Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common, inherited and disabling developmental disorder with early onset. Symptoms of ADHD often persist into adulthood. A recent meta-analysis of population-based studies across several countries estimated the pooled prevalence of adult ADHD to be 2.5% (95% CI 2.1–3.1). Reference Simon, Czobor, Bálint, Mészáros and Bitter1 However, most of the populations in these studies were unbalanced with regard to gender and age, and applied different tools to diagnose ADHD according to DSM-IV. 2 Therefore, the reported prevalence rates may not reflect the general population across these countries. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is associated with pervasive cognitive, emotional and functional impairments that affect various aspects of life, including educational, occupational and social performance. Reference Biederman, Mick and Faraone3,Reference Kessler, Adler, Ames, Barkley, Birnbaum and Greenberg4 In addition, nearly 80% of adults with ADHD present with at least one comorbid disorder, particularly anxiety disorders, affective disorders, substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder. Reference Hammerness, Surman and Miller5,Reference Rosler, Casas, Konofal and Buitelaar6 Both substance use disorder and antisocial personality disorder increase the risk for delinquency, and approximately 25–45% of adult prison inmates are estimated to have ADHD. Reference Eme7–Reference Young, Adamou, Bolea, Gudjonsson, Muller and Pitts10 Inmates with ADHD have an increased incidence of behavioural problems and comorbid psychiatric disorders, including substance use disorder and personality disorder, compared with other inmates. Reference Young, Adamou, Bolea, Gudjonsson, Muller and Pitts10–Reference Young, Wells and Gudjonsson12 According to UK guidelines issued by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), drugs are the first-line treatment for ADHD in adults with moderate or severe levels of impairment, and methylphenidate is the drug of first choice. 13 Clinical trials evaluating methylphenidate and other stimulants display short-term efficacy in both children and adults with ADHD. Reference Faraone, Spencer, Aleardi, Pagano and Biederman14,Reference Koesters, Becker, Kilian, Fegert and Weinmann15 These trials have typically excluded participants with comorbid disorders. The small number of studies evaluating methylphenidate for participants with ADHD and comorbid substance use disorder has not been able to establish efficacy against ADHD. Reference Adler, Spencer, McGough, Jiang and Muniz16 The long-term effectiveness, safety and tolerability of methylphenidate is not well understood as there have been few long-time follow-up studies. Reference Adler, Spencer, McGough, Jiang and Muniz16–Reference Wender, Reimherr, Marchant, Sanford, Czajkowski and Tomb19 Despite the high prevalence of ADHD in prison inmates, pharmacological treatment has not been evaluated in this group. This is likely due to concerns about safety and misuse of the drug therapies by this patient population, and the challenge of conducting pharmacological trials in prison settings. Reference Eme7–Reference Young, Adamou, Bolea, Gudjonsson, Muller and Pitts10

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy, long-term effectiveness, safety and tolerability of osmotic-release oral system (OROS) methylphenidate in adult long-term prison inmates with ADHD and comorbid disorders. The OROS methylphenidate was delivered at a daily dose of 72 mg compared with placebo over a 5-week period, followed by an open-label extension with OROS methylphenidate delivered at a flexible dosage of up to 1.3 mg/kg daily over a 47-week period.

Method

Participants

Eligible participants were adult male prison inmates, aged 21–61 years, with ADHD according to DSM-IV criteria. 2 All inmates were hosted at Norrtälje Prison, a high-security prison outside Stockholm, Sweden, for long-term, adult male inmates, typically convicted of violent or drug-related crimes. The initial screening survey and diagnostic assessments have been previously reported. Reference Ginsberg, Hirvikoski and Lindefors8 Briefly, inmates hosted at Norrtälje Prison between December 2006 and April 2009 were approached for screening for both childhood and adulthood ADHD by self-reported questionnaires. All inmates were approached except those deemed too mentally unstable and those to be deported from Sweden after serving their sentence. The aim was to recruit 30 eligible participants with established ADHD to the randomised clinical trial (RCT): participants were initially selected on the basis of the ADHD questionnaires, with diagnosis subsequently confirmed in comprehensive assessments by experienced board-certified psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. Participants were mainly recruited from Stockholm County, and had at least 14 months left until conditional release to ensure completion of the trial. The study was approved by the Ethical Board of Stockholm, Sweden (2006/1141-31/3) and the Swedish Medical Products Agency (EudraCT-nr 2006-002553-80). The trial is registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT00482313). Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after they had received a thorough description of the study. To validate adherence to good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki, the trial was independently monitored by the Karolinska Trial Alliance and inspected by the Swedish Medical Products Agency respectively.

