Michael Ondaatje (Fig. 1) – perhaps most famous for his novel The English Patient (1992) – was born in 1943 in Kegalle, Sri Lanka (Reference SpinksSpinks 2009). He was the middle of three children, born into a well-to-do colonial family. Ondaatje’s parents divorced when he was 2 years old and the family (without his father) emigrated to London. Michael

Ondaatje moved to Canada in 1962, where he currently lives. Ondaatje’s father, Mervyn, had chronic alcohol problems and squandered much of their wealth (Reference SpinksSpinks 2009). He developed increasingly erratic behaviour, including an episode when he commandeered a train at gunpoint, instructing the driver to shunt backwards and forwards, before stripping naked and hiding in a tunnel. In the poem Letters & Other Worlds, Ondaatje says of his father, ‘He came to death with his mind drowning’ (Reference OndaatjeOndaatje 1989). I mention his father as there are perhaps echoes of Mervyn in the protagonist of Coming Through Slaughter.

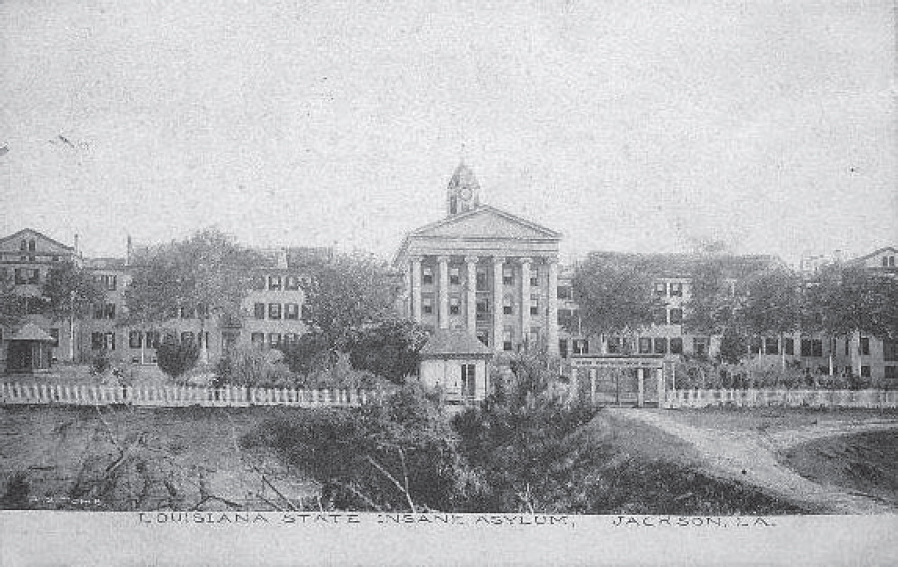

In the 1970s, Ondaatje’s curiosity was caught by a short article about the early jazz musician Buddy Bolden (1877–1931), which stated that he ‘went berserk in a parade’ (Reference SpinksSpinks 2009). Ondaatje travelled extensively in Louisiana to research Bolden, visiting the East Louisiana State Hospital (Fig. 2), where Bolden spent the last 25 years of his life (Reference MarquisMarquis 2005), and Slaughter, a small town near the hospital. He found a paucity of reliable information about Bolden.

FIG 2 East Louisiana State Hospital, formerly Louisiana State Insane Asylum. Image courtesy of AsylumProjects.org.

Coming Through Slaughter

Coming Through Slaughter was first published in 1976. The novel is a recreation of Bolden’s life, told in a series of fragments. These consist of pieces of narrative; extracts of interviews and hospital notes, some imaginative, some apparently real; lines of jazz lyrics; and improvised passages that blur poetry, jazz and fact.

The early part of the book portrays Bolden’s lifestyle and character – an intensely lived life, walking his children to school in the morning while telling them jokes, working as a barber during the day, then playing jazz ‘on into the night and into the blue morning’ (Reference OndaatjeOndaatje 1984: pp. 10–14). He is shown to drink heavily. A ‘patron’ gave him ‘two bottles of whiskey a day’, and when drunk he would ‘cut hair more flamboyantly’. It is stated, as if picking up gossip, that ‘many interpreted his later crack-up as a morality tale of a talent that debauched itself.’

