The word ‘monster’ derives from the Latin, monstrare, to demonstrate, or monere, to warn. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a ‘monster’ as ‘something extraordinary, a prodigy, a marvel’, and ‘monstrous’ as ‘deviating from the natural order’. In the early modern period, monsters were seen as deviations from ‘normal’ nature that could reveal God’s plan and nature’s inner workings, or singular instances that acted as omens. Monsters could take many forms. They were commonly hybrids with characteristics that crossed accepted natural boundaries. This involved exaggeration, proliferation or absences of normal body parts, such as deformed births with excess limbs or multiple heads, races of one-footed sciapodes and dramatically undersized pygmies.1

Many kinds of monsters were represented in different types of early modern publications, including cheap pamphlet literature, illustrated compendia of medical monstrosities, such as Des Monstres et des Prodiges (‘On Monsters and Prodigies’, 1573) by French surgeon Amboise Paré, and natural histories, such as the Monstrorum historia (‘History of Monsters’, 1642) of the Bolognese collector Ulisse Aldrovandi. The material, often taken from humanist works, combined several classical traditions of monstrosity. Aristotle’s On the Generation of Animals cast monsters as deviations from natural development, often through the excessive influence of the female imagination on the foetus. Cicero’s On Divination described monsters such as deformed foetuses as individual, supranatural occurrences, interpreted as prodigies or omens. Finally, Pliny’s Natural History described whole populations of deviant human forms such as dog-headed cynocephali or headless blemmys.2

These Plinian races and other monsters were often placed at the shifting margins of the known world, or ecumene, on maps, from medieval mappaemundi to early modern charts. As geographical knowledge developed with exploration and colonial activity in the early modern period, the medieval ecumene, previously bounded by impassable ocean and an uninhabitable ‘torrid zone’, was rapidly expanded. The locations of these monstrous races shifted also, retreating out of reach to the edges of maps or to the unknown centres of continents. Monsters almost always originated elsewhere, either from distant places or local but inaccessible locations.3 Such intangibility made travellers’ tales of monsters impossible to falsify, but it also explained, for some scholars, the generation of these strange creatures in nature: the extreme conditions of unknown and distant reaches of the globe would produce similarly extreme humans, animals and plants.4

Many exotic beasts that first reached Europe from the late fifteenth century were deemed to be ‘monsters’. They were often seen as adulterated or degenerate forms, inferior to God’s original creations that had populated the Garden of Eden. New World species were sometimes interpreted as Old World species affected by dramatic climates: the whiteness of the polar bear resulted from the loss of the brown colour of other bears in freezing Arctic conditions. Similarly, the startling whiteness of the ivories of walruses and elephants was produced by the extremes of the ‘coldest weather’ and the ‘heat of heaven’ in their respective regions of origin.5 Sometimes new monsters were the result of miscegenation, the illicit coupling of ‘Godly’ beasts. For example, according to some authors, the union of the tortoise and the hedgehog in Noah’s Ark had produced the armadillo.

This chapter examines how and why exotic creatures were made into monsters in early modern European natural histories. It focuses on the making of one particular monster, the bird of paradise, that arrived in Europe in the early sixteenth century as trade skins. Unlike other birds, these creatures were thought to live floating perpetually in the skies without legs or wings. The first two sections outline the reasons why new creatures had to be assembled by naturalists, and the early constructions of these spectacular birds in natural histories and cabinets. The third and fourth sections examine the dramatic reworking of these creatures in the early seventeenth century by the Flemish Professor of Botany at Leiden University, Carolus Clusius, and the patchwork nature of the images that he constructed. The fifth section highlights the long chains of exchange through which Clusius’s materials passed, though he was attempting to present ‘direct experience’ of the birds. The final two sections explore the ways in which such composite monsters could be used for emblematic functions, and how their chimerical forms made them very malleable so they could be used for different symbolic purposes.

Assembling parts

New animals and plants did not arrive in Europe as ‘monsters’; they rarely even came as complete specimens or living creatures. Rather, most were brought in as preserved or decaying objects, collected by travellers and sailors and transported for many months on merchant ships from European colonies such as Batavia or New Spain. The trade routes taken by ships were determined by practical and economic concerns, so these things rarely moved across the globe by the most direct paths. As a result, the conditions in which exotic natural objects were collected and transported were often less than ideal. Housing specimens in transit and preserving them from decay was very difficult, so the commercially valuable or most easily preserved parts of creatures were most likely to be transported, such as walrus tusks or armadillo carapaces.6

After arriving in Europe, these things entered flourishing markets for items of naturalia or circulated within the elite networks of gift exchange between scholars, collectors and patrons. Objects were displayed in cabinets of curiosity, broadcast in pamphlet literature and described in detail in more formal publications. Physical material was often accompanied by travellers’ tales of exotic natures, which contained both eyewitness information and material collected from natives in colonial locations. This information could remain closely associated with the objects, but was sometimes dissociated.7

The mutilated or incomplete forms of these specimens and the accounts of exotic beasts encouraged reconstruction by naturalists, who often had to actively assemble unknown creatures from disparate body parts and pieces of transported information. They gathered specimens from their own collections, correspondents and second-hand accounts, as well as using familiar referents from classical authorities, previous accounts and known creatures. The results were chimerical European constructions, often very different to the living animals and plants: they were actively made into things that played roles in European cosmologies. They often became ‘monstrous’, boundary-crossing or uncategorisable things, deviations that were in fact used in defining boundaries and structuring the world.8