Clinical assessments

The assessments included the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), Reference Lobbestael, Leurgans and Arntz20 the Hare Psychopathy Checklist – Revised (PCL-R), Reference Hare, Clark, Grann and Thornton21 a self-rated version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders, the SCID II Patient Questionnaire (SCID-II-PQ), Reference Lobbestael, Leurgans and Arntz20 and a structured interview confirming ADHD consistent with DSM-IV. 2 Additional assessments included a medical history, a physical examination, routine laboratory tests, urinary drug screening and neuropsychological tests assessing IQ and executive functions. When appropriate, additional evaluations were performed for autism-spectrum disorder in accordance with DSM-IV. 2 Finally, the assessments included obtainment of information from parents by questionnaires and interviews, and collection of records from school, health services, and the prison and probation service, regarding childhood history and present symptoms and functioning.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To enter the trial, participants had to have confirmed ADHD in accordance with DSM-IV and to agree not to behave violently during the study. Participants with comorbid disorders such as autism-spectrum disorder, anxiety and depression could take part if they were considered to be stable at baseline. Previous drug-elicited episodes of psychosis were not a cause for exclusion, other than chronic psychoses. Concurrent medication not interfering with methylphenidate was permitted for treating comorbid disorders, as long as doses were stable for at least 1 month at baseline. Medications interfering with methylphenidate had to be tapered off before the baseline visit took place. Participants were excluded if they were known to be non-responsive or intolerant to methylphenidate, or intolerant to lactose. In addition, participants were excluded if they showed evidence of substance misuse up to 3 months before baseline, assessed in urine samples. Intellectual disability, epilepsy, glaucoma, uncontrolled hypertension, angina pectoris, cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac abnormality or a family history of serious cardiac illnesses were exclusion criteria, but hepatitis C without liver insufficiency did not preclude inclusion.

Randomisation and masking

Participants were randomly assigned in equal numbers to either the placebo or the OROS methylphenidate group according to a parallel-group design. The pharmacy laboratory assigned participants to the two study groups using a random number table prior to preparing and dispensing the study drug according to the study protocol. The random number table was stored in the pharmacy department and was concealed from study staff and participants until completion of the study. The placebo and methylphenidate capsules and packaging were identical in appearance and were coded with a unique randomisation number.

Intervention

Both study staff and participants were masked to assignment during the RCT. Participants were consecutively randomised in the order that they were enrolled by the investigator. The study drug was titrated from 36 mg/day for 4 days to 54 mg/day for 3 days and then to 72 mg/day for the remaining 4 weeks. All participants completing the 5-week RCT were eligible to enter the 47-week open-label extension, starting the day after completion of the 5-week RCT. During the open-label extension, methylphenidate was titrated from 36 mg/day to determine the optimal response and tolerability, but not exceeding 1.3 mg/kg daily. In case of adverse events, downward titration was allowed, followed by upward titration once the participant had recovered. In addition to medication, all participants received personal psychosocial treatment as part of prison routine, including school activities according to the Swedish curriculum and cognitive programmes addressing addiction, criminality, aggression and social skills. The psychosocial treatment did not specifically address ADHD.

Primary outcome measure

The primary efficacy outcome was the change in ADHD symptoms from baseline until completion of the RCT at end of week 5, as measured by the total sum-score of the Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale – Observer: Screening Version (CAARS-O:SV), Reference Rosler, Retz and Stieglitz22 which is one of the most widely used expert rating scales in clinical trials evaluating adult ADHD. This strictly DSM-IV-oriented 18-item Likert scale includes relevant psychometric properties based on US norms. Although it has been widely used internationally, including Sweden, its use has not been formally evaluated in non-English speaking countries. Reference Rosler, Retz and Stieglitz22

Secondary outcome measures

The frequency of adult ADHD symptoms corresponding to DSM-IV criteria were reported by participants using the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS). Reference Rosler, Retz and Stieglitz22 This 18-item Likert scale includes relevant psychometric properties based on US norms. The ASRS also lacks Swedish validation, but is widely used in clinical practice. Symptoms of ADHD during the open-label extension were evaluated by the masked assessor using CAARS-O:SV. Also, overall severity from ADHD using the Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale (CGI-S) Reference Guy23 and psychosocial functioning using the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF), Reference Ramirez, Ekselius and Ramklint24 were evaluated by the same assessor, from baseline until end of week 52.

Treatment response rate and numbers needed to treat (NNT) were determined post hoc.

Changes in neuropsychological functioning, quality of life and institutional behaviour during the course of the study were also evaluated; these findings will be reported in a subsequent paper.

