilled in self-care and self-management, i.e. coaching for recovery.

The College emphasises that coaching and mentoring are beneficial for practitioners (Psychiatrists' Support Service 2008; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008) and there is extensive experience of coaching in other fields as a route to maximise potential. This article explores the initial steps of adapting these approaches to working with people who have significant mental health needs. The cross-over involved in seeking to apply an approach associated with success and thriving in high-functioning individuals to people with significant mental health problems also emphasises the common pursuit of well-being and happiness and ties in with the concluding observation in the position paper A Common Purpose that for the first time we are considering guiding principles and practices that are of equal value to the practitioner as to the service user (Care Services Improvement Partnership 2008: p. 26).

What do we mean by ‘coaching’?

Reference Skiffington and ZeusSkiffington & Zeus (2003) state that contemporary coaching approaches grew out of the theories and practices of Rogerian counselling based on humanistic psychology and have philosophical roots in constructivism and existentialism. ‘Coaching’ can be defined as a holistic orientation to working with people, to find balance, enjoyment and meaning in their lives as well as improving performance, skills and effectiveness. The term looks back to early forms of transportation, i.e. stagecoach or rail coach and literally means to transport someone from one place to another (Reference StarrStarr 2008). Conventionally, a coach (e.g. a sports coach) would have a specialised area of expertise and a successful track record in their particular area. Life coaches are not expected to have expertise in the specialist fields of their clients, but are expected to have completed formal accredited training to achieve core coaching competencies (International Coach Federation 2008) and maintain professional standards through continuous professional development.

What is the evidence in support of coaching?

Despite the popularity of coaching there has been little rigorous research into its effectiveness or outcomes. There is considerable testimony in support of improved company and individual performance, increased productivity, good staff retention and teamwork, although it is often linked to promotional materials of for-profit organisations (Coaching Clinic 2004). There is some evidence for the effectiveness of business and executive coaching, including return on investment (Reference McGovern, Lindemann and VergaraMcGovern 2001). A randomised controlled trial looking at the effectiveness of a preventive coaching intervention for employees at risk of sickness absence because of psychosocial health complaints concluded that coaching positively affects the general well-being of employees (Reference Duijts, Kant and Van den BrandtDuijts 2008). It follows that although coaching is an established and growing approach to enhancing performance in non-clinical populations, the lack of empirical support signals a considerable need for evaluation of effective methods, outcomes and limitations if coaching is to be adopted as a method of support for people with mental health needs (Reference Ramsay and KjeldsenRamsay 2005).

Life coaching in the context of recovery and long-standing mental illness

There is a broad overlap between the principles of recovery and those of life coaching (Table 1). The central tenet of recovery is an emphasis on ‘personal recovery’ alongside ‘clinical recovery’ (Reference Shepherd, Boardman and SladeShepherd 2008), which has been defined as ‘a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life, even with the limitations caused by the illness’ (Reference AnthonyAnthony 1993); recovery is a ‘unique process, a journey, with discovery of personal resourcefulness, new meaning and purpose in one's life’ (Reference Higgins and McBennettHiggins 2007).

TABLE 1 A comparison of core principles of life coaching and recovery-based practicea

| Recovery principles | Life coaching principles |

|---|---|

| Recovery is about building a meaningful and satisfying life, as defined by the people themselves, whether or not there are ongoing symptoms or problems | People are not broken; they do not need to be fixed. Coaching is about uncovering what people truly want, their core values and supporting them to be aware of their own resourcefulness |

| The helping relationship between clinicians and people moves away from being one of expert–patient towards mentoring, coaching or partnership on a journey of personal discovery | The coaching relationship is a partnership of equals, more than anything parental or advisory |

| Hope is central to recovery and can be enhanced by people discovering how they can have more active control over their lives and by seeing how others have found a way forward | People have the resources and skills to make any change they want |

| Recovery represents a movement away from focusing solely on pathology, illness and symptoms towards focusing on health, strengths and wellness | The power of focus – what we focus on we get |

| People are encouraged to develop their skills in self-care and self-management in whatever way works for them. There is no ‘one size fits all’ | People can generate their own solutions. An individual is ultimately responsible for the results they are generating |

| Recovery is about discovering and often re-discovering a sense of personal identity, separate from illness or disability | The past does not dictate the future. We need to listen to and acknowledge individual people's stories and past experiences but having done so support them to create new stories and unlock their true potential by taking action to change their lives |

| Finding meaning in and valuing personal experience is important, as is personal faith, for which some will draw on religious or secular spirituality | The spiritual aspect of coaching looks at who we truly are and our purpose in life |

