INTRODUCTION

In March 2020, COVID-19 came to my hometown, Aligarh, India, where my family still lives. Aligarh is a typical town in India's most populous state, Uttar Pradesh, and the majority of Aligarh's residents are Hindu. Conflict between Hindus, who make up 80% of the country's population, and Muslims, who constitute the country's largest minority at 14%, has been present throughout India's history. India is a secular democracy that believes in the separation of religion and state. Muslims have long faced social and political marginalization, but fault lines between the groups have deepened, particularly since the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power under Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2014. In the years since, violence and attacks against Muslims have increased. The coronavirus has added fuel to the fire, presenting Hindu nationalists with a new opportunity to suppress and harm minority groups.

In a deeply divided and striated country such as India, language is best understood as being part of, dependent on, and as a reinforcer of religious, ethnic, class, and caste-based structures. And in times of crisis, language may also mirror societal chaos and fault lines. The COVID-19 crisis was one such moment. As India came to terms with the disease, the coronavirus’ impacts on different populations exposed and widened long-standing social divisions. By studying communications from the early days of the pandemic in India, we can see how a society's language reflects, shapes, and reinforces meaning, social hierarchies, and marginalization.

The first news reports of a novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China, began to surface in November 2019. By mid-March 2020, the World Health Organization had declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Italy, Spain, and France reported tens of thousands of infections and deaths. As the virus swept across the world, so did fear. India is one of the most densely populated countries in the world with 1.3 billion people. With its rapid spread and easy transmission, the fear was that the disease, if unchecked, would certainly lead to catastrophic suffering and loss of life.

On March 12, 2020, India's central government announced a prohibition of large public gatherings. The next day, the Tablighi Jamaat, an Islamic missionary movement, began a three- day, international conference in New Delhi attended by more than 1,400 people. Within days, as the number of positive coronavirus cases and deaths skyrocketed in New Delhi and in many other parts of the country, Hindu nationalists blamed all Muslims for deliberately spreading the virus.

The response to the Tablighi Jamaat incident stands in stark contrast to the deaths of a well- known Hindu businessman from Aligarh and his mother.Footnote 1 The businessman died of complications caused by coronavirus on May 12, 2020. Within a day or so, it was found that his mother had passed a few weeks earlier, and that he and his family had held a Hindu death ritual and feast for her called terahvi (or terahi) to mark the thirteenth and final day of mourning.

Reports on the number of people who attended vary wildly from one hundred to several thousand; the terahvi occurred during the nationwide lockdown and clearly violated city and state-issued orders against gatherings. Once news emerged that the businessman had come in contact with many people during the ritual and later died of coronavirus, several prominent people in the city were quarantined and a First Information Report (the first step in a criminal investigation) was filed against 150 people in Aligarh and Lucknow,Footnote 2 the capital of Uttar Pradesh. By May 20, one hundred and sixty-six people had been found to be infected due to the terahvi. The incident was reported by major national newspapers, but there were no calls for banning Hindu death rituals or questioning of the loyalty of the specific caste that the businessman belonged to. There were no hashtags like #banterahvi or #hinduterrorism or #saveindiafromhindus. There were no social media memes questioning the loyalty of all Hindus towards India. No central or state government officials made disparaging statements about Hindus in India. Unlike the language in coverage of the Tablighi Jamaat, coverage of this incident was factual; it was not about judging or defining the cultural identities of the alleged perpetrators.

In a televised speech on March 22, Prime Minister Narendra Modi asked all Indians to observe a one-day, stay-at-home event called janta curfew ‘curfew by and for people’ on March 24. He also asked citizens to honor and thank India's essential workers by standing on their balconies at 5:00 p.m. on the day of the curfew and ringing ghantas ‘Hindu ritual bells’ or banging on pots. By all accounts, the janta curfew was considered a success: many Indian roads were emptier than usual, people stayed indoors for the most part, and many came out on their balconies. The language of this speech was unifying, inclusive, and conciliatory; it stands in sharp contrast to another national address made by Modi on April 2.

On March 25, in an address watched by 197 million people,Footnote 3 Modi declared an immediate, hastily organized nationwide lockdown for the next twenty-one days. All travel by trains, buses, and cars was suspended. Overnight, as India's massive public transportation system was shut down, millions of migrant laborers were out of work and stuck in place—many of them hundreds of miles away from home. A new crisis unfolded as the lockdown forced migrant workers to start walking home on foot in blistering heat with no food, water, shelter, or money. A shocked India looked on as empty highways teemed with the faces of millions facing extreme poverty, starvation, disease, and death. Their suffering exposed painful realities of India's social hierarchy and forced India to acknowledge and come to terms with the treatment of migrant workers.

By early April, as the virus swept through India, Hindu nationalist hatred of Muslims in the wake of the Tablighi Jamaat was also exploding in the media and on social media. Not only were Muslims blamed for the outbreaks, but they were also blamed for the chaotic lockdown. In a national address made on April 2, two weeks after the janta curfew, Modi was silent on Muslims and migrant workers and made no attempt to quell Hindu nationalist outrage. Instead, he spoke about the country being led from darkness into light. Further, he referenced Hindu religious texts and asked citizens to light nine diyas (oil lamps used in Hindu religious rituals commonly found in middle and upper-caste Hindu homes) at 9:00 p.m. on April 9. In this carefully crafted speech that assumes a Hindu voice and identity for all, Modi employs several linguistic tricks—silence, othering, and dog whistling—to speak loud and clear to a receptive audience about his vision of a new majoritarian Hindu India. Modi's language defines the ideal citizen as upper-caste Hindu and affirms their sense of belonging, identity, and worldview. At the same time, his language clearly exposes the fault lines and vulnerabilities of India's society: by concealing or ignoring the problems of other religions and lower castes, their problems become insignificant; by excluding their voices, their silence is ascertained.

When pandemic-related communications are examined through a linguistic lens, we can see the degree to which the Hindu majority's depiction of minority groups as dangerous bodies serves two purposes: to mold and affirm its own ideology and identity, and to amplify and reinforce the deep social divisions and fault lines that have been present throughout India's history. Misrepresentation of Muslims in India (Kumar Reference Kumar2011) and systemic violence against Muslims and Dalits (Teltumbde Reference Teltumbde2010) are not a new phenomenon in India. The advent and widespread use of cell phones in India made organizing by Dalits and people in extreme poverty somewhat of a reality (Doron & Jeffery Reference Doron and Jeffrey2013). Agitation, gathering, and protesting have taken a new role in the Indian system and the visibility of certain protests has increased; the visibility of migrant workers protests is an example. However, the spread of misinformation and hateful rhetoric against Muslims and Dalits has also increased (Doron & Jeffery Reference Doron and Jeffrey2013). The COVID crisis is a moment in this larger milieu which centers on violence against minorities, the good and bad effects of social media, and the rise of Hindu nationalism.

