No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

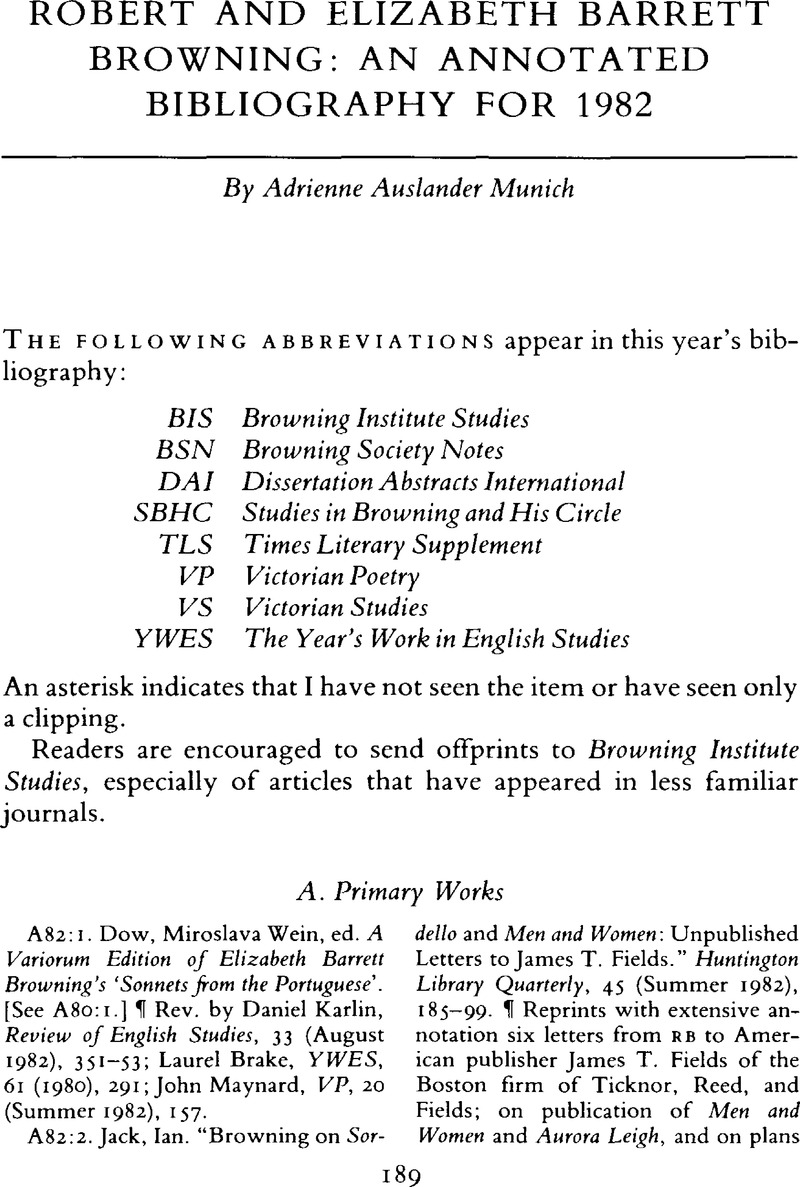

Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Annotated Bibliography for 1982

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2008

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Browning Bibliography

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1984

References

A. Primary Works

A82:1.Dow, Miroslava Wein, ed. A Variorum Edition of Elizabeth Barrett Browning's ‘Sonnets from the Portuguese’. [See A80:1.] ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

A82:2.Jack, Ian. “Browning on Sordello and Men and Women: Unpublished Letters to James T. Fields.” Huntington Library Quarterly, 45 (Summer 1982), 185–18. ¶ Reprints with extensive annotation six letters from RB to American publisher James T. Fields of the Boston firm of Ticknor, Reed, and Fields; on publication of Men and Women and Aurora Leigh, and on plans to revise Sordello.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

A82:3.King, Roma A. Jr., ed. The Complete Works of Robert Browning, Vol. 5. [See A81:3.] ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

A82:5.Pettigrew, John, and Collins, Thomas J., eds. Robert Browning: The Poems. [See A81:5]Google Scholar