Traditionally, people with mental health problems have been signposted to mental health services, which aim to diminish symptoms and disabilities, rather than towards life coaching, which seeks to develop resilience, strengths and performance. Increasingly, a new emphasis is being applied to mental health practice and services, derived from perspectives of people who have personal experience of mental health problems or use of services. This puts equal or more weight on what a person is recovering ‘towards’ and on the need and value of building a meaningful life and pattern of living apart from illness. This has been described as the difference between clinical recovery and personal recovery and whereas one is supported by evidence-based guidelines and treatment the other is supported by recovery coaching and support for self-management (Reference SladeSlade 2009a).

How does coaching differ from other approaches that promote well-being?

Skills of listening, questioning and building trusting relationships are common to therapy, counselling, mentoring and coaching, as is promoting awareness, responsibility and self-belief (Reference WhitmoreWhitmore 2002). Both mentoring and coaching may make use of counselling skills, but whereas in counselling proper they are usually focused on resolving particular problems, coaching and mentoring are focused on goal or role-related achievements, from ‘arriving’ to ‘surviving and thriving’, and thus include optimising success and fulfilling potential. Similarities and differences between coaching and mentoring continue to change. The College's Occasional Paper, Mentoring and Coaching (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008: p. 6), emphasises similarities between coaching and mentoring:

Most models of mentoring and coaching share the same basic premise, namely that the mentee is resourceful and that the key role of the mentor/coach is to help the mentee use this untapped resourcefulness.

However, there may also be differences in the relative importance given to experience or training. Preparation for coaching is dependent on being properly trained and having learned appropriate skills to an accepted level. It is therefore quite possible for an effective coach to work with someone without any specialist knowledge of their work or situation. In mentoring, the tradition has been of a more experienced colleague supporting someone with less experience and some mentorship schemes are explicitly set up on the basis that mentors will have a number of years' experience of a similar job (Reference Roberts, Moore and ColesRoberts 2002). Coaching tends to be for time-limited sessions, whereas mentoring is often conducted in the context of a longer-term supportive relationship. More recent models of mentoring (e.g. Reference Connor and PokoraConnor 2007) have placed less emphasis on the prior experience of mentors and more emphasis on training in mentoring skill, which then looks very much like coaching in a mentoring role. In practice, there may be no clear distinction and the terms are often bundled together and used interchangeably. The competing merits of qualifications over qualities would ideally be resolved by the coach or mentor having both.