This article studies the language of India's response to COVID-19 surrounding three major events that occurred in the early months of the pandemic: the janta curfew and lighting of the nine diyas, the consequences of and misinformation about the Tablighi Jamaat incident, and the movement of migrant workers through India following the nationwide lockdown. Through an analysis of media reports, speeches made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, and representations on social media made in response to these three events between March 20, 2020 and May 25, 2020, I explore how forms of linguistic trickery—silence, presuppositions, accommodations, othering, dog whistling, and povertyism—were used to suppress, harm, and marginalize two minority groups: Muslims and migrant workers.

A broad spectrum of sources was examined to capture the breadth of India's response to the pandemic. To study the effects of political speech on minority groups in the wake of the COVID-19 crisis, data was gathered from five televised national addresses and two Mann ki baat ‘conversations from the heart’ radio addresses made in March and April 2020 by Narendra Modi. Social media data was gathered from Facebook posts made by one specific Hindu nationalist group to analyze responses to the Tablighi Jamaat and migrant worker crises. This Facebook group was chosen due to the sheer number of members, and because the volume of posts with negative messaging about Muslims shared through this platform has made it a main source for studying the effects of social media on bigotry and hateful messaging.

This article explores how language employed by India's government, mainstream media, and shared on social media—made in the early days of responding to COVID-19—in order to speak to, describe, or represent Hindus, Muslims, and migrant workers, is being used to reshape Indian identity, affirm difference or belonging, and reinforce historical social hierarchies.

SUBALTERNS AND INJURIOUS SPEECH IN THE TIME OF COVID

Subaltern studies tell us that our understanding of the history of colonialism might be framed by a colonialist lens which obscures the voices of the subaltern. The aim of scholarship produced under the banner of subaltern studies is to give a voice to people, the subalterns, whose voice gets silenced by the colonial powers or by upper class/caste, masculine members of the colonized. The history of colonialism and its relationship to contemporary understanding of events in history is pertinent to subaltern studies (Prakash Reference Prakash1994). Professions associated with lower castes like manual labor and cleaning are usually performed by migrant workers in India, and Muslims, owing to their perpetual minority status, join migrant laborers as the subalterns. Looking at harmful speech in the critical moment of the pandemic when it first arrived and spread in India provides a lens to observe the intricacies of the governing and the governed (Chatterjee Reference Chatterjee2004). The governed, in this case Muslims and migrant workers, are the true subaltern whose voices are absent. However, I hope to provide a lens that allows us to look at the framing of the subaltern and opens routes to find subaltern voices. I show how modes of resistance by the subaltern are ultimately decided by those in power. Prakash writes, ‘Subaltern resistance did not simply oppose power but was also constituted by it’ (1994:1480). By studying language that those who govern use towards those who are governed, we also see the parameters that they set that need to be defended. If a Muslim person in India is called a corona jihadi, they must defend this insult and only this insult. Parameters of resistance are set by those who insult. Butler alludes to this phenomenon and suggests, ‘it may be that what is unanticipated about the injurious speech act is what constitutes its injury, the sense of putting its addressee out of control’ (1997:4, emphasis in original).

Language is an essential weapon in the arsenal of most political figures. It can be manipulated to cause unbelievable damage to life and to the fabric of a society. Scholars of critical discourse analysis have shown how discourse is used to reinforce inequality or pose challenges to established systems of hierarchy (van Dijk Reference van Dijk1997). Fairclough (Reference Fairclough2000:165) says that ‘contemporary life is textually mediated’. He adds, ‘political and governmental processes are substantially linguistic processes’ (2000:167). These processes must be studied for understanding government. Studying political speeches and words that mean monumental change to the life of the citizens of a country is critical to understanding not just how a society works but also who the society deems as the other. Tirrell (Reference Tirrell, Maitra and McGowan2012:177) suggests that while language and speech acts do not cause violence, they are ‘action-engendering’—that is, they license non-linguistic behaviors. Unlike the meaning of certain phrases which lose meaning through over use (e.g. ‘this sucks’), hate speech follows a different trajectory since it is action-engendering. The meaning of terms used in hate speech only solidifies.

In the context of the Rwandan genocide with respect to the use of language, Tirrell makes a distinction between derogatory terms and deeply derogatory terms using five criteria. First, deeply derogatory terms serve an ‘insider-outsider function’ (2012:190) which other insults, like ‘snob’ or ‘jerk’, are not capable of doing. People can stop being snobs or continue to be snobs; membership in their racial, ethnic, or cultural groups does not change. But if someone uses ‘Jew’ as an insult, the person the insult is hurled at cannot stop being a Jew; it is assumed that an outsider hurled the insult. Second, deeply derogatory terms are essentializing to the group and the person. Tirrell says, ‘Essentialism fuels fear, generates hate, and purports to justify differential treatment’ (2012:191). Third, deeply derogatory terms are embedded in the social structures of oppression. Fourth, when deeply derogatory terms are used by someone from the oppressing group towards someone in a subordinate group in front of someone else, this usage has a boomerang effect. For example, if a right-wing Hindu calls an Indian Muslim person a Pakistan sympathizer in front of a liberal person, it tells the liberal person that they also cannot be sympathetic towards Pakistan because that would be unacceptable behavior. Boundaries of behavior are drawn this way. Fifth, deeply derogatory terms are ‘action engendering within a context’ (2012:193). For example, calling an African American male a ‘boy’ implies that they do not have the same rights and abilities as men do, thereby denying them a chance to engage in activities that men can engage in. The critical difference between an insult and a derogatory term is that deeply derogatory terms inflict long-term harm and are action engendering. Discussing how toxic speech only intensifies in time, Tirrell says, ‘Each repetition of an outrageous speech act makes the next one less of a surprise, until such speech becomes common enough to seem “normal”, lowering the standard of acceptability’ (Tirrell Reference Tirrell2017:155).

When repeated over years or decades, the use of derogatory terms and phrases for certain groups becomes normal behavior. As words change to action, the magnitude of action is amplified due to the use of action-engendering terms. Beaver & Stanley (Reference Beaver and Stanley2019:517–18, emphasis in original) note that communication by people in power can also become meaningful, even if the derived meaning was not the intended meaning.

The communicative effects of discourse can do well beyond what the speaker is willing to admit, and even well beyond what the speaker recognizes as the communicative effects of her discourse… Intended effects of communication are not automatically more significant, politically or socially, than unintended effects of communication. We are also concerned with explaining effects of communication that are intended but deliberately masked.