New creatures arrived in Europe as physical objects, but it was the printed images and textual imagery relating to them that circulated most widely. New beasts existed primarily in the pages of early modern publications. The construction of one ‘monster’ offers a rich case study of such construction: the birds of paradise or manucodiata in the Exoticorum libri decem (‘Ten Books of Exotic Things’, 1605) by the naturalist Carolus Clusius. This volume was the first European work to deal exclusively with the natural history of ‘exotics’, and the extensive material Clusius presented made his book authoritative for over a century. Clusius worked on the Exoticorum intensely despite his failing health, keeping unusually close control over its production throughout the publishing process. He continued to gather new material and accounts, to be added in appendices if the relevant chapters had already been printed.9

The birds of paradise were not creatures new to Europe at the time that Clusius described them; they first appeared in printed natural histories in the mid sixteenth century. Clusius did not entirely construct these ‘monsters’ from new material, but reconstructed them into beasts very different from previous representations. Looking closely at this process of reconstruction and the details of Clusius’s account reveals the hybridity of the materials he used and the hybridity of his mode of description, which shifted seamlessly between the empirical and the mythical, literal and symbolic, objective and subjective. Using heterogeneous sources and multiple descriptive styles produced beasts that were concomitantly monstrous and chimerical.

The early history of the birds of paradise

The first examples of birds of paradise in Europe were probably five skins brought to the court of Emperor Charles V of Spain in 1522 as part of a cargo of spices and other marvels from the East Indies. These fabulous skins were shrunken and wingless as a result of preservation methods used by New Guinean tribal hunters who prepared them, causing their beaks and gorgeous plumes to be disproportionately exaggerated. Bird of paradise skins had been part of extensive Asian trade networks for at least 5,000 years before Europeans reached the region in the late fifteenth century. Europeans explored the East in search of precious commodities such as cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg, and in the hope of rediscovering the fabled Eastern ‘terrestrial paradise’. Birds of paradise were significant in Asian and Islamic mythologies and were associated with the spices with which they were traded, though the living birds were virtually unknown to anyone outside New Guinea.10

The ship’s chronicler of the voyage on which these plumed treasures had been collected, Antonio Pigafetta, described the skins: ‘These birds are as large as thrushes … legs slender like a writing pen, and a span in length; they have no wings, but instead of them long feathers of different colours, like plumes.’11

The Spanish court secretary, Maximilianus Transylvanus, wrote another, more widely circulated account of the voyage based on interviews with sailors, whose reports included Islamic Asian material:

The kings of Marmin … saw that a certain most beautiful small bird never rested upon the ground nor upon anything that grew upon it; but they sometimes saw it fall dead upon the ground from the sky. And as the Mahometans, who travelled to those parts for commercial purposes, told them that this bird was born in Paradise … they call the bird Mamuco diuata [Bird of God] …12

The first bird of paradise skins to arrive in Europe were rapidly assimilated into aristocratic Wunderkammern. Most other examples brought to Europe through the sixteenth century lacked legs as well as wings, and they remained scarce and fetched high prices on the open market.

Some ten or eleven significant scholarly descriptions of the birds of paradise were published between 1550 and 1600. An elaborate body of imagery was developed around the birds in natural histories, books of emblems, natural philosophies and other print forms: they became angelic, perpetually floating creatures that could not land, represented by bizarre dried skins to which authors rarely had personal access. These ideas were based in part on the Islamic imagery published by Transylvanus that told of the paradisial birds that never landed, as well as on their value as exotic objects traded from the East, apparently originating from a rediscovered terrestrial paradise. They were named the manucodiata, a Latinisation of the Malay name Mamuco diuata (‘birds of God’).

The legless nature of most of the skins circulating around sixteenth-century Europe was used to support these angelic images. However, it also made these birds monstrous, because they deviated from the ‘normal’ avian type as described by classical authors. Aristotle, for example, maintained that ‘no creature is able only to move by flying’, birds being two legged and winged creatures.13 The leglessness of the manucodiata was a focal point for most of the natural historical descriptions of them: these emphasised the monstrous deviation both from the expected presence of limbs and from contact with both earth and sky made by typical birds.

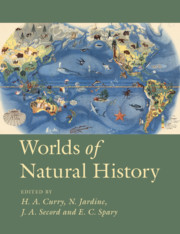

The most influential sixteenth-century account of the manucodiata was in the Historiae animalium (1555) of the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner, in which he brought together as many sources as he could acquire to form a comprehensive history of the birds. He included previous natural historical accounts as well as material from correspondents who owned skins. A contact in Padua described the small plumed birds found in the Indies that he thought might well be the rhyntace of Plutarch or phoenix of Herodotus. Another correspondent in Augsburg sent a report and image of his specimen, which Gessner used to produce a woodcut (Figure 6.1). Gessner discussed the Islamic imagery and ideas about the life histories of the birds, such as the possibility that they were kept effortlessly suspended by their haloes of plumes.14

Figure 6.1 ‘Manucodiata’. Illustration from C. Gessner, Icones animalium (Heidelberg, 1606), p. 20. This woodcut of a legless bird of paradise skin was produced after a specimen owned by an acquaintance of Gessner’s in Augsburg.