B. Reference and Bibliographical Works and Exhibitions

B82:1.Freeman, Ronald E. “A Checklist of Publications [July 1981-December 1981].” SBHC, 10 (Spring 1982), 69–72.Google Scholar

B82:2.Kelley, Philip, and Hudson, Ronald. “The Brownings' Correspondence: Supplement to the Checklist.” BIS, 10 (1982), 163–68.Google Scholar

B82:3.Munich, Adrienne. “Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning: An Annotated Bibliography for 1980.” BIS, 10 (1982), 169–80.Google Scholar

B82:4.Tobias, Richard C. “Brownings” in “Victorian Bibliography for 1981.” VS, 25 (Summer 1982), 578–57.Google Scholar

C. Biography, Criticism, and Miscellaneous

C82:1. “Barrett Browning/Mitford Letters Published.” Through Casa Guidi Windows: The Bulletin of the Browning Institute, No. 6 (Winter 1982/1983), p. 7. ¶ Mary Russell Mitford's correspondence with her friend EBB, more than 500 letters, covers the most interesting period of Ebb'S life from her serious illness to the publication of Aurora Leigh.Google Scholar

C82:2.Berens, Michael John. “‘Startle Thee By Strangeness’: The Affective Strategy of the Maker-See in the Poetry of Robert Browning.” DAI, 43 (1982), 1149A (University of California, Los Angeles), Rb employed manipulations of speech to convey moral judgments and to “startle the reader to respond to a character with the truth within himself” (p. 1149).Google Scholar

C82:3.Berridge, Elizabeth. “A Visit to Florence.” BSN, 12 (04 1982), 13–19. ¶ Report of a visit to Florence by the London Browning Society.Google Scholar

C82:4.Elizabeth, Bieman. “Triads and Trinity in the Poetry of Robert Browning,” in Neoplatonism and Christian Thought, ed. O'Meara, Dominic J.. (International Society for Neoplatonic Studies.) Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982. pp. 187–202. ¶ Reprint of C80:5.Google Scholar

C82:5.Bloom, Harold, and Munich, Adrienne, eds. Robert Browning: A Collection of Critical Essays. [See C79:6.]Google Scholar

C82:6.Borowitz, Albert. “The Ring and the Book and the Murder.” A Gallery of Sinister Perspectives: Ten Crimes and a Scandal. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1982. pp. 1–10. ¶ Contrasts the legal judgments with those of the Roman citizens and primarily with the wider philosophical and social judgments of Pope and poet to conclude that a criminal case is not “the exclusive preserve of its parties, witnesses, lawyers, and judges, that it may have philosophic or social significance” (p. 9).Google Scholar

C82:7. “Browning/Bronson Letters to Be Published.” The Armstrong Browning Newsletter, No. 27 (Winter 1982), p. 4. ¶ Michael Meredith will edit letters from Browning family and Katharine Bronson.Google Scholar

C82:8. “Browning Societies Report.” Through Casa Guidi Windows: The Bulletin of the Browning Institute, No. 6 (Winter 1982/1983), p. 4. ¶ News from four Browning Societies.Google Scholar

C82:9.Brugière, Bernard. L'Univers Imaginaire de Robert Browning. [See C79:12.] ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

C82:10.Cheskin, Arnold. “Robert Browning's Climactic Hebraic Connections with Emma Lazarus and Emily Harris.” SBHC, 10 (Fall 1982), 9–22. ¶ Rb'S interest in Hebraic materials in the 1880s was enriched by his association with two Jewish women: Emma Lazarus and Emily Harris. Ferishtah's Fancies shows some effects of his friendship with Lazarus, while Emily Harris deepened the poet's understanding of traditional Judaism.Google Scholar

C82:11.Cooper, Helen Margaret. “Elizabeth Barrett Browning: A Theory of Women's Poetry.” DAI, 43 (1982), 1149A (Rutgers). ¶ A “consideration of the dialectic between the male poetic and the female cultural traditions” to which Ebb was heir provides a model for a theory of the woman poet's growth into her mature voice.Google Scholar