Whether a speaker overtly intends to harm certain communities is not a necessity for their speech to be harmful; their intension comes through only after a deeper analysis of their unintended meaning. In India's response to the pandemic, the language (or, in Modi's case, silence) relating to Muslims and migrant workers had a snowball effect and harmed these communities. My analysis encompasses communication that does not appear harmful on the face of it, but when it is put in the context of history and analyzed with a focus on meaning, the results are different.

The next section situates this analysis within the historical context of the Hindu–Muslim conflict in India, Narendra Modi's election, and the rise of pro-Hindu nationalism.

NARENDRA MODI AND THE RISE OF PRO-HINDU NATIONALISM

Throughout India's long history, communal tensions have simmered between Hindus and Muslims. In 1947, when British colonial rule of a seemingly unified India came to an end, the subcontinent was divided along religious lines into two separate countries: India, with a majority of Hindus, and Pakistan, with a majority of Muslims. As a result of the partition, somewhere between 200,000 and two million people died in communal warfare. Over the years, violence continued with thousands of deaths in the 1990s and 2000s, four wars with Pakistan, and an ongoing crisis in Kashmir, the only Muslim-majority state. In the past, Muslims were either celebrated as symbols of ‘unity in diversity’ or demonized as a community that supports terrorism, violence, and communalism. Once Narendra Modi and the Hindu nationalist BJP came into power, India's treatment of the Muslim minority became much worse.

In 2000, Narendra Modi became the chief minister of Gujarat, a state on the western coast of India in part because of his reputation as sympathizer with Hindu nationalist causes. In 2002, about 3,000 Muslims and 700 Hindus were killed in Gujarat and across the country in one of the worst Hindu–Muslim riots in the history of independent India. The riots drew worldwide condemnation, and Modi was criticized for not taking swift action to prevent the deaths of thousands of Muslims. His response was muted, essentially saying that things got out of hand and that the state government could not do anything about it.

Over the next several years, Modi's increasing popularity in Gujarat was due to a variety of economic and political policies, some of which worked. By 2014, he was elected the fourteenth prime minister of India. Aside from his rising popularity, two other factors contributed to his election victory: a lack of leadership in the central government, and the ‘development’ narrative created by him and his supporters (Jaffrelot Reference Jaffrelot2015:152). The 2014 election came after years of allegations of corruption by the Indian National Congress (INC); Narendra Modi and BJP had emerged as the main opposition to the INC. Their ‘development’ agenda focused on fast GDP growth, clearing corruption in government, supporting schemes that were meant for the betterment of the poor, and supporting large scale infrastructure projects. Modi's rise has also been attributed to a new form of mediated populism where media becomes a powerful agent of negotiations between candidates and electors (Chakravartty & Roy Reference Chakravartty and Roy2014). He was able to capitalize on a model of economic growth that he propagated as Chief Minister of Gujarat which Jaffrelot (Reference Jaffrelot2016) argues is a blend of Hindu nationalism and neoliberal capitalism. Modi's use of social media and his election campaigns, which focus on his and only his ability to bring about change in India, also contributed to his rise (S. Rai Reference Rai2019). This along with BJP economic policy to align with global neoliberal capitalism attributed and continues to influence his popularity (Kaur Reference Kaur2014). In addition to the rhetoric of nation-centered development, Modi and BJP also created a narrative that Pakistan, an imagined and sometimes real enemy since 1947, posed a national security threat for India. Over the next five years, Modi's popularity continued to rise. Narendra Modi and BJP won the 2019 election with a landmark victory: of 900 million eligible people, about 550 million voted; however, BJP's vote share was only 37.46%,Footnote 4 an increase from 2014 when the BJP vote share was 31%.

The scale of Modi's victory in 2019 emboldened the BJP to take significant actions in the first year of government that were clearly anti-Muslim. In August 2019, Modi's government revoked the semi-autonomous status of Kashmir, India's only majority-Muslim state; this special status had been granted to Kashmir at the time of modern India's inception. In December 2019, the government enacted the controversial Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), making it nearly impossible for refugees from neighboring Muslim-majority countries—Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan—to become citizens of India. Soon after, the government proposed a National Register of Citizens (NRC) that led to fears that millions of Indian Muslims would be stripped of their citizenship and disenfranchised. These actions led to widespread protests in India. In December, Muslim women in the Shaheen Bagh neighborhood of New Delhi began a sit-in protest that lasted two months. In February 2020, forty-two people were killed in riots in New Delhi and deepened the sectarian divide. Against this backdrop, the coronavirus hit India hard; the Tablighi Jamaat incident in March presented Hindu nationalists with a new opportunity: to scapegoat Muslims for the spread of the virus. In the weeks that followed, Hindu nationalist voices grew louder as pro-Hindu propaganda and anti-Muslim messaging went viral; Muslim voices became increasingly suppressed. By early April, Modi's approval was sixty-two to sixty-eight percent, higher than any other democratically elected national leader.Footnote 5

In moments throughout India's history, those in power have used discourse as a tool to make the voices of certain groups more prominent, to suppress the voices of other groups that do not fit a desired narrative, and to legitimize political power. When discussing subaltern groups in India and finding their voices, Prakash (Reference Prakash1994) says that in historiographies of peasant insurgency written before the arrival of subaltern studies, peasants were regarded as incapable of consciously engaging in insurgency; their rebellion was seen as a labor-related issue, and not as their voice (or statement) on the operations of a nation. In this way, the Shaheen Bagh sit-in protest can be seen as a moment where Muslim voices are heard only in the context of the partition of India, and not in the context of the Muslim-lived experience in modern New Delhi. In addition to being used to elevate or suppress a group's voice, discourse has also been used by those in control to consolidate and legitimize power. When discussing the state of emergency declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in 1975 and the threat it posed to India's democracy, Prakash states, ‘The state combined coercive measure with the powers of patronage and money, on the one hand, and the appeal of populist slogans and programs, on the other, to make a fresh bid for its legitimacy’ (1994:1476). In a similar vein, it is Modi's search for political legitimacy, as a government head and as a leader of the burgeoning Indian middle class, that propels him to speak only to his desired base while sidelining parts of the population that do not fit his narrative of a unified, Hindu majority India.

When COVID-19 hit India, the nation was already in ferment over recent anti-Muslim actions by the Hindu nationalist government; subsequent protests and deadly riots continued to widen the long-standing Hindu–Muslim divide. The COVID-19 pandemic marked a new critical moment in India's history, presenting a fresh opportunity for those in power to amplify and reinforce Indian identity along religious, caste, and economic lines.