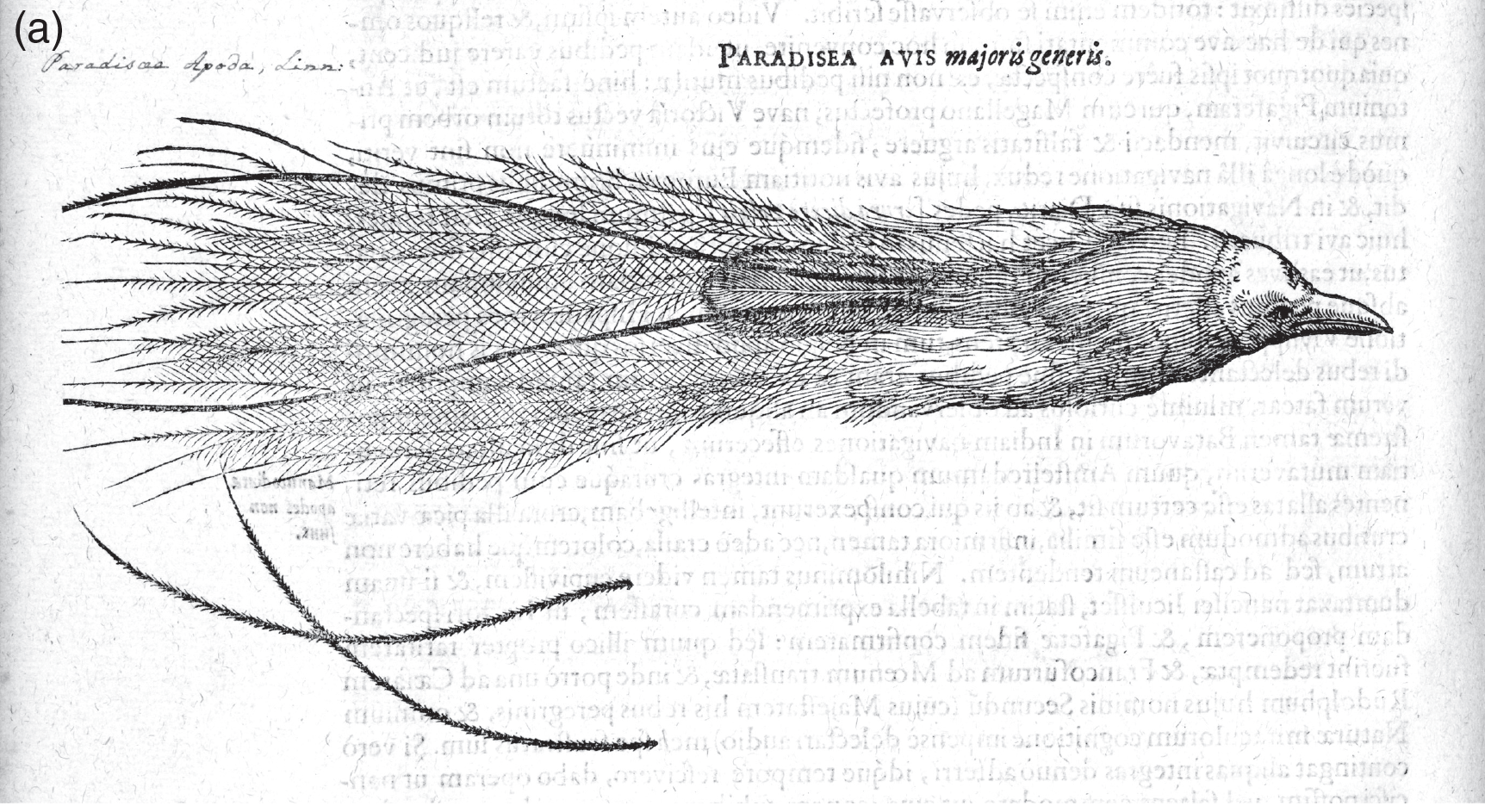

The most extensive treatment of all of the available information on the legless manucodiata was Ulisse Aldrovandi’s Ornithologiae (1599). Aldrovandi had several skins in his collection, and differentiated four species of manucodiata, each depicted in woodcuts drinking dew and floating amongst clouds. However, Aldrovandi argued that the birds could not possibly live on dew alone and conjectured that their ‘sturdy beaks’ were ‘very fit to strike insects’.15 This natural historical imagery was widely used in other print genres, most notably in books of emblems, such as Joachim Camerarius’s Symbolarum et emblematum (Nuremberg, 1596) (Figure 6.2). The birds, with their perpetual motion, were emblems of spiritual ascension, lofty thinking and restless, mercurial thought.

Figure 6.2 Emblem showing a bird of paradise accompanied by the adage ‘Terre commercia nescit’. J. Camerarius, Symbolorum & Emblematum centuria tertia (Mainz, 1668), XLII, p. 86.

Remade monsters in the Exoticorum

Carolus Clusius’s Exoticorum libri decem was produced at the same time as the balance of European power shifted in the East Indies. Whereas in the sixteenth century there had been a crown-led Portuguese and Spanish hold on spice trading, in the seventeenth century the commercially financed operations of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC), chartered in 1602) took prominence.16 The VOC commissioned voyages to take stock of the natural capital in these areas as part of its colonial operations. As a result, northern European towns such as Amsterdam and Enkhuizen became centres of accumulation for material from Southeast Asia. These Dutch expeditions to the Indies brought more bird of paradise skins to Europe, some of which still had their legs attached. They were accompanied by reports of accounts from Malay traders of how the New Guineans prepared the skins.

