Introduction

As obligate scavengers at the top of the trophic web and K-selected species, vultures can be particularly affected by either direct or indirect anthropogenic mortality, both at a local level and worldwide (Lambertucci Reference Lambertucci2010, Margalida Reference Margalida2012, Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Keesing and Virani2012, Pain et al. Reference Pain, Bowden, Cunningham, Cuthbert, Das, Gilbert and Jakati2008).

Direct persecution, whereby vultures are victims of deliberate illegal killing driven by dislike or superstition (Botha et al. Reference Botha, Andevski, Bowden, Gudka, Safford, Tavares and Williams2017), is not the main driver of global vulture decline but can become locally frequent and have a large impact on several species (Brochet et al. Reference Brochet, Jbour, Sheldon, Porter, Jones, Al Fazari and Al Saghier2019, Cailly Arnulphi et al. Reference Cailly Arnulphi, Lambertucci and Borghi2017, Daboné et al. Reference Daboné, Ouéda, Thompson, Adjakpa and Weesie2023, Oppel et al. Reference Oppel, Arkumarev, Bakari, Dobrev, Saravia-Mullin, Adefolu and Sözüer2021). Indirect anthropogenic mortality also represents a major threat to vultures (Arrondo et al. Reference Arrondo, Sanz-Aguilar, Pérez-García, Cortés-Avizanda, Sánchez-Zapata and Donázar2020, Berny et al. Reference Berny, Vilagines, Cugnasse, Mastain, Chollet, Joncour and Razin2015). For instance, secondary poisoning by veterinary pharmaceuticals administered to livestock, especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as flunixin, nimesulide, and carprofen, is implicated in the global collapse of many vulture species (Botha et al. Reference Botha, Andevski, Bowden, Gudka, Safford, Tavares and Williams2017). In Asia, three formerly widespread species suffered a severe, rapid decline due to the use of diclofenac (Green et al. Reference Green, Newton, Shultz, Cunningham, Gilbert, Pain and Prakash2004), and recent simulations suggested its high potential impact even on Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus populations in Europe (Green et al. Reference Green, Donazar, Sánchez‐Zapata and Margalida2016). Other major causes of decline are represented by the use of pesticides in poison baits, targeted at killing wild mammalian predators and feral dogs (Diekmann and Strachan Reference Diekmann and Strachan2006), and by lead poisoning, through the consumption of spent ammunition fragments in game carcasses and gut piles (Bassi et al. Reference Bassi, Facoetti, Ferloni, Pastorino, Bianchi, Fedrizzi and Bertoletti2021, Monclús et al. Reference Monclús, Shore and Krone2020, Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Wiemeyer and Lambertucci2020b). Finally, impact with wind turbines and death by collisions with power lines or electrocution represents another significant life threat for large soaring birds and raptors (de Lucas et al. Reference de Lucas, Ferrer, Bechard and Muñoz2012, Martin et al. Reference Martin, Portugal and Murn2012, Sarrazin et al. Reference Sarrazin, Bagnolini, Pinna, Danchin and Clobert1994).

Although the Griffon Vulture occurs in several European countries, few studies have investigated extensively its death causes or mortality rates in Europe so far (Arrondo et al. Reference Arrondo, Sanz-Aguilar, Pérez-García, Cortés-Avizanda, Sánchez-Zapata and Donázar2020, Berny et al. Reference Berny, Vilagines, Cugnasse, Mastain, Chollet, Joncour and Razin2015, Cano Reference Cano2016, Xirouchakis Reference Xirouchakis, Chancellor and Meyburg2004). In particular, no published information is reported for Italy, where five Griffon Vulture populations exist, mainly originating from resource-demanding conservation translocations (Genero Reference Genero2009). This species, however, is still considered “Near Threatened” at the national level (Gustin et al. Reference Gustin, Nardelli, Brichetti, Battistoni, Rondinini and Teofili2021), both because of the low number of breeding pairs and the persistence of high (though unquantified) rates of anthropogenic mortality (Brambilla et al. Reference Brambilla, Gustin and Celada2011, Genero Reference Genero2009, Gustin et al. Reference Gustin, Brambilla and Celada2009).

To support management actions and conservation efforts, we collected and analysed records on reported Griffon Vulture mortality in the central Apennines from 1994 to 2020. Specifically, we aimed at investigating patterns of mortality according to year and month. Moreover, we explored the association between mortality, gender, and age class. Finally, we investigated the prevalence of the causes of death as well as the temporal trend of mortality causes. Resulting information should help in planning and enforcing appropriate conservation measures, thus aiding in preventing or decreasing further losses from non-natural causes, and prioritising management actions.