LANGUAGE AND INDIA'S RESPONSE TO COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic presented challenges that most modern humans had not experienced before. As cases began to surge in March 2020, the language of India's chaotic and fearful response served to suppress, demonize, and marginalize minority Muslims and migrant workers; strengthen the influence of the Hindu nationalist voice; amplify long-standing communal tensions; and expose the painful and deadly realities of India's social hierarchy. In the next section, we examine how linguistic trickery, employed in the communications of India's early response to the virus, was used to further the aims of Hindu nationalism and to harm and suppress minorities.

Janta curfew, diyas, candles, and ghantas

On March 19, 2020, Narendra Modi made a twenty-eight-minute, televised national addressFootnote 6 to explain the gravity of the COVID-19 crisis, to comfort the nation, and to ask the people to self-impose a one- day, janta curfew ‘curfew by and for people’ to fight the pandemic. In this speech, Modi compared the seriousness of what the country faces to a world war, but that compared to the coronavirus, World Wars I and II actually had less of an impact because fewer countries were involved. Speaking to all of India, Modi's tone was conciliatory, supportive, unifying, and inclusive: ‘Partners/countrymen, whenever I have asked you for something, you have never let me down. This is the power of your blessings: that we are all moving towards our assigned goals. Our efforts are successful sometimes. Today, I am here to ask something of all of you, all the people of this country. I need some of your weeks. I need some of your time.’ He reminded people of their role in building the nation and preventing the disease. At minute 7.25 Modi states, ‘We as citizens have to remind ourselves that we have to solidify our oath as citizens and will follow central and state directives to fight this worldwide pandemic. We have to take an oath that we will try to protect ourselves from getting infected and protect others from getting infected.’

Modi spoke about essential workers and their roles in the crisis, comparing them to soldiers standing like shields between people and the coronavirus. In India, many essential workers—especially those associated with low-paying jobs such as cleaning, garbage collecting, and the service industry—are lower on the caste hierarchy. Modi did not mention the caste hierarchy, but he did request that people following janta curfew honor these workers by standing by their main gates, windows, or balconies and either clap or beat steel plates, or use small bells for five minutes at 5:00 p.m. on March 24. Many Hindu households have a small ‘temple’ area with deities and objects to offer prayers, such as a small bell called ghanti. Since only Hindu households have ghanti, Modi tried to be inclusive of all Indians by adding that people could also clap or use a spoon and plate to make noise. Modi spoke to economic hardship during this period and asked upper class people to support essential workers and those who help in the household. Modi referred to the citizens of India as ‘saathiyon, mitron, deshvaasiyon, pyare deshvasiyon’ ‘teammates, friends, citizens, my dear citizens’. Inclusive and plural pronouns were also used, but this is true for every national address he has given during the coronavirus crisis. Several videos posted on social media by celebrities suggested that the janta curfew was a success, and by all accounts it was. The next day, Modi abruptly declared a national lockdown; the ensuing chaos and immediate shutdown of India's public transportation system ignited another crisis for India's lower-caste migrant workers. This is discussed more fully later in this section.

Two weeks into the turmoil caused by the national lockdown, Modi's address on April 2 was meant to be a ‘pick me up’. Unlike the March 19 address, this 11.25-minute speech calling for unity contained multiple Hindu religious references and dog whistling to the Hindu community. On the escalating hate speech towards Muslims in the wake of the Tablighi Jamaat incident and the suffering of migrant workers trying to get home during the government-imposed lockdown, he was silent.

In this speech, Modi thanked the people who participated in the janta curfew, and then talked about being led from darkness to light. Being led from darkness to light is a common theme in Hindu philosophy: Tamso maa jyotirgamaya, a Sanskrit phrase derived from Brihadaranyaka Upnishad (700 BCE) and used as a motto by the largest life insurance company in India, translates to ‘Lead me from darkness to light’. Modi metaphorically compares the pandemic to darkness and a different future to light. He goes on to ask citizens to show the power of light by turning off their electricity and lighting nine candles at 9:00 p.m. for nine minutes on April 5. Saul (Reference Saul, Fogal, Harris and Cross2018) speaks of the phenomenon of dog whistling in political speeches when people use a word, term, or reference to mean two things. Scholars have shown that Donald Trump used anti Muslim, anti-immigrant, and misogynistic rhetoric to further his message of division and hatred (Goldstein & Hall Reference Goldstein and Hall2017; McIntosh Reference McIntosh, McIntosh and Mendoza-Denton2020). Additionally, Trump's use of dog whistles and insults complements his message of division by offering baffling levels of incoherence which adds up to his message (Slotta Reference Slotta, McIntosh and Mendoza-Denton2020). Like Modi, Trump also disguises his overtly hateful messages in dog whistling and other forms of linguistic trickery. On the face of it, being led from darkness to light seems to be a harmless, culturally situated message. But if we dig a little deeper, we find that it is actually dog whistling: a message that speaks only to caste Hindu India and that leaves behind other religions and lower Hindu castes.

Aspects of the speech assume that his audiences are Hindu (without explicitly saying so) and serve as examples of dog whistling. One is that Modi delivered the speech in standard Sanskritized Hindi, which is associated with a ‘cleaner’, ‘purer’, and ‘uncorrupted’ version of Hindi language (A. Rai Reference Rai2001; King Reference King2001). Its use is controversial in a nation with more than 1,600 languages, twenty-two of which are recognized in its constitution. While standard Hindi is a commonly spoken language, its use in this particular context is considered a form of dog whistling, given Modi's reputation as an anti-Muslim Hindu sympathizer. In another example, Modi referred to ‘130 crore Indian’ three times, which erases the possibility of consideration of systemic discrimination against some people, for example, Muslims and lower castes in the population.

Modi makes references to specific Hindu religious texts and practices in this speech. To illustrate that social distancing is the best way to fight the disease, Modi refers to the ‘Lakshman rekha’ and ‘Raam baan’ subplots in the story of Lord Raam (the most common version of these sacred stories is found in Ramacharitmanas written by Tulsi Das). Lakshman rekha refers to a line demarcating a rule or ethical boundary one must never cross. Raam baan is the arrow out of Lord Raam's bow and is meant to be a panacea. Modi also refers to Hindu religious practices (‘Maha shakti ka jagran’ evoking power within and through religious practice). Such references are not inclusive of the lives and worldviews of the followers of Islam, Christianity, or other religions. Their exclusion also erases the diverse nature of Indian cities and towns and assumes a Hindu voice for everyone.