FIG 1 Michael Ondaatje.

Photo credit: Jeff Nolte.

A strange side to Bolden emerges in the middle of the book. While he is cutting the hair of a friend, Tom Pickett, he starts attacking Pickett with a razor. His motive is unclear, but later it seems that Bolden thought Pickett was having an affair with his wife. Shortly after the attack, Bolden disappears and does not return home for 2 years. One of his friends worries, ‘He’s not safe by himself, he’s got lost’ (Reference OndaatjeOndaatje 1984: p. 15). During this period, told to us in fragmentary glimpses, Bolden appears to withdraw from society, with his experience of the world at times seeming distant, at one remove. There is an odd incident where he is about to board a train for home, but we later realise that he is hiding behind a wagon. After this, he appears to neglect himself, living on the streets and enraptured by his thoughts, which centre around imagining playing the cornet perfectly. He is described by friends as bizarre and erratic and as ‘swimming towards the sound of madness’ (Reference OndaatjeOndaatje 1984: p. 69): compare this with Ondaatje’s father Mervyn, who ‘came to death with his mind drowning’.

The last section of the book is quieter and Bolden’s perception of events becomes increasingly dulled and distorted. In the asylum, during an attempted escape of a fellow patient, Bolden sits in his chair, not responding to calls.

FIG 3 The Bolden Band in 1905. Buddy Bolden is standing second from the left. (Courtesy: The Historic New Orleans Collection.)

Psychiatry’s reading of Bolden

Bolden has evoked the interest of a number of psychiatrists and psychologists. In a paper titled ‘Dementia praecox and the birth of jazz’, the psychiatrist Sean Reference SpenceSpence (2001) postulated that cognitive and motor impairments associated with schizophrenia may have influenced how Bolden improvised on the cornet (Fig. 3.). Ferdinand Jones, an American psychologist, analysed Bolden’s history, concluding that ‘alcohol and a destructive mental process were the likely causes of Bolden’s psychological troubles’ (Reference Jones and JonesJones 2000). Bolden’s biographer Donald Marquis interviewed the superintendent of East Louisiana State Hospital, Lionel Gremillion, who had reviewed Bolden’s psychiatric notes. Gremillion thought that Bolden would have had ‘manic depressive psychosis or [would have been] paranoid schizophrenic’ (Reference MarquisMarquis 1971).

A personal reading of Coming Through Slaughter

What was most striking to me as a reader of Coming Through Slaughter was how I was left with a strange mixture of bewilderment and conviction about the reality of Bolden’s experience. The narrative’s refusal to comment on where sense is lost, or even to acknowledge it, helps conjure this experience in the reader. Also, fragments of the novel which are stranger, or in which Bolden appears to be mad, are often juxtaposed with clearer writing. The contrasts of different textures create an experience for the reader – the reader is not allowed into the role of an observer who can make sense of things.

The narrative’s refusal to comment on when sense is lost is shown in the following extract (Reference OndaatjeOndaatje 1984: p. 78), which occurs after Bolden’s attack on Pickett:

‘Bolden imagined it all, the wet deceit as she hunched over him and knelt down under him or drank him in in complex kisses. The trouble was you could see all the way through Pickett’s mind, and so the moment he had said he had been fucking Nora Bolden believed him. In the very minute he was screening his laughter against Pickett’s fantasies he believed him. Tom Pickett didn’t have the brain to have fantasies.’

Bolden believes, possibly delusionally, that his wife (Nora) has been unfaithful with Pickett. The absence of any comment or questioning in the narrative about the truth of the matter injects Bolden’s panic into the reader. The lack of any punctuation or link between the words ‘Nora Bolden’ means we have to read the sentence again to follow what is happening – this brings the reader alongside Bolden to experience something of the same slipping of connections.