Methods

Study area

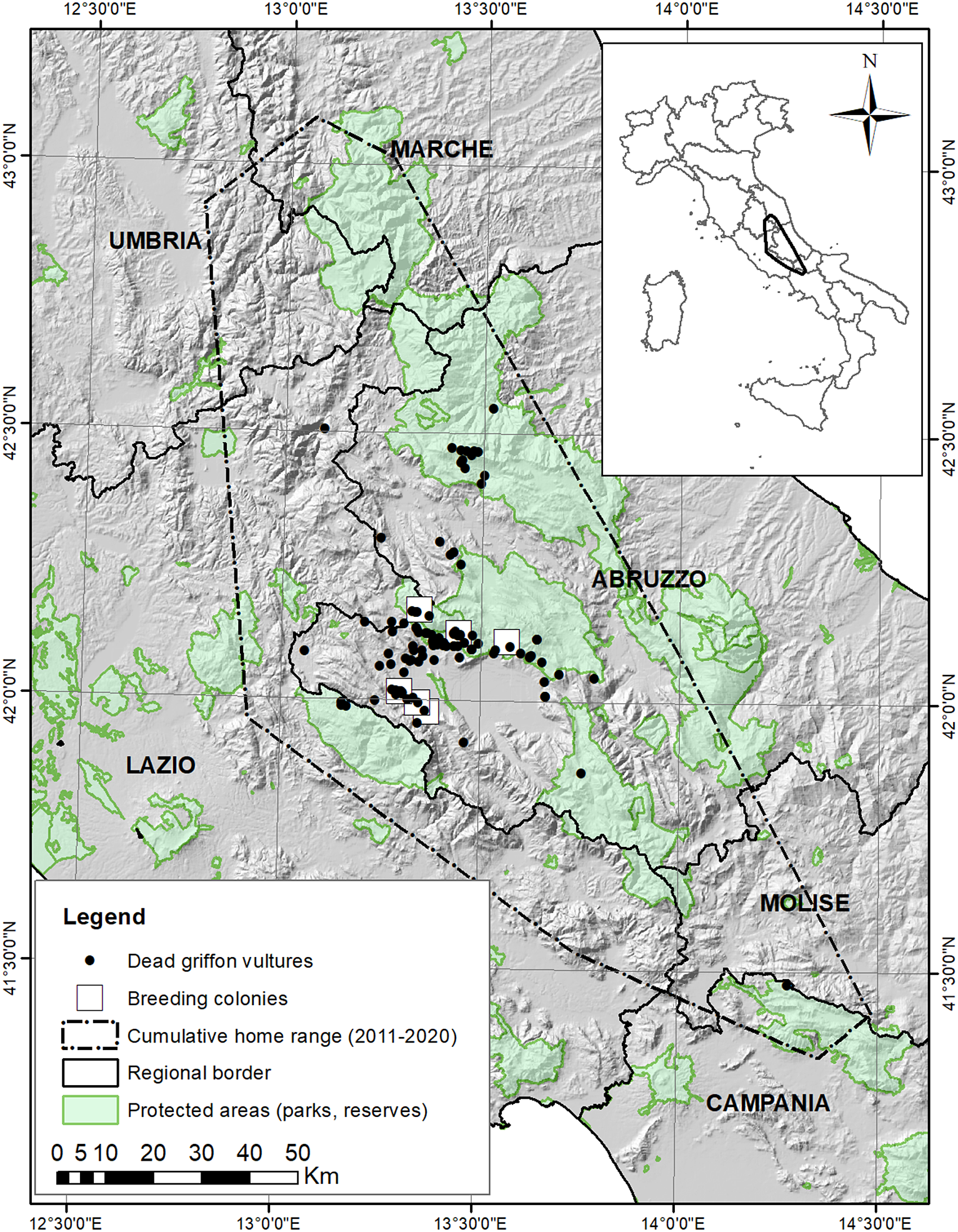

The study area, mainly located in L’Aquila province, Abruzzo region, is in the central Apennines (42°10’N 13°20’E), a mountainous zone, with ridges oriented from north-west to south-east, and elevations exceeding 2,000 m a.s.l. (maximum elevation 2,914 m in the Gran Sasso Massif) (Figure 1). Climate is predominantly Mediterranean-montane, with cold snowy winters and drier, warm summers (Piovesan et al. Reference Piovesan, Bernabei, Di Filippo, Romagnoli and Schirone2003). Livestock breeding is common: goats, sheep, cattle, and equids (in decreasing order of abundance), with a total of >95,500 heads per year in the whole L’Aquila province (Banca Dati Nazionale dell’Anagrafe Zootecnica 2022). Equids and cattle are usually left unattended in pastures. In some areas, livestock roam freely in winter, although at lower elevations. Sheep, goats, and cattle are usually kept on farms during winter. Transhumance, which represents a seasonally important source of food for vultures (Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Oliva-Vidal, Llamas and Colomer2018), is still widely practised in the area, with thousands of livestock heads spread across pastures from mid-June to early October.

Figure 1. Distribution of dead Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus (N = 123) in the central Apennines from 1994 to 2020, with respect to protected areas. The cumulative home range (minimum convex polygon drawn around all telemetry fixes) of GPS-instrumented resident vultures (2010–2020 data) is also shown.

Study species

Griffon Vulture is a large colonial vulture of the Accipitridae family (weight 6–11 kg, wingspan 2.3–2.8 m). It is distributed from the Iberian peninsula and northern Morocco to the western Himalayan range, also occurring through the south-western Arabian peninsula, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Sudan (Campbell Reference Campbell2015). Its life expectancy could be up to 41 years in captivity (Carey and Judge Reference Carey and Judge2000), and the onset of senescence has been estimated at 28 years in the wild (Chantepie et al. Reference Chantepie, Teplitsky, Pavard, Sarrazin, Descaves, Lecuyer and Robert2016). Sexual maturity is attained at four years (Møller Reference Møller2006) and the monogamous pairs lay one egg per breeding season (Cramp and Simmons Reference Cramp and Simmons1980).

The last evidence of Griffon Vulture breeding in the central Apennines dates back to the mid-sixteenth century (Pandolfi and Zanazzo Reference Pandolfi and Zanazzo1994). The current population in the study area originated from 93 individuals donated by the Spanish Government to the Italian Ministry of Agriculture-Forest Service. Birds were released from 1994 to 2002 mainly in the Monte Velino Reserve (MVR) (Potena et al. Reference Potena, Panella, Sammarone, Altea, Spinetti, Opramolla and Posillico2009). Currently, six breeding sites occur around the Fucino plain (Figure 1). The average ± SD reproductive success and number of fledglings per year from 2003 to 2015 were 0.77 ± 0.21 and 21.5 ± 5.9, respectively, and the breeding population is increasing (Altea et al. Reference Altea, Panella, Opramolla and Posillico2016).

Data sources

Overall, 148 occurrences of dead (N = 123, range: 0–27 individuals per year) (Figure 2) and impaired birds (N = 25) were recorded from July 1994 to December 2020. Sixty (48.8%) dead and 14 rescued vultures were marked birds, two of which were rescued twice. Records about mortality or rescues of impaired vultures were compiled from the archives of MVR, the office responsible for monitoring Griffon Vultures in the area. Dead and impaired vultures were mainly discovered by local people during outdoor activities, hikers, Forest Service, and subsequently Carabinieri, provincial police, and park wardens. Eight vultures were found thanks to satellite telemetry. Records covered information about the date, location, age class, whether the bird was GPS-tagged or otherwise marked, photographs, maps, description of the remains, and their perceived preservation status; in addition, death records also contained information on the causes of death from the associated necropsy report. As it was not always possible to collect all these data for every dead/rescued vulture, the sample size changed in different statistical analyses.

Figure 2. Annual reported number of dead Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus from 1995 to 2020 in the central Apennines. Different colours represent different mortality causes. The yellow line represents the number of breeding pairs in each year.