Values, principles and practice

Tools

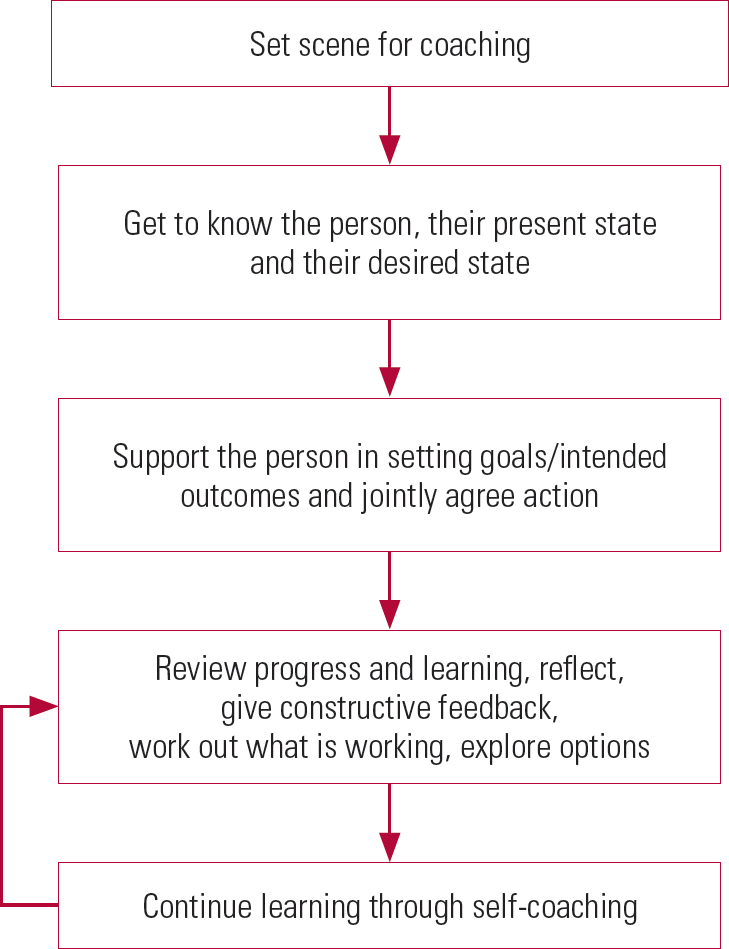

Typically, the coaching process (Fig. 1) involves the use of coaching tools (Box 1) and a conversational style of probing, listening, pausing and giving the person the space and time to reflect, being mindful of staying well-connected to the present rather than the past or future. Conflict between a person's desires and core values often results in under-performance and dissatisfaction in life (Reference MartinMartin 2001) and is invariably addressed through coaching. Active, intuitive listening includes skills of articulating, clarifying, using metaphor and meta-view, and acknowledging (Reference Whitworth, Kimsey-House and SandahlWhitworth 2005). This and skilful, outcome-focused questioning (Box 2), accompanied by genuine curiosity, are commonly used during the coaching process. Re-framing meanings attached to events or personal experiences (Reference O'ConnorO'Connor 2002) helps shift perspectives and challenges world views to support and stimulate a learning process. The GROW framework (Reference WhitmoreWhitmore 2002) is one of the most commonly used coaching tools to help people focus on the solutions rather than dwell on problems (Box 3). Whitmore states that the goal of a life coach is to ‘build awareness, responsibility and self-belief’, which compares to the main principles underlying recovery of ‘hope, agency (“control”) and opportunity’ (Reference Shepherd and BoardmanShepherd 2009: p. 1).

FIG 1 The coaching process. Adapted from Reference StarrStarr 2008 and Reference Skiffington and ZeusSkiffington & Zeus 2000.

BOX 1 Examples of commonly used coaching tools/concepts

-

• Basic understanding of the core coaching competencies

-

• Application of the Wheel of Life (Mind Tools 2010) and the GROW framework (Reference WhitmoreWhitmore 2002)

-

• Active, intuitive listening

-

• Skilful and outcome-focused questioning

-

• Identifying moving-towards and moving-away values and values that could be in conflict

-

• Aligning core values during goal-setting

-

• Awareness of basic human needs and the means used to meet them

-

• Re-framing meanings of experiences

-

• Exploring and/or jointly challenging safety behaviours or limiting beliefs

-

• Creating awareness

(Adapted from Reference Asher and HayAsher 2004; Reference StarrStarr 2008)

BOX 2 Some key questions in life coaching

-

• What do you do differently when you are content and enjoying yourself?

-

• What makes you laugh or smile?

-

• What do you like doing? What activities would you indulge in?

-

• What inner qualities do you think you have that make you likeable?

-

• What do you value in life? What does that do for you?

-

• What are you doing right now to honour your core values?

-

• What are you putting up with that you want to change?

-

• What would you do if you knew you wouldn't fail?

-

• If you had no fear, what would you ideally do in this situation?

-

• If you were the coach, how would you coach yourself to win?

-

• If you knew the answer, what would it be?

-

• What would the consequences of that be for you or for others?

-

• Who are you becoming?

-

• What are you settling for?

-

• How are you using your gifts?

-

• What are you holding on to that you no longer need?

-

• What one thing would you change for the better?