While Modi's message was one of unity by including collective pronouns such as hum ‘we’, hamara ‘our’, hamara samaaj ‘our community’, and hamara rashtra ‘our country’, he did nothing to assuage the spreading hatred about Islam or migrant workers. His messages were positive, but his language also ignored sects of society that were not his voting bloc. Studies of silence show that the concealment or not addressing of certain problems in a society is a discourse strategy used by politicians to silence people within communities and ignore the existence of uncomfortable truths (Schröter Reference Schröter2014). Modi's use of dog whistling and silence said several things to his followers: He is a Hindu nationalist sympathizer and prioritizes a Hindu narrative. He does not overtly disengage Islam, but his silence on Muslims and migrant workers told people that the issues of oppression being presented to them are not real and that their leader does not consider them important enough to address. And because he does not directly ask his fervent and militant supporters to incite violence, his own hands are clean.

Modi's silence on major conflicts in India became a weapon in this and other speeches. By talking only in general terms, any references to disharmony or discord are ignored. Indeed, there is an almost criminal denial in Modi's silence on matters concerning Muslims. His followers, as we see below, filled the gaps of Modi's silence with bigotry.

Tablighi Jamaat and Muslims as dangerous bodies

The state government of New Delhi advised against all public gatherings in response to the COVID-19 crisis on March 12, 2020. On March 13, 2020, the Tablighi Jamaat, an Islamic missionary organization, proceeded with a three-day, international gathering of 1,400 members in Nizamuddin, New Delhi. Attendees came from all over India and from many countries. It was later reported that some members of the Jamaat had coronavirus and had carried it to different parts of India when they went home. As the number of positive coronavirus cases and deaths skyrocketed in New Delhi and in many other parts of the country, Hindus blamed the country's Muslim minority and the Jamaat for spreading the virus. The treatment of a Tablighi Jammat cannot be understood outside of the general treatment of Muslims in the Indian media. Muslim issues are often depicted as bad because the issue concerns Muslims, not because the system silences certain criminal acts. For example, violence against Muslim women is depicted as a special case of Muslim men being violent, not as a case of gendered violence that women across the religious spectrum face (Kumar Reference Kumar2011). Subsequent social media posts, media organizations, and several government leaders referred to all Muslims as desh ke dushman: ‘enemies of the nation’, ‘outsiders’, ‘dirty’, and ‘vectors of the disease’. Hashtags like #CoronaJihad and #MuslimMeaningTerrorist were shared with hundreds of millions of people by supporters of Modi and the BJP. One central government official called the Tablighi Jamaat a ‘Talibani crime’. Memes suggested that Muslims had nothing but hatred for their own country and everyone in it. As the coronavirus crisis grew in India and hate messages against Muslims intensified, being Indian and Muslim became more dangerous.Footnote 7 On April 2, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi the lone Muslim minister in the BJP-led central government, called the Jamaat gathering a ‘Talibani crime’Footnote 8 ‘Taliban-like crime’. Calling the Talighi Jamaat gathering a ‘Talibani crime’ is tantamount to comparing members of the Jamaat to the Taliban and asks us to presuppose that spreading coronavirus across India was premediated, preplanned, malicious, and organized.

Muslim members of the Jamaat were depicted as criminals as opposed to people who committed an irresponsible action. Hashtags like #CoronaVirusJihad, #TablighiJamaatVirus, #NizamuddinIdiots, #MuslimMeaningTerrorist, and #BioJihad spread like wildfire. One hashtag, #CoronaJihad, had more than 250,000 interactions. Between March 29 and April 3, the collection reach of hate messages about Muslims was as high as 170 million accounts.Footnote 9 Each of these hashtags is deeply derogatory and fulfills the functions of deeply derogatory terms that Tirrell (Reference Tirrell, Maitra and McGowan2012) discusses. Memes spread on social media during this period of time speak to the intensity of hatred towards Muslims and how they were being blamed for COVID-19. The memes discussed below offer concise examples of how hatred is spread through linguistic trickery.

The three memes presented below are from a Facebook group called ‘100 crore rashtravadi Hinduon ka group (Add hote hi 150 Hinduon ko add karen)’. In English, this means ‘A group of 100 crore (1 billion) nationalist Hindus: Add 150 Hindus as soon as you get added [to the group]’. This group has 1.3 million followers and usually supports Hindu fundamentalist ideas that often teeter on the edge of hate speech. Members post memes, messages, misinformation, fake facts, religious thoughts, images of gods, and sometimes lewd photos and videos. The number of followers of this group is enormous. Seeing memes as part of systems that societies generate to reflect their outrage, disgust, or prejudice has been part of the study of social media outlets (Shifman Reference Shifman2014; Moreno-Almeida Reference Moreno-Almeida2020). Memes are pieces of discourse loaded with subversion or hatred; the three memes below fall in the latter category. As Tirrell (Reference Tirrell, Maitra and McGowan2012) shows, normalizing hatred and disdain for minority groups is a strategy for oppressive governments. The three memes presented below speak to this.

The memeFootnote 10 in Figure 1 above, circulated about the Tablighi Jamaat and its supposed role in spreading COVID-19 in India. In this meme, we see a popular Bollywood actor, Akshay Kumar, wearing sunglasses and shown with a beard style associated with Islam as the Maulana ‘high priest’ of Nizamuddin. In the first panel, the Maulana says, ‘I have a scheme’. In the second panel, he says, ‘to double corona cases in five days’. This meme presupposes that the members of Tablighi Jamaat had a role to play in the spread of coronavirus and that this role was premeditated. It also implies that members of the Jamaat would spread the virus deliberately throughout India because, as Muslims, they do not care for the country and its well-being. Within the context of hatred against Muslims in a country that is now governed by a Hindu fundamentalist, it is not a stretch to suggest that the repeated use of the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ strategy creates conditions that are ripe for actions that follow harmful language (Tirrell Reference Tirrell, Maitra and McGowan2012).

Figure 1. Meme circulated about the Tablight Jamaat and its supposed role in the spread of COVID-19 in India (extracted from Facebook).

Indeed, New Delhi saw terrible rioting in January and February 2020 in which more than seventy Muslims were killed, and Muslim neighborhoods suffered much loss of, and harm to, property. While memes appear to be innocent and comical, they are part of an arsenal for accommodating hatred in speech and then in actions.

The meme in Figure 2 speaks to the subjugation of Muslims in India during the COVID-19 crisis, a misconception about the growth of the Muslim population, and the controversial National Registry of Citizens, which threatens to strip the citizenship of millions of poor, illiterate, undocumented Muslims.

Figure 2. Meme circulated about the demographic lie that Muslims have many more children than Hindus (extracted from Facebook).