Procedures

The screening visit took place up to 2 weeks before randomisation to enable medications excluded from the study to be tapered off prior to the baseline visit. In most cases, the same specifically trained and masked assessor performed the evaluations of CAARS-O:SV, CGI-S and GAF at baseline and weeks 1, 3, 5, 8, 16, 32 and 52. The self-reported ASRS was also administered at these visits. Body weight was recorded at baseline and weeks 5, 8, 12, 20, 32, 44 and 52. Adverse events, blood pressure and heart rate were obtained at all study visits. In addition, prison staff regularly supervised urinary drug screenings as part of general prison routines. To certify adherence to the protocol, study staff supervised and documented delivery of the study drug. All packages, documentation and remaining drugs were returned to the primary investigator at the end of the study for evaluation of adherence to the study protocol.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics summarised demographics, clinical characteristics and outcome scores at baseline. Paired t-tests were performed for changes within participants over time and mixed between–within participants ANOVA for changes from baseline through to the final visit of the RCT, using SPSS 17.0 for Windows for both outcome and safety measures, including cardiovascular measures and body weight. All analyses were intention-to-treat (ITT) using last observation carried forward (LOCF), including all randomised participants, with two-sided significance set at P = 0.05. Non-parametric statistics were used for outcomes measured by Likert scales. As results for parametric and non-parametric tests were similar, only parametric statistics are presented. Single missing values were handled conservatively by substituting the missing value with the higher value from the preceding or following visit. The effect size was analysed using Cohen’s d for efficacy measures. Post hoc, the treatment response rate and NNT for treatment response were determined.

Sample size

Based on preliminary findings and previous studies, Reference Faraone, Spencer, Aleardi, Pagano and Biederman14,Reference Medori, Ramos-Quiroga, Casas, Kooij, Niemela and Trott25,Reference Spencer, Biederman, Wilens, Doyle, Surman and Prince26 the aim was to detect a mean difference of 9 units in the CAARS-O:SV (range 0–54) between groups from baseline until the end-point at week 5. Power was 90%, significance level was 0.05 (two-sided) and s.d. = 7. With treatment assignment at a 1:1 ratio and allowing for a 20% drop-out rate, the aim was to recruit 30 participants.

Results

Participants

Of 34 assessed inmates, 9 had previously been diagnosed with ADHD, including 2 during childhood. Five inmates had previously been treated with methylphenidate, one of them during childhood, for no more than a few months. None of the inmates were known to be non-responsive or intolerant to methylphenidate.

Clinical assessments confirmed that 30 of the inmates had ADHD. All consented and were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to placebo or OROS methylphenidate 72 mg daily, between May 2007 and April 2009 (Fig. 1). Most participants were initially hosted in a dedicated ADHD wing for 12 inmates, as decided by Norrtälje Prison. This wing was separate from other wings to prevent exchange of drugs. The prison officers in the wing were educated by the investigators about ADHD. Inmates were relocated to ordinary prison wings once their participation in the trial was completed. A small number of participants carried out the trial in other special wings, such as the wing for sexual offenders.

Baseline characteristics were largely similar between study groups, as shown in online Table DS1. Comorbid disorders were common; all reported lifetime substance use disorder, all but one presented antisocial personality disorder, a majority had mood and anxiety disorders, and a quarter had confirmed autism-spectrum disorder. At baseline, almost half of the participants were receiving concurrent treatment for mood and anxiety disorders. Baseline scores on CAARS-O:SV, ASRS, CGI-S and GAF show that the participants had severe ADHD and low psychosocial functioning at entry.

Intervention

All participants received the assigned treatment and completed the 5-week RCT; no one dropped out. All 30 participants subsequently entered the 47-week open-label extension, ending in April 2010. The open-label extension was completed by 24 participants. However, 25 participants provided end-point data for the open-label extension as we assessed one participant at week 46, just prior to advanced release from prison. Figure 1 presents time and reasons for discontinuation. Participants who first received placebo treatment were more likely to drop out compared with those who initially received OROS methylphenidate. The ITT and safety analyses using LOCF included all 30 participants. Treatment adherence was excellent; 99% for the RCT and 98% for the open-label extension. However, symptom relief did not last long enough for a few participants with once daily delivery. Therefore, we modified the study protocol to permit delivery of OROS methylphenidate twice daily during the open-label extension, in the morning and at noon, to maintain symptom relief throughout the day. At end-point week 52, the mean dose was 105 mg daily (s.d. = 27.2) or 1.22 mg/kg daily (s.d. = 0.28).