C82:12.Crowder, Ashby Bland. “‘Porphyria's Lover’: A Reason for Action.” South Central Bulletin, 37 (Winter 1977), 145–46. ¶ Perhaps Porphyria's lover is not a lunatic but coolly and rationally kills the woman he loves because he hates her for being dominating and deceptive.Google Scholar

C82:13.Crowder, Ashby Bland. “Robert Browning and His Publisher.” SBHC, 10 (Fall 1982), 49–52. ¶ Rb'S new and pleasant association with George Murray Smith, publisher of The Ring and the Book.Google Scholar

C82:14.Dahl, Curtis. “Learning and Loving: Browning's ‘Development’ and the Victorian Debate Over Education.” SBHC, 10 (Fall 1982), 23–24. ¶ “‘Development’ encapsulates a tremendous amount of the contemporary literary discussion of education and also expresses a theological position central to his [RB'S] liberal Christian faith” (p. 23).Google Scholar

C82:15.Davie, Donald. Dissentient Voice. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1982. ix + 154 pp. ¶ “Robert Browning,” (pp. 32–47). “[G]reat poet though Browning is, he is none the less evidence – indeed, because of his great talents he is singularly compelling evidence – of how by the middle of the nineteenth century Dissent had become a vector of unen-lightenment” (p. 34). With extensive citations from Santayana andGoogle Scholar

Christmas-Eve and Easter-Day. “Two of Browning's Heirs” (pp. 48–64). Jack Clemo and Rudyard Kipling: “none of Browning's heirs in poetry, precisely because they were Browning's heirs, have been able to put together that homogeneous worldview, at once ‘cultured’ and Christian, which Browning's mother may have inhabited in the London suburb of Camberwell about 1820” (p. 63).Google Scholar

C82:16.Davies, Cory Bieman. “‘Another Pattern’: T. S. Eliot's Shifting Relationship to Robert Browning.” SBHC, 10 (Fall 1982), 35–48. ¶ While Eliot grudgingly accorded respect to RB, he was greatly influenced by RB'S dramatic form, an influence he gradually acknowledged.Google Scholar

C82:17.Doane, Margaret. “‘Thy Soul is in Thy Face’: Physical Appearance and Character in Browning's Poems.” SBHC, 10 (Spring 1982), 36–39. ¶ The face, particularly the eyes and smile, reveal the quality of the soul as a moral index.Google Scholar

C82:18.DuBos, Charles. Robert et Elizabeth Browning ou La Plenitude de l'Amour Humain. Paris: Klincksieck, 1982. xiv + 177 pp. ¶ Written between the wars; the influence and meaning of their union in their works, with consideration of early works as well as works during their marriage and Rb'S after Ebb'S death. In French.Google Scholar

C82:19.Gemmette, Elizabeth V. “Browning's ‘My Last Duchess’: An Untenable Position.” SBHC, 10 (Spring 1982), 40–45. ¶ Since the Duke is unable to actualize his self (impotence, either literal or figurative), he resorts to counterfeit by dominating and controlling others.Google Scholar

C82:20. “Happenings in Browning.” The Armstrong Browning Newsletter, No. 26 (Spring 1982), p. 3. ¶ Three Browning Societies report activities.Google Scholar

C82:21. “Happenings in Browning.” The Armstrong Browning Newsletter, No. 27 (Fall 1982), pp. 2, 4. ¶ Six Browning Societies report activities.Google Scholar

C82:22.Hassett, Constance W.The Elusive Self in the Poetry of Robert Browning. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1982. viii + 175 pp. ¶ Rb'S oeuvre is unified by the poet's interest in introspection; the “confessing vein” mentioned in Paracelsus characterizes his early narratives, his mature monologues, and some of his later works. “For Browning, man is typically a convert” (p. 4). ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

C82:23.Heydon, Peter. “Annual Report of the President of the Browning Institute for 1981.” BIS, 10 (1982), 183–87.Google Scholar

C82:24.Kleefeld, Rena. “Pen's Christening Dress Restored.” Through Casa Guidi Windows: The Bulletin of the Browning Institute, No. 6 (Winter 1982/1983), p. 3. ¶ Restored outfit to be displayed in Pen Browning's birthplace.Google Scholar