We see this meme unraveling in two panels. The top panel has a Twitter post by a Muslim man (I am making the assumption that they are Muslim because of the name, Aftab Inamulla Khan, and that they are male because of the photo attached to the account) that says ‘America has deposited Rupees 90,000 in every man's bank account and Rupees 40,000 in every child's account. They have transferred cash. This is what you call a relief package’. The response from a Hindu man (I assume, given their name, Deepak Kandwal) is below this message and says, ‘America's population is about thirty-five crore, India's is more than 135 crore… Here [in India] people with two children pay taxes honestly and people with ten children enjoy subsidies. They won't show papers, but they want a relief package’. Like many governments across the world, the Indian government announced several economic and social relief packages during the COVID-19 crisis. Khan's tweet, comparing India's relief packages to the ones given in the United States, misses several critical points including the difference in the value of money between the two countries, the fact that the United States is the richest country in the world, and that children do not have bank accounts. Be that as it may, the tweet is harmless. In the response, Kandwal takes Khan's tweet and adds bigotry to it by othering Muslim communities and through dog whistling. The meme does not overtly use the ‘they’ pronoun for highlighting an ‘us’ versus ‘them’ dichotomy. Instead, it uses established tropes: Muslims have more children and do not have proper identification to be Indian citizens. In doing so, the meme nods to Hindu fundamentalists and creates more spaces for hatred and bigotry. Statements about Muslims having more children or not being ‘real’ Indian citizens (as reflected in a lack of documentation to be able to prove so) are accommodated (Tirrell Reference Tirrell, Maitra and McGowan2012). These statements are part of the established ways in which Hindu–Muslim violence has been propagated.

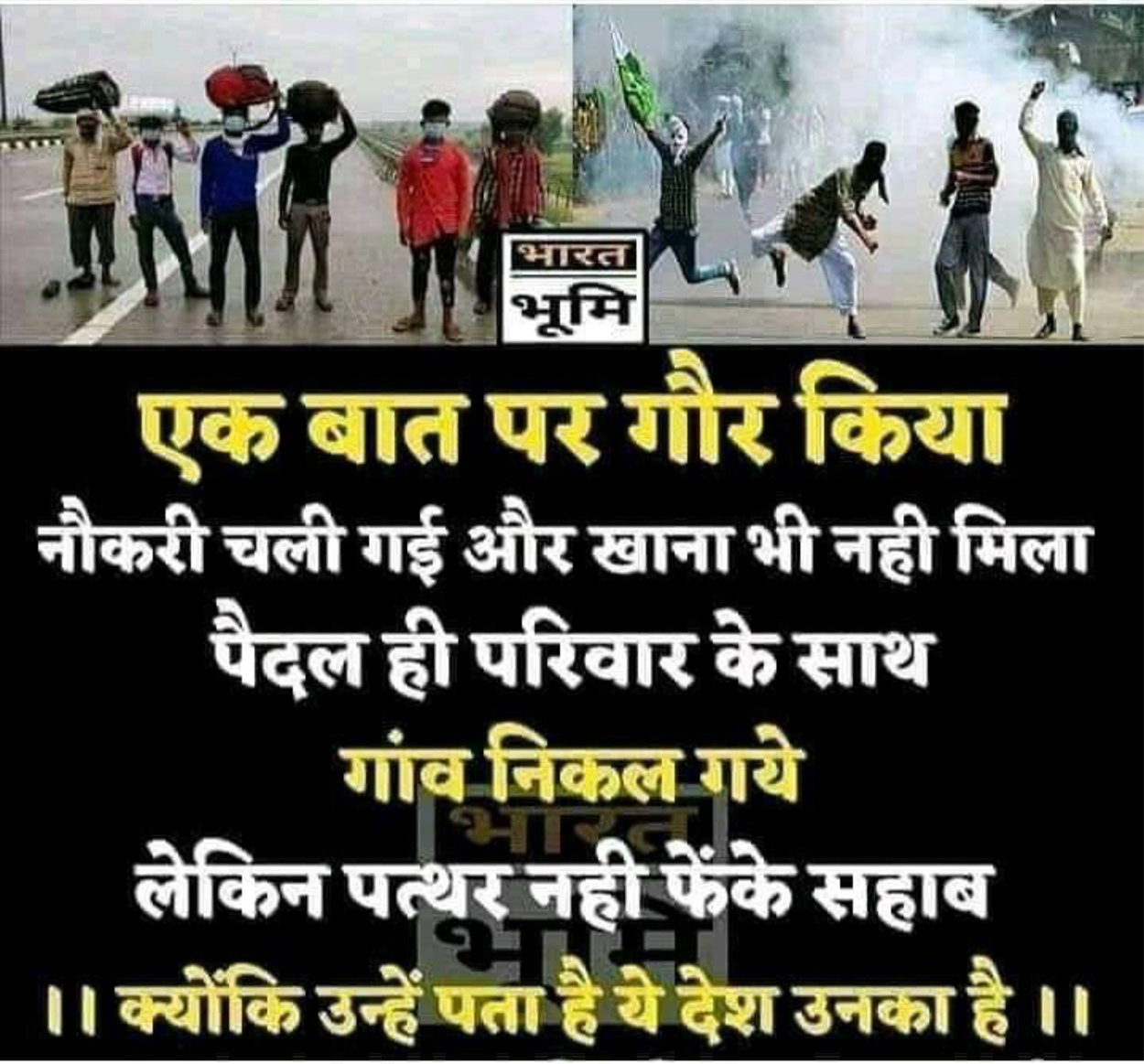

The meme in Figure 3 reads: ‘Have you noticed they [migrant workers represented on the left] lost their jobs, did not have food, and started their journeys to their villages on foot but they never threw rocks [Muslims represented as throwing rocks on the right] because they [migrant workers assumed to be all Hindus] knew that this country belongs to them’. There are several issues with this statement aside from the obvious hatred and bigotry. The statement creates double-layered othering: we have a ‘they’ that is referring to migrant workers and a ‘they’ referring to Muslims. Migrant workers are presented as a poor ‘they’. In this usage, the pronominal implies part of ‘us’ that is poor and deserves kindness and acceptance. The other ‘they’, referring to Muslims and recognizing that Muslims as a group have also been oppressed, implies that Muslims do not consider India to be their country. This othering trope, used only for Muslims in India, has existed at least since the partition of the subcontinent into India and Pakistan in 1947. Throwing stones at police and military is an established way of showing protest in India and has been used throughout history by people from all religious groups. The action is not associated with a specific religion or community, but the meme makes it so.

Figure 3. Meme circulated about the supposed difference in loyalty to India among Hindu migrant workers and Indian Muslims (extracted from Facebook).