(Adapted from Reference WhitmoreWhitmore 2002; Reference Asher and HayAsher 2004; Reference MumfordMumford 2007)

BOX 3 Planning and goal-setting by making use of the GROW framework

| G = Goals | Setting clear goals (What do you want specifically?) |

| R = Reality | Exploring the current situation (What is happening? What action have you taken on this so far? What were the effects of that action?) |

| O = Options | Alternative strategies or courses of action (What are the options available for you to move forward? What else? Anything else? What are their pros and cons?) |

| W = Way forward | What is to be done, when, by whom and the will to do it (What will you do? Will this action meet your goal? What obstacles might you face? How can you deal with these? Rate on a 1–10 scale the degree of certainty you have that you will carry out the actions agreed. What prevents it from being a 10?) |

(Adapted from Reference WhitmoreWhitmore 2002)

Recovery-oriented practice

Recovery coaching – the adaptation of life coaching practice and principles in support of personal recovery – is an emerging practice in wellness-oriented mental health services. Recovery coaching starts from the premise that we have common needs and aspirations and is based on what the person desires as the outcome. This includes the person making and learning from bad choices/decisions and being honest and transparent about the limitations set by the duty of care. Reference Borg and KristiansenBorg & Kristiansen (2004) emphasised the importance of combining a high level of relationship skills such as empathy, caring, acceptance, mutual affirmation, encouragement of responsible risk-taking and a positive expectation for the future with other recovery skills as key ingredients of recovery-oriented practice. The concepts of choice and responsibility are central to coaching. Unless the person in coaching is willing to assume responsibility for his or her choices and actions, they may remain stuck in their problem state, not feeling able to act positively within their problem situation (Reference StarrStarr 2008).

Personal responsibility

This challenge to personal responsibility is both a difficult and pivotal shift in engaging with both coaching and recovery perspectives. The personal challenge involved has been robustly expressed by a leading activist and mental health consultant (Reference ColemanColeman 1999: p. 16):

We must become confident in our own abilities to change our lives; we must give up being reliant on others doing everything for us, we need to start doing things for ourselves. We must have the confidence to give up being ill so we can start being recovered.

From a provider perspective, Reference WatkinsWatkins (2001) believes that ‘People can take responsibility for themselves (though they might need encouragement to take it)’ (p. 67), which underlines one of the basic principles of recovery coaching in balancing hope, aspiration, expectation and realism. However, in taking these steps Reference StarrStarr (2008) usefully emphasised the importance of making a clear distinction between upholding confidence that people can progressively take up personal responsibility and attributing blame to them for the situations they find themselves in.

Reference BoyleBoyle (2003) has suggested that a core principle for coaching in mental health is the need for mental health workers to sustain confidence that people who use our services can set, own and achieve meaningful goals for themselves. But if the effectiveness of coaching is dependent on people's motivation and desire for things to change (Reference GashGash 2009), there are obvious complexities in applying coaching approaches to people with severe mental health problems.

Implications

Implications for people who use mental health services

Reference BoyleBoyle (2003: p. 3) described the benefits of coaching in the following way:

It [coaching] sees people in terms of their future potential, not their past performance so it offers users of mental health services the experience of achieving positive results through their own actions. Coaching in mental health complements other professional interventions by its focus on awareness, responsibility, performance and self-belief … Doubt, fear and unhelpful thinking are addressed as they arise, as obstacles to the person's goals and only in such a way that the person develops a strategy that they are confident will lead to the achievement of the goals set. As people achieve their goals their sense of personal effectiveness, self-esteem and autonomy grow and they choose to build on their success by setting further meaningful goals.

To benefit from coaching, people need to be willing to explore what is possible, to become their own experts not only in identifying early warning signs of their illness and what works for them but also in self-management and taking personal responsibility for improving the quality of their own lives while being supported by professionals. For a coaching approach to work, both the worker and the service user must make an active contribution. These shifts of power and authority are fully consistent with the hope of a ‘new relationship between users and services’ identified by the Future Vision Coalition (2009: p. 26). Whatever the present capacity of people using services to engage in a coaching relationship, workers can adopt a coaching stance and set the scene for the possibility of coaching relationships to follow.

Implications for carers and family members

It is a key observation that families and other supporters of people with mental illnesses play a crucial role in their journey to recovery and often have their own needs for recovery (Reference WatkinsWatkins 2007). Enabling family members to develop coaching attitudes and skills would not only enhance their capacity to be appropriately supportive but also address their own recovery needs.

Implications for workers

Developing recovery partnerships

Reference SladeSlade (2009b) and others (Reference Shepherd and BoardmanShepherd 2009) have asserted that a key cultural change and organisational challenge in recovery-oriented services is a shift towards helping relationships based as much as possible on partnerships. This is fully compatible with the model of role relationships in coaching, where the skills of the coach are a resource that is offered to work on the other's goals, providing choices and supporting people to develop and use self-management skills, rather than fixing the problem for them. This is also consistent with the shift of emphasis anticipated in recovery services from focusing on delivering treatment to taking a more educational stance of supporting self-care and self-management (Reference Shepherd and BoardmanShepherd 2009).