In 1601, Clusius heard of bird of paradise skins with legs that had arrived in Amsterdam, but was frustrated in his attempts to see them. They had been rapidly sold to one of the richest and most prolific collectors of the day, Rudolph II, for his fabulous collection in Prague.17 Clusius had to obtain assurance from the broker of the specimens, Johan de Weely, that the skins had possessed legs. This information caused Clusius to hurriedly produce a section on the manucodiata as a last-minute appendix. He admitted that he had, presumably like the majority of his well-educated readers, held the ‘erroneous opinion’ that the birds lacked legs and that Pigafetta’s account was false, as informed by reputable sources such as Aldrovandi and personal experience of seeing legless skins. He was now convinced, however, on the strength of new material, that the birds of paradise did possess legs.18

This first-person shift in opinion framed Clusius’s account of the birds of paradise. As he displayed the particulars that convinced him of a changed perspective, he simultaneously constructed a new natural history of the birds, weaving different types of sources together within the narrative of his own quest for knowledge. Presenting accounts as if from direct, first-person experience was a method commonly used in travel narratives in the early modern period. The style of ‘autoptic’ narratives lent veracity to otherwise potentially unreliable sources such as travel tales.19 Similarly, the autoptic presentation of Clusius’s account facilitated his refashioning of the manucodiata into his own, legged monsters to present to the reader, using diverse modes of expression and sources that were not always quite as he presented them. He was creating something new by skilfully crafting heterogeneous materials into things that were at once empirical and also potent emblems.

Assembling the manucodiata

Clusius began by referring to the philological history of the birds, in the tradition of Renaissance natural histories, but in a truncated fashion. He reiterated that the manucodiata were ‘unknown to the ancients’ and described by many recent authors. He referred specifically only to Aldrovandi’s account, praising it as the clearest work on the birds. This was not a commentary or reworking of old material; Clusius quickly shifted to set himself in opposition to these previous works, writing that Aldrovandi and ‘all the rest who have talked about this bird … judge it to lack feet’.20 Though he was providing evidence against the leglessness of the birds of paradise, this monstrous feature still acted as the focus of Clusius’s account. It was a point of contention: the presence of legs, as the inverse of the abnormal state, in itself became monstrous. These were exotic creatures that had transgressed the traditional attributes of being a bird, and this monstrousness remained, despite the addition of legs.