Annual trend of mortality

Based on the approximate date of death estimated during necropsy or on the detection date, we were able to assign 120 out of 123 mortality events to a given year. The first mortality event was documented soon after the first five vultures were released (mid-July 1994), while the last known death occurred in November 2020. Since mortality data for 1994 were limited to six months (July–December), we analysed inter-annual variation in mortality only from 1995 onwards. We also investigated the variation in occurrence of mortality events at within-year periods, considering only those records where necropsy or evidence allowed estimation of time of death to a given month (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of dead Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus from the central Apennines (1994–2020), according to gender and age class by month and breeding phenology.

Age class and sex

The age class of vultures (juveniles, subadults, and adults) was assigned according to standard phenotypic characteristics, including moult patterns (Duriez et al. Reference Duriez, Eliotout and Sarrazin2011, Zuberogoitia et al. Reference Zuberogoitia, De La Puente, Elorriaga, Alonso, Palomares and Martínez2013). Age classification was made by experienced and trained personnel while handling birds. We were never able to retrieve dead nestlings, though we were aware that some mortality occurred. Age class distribution of the vulture population was drawn from 303 different individuals live-captured 631 times (some individuals were captured more than once) during 30 capture sessions from 2010 to 2020.

The sex of dead vultures was determined starting from 2010 onwards from both a morphological examination of the gonads during necropsy or from DNA analyses. Molecular sexing of dead and live-captured individuals from 2010 to 2011 was run from tissue samples using P2/P8 primers (Griffiths et al. Reference Griffiths, Double, Orr and Dawson1998). Conversely, from 2011 to 2020, the individuals were sexed from plucked feathers following Garofalo et al. (Reference Garofalo, Fanelli, Opramolla, Polidori, Tancredi, Altea and Posillico2016).

Mortality causes

Post-mortem necropsy and toxicological analyses of 95 carcasses were carried out at the Istituto Zooprofilattico Sperimentale (Experimental Zooprophylactic Institute – IZS) per l’Abruzzo e il Molise (IZSAM, Teramo and Avezzano laboratories), while four carcasses were examined at IZS Lazio e Toscana (IZSLT), two at the Forensic Laboratory of the Veterinary Faculty, University of Teramo (VFTU), one at the Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga National Park (PNGSL), and another one at the IZS del Mezzogiorno (IZSDMP, Portici laboratory). In 20 cases (16%), carcasses consisted of too few remains and were not delivered for necropsy.

The causes of death were defined as “undetermined” if the necropsy was not conclusive, and “not-determinable” when paucity of the remains did not allow further analyses. When the report mentioned the occurrence of more than one likely cause of death, we questioned the pathologist for further clarification and identification of the ultimate cause. All vultures whose cause of death was related to human activities or infrastructures were further classified as died from direct (poisoning, shooting, and an instance where a vulture was likely beaten to death) or indirect (collision with wind turbines, suspended wires, vertical structures, and electrocution) anthropogenic causes, as opposite to natural causes (disease). For three vultures from two sites (distance 3.5 km) recovered within eight days, no toxic substances were detected from carcass samples. Nevertheless, we considered them as poisoned based on evidence from carcass status (Fajardo and Zorrilla Reference Fajardo and Zorrilla2016), and because a bait containing a carbamate insecticide (methomyl) was found a few days after the vultures, 1 km away from one of the birds. Harmed birds that died soon after their retrieval for the same reason causing their impairment (N = 5) were included in the sample of dead vultures.

Reporting of toxicological analyses by IZSAM has been standardised in its current array since 2000. Accordingly, to quantify the prevalence of detected toxic substances, we selected only toxicological reports of vultures which underwent post-mortem from 2000 onwards yielding positive results (N = 48). Depending upon preservation status, vultures were tested against diseases subject to mandatory sanitary surveillance (i.e. avian influenza, West Nile disease, Usutu virus, and Newcastle disease). Diagnoses of pathologies were carried out depending on the outcome of the necropsy inspection. From 2011 to 2017 a subsample of vultures (N = 11), three of which were also tested for embedded shots by X-ray, was analysed for lead concentration according to Bassi et al. (Reference Bassi, Facoetti, Ferloni, Pastorino, Bianchi, Fedrizzi and Bertoletti2021). The occurrence of NSAIDs was assessed from 2017 to 2020 for 13 vultures. The presence of toxic substances commonly employed to poison wildlife and domestic animals was assayed (Table S1). The occurrence of further single toxics was tested for by pathologist’s examination of remains thanks to evidence from specific inquiries. Due to the paucity of analysable matter, some panels were not fully implemented.

Statistical methods

We aimed at modelling temporal variation in mortality, expressed as the proportion of individuals found dead, but the number of individuals in the population in each year was unknown. We, therefore, used the number of breeding pairs in each year (Altea et al. Reference Altea, Panella, Opramolla and Posillico2016, MVR unpublished data) as a proxy for population size (Van Beest et al. Reference Van Beest, Van Den Bremer, De Boer, Heitkönig and Monteiro2008), and modelled the annual number of casualties in a generalised linear model (GLM) model assuming a negative binomial distribution of the data where the log-number of breeding pairs was entered as an offset (see Supplementary material 2 for further details on this model).

To test for within-year variations in mortality, we used harmonic analysis (periodic regression), whereby we transformed months into angles (January = 30°; December = 360°) and then included the sines and cosines of these angles, and their interaction, into a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) model as predictors. With this formulation, the sines contrast spring vs. autumn mortality, while cosines contrast summer vs. winter mortality. The GLMM model assumed a negative binomial distribution of the data and included the year as a random grouping factor and the sine of the month (transformed as above) as a random slope within year (see Supplementary material 3 for a mathematical description of the model and code). The diagnostic of the model indicated that the model did not show zero-inflation nor overdispersion (details not shown).

We used a multinomial logit model for modelling the relative proportion of adults, subadults, and juveniles found dead in each year, while logistic regressions were used to investigate annual variation in the sex ratio of individuals found dead.

Given the small sample size, only descriptive statistics are shown for impaired vultures. The analyses were performed in R 3.2.2 (R Core Team 2016) with the glmmTMB (Magnusson et al. Reference Magnusson, Skaug, Nielsen, Berg, Kristensen, Maechler and van Bentham2017) and VGAM libraries (Yee et al. Reference Yee, Stoklosa and Huggins2015).