A flexible approach

Coaching can be used as either a formal coach–client approach or a set of skills and an approach to be used in any setting (Reference SmithSmith 2007). Some services emphasise that recovery coaching is a basic skill to be developed by all staff (Box 4). Having a degree of flexibility around the coaching style is important and with more severe problems may become more so. The aim is to be alongside the person and work on their goals and coach at their pace. To be able to recognise when to be challenging or supportive, firm or compassionate is important, as is the ability to tolerate ambiguity. It could be easier once the recovery relationship is well established and the person is ready for change.

BOX 4 Initiatives in the Devon Partnership NHS Trust

The Devon Partnership NHS Trust has declared a commitment to ‘Putting recovery at the heart of all we do’, which has led to production of a recovery guide (Devon Partnership NHS Trust 2008). This is now an accepted and widely endorsed framework describing the guiding values, principles, practices and standards of a recovery-oriented service. This includes an expectation that ‘The helping relationship between clinicians and patients moves away from being expert–patient towards mentoring, coaching or partnership on a journey of personal discovery’. This change of practice is described in the Trust's overarching policy guide Recovery Coordination (Reference MooresMoores 2008). It specifies that all practitioners will develop recovery coaching skills and adopt a recovery coaching stance at all levels of practice. This represents a major change process that is being led by the Executive Nurse and Trust Recovery Coordination team (led in turn by the Trust's recovery lead) through a series of master classes for clinical team leaders. This is an initial step in an ongoing process of clinical and cultural change, which will be supported by new supervision and personal development review policy, practice quality audits and key performance indicators across the Trust that monitor practitioner and team adoption of recovery-oriented practice and standards. The benefits of moving towards a coaching stance in routine practice have been described as applicable to the overall personal development of the individual people, their contribution to the team's performance and to the anticipated and intended change in work culture (Reference SladeSlade 2009a).

Understanding the individual

Those developing coaching approaches in mental health settings also emphasise the need to understand the obstacles people face in both engagement and progress:

The challenge for mental health workers is to work with a person's own perspective of recovery, and their own goal/wishes … we also need to be sensitive to the possibility that someone is selling themselves short, may experience internalised stigma (the notion that negative stereotypes and beliefs about mental illness have become part of the person themselves) or feel hostile towards services on the basis of previous experiences. As workers helping someone on their voyage of recovery, we need to find a way to work with the person to enable him/her to remove some of the barriers to success.

It follows that all mental health workers will need to be well versed in ‘keys to engagement’. Hence Reference WatkinsWatkins (2007) has emphasised the need for the worker to seek to understand the person's phenomenological world and engage through what the individual values. Recovery coaching emphasises the need to hold hope for the people using our services, to choose to believe that they are resourceful and to have a curiosity to find out their hopes and ambitions beyond their diagnosis, stories and sufferings, reconnecting with their capabilities, strengths and resources.

Supporting workers

It is paradigmatic that a move towards recovery-oriented practices should support the well-being of the workers too (Care Services Improvement Partnership 2008: p. 26) and it is reasonable that a shift towards recovery coaching practice could have a beneficial implication for the workers' well-being, team and organisational relationships.

Implications for service systems

Coaching is an established intervention to assist organisational change (Reference Treur and Van Der SleusTreur 2005). Reference SladeSlade (2009b: p. 26) states that ‘Evolving towards a recovery vision may prove impossible without fundamental transformation’, which amounts to putting values into practice. It is therefore suggested that an organisation wishing to adopt a recovery orientation could beneficially adopt coaching philosophy as a support for cultural change, which will require significant investment in training for attitude, skills and qualities (Box 5; Reference BoyleBoyle 2003). This includes incorporating recovery-supportive values into the relationships between the organisation and its workers, which is developed through practical tasks such as supervision, appraisals, training activities, capabilities and disciplinary procedures and which forms the leading approach to all change management. The organisation has to be clear and consistent, with its communication stating precisely why it is promoting recovery and recovery coaching so that all involved know what is asked of them and how and where to seek information and support. Finally, for a coaching culture to emerge, the contribution needs to come from leaders as role models and managers engineering operational changes and through valuing the contribution of every worker, and also through the extended network of stakeholders and other contributors.