As a further example of where the narrative refuses to acknowledge or comment on its strangeness, here is Bolden looking at his hands as he is taken to the East Louisiana State Hospital: ‘Blue necklace holding my hands together’ (p. 139). Presumably he is handcuffed – but this is not our initial perception.

The following quotation shows Bolden trying to explain what has happened after an operation on his neck to repair ruptured blood vessels:

‘Wet in my neck. Teasel in my neck. You see I had an operation on my throat. You see I had a salvation on my throat. A goat put his horn in me and pulled.’ (p. 139)

Somehow Ondaatje carries us along with the feeling that it makes sense – there seems to be a connection between ‘operation’ and ‘salvation’ besides pure rhyme. It is hard to pin down what this is – but it made sense when I read it.

The effect of the contrasting textures is illustrated by putting the first extract, ‘Bolden imagined it all…’, in context. This section is juxtaposed with crystal-clear writing, almost reportage, such as:

‘For a while after that Frankie Dusen the trombonist took over some of Bolden’s players. They called themselves the Eagle Band. Bunk Johnson, seventeen years old, took his place.’ (p. 80)

The contrast gives the first extract a peculiar lighting, somehow leaving the reader wondering whether it really happened.

Here is the short poem Train song (Reference OndaatjeOndaatje 1984: p. 85) from the middle of the book, in which Bolden watches landscape go past:

To put this poem in context, earlier in the book Ondaatje builds up a layer of poetic interludes, which previously were punchy and unambiguous, consisting of what seem like extracts from jazz lyrics, or terse names of songs. So when we read this poem at this point in the book, as well as the rhythms of being on a train, one experiences a gradual dissolution of sense as the possible connections between words are explored. As explained by Lee Spinks, lecturer in English at Edinburgh University, as the novel progresses, the relationship between words becomes increasingly distant, and in places the only connection may be the coincidence of sounds between otherwise unrelated words (Reference SpinksSpinks 2009).

In the final section of Coming Through Slaughter, the reader experiences Bolden’s progressive withdrawal, and perhaps cognitive impairment. Quotes from much earlier in the book, from a younger period in his life, are reused, but in a transformed context. For example, ‘if you don’t shake, don’t get no cake’ (p. 23) is part of an early energetic sequence of what seem to be jazz lyrics, alongside other brief interjections such as ‘Alligator Hop’ and ‘2.19 took my babe away’. However, in this final section, surrounded by an account of rape by the ‘guards’ at the asylum, the same phrase is used again (p. 146), but it takes on a completely different association. To the reader it conveys a distant flicker of memory, an attempt to make sense of what is happening through what remains intact in Bolden’s mind. The transformation of an energised jazz lyric into a formula of submission is affecting.

Conclusions

I do not think that Coming Through Slaughter romanticises mental illness, though certainly much of the writing is beautiful. I have neglected in this article Ondaatje’s exploration of the creative impulses in Bolden, the imaginations of what inspired his music. What amazes me about the novel is the seamless blending of different kinds of experience together into one coherent person. There are no clear lines between periods of lucidity and periods of illness – rather like the slip from reading music to improvising.

Ondaatje leaves us with the confusion without interpreting it, without delineating for us the boundary between coherence and incoherence. And this, I think, projects powerfully into us Bolden’s raw experience, uncontained and unprocessed.

This struck me as a new experience, and one relevant to psychosis. While I have had the experience of becoming lost in a place I shouldn’t have been, this book got me thinking about a different type of experience, one harder to tap into from the everyday. Bolden’s unravelling of reality lacks the insight of being lost – it is at the same time utterly convincing yet bewildering.

In writing this article, I became aware that I have been trying to work out how this sense of un-understandability is created, and that there is a certain paradox here – this trying to force something into making sense is precisely what Ondaatje is avoiding. It is really an experience reading this book.

How do I know that this experience is analogous to the experience of psychosis? Of course, without having experienced psychosis, I cannot be certain. However, this book certainly seems to go into the right territory. Coming Through Slaughter evoked in me a new and vivid experience, which I did not begin to question and find strange until I put the book down. In this, I find it a helpful insight into a psychotic experience.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.