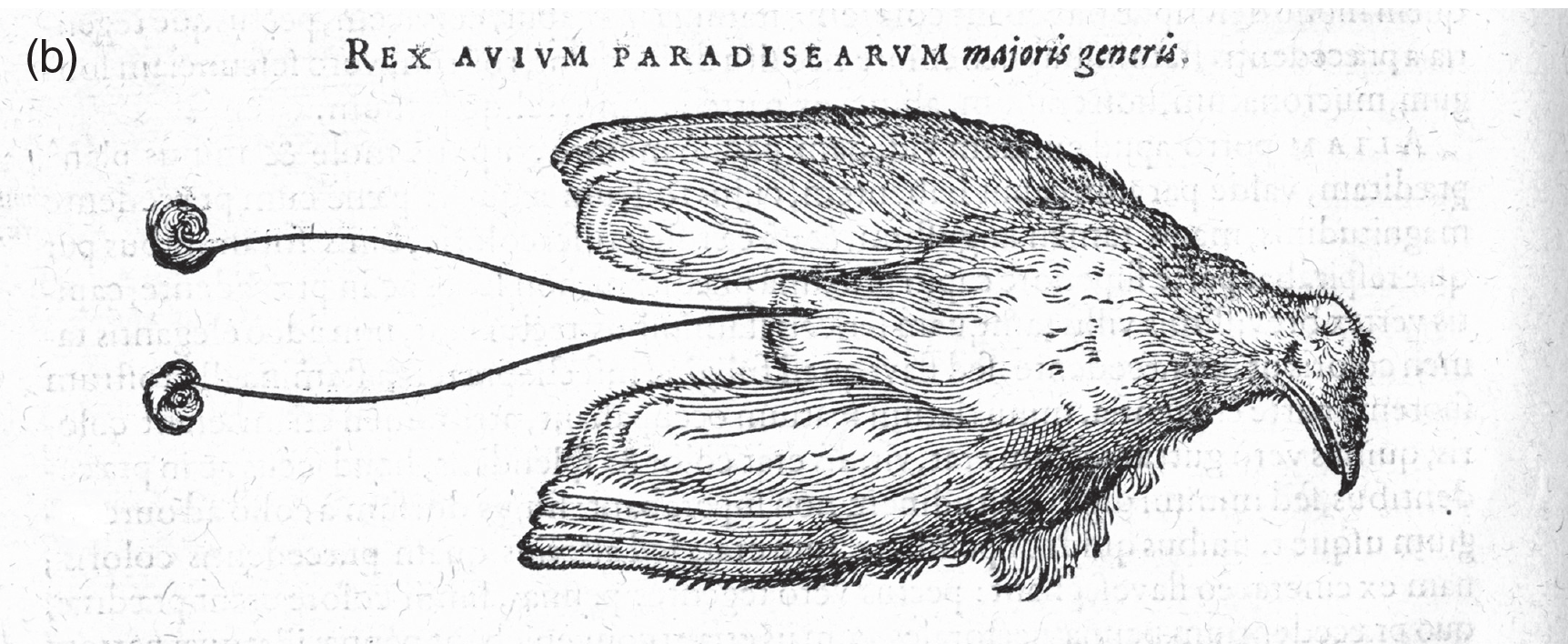

Like Gessner, Clusius drew on his wide correspondence network to gather material on the birds. This included figures from a wide range of geographical locations and social strata, from colleagues at Leiden University, collectors and scholars further afield, to dealers in naturalia, merchants and sailors. The scholarly correspondence networks through which objects and information moved and were exchanged were a central feature of natural history in this period, and Clusius had an especially extensive set of connections from diverse social backgrounds. In particular, he had close contact with several naturalists, scholars and collectors who actively helped him to gather material. Using a specimen owned by his colleague, Pieter Pauw at Leiden University as well as a specimen of a new kind of bird of paradise, a ‘king bird’, owned by Emmanuel Swerts, Clusius could write first-hand descriptions of specimens and have plates produced for the Exoticorum (Figure 6.3).

Just as exotic objects stood in for experience of distant places that could not be experienced, certain kinds of description could stand in for experience of unseen objects. About a third of Clusius’s account was taken up with the painstakingly detailed depictions of these two specimens, using rich and vivid language:

From the throat right up to the breast, the feathers … [are] saturated with green colour so elegant and splendid, as in the throat of a wild male duck, that none more elegant may be seen; the feathers covering the breast are very fine, but long and very soft, of a dark rufous colour, looking like nothing so much as silken threads …21

His words made readers into ‘virtual witnesses’ of these physical objects. Giving ‘vivacity’ to an account through copious descriptive details was another important way to imbue a text with the impression of reality, like the autoptic perspective. A variety of descriptive techniques, such as enargeia (vivid verbal recreation) and ekphrasis (lively description of visual objects), were drawn from classical scholarship and were used both to imply credibility and to give a description with a lifelike quality. Such description was used in many other types of text and was an especially distinctive feature of travelogues, whenever the aim was to convey the credible experience of something absent.22

Such ‘painting’ with words was a powerful rhetorical tool that transmitted not only the visual impression of something but also the subjective experience of it to the reader, by communicating the effect of viewing the object on the writer. Aside from describing their beautiful plumes, Clusius repeatedly stated how the ‘form of the bird’, even as a mutilated skin, could engender ‘infatuation’ in the viewer. In the early modern period, visual experiences of things could create ‘wonder’, either because of their mode of display, as in the Wunderkammer, or the mystery of the objects themselves.23 Clusius’s description of these specimens, while empirical, was also a way of making these birds into ‘wonders’ that could evoke awe and amazement in viewers.

Such language gave the impression that the skins were supranatural objects, beyond the ordinary creations of nature. They were not only vividly coloured, with feathers of ‘blood red’, ‘dark black’ and ‘golden’, but they also seemed almost artisanal creations, from materials like ‘silken thread’ and ‘shoemaker’s cord’. Blurring the boundaries between the natural and artificial was a popular motif of early modern curiosity collections, which often contained objects such as nautilus shells set in elaborate metalwork, or gilded Seychelles coconuts. The interplay between divine creativity and the artisanal expertise of man was a great source of fascination. Many other kinds of ‘monsters’ in collections, such as ‘dragons’ formed from artfully dried rays or ‘mermaids’ made from joining various animal body parts and other materials were also popular: part deceptions, part playful jokes.24 Clusius’s manucodiata description played on this aesthetic elision between art and nature, and evoked their exoticism. They were still monstrous wonders from the East, even if not the perpetually floating creatures previous naturalists had described.

Chains of exchange

It was a cruel irony that Clusius never saw a bird of paradise skin with its legs on. Indeed, in order to show the erroneous nature of previous naturalists’ interpretations of mutilated legless skins, and to make a truth-claim about the legged state of the birds, he had to assemble a chimerical legged bird himself. Critically, though he used the legless specimens as physical tokens to represent the legged creatures he was constructing, the verbal images of these specimens stood for the experience of the examples he had not seen himself. He only had second-hand accounts of legged specimens, from de Weely and sailors from the voyage bringing them to Europe. In his letter to Clusius, de Weely described how:

The bird of paradise was in every respect like the vulgar sort, somewhat flat … it had two large feet like those of a sparrow hawk or harrier, that looked unseemly and ugly … The leg was dried and looked ugly too, so that the Indians very sensibly cut off the feet together with the leg, for it is the ugliest part of the bird, and in my opinion they all have similar feet.25

This second-hand description was Clusius’s only assurance that what he had heard about the legged state of the new skins was true. He relied on the good faith and expertise of de Weely as assurance that the knowledge he imparted was reliable.