Results

Annual trends of mortality

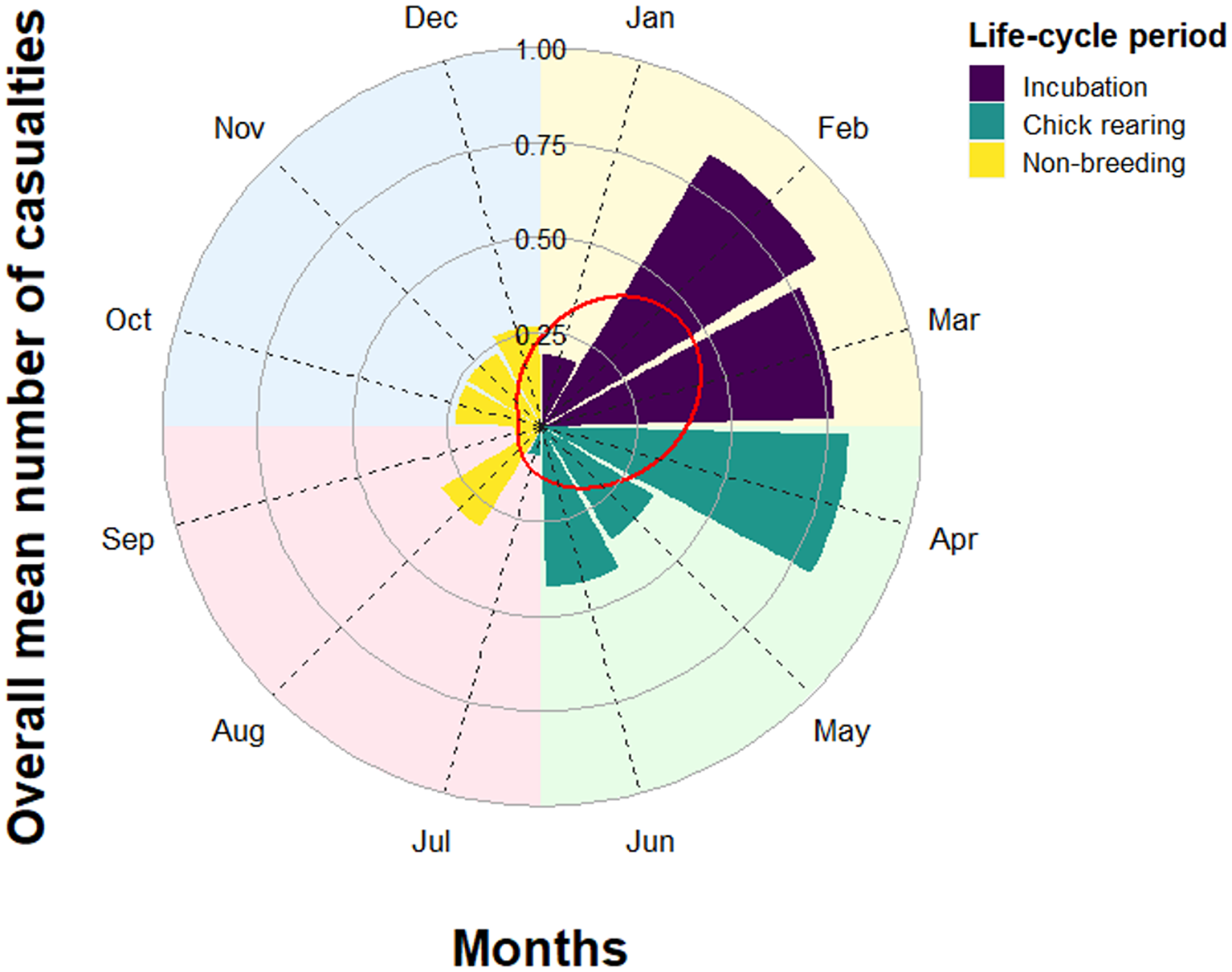

The average (mean ± SE) annual mortality was 4.69 ± 1.14 vultures per year. We found no significant temporal trend in reported annual mortality during the 26 years of study (model coefficient ± SE: -0.03 ± 0.03, z 21 = 0.96, P = 0.34). Harmonic analysis showed that the number of reported mortality events peaked in March (day 73 = 14 March), whereas the minimum was in October (day 289 = 16 October) (Table 2). Out of the 120 mortality events classified according to season, 76.7% occurred in winter (N = 48) and spring (N = 44), while 75.8% occurred during the incubation (January–March, N = 48) and chick-rearing periods (April–July, N = 43) (Figure 3).

Table 2. Result of the negative binomial generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) fitting a harmonic regression model to the yearly variation in Griffon Vulture Gyps fulvus mortality. Year was included as a random grouping factor and the sine of month as a random slope within year. According to the harmonic analysis, sine, and cosine contrasted spring vs. autumn and summer vs. winter, respectively. Variances of the random effects were 0.83 for year and 1.25 for sine of the month within year. SE = standard error.

Figure 3. Mean overall number of dead Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus per month (N = 120). Different periods of the annual life cycle are highlighted. Background colours represent the four seasons. The red line represents the fitted values of the harmonic regression model.

Age class and sex effects

Mortality in different age classes could be determined for 106 out of 123 dead vultures (86%) (Table 1). The frequency of occurrence of age classes of dead vultures in 2010–2020 did not differ from that observed in individuals captured during the same period (G = 0.78, df = 2, P = 0.68). The multinomial logit model showed that on average, juveniles (N = 9) were found dead less often than adults (N = 49) (coef: -1.70 ± 0.37, z = 4.61, P <0.001), while adults and subadults (N = 48) were found in similar proportions on average (z = -0.13, P = 0.90) (Table 1). In addition, the proportion of dead subadults and juveniles did not decrease over the years compared with adults (z ≥-1.43, P ≥0.14).

Sex could be assessed for 68 dead vultures (54.8% of the total sample), out of which 40 were males and 28 females (1.43:1), which did not differ significantly from 1:1 (exact binomial text, P = 0.18) (Table 1). A binomial regression model showed that the sex ratio of dead vultures did not vary through the years (z = -0.35, P = 0.73).