BOX 5 Coaching experience of the Community Care Trust

The Community Care Trust is a third-sector organisation providing recovery services for people with mental health difficulties and a wide range of community network activities in south Devon, UK. It has 70 staff, 50 of whom are support, time and recovery (STR) workers. It works across three residential units and an open population of 400 people who become members of the service and use it on a flexible basis according to need. This service is recognised as a pioneering example of a recovery-oriented service network (Reference SladeSlade 2009a).

In 2006, the Trust decided to engage in a process of training and retraining for the entire staff in coaching as applied to recovery-oriented practice. Most of the staff have completed a locally devised recovery qualities experience training and recovery qualities coaching programme. Each participant also belongs to a coaching group which meets every other month to look at coaching in practice. These groups are led by lead coaches who have undergone advanced coaching training. The coaching groups are the main vehicle for developing practice and in this way the Community Care Trust aspires to embed the coaching principles and the recovery qualities throughout the organisation.

This fundamental reorientation of practice has brought its own challenges. Staff had to learn to understand and manage their anxieties about new ways of relating to people with new expectations of shared responsibility and co-working. As staff understood the importance of what they personally brought to the coaching relationship, it gave them confidence to experiment, learn and grow. The result was that relationships moved closer to becoming partnerships.

Further information is available from [email protected] and www.community-care-trust.co.uk

Making a start

The foundation has already been laid in terms of recognising the compatibility between the guiding values, principles and practices of recovery on the one hand and the recovery supportive potential of coaching practice and its practical applications in support of self-management, recovery-oriented care coordination, staff supervision and assessments on the other (Reference SladeSlade 2009a). Designing appropriate training programmes for implementation as part of continuing professional development for mental health workers would be the next step. Support for such training could emerge from National Health Service trusts (or boards in Scotland) setting up recovery education units as suggested by the Sainsbury Centre (Reference Shepherd and BoardmanShepherd 2009) and there are examples of some trusts, boards and services making a start (Boxes 4 and 5; Reference BoyleBoyle 2003). However, there is a particular need for trusts, boards and organisations setting up coaching initiatives to embed robust evaluation to support critical appraisal and ongoing learning.

Concerns and cautions

In a cautionary note, echoed by many others, Reference SladeSlade (2009b: p. 8) pointed out that ‘It is unhelpful to put expectations on a person who is still early in their recovery (what a professional might call acutely unwell) which they cannot even begin to meet’. There is an endemic concern in mental health services that proponents of new practices underemphasise the difficulties people with severe or long-term conditions may have in being self-determining – the so called ‘denial of disability’. This is one of the more frequently cited reservations in relation to adopting recovery-oriented approaches in psychiatry (Reference Davidson, O'Connell and TondoraDavidson 2006). A previous paper (Reference Roberts, Dorkins and WooldridgeRoberts 2008) explored the need for realistic expectations and constructive caution in the application of choice in support of recovery for people with impaired capacity who are subject to detention. However, that review and associated commentaries also upheld the proposition that there should be no ‘recovery-free zones in our services’, whatever the level of disorder or disability. Our traditional approaches have been generally criticised as overestimating risk and denying opportunity for discovery. Future-oriented perspectives such as that from the Future Vision Coalition (2009) and the consultation paper preparing for New Horizons (Department of Health 2009) express a clear intent to support a shift from the dominant emphasis on risk avoidance to promoting careful and creative positive risk-taking. Recovery coaching as described here would be a practice supportive of such a shift.

Challenges – personal, professional, institutional

Reference Whitworth, Kimsey-House and SandahlWhitworth et al (2005) described the coaching relationship as a ‘designed alliance’, with the power being granted to the relationship, not the coach. In mental health settings, we face a variety of challenging situations when the perception is that the person using our service has lost his capacity to participate in such alliances or partnerships, especially when acutely unwell or detained under the Mental Health Act. The power balance then may temporarily shift towards the practitioners making decisions on behalf of the person. However, the Code of Practice (Department of Health 2008) emphasises that the guiding principles for application of the Act include being respectful of people's needs and preferences and providing opportunity to participate as much as is practicable, with the aim of promoting recovery. Much of the guidance that follows continues to emphasise taking the least control possible of someone and for as little time as is necessary. A recovery coaching stance would therefore have application even in these most difficult of circumstances when people's readiness and willingness to take on personal responsibility may be heavily compromised by past experience or present difficulties. It would also support a desirable shift from the traditional role of experts with answers to approaches that are supportive of people resuming personal responsibility and control even in the context of severe or disabling conditions.