Clusius rejected the Islamic imagery assimilated by other authors from the first voyage bringing bird of paradise skins to Europe but did use accounts from sailors. These contained information several times removed from direct sources, and would not usually have been deemed ‘trustworthy’ reports by early modern scholars: ‘I am assured that the sailors who brought back these words, though they have not visited the islands in which those birds are born and live, understood from those from whom they purchased them that all are endowed with feet and walk and fly like other birds.’26

The sailors’ accounts led Clusius to include a new set of tales about the birds of paradise. This was the idea of the ‘king bird’, which was seen to lead the other birds, ‘thirty or forty in flocks’. Such was their loyalty to ‘their King or Captain’ that if it happened ‘to be killed or fall down, the rest that are in the flock fall with him, and yield themselves to be taken, refusing to live’. The greater and lesser birds of paradise each had their peculiar ‘King’. The ‘Lesser King’ was black and ‘less handsome’, the ‘Greater King … was a very rare one’, a ‘little bird’ and brilliantly coloured. 27

Clusius also included material that he probably acquired from the unpublished diary of Jacob van Heemskerck, who captained the first Dutch voyage to the Indies from 1599 to 1601. Heemskerck relayed information, from an Ambonese captain, that the birds of paradise were hard to find, located only on certain islands, and only flew in certain winds. Natives of the places where the birds dwelt caught them by trickery: hunters waited until after one bird had ‘tasted’ the water from a pool and shown it to be safe for the other birds, then poisoned the water to catch the flock that descended to drink.28 Clusius related this information with the proviso that it was a ‘fable’, yet he still included it, making it part of the new images of the birds. While rejecting earlier travellers’ images of the manucodiata, Clusius incorporated a new set of travellers’ tales into his own version of the creatures.

Colonial monsters

Monsters often had long lives as they circulated between different publications. That Clusius was simply making new monsters even as he appeared to ‘normalise’ them becomes clear when considering the fate of the legged birds of paradise. Clusius’s new imagery featured in subsequent seventeenth-century natural histories, developed further and repurposed for specific symbolic roles. In particular, the birds he depicted acted as an image of the East, not as a bountiful paradise as they had in the sixteenth century, but of the increasingly problematic colonial interactions there. Monsters were often used to embody shifting European relationships with distant places and peoples. Colonial locations such as Southeast Asia were regions both full of promise and full of potential danger, commercially lucrative and politically fraught. The natural historical constructions of exotic plants and animals from such locations were loaded with meaning.

In the Historiae naturalis et medicae of the VOC physician Jacobus Bontius, the birds of paradise were described as sturdy-legged birds of prey, quite unlike the angel-like entities in sixteenth-century natural histories:

Birds of paradise, formerly considered by many to have no legs, are found here abundantly … It is untrue, however, that those paradise-birds have no legs, or feed on air, as they hunt small birds, like finches, with their curved, sharp nails and devour the same immediately, like other birds of prey, and it is untrue that they are only found when dead, for they roost on trees and are killed with arrows by the natives.29

Similarly, in the Ornithology (1678) of Francis Willughby and John Ray, the birds of paradise were rapacious carnivores with fierce talons, classed with the ‘cowardly and sluggish, lesser and exotic’ rapacious ‘land birds’. The contentious legs became the defining feature of the new birds of paradise, as monstrous hunter’s apparatus.30 These depictions placed even more emphasis on the legs of the manucodiata than Clusius had done: they turned the legged birds into emblems of colonial conflict. The new interpretations of the birds’ physical form, nature and place in creation were linked to and symbolic of changing European relationships with the birds’ region of origin.31

Even from the sixteenth century, the birds of paradise had represented the riches to be gained in the Indies: ‘The golden birds that ever sail the skies’ described in the Os Luciadas (1572) of the Portuguese poet Luis Vaz de Camões symbolised the riches of the exotic southern regions in the Pacific. The ruthlessly mercenary interests of the Portuguese and Spanish ships reaping spice harvests were echoed by de Camões’s description of the birds of paradise:

The shift from footless and angelic images to legged and carnivorous creatures can also be tied to the changing European image of the Indies from a fabled paradise to that of an infernal and hostile region. Contributing to this were violent encounters with native peoples resulting from explorations around the ‘Southland’.33 The cosmological fall from grace implied by becoming legged, terrestrial birds, no longer the angelic creatures perpetually floating in the heavens, was mirrored by a shift in the way that the birds’ region of origin was perceived.

Depictions of the legged manucodiata reflected the increasingly complex and ambivalent colonial relationships in the Indies through the seventeenth century. Attempting to monopolise Moluccan spice production in the late seventeenth century, the Dutch systematically destroyed whole islands of clove trees: commercial success rested on battling an intractable exotic nature as much as political control. These measures caused considerable bloodshed and destruction of the spice production in some Moluccan islands. The VOC’s spice trading venture came to involve increasing violence and antagonism with local populations as tensions rose, though it remained profitable until the end of the eighteenth century. Bontius’s sturdy-legged manucodiata, that could ‘tear and devour’ other birds with their ‘crooked and very sharp claws’ came to signify a region that was no longer impossibly bountiful, but dangerous and threatening.34