Mortality causes

A post-mortem and a toxicological screening were carried out on 103 (83.7%) dead vultures. Poisoning was by far the most important mortality factor, affecting 55 Griffon Vultures and representing 53.4% of all mortality events and 73.3% of all cases for which mortality causes could be determined (N = 75). Natural mortality occurred in only four vultures that died from diseases, all the remaining events represented direct (N = 57, 55.3%) or indirect (N = 15, 14.6%) anthropogenic mortality. Shooting occurred just once, while electrocution (N = 6, 5.8%) and collision with wind turbines (N = 9, 8.7%) represented the most important causes of deaths due to human infrastructures. For 19 (18.4%) birds, the cause of death was unknown.

From 2000 to 2020, 92 vultures were sent for necropsy. The preservation status of carcasses allowed for toxicological analyses in 84 cases. Toxicological tests were carried out screening 49 substances overall, though not all were tested for in all cases. On average 17.3 toxic agents (± 12.6 SD, range: 4–36) were tested for each vulture. Most vultures (92%) were tested for carbamates, while 54% and 52% were tested for organochlorines and organophosphates, respectively. Plant-derived toxins (mostly strychnine, and coumarin in three cases) were investigated in 44% of birds, while inorganic compounds (i.e. zinc phosphide and arsenic) were tested in 23% of cases. Rodenticides (8%) and molluscicides (metaldehyde, 2% of vultures) were the least tested substances (Table S1); 48 vultures were positive at such tests. Overall, 14 toxic substances (29% of the total tested) were detected. One to six substances were identified in each poisoned bird (mean ± SD = 1.44 ± 0.99). Carbamates recurred most frequently, as they were detected 35 times in 34 poisoned vultures, followed by organochlorine pesticides and strychnine, detected 27 and 4 times in 12 and 4 birds, respectively (Table 3).

Table 3. Toxic substances detected from 48 Griffon Vultures Gyps fulvus poisoned from 2000 to 2020 in the central Apennines. Occurrence (%) of toxic agents is reported with respect to total poisoned vultures (N = 48, sum >100%) and to the total occurrences of toxic substances (N = 69, sum =100%) in dead vultures. Up to six substances were detected in a single bird.

In 2020, a Griffon Vulture that died of carbofuran poisoning resulted positive for diclofenac (7% of 13 birds tested for NSAIDs). However, its concentration was by far lower than the one known to be lethal (L. Giannetti–IZSLT, pers. comm.).

None of the Griffon Vultures screened by X-ray yielded embedded or ingested lead shots (E. Bassi, pers. comm.). Two birds (18%) showed subclinical to clinical lead concentration (E. Bassi, pers. comm.). In these latter cases, mortality may have occurred due to the level of lead concentration in the bones.

Discussion

Annual and seasonal trends of mortality

We did not detect an annual change in the number of dead vultures. As our sample was mostly made from reported casualties, annual random variation in search effort could have biased our results. However, a fair number of vultures have been reported by hikers, farmers, and hunters, from which we assume their regular presence in the study area. Moreover, local Forest Service station officers and park wardens regularly patrol assigned areas. Hence, we are confident that this bias was negligible. In addition, by using the breeding population size as a proxy for the total population, we statistically controlled for the potential bias due to a positive association between the occurrence of mortality events and the increase in Griffon Vulture population size over the years (Altea et al. Reference Altea, Panella, Opramolla and Posillico2016).

A decline in the annual breeding success and population growth, and an increase in mortality of young age classes have been reported in Spain for the Griffon Vulture as a consequence of a severe food shortage related to the implementation of sanitary legislation after the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) outbreak in 2009 (Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Margalida, Carrete and Sánchez-Zapata2009, Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Colomer and Sanuy2011, Zuberogoitia et al. Reference Zuberogoitia, Martínez, Margalida, Gómez, Azkona and Martínez2010). In our area, we did not observe an annual increase in detected mortality after 2009, nor a decrease in the breeding population (Altea et al. Reference Altea, Panella, Opramolla and Posillico2016). Hence, survival in our population seems not to be related to the availability of food provisioning. However, mortality peaked at the end of winter (in between incubation and the chick-rearing period), while it was at its minimum in mid-autumn (during the non-breeding season). These mortality patterns are similar to those observed in other species such as Cinereous Vulture (Aegypius monachus) in Spain (Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2008), Oriental White-backed Vulture (Gyps bengalensis) in Pakistan (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Virani, Watson, Oaks, Benson, Khan and Ahmed2002), and Andean Condor (Vultur gryphus) in Argentina (Estrada Pacheco et al. Reference Estrada Pacheco, Jacome, Astore, Borghi and Piña2020, but see Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Heredia, Razin and Hernández2008). Both resource distribution and meteorological conditions could explain our results. During winter, food resources occur within a more restricted range than in summer as the abundant transhumant herds are no longer spread across pastures and many resident herds are kept at low elevations. Moreover, meteorological conditions in winter are less favourable for soaring, the typical low energy-demanding flight of large scavenging raptors (Ruxton and Houston Reference Ruxton and Houston2004). In addition, winter rigours combined with high energy investment in reproduction for breeding individuals require a greater energy expenditure, making Griffon Vultures more susceptible to illness and death. Conversely, during the warmer season, although chicks demand a huge food provision, energy expenditure for thermoregulation is lower, and the abundance of livestock is higher because of incoming transhumant herds (Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Oliva-Vidal, Llamas and Colomer2018). Another, non-mutually exclusive explanation of the intra-annual pattern of mortality that we observed could be related to the timing when poisoned baits are used. Horses and cattle are usually left unattended in pastures, even during the season when the young are born, between March and May. This might result in an increase in livestock losses due to predation on calves and foals by wild and domestic predators in late winter/spring (Cozza et al. Reference Cozza, Fico, Battistini and Rogers1996, our study area), and preventive and retaliatory reactions by stakeholders might be the main cause for poisoning (Ntemiri et al. Reference Ntemiri, Saravia, Angelidis, Baxevani, Probonas, Kret and Mertzanis2018). Wolves (Canis lupus) and an undetermined number of feral dogs and wolf–dog hybrids have steadily inhabited the whole Apennines totalling c.2,400 individuals (La Morgia et al. Reference La Morgia, Marucco, Aragno, Salvatori, Gervasi, De Angelis and Fabbri2022). Notwithstanding its protected status, unresolved issues of wolf–livestock conflict generate reactions by local farmers and residents to control wolf numbers through illegal means. Indeed, human-related mortality, including poisoning, is responsible for more than 70% of wolf casualties in the central and northern Apennines (Lovari et al. Reference Lovari, Sforzi, Scala and Fico2007, Musto et al. Reference Musto, Cerri, Galaverni, Caniglia, Fabbri, Apollonio and Mucci2021).