C82:25.Lonoff, Sue. “MultipleNarratives and Relative Truths: A Study of The Ring and the Book, The Woman in White, and The Moonstone.” BIS, 10 (1982), 143–62. ¶ By using multiple narration both authors attempted to solve the epistemological problem of how to arrive at “the truth”; instead “they devised a method that establishes paradox on multiple levels” (p. 158).Google Scholar

C82:26.McAleer, Edward C. “The Brownings in Church and Chapel.” Through Casa Guidi Windows: The Bulletin of the Browning Institute, No. 6 (Winter 1982/1983), pp. 1–2. ¶ Religious observances of the couple, primarily in Italy.Google Scholar

C82:27.McKerrell, Alasdair. “Certainty of Experience: Dickens, with Reference to Brownings, 1883–1864.” BSN, 12 (04 1982), 2–12. ¶ Whereas Dickens overcame spiritual doubts by action, by “indubitable certainty of Experience,” as illustrated in his greatest novel, Little Dorrit, Browning, on the other hand, sought to subsume doubt into belief, as illustrated in Pauline and “A Death in the Desert.”Google Scholar

C82:28.Manson, Michael. “The Perils of Critical Algebra: A Response to Jeffrey Myers' ‘The Perils of Browning's Poets.’” SBHC, 10 (Spring 1982), 54–60. ¶ In his “Essay on Shelley” RB does not prescribe laws of poetry; rather he describes the ideal poet in literary history as one who combines objective with subjective mode, as an examination of “Fra Lippo Lippi” and other poems demonstrates.Google Scholar

C82:29.Marambaud, Pierre. “Browning et l'Art dans Men and Women.” Etudes Anglo-Americaines, 43 (1982), 41–53.* ¶ In French.Google Scholar

C82:30.Mermin, Dorothy. “Browning and the Primitive.” VS, 25 (Winter 1982), 211–21. ¶ “Essentially the Victorian interest in the primitive is the idea of evolution, or progress, turned on its head to become an obsession with origins.… To Browning the primitive suggested both innate savagery and, more disturbingly and excitingly, savage origins for poetry” (p. 216). With particular attention to the late poetry.Google Scholar

C82:31.Montiero, George. “The Presence of Camoes in Elizabeth Barrett Browning's Sonnets from the Portuguese.” BSN, 12, Nos. 2–3 (1982), 19–21. ¶ Clarifies EBB'S interest in the Portuguese poet Luis de Camoēs.Google Scholar

C82:32.Myers, Jeffrey R. “Unlooked for Perils: Michael Manson's Faulty Algebra.” SBHC, 10 (Spring 1982), 60–67. ¶ Answer to Michael Manson. [See C82:28.]Google Scholar

C82:33.Nakano, Kii. “Robert Browning to Kirisutokyo: Kare no Shi no Sai-Hyoka ni Kanren Shite.” English Language and Literature, 18 (1982), 69–81.* ¶ The poet's religion. In Japanese.Google Scholar

C82:37.Polansky, Steven Michael. “Truth of Force: Narrative Technique in Browning's The Ring and the Book.” DAI, 43 (1982), 1557A (Princeton). ¶ RB'S use of the dramatic monologue's multiple perspective in the context of various analogous narrative traditions, such as narratives of spiritual witnesses ana Luminous center narratives.Google Scholar

C82:38.Rosmarin, Adena. “The Historical Imagination: Browning to Pound.” Victorian Newsletter, 61 (Spring 1982), 11–16. ¶ In comparing Rb'S dramatic monologues such as “Cleon,” “The Bishop Orders His Tomb …” with later mask lyrics such as Pound's “The Ballad of the Goodly Frere” and other modernist works, the monologic vision where historical view returns the reader to judgment and the Victorian present is replaced by an entirely different sense of history: contradictory in that it sees time as both profoundly discontinuous and continuous.Google Scholar