The emerging ambition to adopt recovery coaching as a basic competency for all mental health workers creates obvious challenges for them and the possibility of their resistance or rejection of this change to traditional ways of working. Training and support for recovery coaching will need to be carefully managed so as to constructively engage the workforce. Careful evaluation of the usefulness and return on investment of such a new way of working and being would be essential.

Conclusions

Although coaching has been used in the sports and business world for many years, it is a relatively new concept in the medical and mental health world. For readers interested in learning more about life coaching we have included some sources and resources in Box 6). Recovery can be seen as reflecting ‘common sense’ (Reference AmeringAmering 2008), but common sense is not necessarily common practice. If successfully supporting people to make progress in personal recovery is ever to become the common purpose of mental health services (Reference Roberts and HollinsRoberts 2007), there will need to be a development of new aspects and attitudes to practice that positively support health and well-being and engage with the radical and transformational hope of empowering people who need and use services to be maximally in control of their lives. There is a broad overlap between the guiding aims, goals, values and practices of both recovery (Devon Partnership NHS Trust 2008) and coaching and an emerging, but largely unevaluated, emphasis that applying life coaching skills in the service of mental health recovery – recovery coaching – could be a key practice for the future.

BOX 6 Sources and resources for further study and training

Boyle D (2004) Coaching for Recovery. A Key Mental Health Skill. Pavilion Publishing.

Connor M, Pokora J (2007) Coaching and Mentoring at Work. Developing Effective Practice. Open University Press.

Martin C (2001) The Life Coaching Handbook. Everything You Need to be an Effective Life Coach. Crown House Publishing.

Mumford J (2007) Life Coaching for Dummies. A Reference for the Rest of Us. John Wiley & Sons.

Robbins A (2001) Notes from a Friend. A Quick and Simple Guide to Taking Charge of Your Life. Pocket Books.

Starr J (2008) The Coaching Manual. The Definitive Guide to the Process, Principles and Skills of Personal Coaching. Prentice Hall.

Zeus P, Skiffington S (2005) The Coaching at Work Toolkit. A Complete Guide to Technique and Practices. McGraw-Hill Australia.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Life coaching is:

-

a a form of therapy

-

b about advising clients

-

c based in the present and the future

-

d a relatively new concept in sports and the business world

-

e backed by a robust evidence base to support its effectiveness.

-

-

2 Coaching and mentoring are similar in that:

-

a they both bring out the best in the coachee/mentee by tapping their resourcefulness

-

b both are appropriate for time-limited sessions only

-

c both coaches and mentors have expertise in the specialist fields of their coachees/mentees

-

d counselling skills are not important

-

e both place more emphasis on the professional development of the person.

-

-

3 It is true that:

-

a the principles of recovery and life coaching are not similar

-

b promoting awareness, responsibility and self-belief is unique to a coaching approach

-

c the GROW framework is a popular tool used in therapy

-

d successful coaching outcomes rely more on the coach's expertise than coachee's motivation to change

-

e the recovery relationship is based as much as possible on partnerships.

-

-

4 Recovery coaching:

-

a cannot take place unless a person has achieved ‘clinical recovery’

-

b is a stance that only ‘recovery coaches’ need to adopt

-

c does not apply to mental health professionals

-

d is an emerging practice in wellness-oriented mental health services

-

e is about insisting that a person takes on responsibility for their life, thereby promoting self-management.

-

-

5 In recovery coaching:

-

a the focus is on the problems rather than solutions

-

b one component is identification of the person's core values and values that may be in conflict

-

c a successful coaching relationship does not necessarily have to be based on a sense of openness and trust between the coach and the coachee

-

d the coach has the right to disapprove of the way the coachee lives their life

-

e the coach is ultimately responsible for the results the coachee is generating.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | c | 2 | a | 3 | e | 4 | d | 5 | b |

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of David Cook and other members of the Recovery and Independent Living Professional Expert Group, Devon Partnership NHS Trust.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.