Age class and sex effects

Age class was known for 86% of Griffon Vultures in our sample, however only a significantly smaller portion was represented by juveniles, while subadults and adults appeared in similar proportions, reflecting the age class distribution in our study population. Conversely, Berny et al. (Reference Berny, Vilagines, Cugnasse, Mastain, Chollet, Joncour and Razin2015) found a higher proportion of juveniles in their sample of dead vultures, and the same occurred for Oriental White-backed Vultures in Pakistan (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Virani, Watson, Oaks, Benson, Khan and Ahmed2002). As suggested by Harel et al. (Reference Harel, Horvitz and Nathan2016), juveniles have reduced skills in managing soaring flights compared with experienced vultures, showing lower soaring–gliding efficiency and spending more energy per time unit. Although their lower flying performance could be buffered by social facilitation while foraging (Jackson et al. Reference Jackson, Ruxton and Houston2008), their survival could be affected because they are more prone to traumas due to flight accidents. Moreover, their later arrival at carrion sites predisposes them to suboptimal food intake in terms of both quantity and quality, as observed at feeding stations (Bosè et al. Reference Bosè, Duriez and Sarrazin2012, Bosé and Sarrazin Reference Bosé and Sarrazin2007), which consequently affects survival. In addition, juveniles and immature vultures are more likely to undertake long trips and disperse at several hundred kilometres from their natal range than subadults and adults (Alarcón and Lambertucci Reference Alarcón and Lambertucci2018), and during such forays, many are likely to die. In such cases, well outside the study area, dead juveniles could rarely be retrieved or even reported. Such a circumstance could partly explain why the number of reported dead juveniles was lower in the central Apennines compared with other study sites.

Although both the breeding population of Griffon Vultures and the number of fledged chicks increased over the years (Altea et al. Reference Altea, Panella, Opramolla and Posillico2016), both the proportion of dead juveniles and the overall detected mortality did not. As the survival rate of Griffon Vulture increases with age until adulthood (Chantepie et al. Reference Chantepie, Teplitsky, Pavard, Sarrazin, Descaves, Lecuyer and Robert2016), and the proportion of adults in the population increased progressively after translocations were completed, we could conclude that the growth of the breeding population was not paralleled by an increase in the overall reported mortality. On the other hand, the small number of dead juveniles and their higher dispersal rates could have played a role in obscuring possibly higher juvenile mortality from reported occurrences.

The sex ratio of dead individuals (1.43:1) was not significantly different from the typical 1:1 ratio for Griffon Vultures (Bosé et al. Reference Bosé, Le Gouar, Arthur, Lambourdiere, Choisy, Henriquet and Lecuyer2007). Such a mortality pattern was similar to that found for Andean Condors (Estrada Pacheco et al. Reference Estrada Pacheco, Jacome, Astore, Borghi and Piña2020), Oriental White-backed Vultures in Punjab, Pakistan (Gilbert et al. Reference Gilbert, Virani, Watson, Oaks, Benson, Khan and Ahmed2002), Bearded Vultures in Europe (Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Heredia, Razin and Hernández2008), and Griffon Vultures in France (Berny et al. Reference Berny, Vilagines, Cugnasse, Mastain, Chollet, Joncour and Razin2015). This is not surprising as the monogamous Griffon Vulture is sexually monomorphic (Bosé et al. Reference Bosé, Le Gouar, Arthur, Lambourdiere, Choisy, Henriquet and Lecuyer2007), and both sexes equally invest in nesting and parental care (Cramp and Simmons Reference Cramp and Simmons1982). However, despite what was previously reported (Altea et al. Reference Altea, Panella, De Sanctis, Morini, Opramolla, Bartolo, Pascazi, Mezzavilla and Scarton2013, Monsarrat et al. Reference Monsarrat, Benhamou, Sarrazin, Bessa-Gomes, Bouten and Duriez2013), Morant et al. (Reference Morant, Arrondo, Sánchez‐Zapata, Donázar, Cortés‐Avizanda, De La Riva and Blanco2023) recently found significant differences in movement patterns of breeding Griffon Vultures in different populations in Spain. There, females showed larger home ranges and lower monthly fidelity than males (Morant et al. Reference Morant, Arrondo, Sánchez‐Zapata, Donázar, Cortés‐Avizanda, De La Riva and Blanco2023).

Mortality causes

Worldwide, poisoning represents the most frequent threat for vultures (Botha et al. Reference Botha, Andevski, Bowden, Gudka, Safford, Tavares and Williams2017, Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Martínez-López and Lambertucci2019b). Secondary and unintentional poisoning has been recognised as the most recurrent vulture intoxication type in Europe (Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2008). The central Apennines population is no exception, as poisoning incidents accounted for 83.7% of mortality cases where the cause was identified. Poisoning events could affect high numbers of vultures (so-called massive poisoning), and repeated massive poisoning incidents could lead to local extinction (Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Shaw, Beyers, Buij, Murn, Thiollay and Beale2016). In our study area, two massive poisoning events were reported, in 1998 and 2007. In addition, even if not directly lethal, poisoning could impair flight ability, which could predispose vultures to deadly accidents like, for instance, collision with suspended wires or wind blades and electrocution (Mineau et al. Reference Mineau, Fletcher, Glaser, Thomas, Brassard, Wilson and Elliott1999).