Myriad monsters

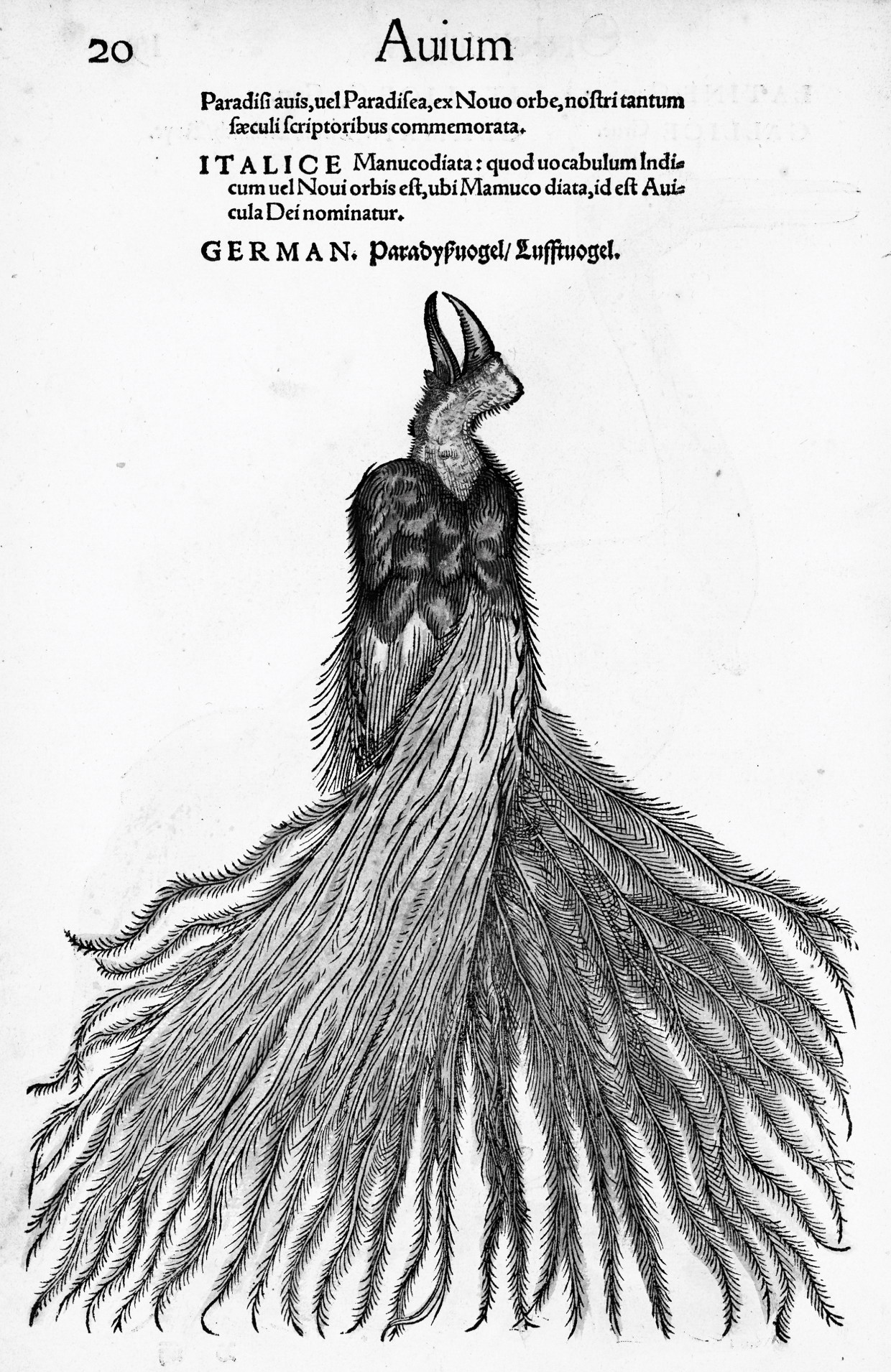

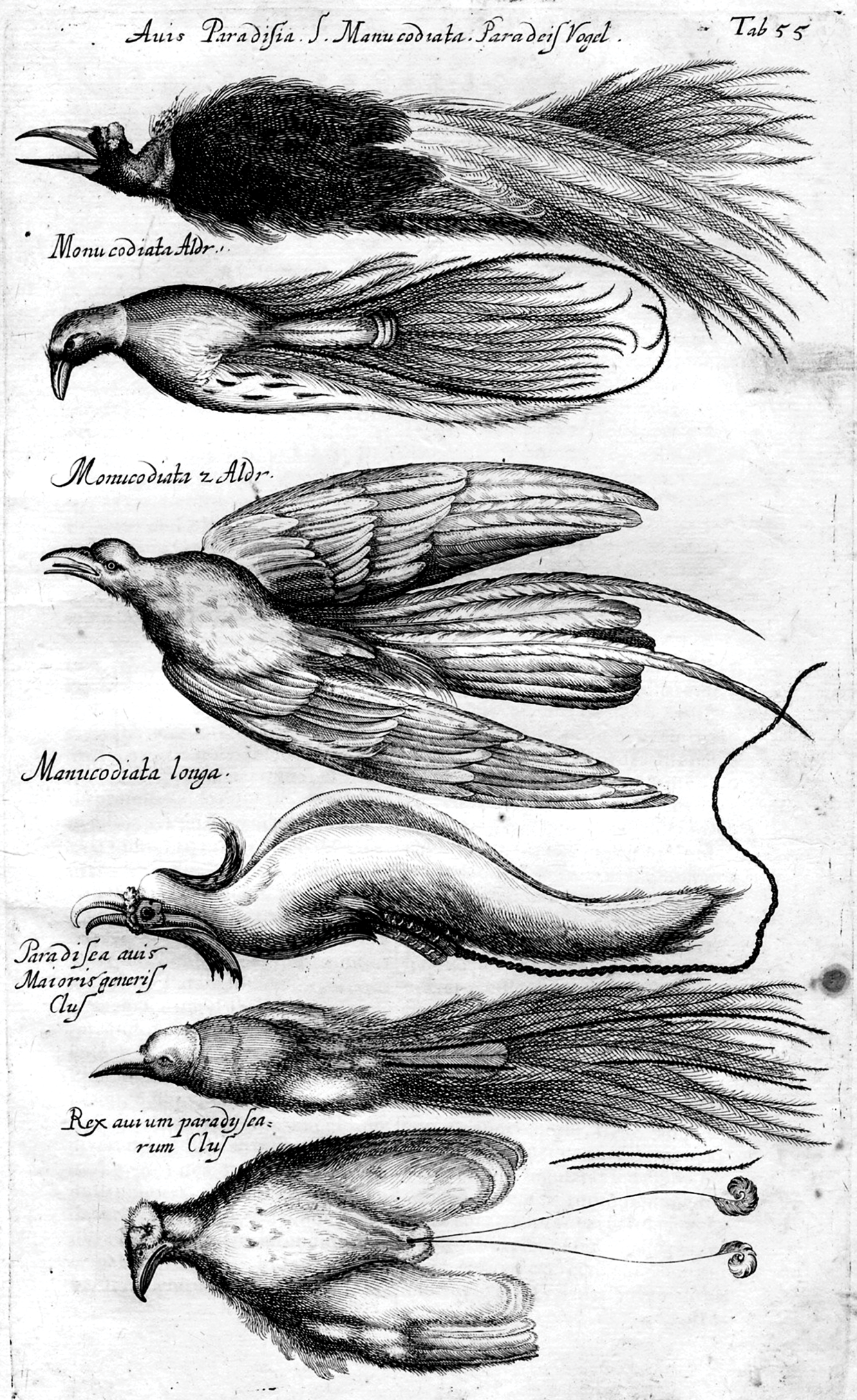

Monsters often existed in plural forms in print and images, they were malleable and they served multiple purposes. An important demonstration of the hybrid and emblematic nature of European images of the manucodiata is the fact that the images of legless birds did not disappear. The ideas of earlier naturalists, described and dismissed by many authors, were not rapidly or indeed universally rejected. Even well into the seventeenth century the nature and form of the manucodiata were debated in natural histories and collection catalogues, such as Jan Jonston’s Historiae naturalis (1657).35 The printed images in the works of Gessner, Aldrovandi and Clusius were all used to represent the birds in later natural histories, including Jonston’s, as well as in many other genres of publication, such as books of heraldry, theological pamphlets and books of mirabilia (Figure 6.4).

Figure 6.4 Various birds of paradise, after C. Gessner, Historia animalium, U. Aldrovandi, Ornithologiae hoc est de avibus historia and C. Clusius, Exoticorum libri decem. J. Jonston, Historiae naturalis, de avibus libri VI (Amsterdam, 1657), tab. 55.

The persistence of these printed images was both the result of the symbolic value of the things they depicted, and the desire of printers to save money on producing new plates for publications.

Similarly, while depictions of birds of paradise in artists’ images shifted in parallel with natural histories, especially in northern Europe, this was by no means ubiquitous. For example, the birds were shown, legged and winged, with other terrestrial birds in paintings such as Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder’s The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (c.1615).36 Yet many painters depicted the birds as floating, angelic creatures, as in Roeland Savery’s Landscape with Birds (1627).37 Even when made terrestrial, the birds of paradise were set in Edenic scenes, amongst other ‘birds of Eden’ such as the hoopoe, as in Frans Snyder’s Concert of the Birds (1629).38