The memes above assume that anyone reading them is in on the joke: Muslims do not consider India to be their country; Muslims are dishonest in paying taxes; Muslims have more children than Hindus; members of Tablighi Jamaat planned to spread coronavirus; and that Hindus are generally more honest. The fact that the assumption was meant to be made by people speaks to accommodation: the phenomenon that ensures blunting of reactions to verbal or physical offences. If we continually hear negative statements about a community, a person, a sexuality, a gender, or a religion or religious group, we become used to the bigotry, or worse, we accept it. Further, all three memes use presuppositions as a tool to spread hatred. Presuppositions are not necessarily truth, but presuppositions have acceptability (Langton & West Reference Langton and West1999:309).

Something introduced as a presupposition is harder to challenge since it is meant to be taken for granted. In social media, fiction works within the backdrop of fact. Muslims are oppressed in many ways in India, and memes speak to that truth. There is some truth to fictional representations as far as their power to underline social hierarchies is concerned.

Linguistic trickery employed in the language of political speeches and memes in India's early response to the COVID-19 pandemic served to define who was and who was not a citizen and reinforced social divides along religious and caste lines. Uncomfortable truths about India's social hierarchy were exposed as the response to the crisis illuminated and amplified long- standing Hindu–Muslim tensions and bigotry. India's indifference towards the suffering of another minority group affected by the response to the pandemic—migrant workers—exposed more grim and painful realities about its social hierarchy.

Migrant workers, their journeys, and poverty as sources for dangerous bodies

In the first weeks of India's lockdown, images of millions of migrant workers, with children in their arms and walking hundreds of miles trying to get home, came to define the coronavirus- induced migrant crisis. Many perished in the attempt due to extreme heat and lack of food and water. COVID-19 forced India to acknowledge migrants and exposed its treatment of them.

Migrants are unskilled laborers who travel from one place to another looking for work. They work on large construction projects, in mills as seasonal workers, as domestic help, and as rickshaw pullers; income is low and uneven. Migrant workers frequently lack a permanent address and are homeless; as such, government aid or benefits from government projects cannot reach them. They are everywhere and yet invisible; no one even knows how many there are. In a nation of 1.3 billion, one estimate indicated there may be approximately 100 million migrant laborers in India.Footnote 11 A majority are landless people from rural areas in poorer states such as Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh. Prior to COVID-19, the movement of migrant workers was constant and unnoticed. But because of the Modi government's thoughtless actions relating to the lockdown, the invisible millions suddenly became visible as their extreme suffering was put on full display. Like the Muslim population in India, which is often considered dispensable by the Hindu right, the migrant worker crisis exposed the dispensability of the lower castes whose labor is easily replaced. The violence of the upper and ruling castes was laid bare.

When Modi abruptly announced that the entire country would be on complete lockdown within four hours on March 24, chaos and panic ensued as people tried frantically to get home. India's massive public transportation was shut down, and migrant workers were stuck in place. Many were without food or shelter. The government asked all migrant workers to stay put while arrangements were made, but these attempts fell far below the mark. When the lockdown was extended on April 9, migrant workers gathered outside the Bandra railway station in Mumbai and demanded to go home. As more time went by, migrant workers began protesting and states arranged to bring workers home. At one point, the Maharashtra state home minister said that the state was allowing migrant workers to walk back home since no other arrangements were in place. For thousands of migrant workers, this meant walking hundreds of miles on foot with no money or provisions. Aside from being inhumane, the idea that migrant workers could walk home was impractical. Throughout April and May, several state governments went back and forth with the central government on how to get migrant workers back to their home states and individual homes. Soon, the despair, poverty, and hunger were on display as migrant workers protested, and India was confronted with images of migrant faces, bodies, and their desperate walks on interstate highways—many died in the heat from lack of water and food. There were images on the BBC which showed migrants sleeping under a bridge next to sewage and garbage bags.Footnote 12 The April death of a twelve-year-old migrant worker who had walked several kilometers and died just twenty kilometers from her home spurred debate and outrage.Footnote 13 Images of a child trying to breastfeed while its mother lay dead went viralFootnote 14 in May and sparked more outrage.

India is a developing country, and while extreme poverty is often on display in metropolitan areas, it is not commonly on this scale. The migrant worker crisis led to several protests where participants were criticized for the lack of social distancing during the protests and the poverty of migrant workers. Images from media outlets showed hordes of people standing too close together and waiting for buses or protesting at train stations. Soon, the crowds became a vector of the disease and a recipient of pity. Every news piece on the migrant crisis highlighted the plight of the migrants, but not the callousness the Modi government showed towards its poorest and most marginalized citizens. Migrant workers did not become dangerous bodies in the same way that Muslims did. They became pitiable bodies, and when they protested, gathered, and demanded to go home, they became dangerous, as the meme in Figure 3 shows. And yet, their othering was not as absolute as that of Muslims. The meme speaks to this point because it assumes that most migrant workers are poor Hindus. Migrants are marginalized not because they are poor, not because they are Hindu; this assumption leaves them out of the narrative of ‘the enemy within’ that Hindu nationalists associate with Indian Muslims.

As migrant workers became visible to the established social hierarchy, they were put into their own category and defined by their poverty and helplessness. The narrative of povertyism and othering of people in poverty has been argued by Krumer-Nevo & Benjamin (Reference Krumer-Nevo and Benjamin2010), who propose counter-narratives to the way poverty is usually represented. By doing so, Krumer-Nevo & Benjamin challenge the hegemonic narrative of representing poverty by creating counter-narratives that rely on showing poverty as a consequence of policy and history, not a condition of being poor. The counter-narratives proposed by Krumer-Nevo & Benjamin include: (i) the voice-action counter-narrative, which highlights the voices and knowledge structures of people in poverty; (ii) the agency/resistance counter-narrative, which shows how people in poverty negotiate structures created to keep people in poverty; and (iii) the structure/context counter-narrative, which shows how people in poverty are not inferior and that structures influence poverty. These counter-narratives focus on front lining voices of communities that are othered. Othering on the basis of poverty creates a narrative of helplessness and assumes that people in poverty rely on governments and citizens to care for them. In fact, Munger (Reference Munger2002) suggests that even repeated use of the word ‘poor’ is stigmatizing. The process of othering people in poverty, in which a superior ‘us’ and an inferior ‘them’ are delineated, is reflected in policy and visible in language. As such, othering becomes a vehicle for discrimination and a rationale for it (Holden Reference Holden1997). The categorization of people in poverty as the other leads to their voices becoming unheard in policy and in media (Krumer-Nevo Reference Krumer-Nevo2002; Lister Reference Lister2008; McKendrick, Sinclair, Irwin, O'Donnell, Scott, & Dobbie Reference McKendrick, Sinclair, Irwin, O'Donnell, Scott and Dobbie2008). In the early weeks of the COVID-19 crisis, othering of migrant workers was manifested clearly in government directives, schemes, and media representations.