In our study, carbamates were by far the most recurrent toxic component determining the death of reported vultures. Other pesticides (organochlorines) and strychnine were detected as well, though less frequently. Moreover, rodenticides were found in only 8% of tested birds, a low prevalence that is comparable with that found in the population of Griffon Vultures in the Pyrenees (Oliva-Vidal et al. Reference Oliva-Vidal, Martínez, Sánchez-Barbudo, Camarero, Colomer, Margalida and Mateo2022b). The prevalence of carbamates (among which carbofuran and aldicarb dominated, although both have been banned since 2007–2008) is a recurrent trait in both scavengers and wildlife poisoning issues and these substances have been found to affect several species in different geographical areas (Estrada Pacheco et al. Reference Estrada Pacheco, Jacome, Astore, Borghi and Piña2020, Guitart et al. Reference Guitart, Sachana, Caloni, Croubels, Vandenbroucke and Berny2010, Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2009, Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Martínez-López and Lambertucci2019b, Safford et al. Reference Safford, Andevski, Botha, Bowden, Crockford, Garbett and Margalida2019). The prevalence of specific toxic substances in wildlife poisoning is usually linked to factors like lethality, cost, and availability of stocks before their prohibition (Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Blanco, Madariaga, Boeri, Teijeiro, Bianco and Lambertucci2019a), and less dependent upon the legal status of such substances, as underscored by the abundant and recurrent use of carbamates in western Europe, most of which have been banned as pesticides for more than 15 years (Poledník et al. Reference Poledník, Poledníková, Větrovcová, Hlaváč, Jansman, van Tulden, Pichler and Richards2011). Although strychnine has been banned in Italy since the 1970s, its use in baits might have been sustained by illegal trade from abroad. Similarly, the illegal trade of carbofuran and aldicarb could also represent, in the long term, a continuous source of such pesticides, which could be halted only by a global ban (López-Bao and Mateo-Tomás Reference López-Bao and Mateo-Tomás2022). In our opinion, most of the poisoning episodes in our study represent secondary or indirect poisoning events (see also Oliva-Vidal et al. Reference Oliva-Vidal, Hernández-Matías, García, Colomer, Real and Margalida2022a), as suggested, in some cases, by the association of dead dogs, wolves, foxes, and corvids with vulture casualties, as well as Canidae remains found within the gizzard or gastrointestinal content of vultures. Evidence of accidental contamination has never been found by personnel in charge of the investigation, nor do landfills or garbage dumps occur where vultures could have been contaminated. Despite our small sample of NSAID- and lead-tested vultures being restricted in time, our effort allowed the reporting of the first-ever diclofenac-intoxicated Griffon Vulture in Italy, and the second intoxicated vulture in Europe, after the death of a juvenile Cinereous Vulture in Spain (Herrero-Villar et al. Reference Herrero-Villar, Delepoulle, Suárez-Regalado, Solano-Manrique, Juan-Sallés, Iglesias-Lebrija and Camarero2021). In one case, clinical lead concentration was reported in the bones, which could have caused or contributed to death. The recorded prevalence of diclofenac and lead at subclinical to clinical levels in a small sample of vultures, although hampering robust conclusions on their impact at a population level, suggests the need for a continued and integrated effort to monitor the occurrence of those substances (Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Bogliani, Bowden, Donázar, Genero, Gilbert and Karesh2014), not to overlook their influence on Griffon Vulture conservation.

Management and conservation implications

Addressing the gaps and uncertainties in the existing information on mortality events of Griffon Vultures could assist in developing protocols to handle them efficiently. Our findings showed that most deaths in the central Apennines are due to anthropogenic causes, similar to what happens for other vultures in Europe and worldwide (Berny et al. Reference Berny, Vilagines, Cugnasse, Mastain, Chollet, Joncour and Razin2015, Botha et al. Reference Botha, Andevski, Bowden, Gudka, Safford, Tavares and Williams2017, Green et al. Reference Green, Donazar, Sánchez‐Zapata and Margalida2016, Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2008, López-Bao and Mateo-Tomás Reference López-Bao and Mateo-Tomás2022, Margalida Reference Margalida2012, Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Shaw, Beyers, Buij, Murn, Thiollay and Beale2016, Smits and Naidoo Reference Smits, Naidoo, Sarasola, Grande and Negro2018). However, the main cause of death may vary with geographical area and target species (e.g. Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Keesing and Virani2012), and thorough post-mortem protocols are necessary to reduce the number of cases where necropsy fails to identify the cause of death (38% in our study). Considering the prevalence of mortality causes in our small sample of GPS-tagged birds, the proportion of deaths from unknown reasons falls to 12.5%, although non-natural (i.e. human-related) mortality still accounts for most (62.5%) of the casualties. Consequently, a huge effort is necessary to monitor a larger number of individuals with GPS tags, allowing an unbiased estimation of mortality rates (Arrondo et al. Reference Arrondo, Sanz-Aguilar, Pérez-García, Cortés-Avizanda, Sánchez-Zapata and Donázar2020, Monti et al. Reference Monti, Serroni, Rotondaro, Sangiuliano, Sforzi, Opramolla and Pascazi2022), faster retrieval of carcasses (Peshev et al. Reference Peshev, Mitrevichin, Stoyanov, Grozdanov and Stoynov2022), and, possibly, the prosecution of those responsible. Procedures to investigate the proximate and ultimate causes of death would imply formal coordination and common objectives among (1) public veterinary bureaux in charge of carrying out post-mortem investigations, (2) agencies responsible for wildlife management and conservation, and (3) public bodies with responsibility for carrying out investigations and crime prosecutions (Poledník et al. Reference Poledník, Poledníková, Větrovcová, Hlaváč, Jansman, van Tulden, Pichler and Richards2011). We also recommend a uniform and enhanced panel of toxic substances to be analysed, always including lead, as well as screening for the occurrence of potential new threats after veterinary use of NSAIDs (Herrero-Villar et al. Reference Herrero-Villar, Velarde, Camarero, Taggart, Bandeira, Fonseca and Marco2020). Thus, the occurrence of NSAIDs should be routinely monitored in all potentially affected raptor species during management programmes or for those individuals entering wildlife recovery centres, as well as in livestock carcasses, both freely available for scavengers and provisioned in feeding stations. This would provide information to foster management actions, along with awareness-raising campaigns aimed at preventing the inappropriate use of such veterinary drugs (Moreno-Opo et al. Reference Moreno-Opo, Carapeto, Casimiro, Rubio, Muñoz, Moreno and Aymerich2021), and eventually leading to a ban on diclofenac use in livestock (Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Green, Hiraldo, Blanco, Sánchez-Zapata, Santangeli and Duriez2021). Notwithstanding that Griffon Vultures in Abruzzo mostly feed on livestock carrion (>90%, MP pers. obs.), lead poisoning from spent ammunition deserves a thorough monitoring complemented by an extensive survey of embedded shots through X-ray given its potential impact on wildlife populations.