There were multiple emblematic roles for the birds of paradise, and they existed in multiple forms, both in natural histories and across other media. Just as the physical objects existed with and without legs in different collections across Europe, a variety of virtual manucodiata existed in Europe. How the birds might be represented depended not only on the empirical experience of an author or the specimens to which they might have access, but on the other pieces of imagery and information they used to construct their account, and, crucially, on the underlying aims of the author.

Conclusion

Exotic monsters did not arrive in Europe; rather, they were made, often by naturalists such as Clusius. Highlighting the potential monstrosity of new beasts was both a way of dealing with problematic or shocking characteristics and a way of accentuating their worth, because monsters were commercially valuable things. As a result, the number of monsters grew rapidly in the early modern period. Once constructed, virtual representations of new beasts, especially monsters, circulated far more widely than specimens could do.

What Europeans defined as monstrous or not was determined by what was included within the known and familiar and what was excluded. The geographical marginalisation of monsters therefore echoed the inherently marginal nature of monstrosity itself.39 They were things that bridged geographical distances between Europe and unseen exotic regions, just as natural historical descriptions mediated between readers and unseen objects.

The presentation of new beasts was closely intertwined with the presentation of the author themselves. The Exoticorum presented Clusius as an arbiter of the exotic and purveyor of new knowledge and new monstrosities. In remaking the manucodiata, Clusius distanced himself from earlier encyclopedic accounts such as Gessner’s, presenting his material as if from personal experience, to produce a specific, new image composed of discrete tropes.

Yet in practice, Clusius’s text was less distinct from older texts like Gessner’s than it appeared. His array of sources also included previous natural histories, personal observations and indirect accounts that had passed through long chains of exchange. The relationships between the empirical and emblematic, objective and subjective in Clausius’s work were certainly similar to those in Gessner’s. The textual conventions of natural histories, even the most erudite ones, were far more fluid than is usually assumed by historians.40 In particular, the chimerical natures of the beasts depicted in these natural history texts mirrored the chimerical patchwork of the texts themselves.