C82:39.Ryals, Clydede L. “Browning's Irony,” in The Victorian Experience: The Poets, ed. Levine, Richard A.. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1982. pp. 23–46. ¶ “More than any of his immediate predecessors and contemporaries Browning is able to hold a view of the world in which the most contradictory statements to be made about it are alike true” (p. 24); with corroboration from Pauline to Asolando.Google Scholar

C82:40.Schleimer, Gloria. “Protected Self-Revelation: A Study of the Works of Four Nineteenth-Century Woman Poets, Marceline-Desbordes-Valmone, Annette Von Drosbe-Hubhoff, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, and Emily Bronte.” DAI, 42 (1982), 4413A. (University of California, Irvine). ¶ Various strategies these women employed to balance the demand of the Romantic writer to reveal intimate emotions and the expectation that women be modest and self-effacing.Google Scholar

C82:41.Shaviro, Steven. “Browning upon ‘Caliban upon Setebos.’” BSN, 12, Nos. 2–3 (1982), 3–18. ¶ A psychoanalytic perspective on Caliban's reading of the world as text: “Caliban himself may be most satisfactorily characterized as the obsessive interpreter par excellence. He reads nature as a text with a hidden author, and ceaselessly endeavors to fix within an elaborate interpretative scheme himself and everything he encounters” (p. 3).Google Scholar

C82:42.Singh, Gurdit. “Feminism in Browning's Poetry.” Punjab University Research Bulletin, 13 (04 1982), 31–36.*Google Scholar

C82:43.Slinn, E. Warwick. Browning and the Fictions of Identity. London: Macmillan Press, 1982. xi + 173 pp. ¶ “[M]y concern is with the nature of the histrionic in his poetry, with the way characters are engaged in verbal acts which dramatise themselves.” With chapters on Pippa Passes, The Ring and the Book, Fifine at the Fair, and dramatic monologues, ¶ Rev. byCrossRefGoogle Scholar

C82:44.Smith, Cornelia Marschall. The Physical Browning. Waco, Texas: Baylor University Press, 1981. xii + 60 pp. ¶ Physiology and its relation to the poetry, ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

C82:45.Solomon, Rebecca Z. “Man's Reach.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 30, No. 2 (1982), 325‐45.CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed

¶ Human aspiration and its relation to narcissism; Andrea struggles to “assuage the narcissistic wound that results from failure to achieve his goals” (p. 325).Google Scholar

C82:46.Southwell, Samuel B.Quest for Eros: Browning and Fifine. [See C80:75.] ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

C82:47.Thomas, Donald. Robert Browning: A Life within Life. New York: Viking, 1982. xiv + 334 pp. ¶ With particular attention to the later years, RB'S life can be seen as continuous in character, having a well-guarded life within whose voices become disturbingly audible in the late works. ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

C82:48.Tucker, Herbert F. JrBrowning's Beginnings; The Art of Disclosure. [See C80:81.] ¶ Rev. byGoogle Scholar

C82:49.Vann, J. Don. “The Atlas and Browning's ‘Dramatic Lyrics.’” SBHC, 10 (Fall 1982), 53–55. ¶ A perspicuous review, mistakenly entered in the Broughton, Northup and Pearsall bibliography.Google Scholar

C82:50.Walker, Cynthia L. “Lapsa-rian and Prelapsarian States in Browning's ‘Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister.’” SBHC, 10 (Spring 1982), 46–53. ¶ The speaker is intelligent, imaginative, and conscious of good and evil, whereas Brother Lawrence seems the opposite.Google Scholar

C82:51. “Victorian Modernism.” Through Casa Guidi Windows: The Bulletin of the Browning Institute, No. 6 (Winter 1982/1983), p. 4. ¶ Program description of a conference sponsored jointly by the Browning Institute and the Victorian Committee of the City University of New York.Google Scholar

C82:52.Woolford, John. “A Source for Browning's Ring Metaphor.” Notes and Queries, 227 (08 1982), 309–10. ¶ Bacon's image of a metal coin in Essay I expresses an equivocal attitude toward truth and lies; RB'S reversal of the image into a testimony about the “merely catalytic value of the imagination” (p. 310) leaves a trace of Bacon's contradictions while forcibly rewriting them.Google Scholar