Intended conservation strategies should also emphasise human–wildlife conflicts, mostly on livestock losses from wild and domestic predators, i.e. wolves and dogs (Mateo‐Tomás et al. Reference Mateo‐Tomás, Olea, Sánchez‐Barbudo and Mateo2012, Sánchez-Barbudo et al. Reference Sánchez-Barbudo, Camarero and Mateo2012) or, more recently, on the presumed predatory behaviour of Griffon Vultures attacking livestock (Lambertucci et al. Reference Lambertucci, Margalida, Speziale, Amar, Ballejo, Bildstein and Blanco2021, Oliva-Vidal et al. Reference Oliva-Vidal, Hernández-Matías, García, Colomer, Real and Margalida2022a), both deserving sound mitigation measures. Existing technical opportunities for wildlife crime prosecution should be readily implemented, and also by enforcing further anti-poison dog units (Poledník et al. Reference Poledník, Poledníková, Větrovcová, Hlaváč, Jansman, van Tulden, Pichler and Richards2011) prioritising poisoning hot spots. Other anthropogenic threats should also be addressed, namely the impact of wind farms and electrocution. Although only 6.5% of reported casualties were determined by accidents that occurred at wind farms, attention should be paid to possible underestimation of such a threat (Carrete et al. Reference Carrete, Sánchez-Zapata, Benítez, Lobón and Donázar2009), as well as to the application of mitigation and compensation measures to prevent, decrease, and compensate such mortality (Cole and Dahl Reference Cole and Dahl2013, de Lucas et al. Reference de Lucas, Ferrer, Bechard and Muñoz2012, Tomé et al. Reference Tomé, Canário, Leitão, Pires, Repas and Köppel2017). Similarly, we advocate urgently addressing electrocution by the identification and prioritisation of areas at higher risk and subsequently securing relevant structures (Eccleston and Harness Reference Eccleston, Harness, Sarasola, Grande and Negro2018, Tintó et al. Reference Tintó, Real and Mañosa2010).

The provision of food to Griffon Vultures for conservation purposes, though not fully justified in the central Apennines, could reasonably alleviate food shortage during critical periods of the year when mortality is higher (e.g. winter, breeding), likely increasing survival. Although buffering low natural-food availability could be beneficial, providing an objective support to food supplementation should be mandatory, as there are implications and drawbacks linked to food subsidies which should not be overlooked (Cortés‐Avizanda et al. Reference Cortés‐Avizanda, Blanco, DeVault, Markandya, Virani, Brandt and Donázar2016, Moreno-Opo et al. Reference Moreno-Opo, Trujillano, Arredondo, González and Margalida2015). Re-implementing food supplementation in the Apennines could exert some benefits if guided by a sound, biologically based strategy, taking advantage of local opportunities and following examples such as the farm-based feeding stations in Sardinia (Aresu et al. Reference Aresu, Rotta, Fozzi, Campus, Muzzeddu, Secci and Fozzi2021).

Currently, more than 70% of vulture species worldwide are prone to extinction by human activities (Buechley and Şekercioğlu Reference Buechley and Şekercioğlu2016, IUCN 2019), because their feeding behaviour exposes them to contaminants and pathogens (Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Blanco and Lambertucci2020a), often in large numbers because of their gregarious foraging behaviour (Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Keesing and Virani2012). In addition, vultures are long-lived species that occupy the highest trophic levels and are therefore predisposed to bioaccumulation (Smits and Naidoo Reference Smits, Naidoo, Sarasola, Grande and Negro2018). For these reasons, deliberate or incidental poisoning (Ragothaman and Chirukandoth Reference Ragothaman, Chirukandoth and Richards2011) represent the most widespread reasons for the decline of obligate scavengers worldwide (Plaza et al. Reference Plaza, Blanco, Madariaga, Boeri, Teijeiro, Bianco and Lambertucci2019a,b). As reported by Monti et al. (Reference Monti, Serroni, Rotondaro, Sangiuliano, Sforzi, Opramolla and Pascazi2022) for 20 Griffon Vultures monitored by GPS tracking in the central and southern Apennines, poisoning affected 40% of dead vultures, and thus reasonably exerts quite an impact on vulture survival in our study area. We hope that the overwhelming occurrence of poisoning through time reported in this study and its high potential impact on survival (Monti et al. Reference Monti, Serroni, Rotondaro, Sangiuliano, Sforzi, Opramolla and Pascazi2022) could represent a starting point for a widespread and common conservation strategy not only for vultures, but also for other protected and threatened wildlife in Mediterranean countries such as, for instance, the wolf, Brown Bear (Ursus arctos), and Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), whose ranges largely overlap those of vultures in the study area.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270923000199.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the many persons facilitating our collection of records, especially those from Corpo Forestale dello Stato/Carabinieri Forestali from Comando Regionale Abruzzo, Comando Provinciale/Gruppo L’Aquila, Reparto Carabinieri Biodiversità Pescara, the many Comando Stazione Forestale, and colleagues from Riserva Naturale Orientata Monte Velino. Parco Nazionale Gran Sasso Laga, Parco Regionale Sirente-Velino, Riserva Regionale Montagne della Duchessa, and Parco Regionale dei Monti Simbruini, also contributed data. Experimental Zooprophylactic Institutes of Abruzzo and Molise, Lazio and Toscana, del Mezzogiorno Portici, Veterinary Faculty of Teramo and the Veterinary Services of Avezzano (Sandro Bisciardi and Vera De Angelis), Sulmona (Marco Amicarella), L’Aquila (Massimo Ciuffetelli and Livio Giammaria), and Rieti (Fernando Salvi and Mauro Grillo), as well as the Centro Recupero Animali Selvatici-Rome, provided invaluable support. Francesca Manzia, Pietro Badagliacca, Stefania Salucci, Daria Di Sabatino, Francesco Tancredi, and Nicola D’Alessio shared information on procedures for necropsies and toxicological screening. Enrico Bassi allowed the results of lead analysis to be quoted. Antoni Margalida, Paolo Ciucci, and anonymous referees made valuable comments enhancing the manuscript. AC was partially financially supported by grant FSE-REACT EU, DM 10/08/2021 n. 1062.