People in poverty are often categorized in a way that interacts with other forms of systemic inequalities. An example of this phenomenon is the use of the term ‘inner city’ in the United States. Since overtly derogatory terms like the n-word are not acceptable, using terms like ‘welfare’ and ‘inner city’ communicate an association with and bias towards African Americans without explicitly saying so (Stanley Reference Stanley2015). Repeated association between words and social meaning leads to these associations becoming part of conventional meaning. When certain associations (e.g. Blacks and welfare) are repeatedly made, we assume they are true and take no issue with them. Lack of respect for a group results in lack of empathy, which makes the groups rife for propaganda. When certain associations and words become part of everyday use, ‘there will be expressions that have normal contents, which express these contents via ways that erodes empathy for a group’ (Stanley Reference Stanley2015:139). Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, migrant workers were not recognized in the social hierarchy. But as migrant workers became visible as a group, linguistic tricks—repeated associations, othering, and silence—served to create and define their identity as a separate, impoverished segment in the margins of society that should be pitied and continually helped.

In a radio addressFootnote 15 on March 29, Modi sought forgiveness and sacrifice from the people of India—especially poor people—and suggested that the actions he and the government were taking were necessary to win against coronavirus. Modi accepted some responsibility but did not offer any help to migrant workers who would soon be desperate, hungry, and dying. Eventually, special trains ran to take migrant workers home, but only after much outrage from migrant workers and opposition parties, and after much back and forth between the central government and state governments about who would pay for the trains and provisions. The shocking images of men, women, and children migrant workers suffering ‘in your face’ poverty (in a country whose recent narrative had been ‘development’, no less) also played a role. The trains were called the Shramik Express. Shramik is a Hindi word means ‘someone who makes a living through hard work ‘shram’’. The word shram refers to any kind of work and is not limited to physical work or labor; however, the use of this word in association with migrant workers does suggest a designation of physical labor. The categorization and othering brought about through the association of migrant workers with the Shramik Express also further exacerbated povertyism: discrimination on the basis of poverty. The crisis exposed the creation of a migrant worker category as a subject of the state: they became a category of poor people that needed something from the state, which had become an agent of giving. When the state becomes the agent of providing and communicates this point, the receivers become the other: Voiceless and without agency.

Analysis of more than forty news reports about migrant workers suggests that their representation is steeped in othering and excludes their voice. In one example, Anil Deshmukh, the home minister of the state of Maharashtra,Footnote 16 reportedly made the following statement in English: ‘The Telangana [state] government dropped them at the Maharashtra border. Our government provided them shelter and food and later dropped them at the Madhya Pradesh [state] border. The Maharashtra government did not charge anything for it’. In this statement, migrant workers are referred to as though they were inanimate objects to be moved from point A to point B. The exclusion of migrant voices, coupled with images of their desperation and destitution, provided fertile grounds to create a complete lack of agency for migrant workers. In television interviews, migrant workers were asked about the conditions they were living in and not about solutions. Suggesting solutions is the work of people in power, and migrant workers were certainly not that.

Media coverage of the migrant workers crisis used several terms and phrases that warrant attention. ‘Stranded’ was used to describe the fact that migrant workers had no way to reach their homes. In fact, they were not ‘stranded’ as much as imprisoned and unable to get anywhere. The phrase ‘ferry migrant workers’ suggested migrant workers’ sense of an absolute lack of agency. Reports assumed that migrant workers did not have voices and needed the help that the government was providing instead of pointing to the government's creation of the crisis.

Remarks that were offensive were also reproduced in media coverage over and over again. Statements such as ‘migrant workers were instructed to wear masks and maintain social distancing’, ‘migrant workers were given food packages’, ‘migrant workers were stamped with indelible ink’, ‘migrant workers were violating lockdown norms’, and the most problematic, ‘migrant workers were gathering in large crowds’ made in English indicated that migrant workers were unable to decide what was right for their own safety. Statements such as ‘instructed to wear masks and maintain social distancing’, ‘given food packets’, and ‘stamped with indelible ink’ also presupposed a lack of understanding of the gravity of the pandemic on the part of migrant workers. Phrases such as these told people that migrant workers were part of a new social category that was not ‘us’. They were different, in need to help, and unable to make decisions about their own health and safety. Their poverty was to be seen a trait, not as a temporary condition worsened by government inaction. They were to be pitied.

Linguistic trickery—repeated associations, othering, and silence—employed in media coverage, government communications, and schemes, worked to create a new category for migrant workers in the social hierarchy. To be a migrant worker is to be associated with an impoverished segment of society that should be pitied and helped, not treated as equal, not treated as an ignored part of the general population but treated as one that would continually need assistance, and not empowered to make their own choices, but sidelined and always needing constant government help and care.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this article, I have argued that when society faces a moment of crisis, its language can reflect, expose, and reinforce societal chaos and fault lines. For India, the COVID-19 pandemic was one such moment. As India came to terms with the disease, the coronavirus’ impacts on different populations exposed and widened India's deep social, economic, and religious divides. Voices of the truly disempowered are hard to hear and subaltern studies aims to find these voices. As the example of Muslims and migrant workers during the COVID crisis in India shows, subaltern voices are filtered through various mediums. In colonial India, the colonist translated these voices; in modern India, social media translates them.

Forms of linguistic trickery—silence, presuppositions, accommodations, othering, dog whistling, and povertyism—were used in the response to the pandemic to suppress, harm, and marginalize two minority groups: Muslims and migrant workers. Harmful linguistic practices in the early weeks of the pandemic served to strengthen the influence of the majority Hindu nationalist voice while silencing other voices; to define Indian identity along religious lines and amplify the majority's hatred of Muslims; and to characterize and marginalize migrant workers, thereby exposing the painful and deadly realities of India's social hierarchy. This article demonstrates how a society's language is used by those in power to reflect, shape, and reinforce meaning, social hierarchies, and marginalization in a time of crisis.

In February 2021, life was almost back to normal in Aligarh. Reports from family and friends suggest that markets were full again, weddings and gatherings were back, vaccination drives were in full force and COVID cases were non-existent. People had forgotten COVID, Muslims, and migrant workers. Everything changed in the course of a few weeks and April 2021 saw the worst surge of COVID cases in India. My parents who spent fall 2020 in California were back in India in January 2021. They were living close to normal lives when the second wave of COVID hit India. In April 2021, they had not left their home in weeks. My father tells me how every time he opens WhatsApp, he reads messages about people who have died due to COVID. His best friend's wife died on May 3, 2021. Two other family members passed in the first week of May. Many extended family members are sick or recovering. The number of COVID cases and COVID related deaths are severely underreported. The healthcare system has completely collapsed. Narendra Modi is silent. State governments are silent, and people are dying.