Primary outcome measure

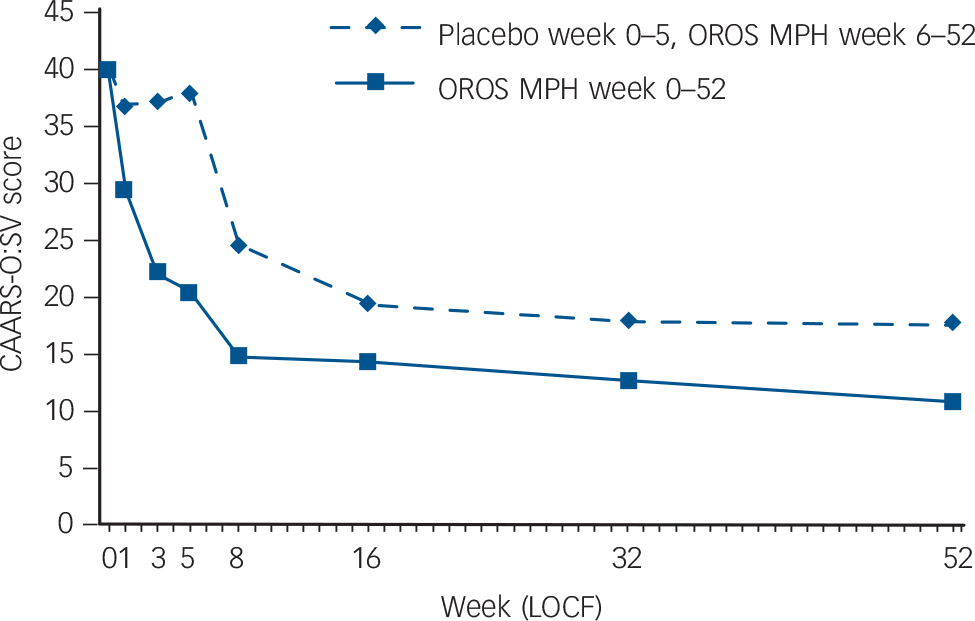

Mean scores for the primary outcome measure, CAARS-O:SV, were significantly decreased by 19.6 (95% CI 14.7 to 24.5) in the methylphenidate group (P<0.001) compared with a non-significant decrease of 1.9 (95% CI –0.4 to 4.2) in the placebo group. The effect size was exceptionally large, with a Cohen’s d score of 2.17 (online Table DS2 and Fig. 2).

Secondary outcome measures

Change in CAARS-O:SV was also measured from the completion of the RCT (week 5) to the end of the open-label extension (week 52). Scores for CAARS-O:SV improved in both groups over the course of the open-label extension; those who switched from placebo to OROS methylphenidate after 5 weeks improved more than those who received OROS methylphenidate for the full 52 weeks (online Table DS2 and Fig. 2). Over the entire 52-week period, participants who received placebo during the first 5 weeks did not improve as much as those who received OROS methylphenidate from the start (online Table DS2 and Fig. 2).

Other secondary outcomes were changes in ASRS, CGI-S and GAF during both the RCT and the open-label extension. As shown in online Table DS2, the OROS methylphenidate group significantly outperformed placebo on all outcome measures during the RCT (ASRS, P = 0.003; CGI-S, P<0.001; and GAF, P = 0.004). All outcome measures also improved in both groups during the open-label extension. In summary, the OROS methylphenidate group improved considerably during both phases, whereas the improvement of the placebo group was insignificant during the RCT but was substantial during the open-label extension. Over the entire 52-week study, those who received

Fig. 1 Participant flow and reasons for dropping out throughout the trial. ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

OROS methylphenidate from the start improved the most (online Table DS2).

Post hoc, when applying the original definition of treatment response (≥30% decrease of CAARS-O:SV at week 5), 87% responded to OROS methylphenidate treatment compared with 0% for placebo; NNT was 1.1 (95% CI 1–2). The extent of response in individual participants is shown in Table 1, with marked responses observed in the methylphenidate group.

Adverse events

Adverse events occurred more frequently in the methylphenidate group than in the placebo group during the RCT. However, mucosal dryness was the only adverse event that significantly differed between study groups, being more frequently reported in the OROS methylphenidate group. No serious adverse event was recorded during the RCT (data not shown). There was one discontinuation during the open-label extension due to a serious adverse event (Fig. 1); one participant became unconscious at week 9 and was sent to hospital, where he recovered spontaneously. As we could not identify the underlying cause, we immediately stopped medication and withdrew the participant from the trial. The most common adverse events associated with the study drug were abdominal discomfort, headache, mucosal dryness, depressed mood, loss of appetite, anxiety, diarrhoea, sweating, interrupted sleep and fatigue. The intensity of these adverse events was generally mild to moderate and they were not considered to justify removal from the study (data not shown). Regular supervised urinary drug screening did not reveal any drug misuse during the course of the study.

Safety measures

There were no significant changes in systolic or diastolic blood pressure, heart rate or body weight in either group during the RCT. Over the entire 52-week study period, systolic blood pressure in the methylphenidate group increased by 21.5 mmHg (95% CI 8.9–34.0) and diastolic blood pressure increased by 11.0 mmHg (95% CI 4.9–17.1). There were no changes in heart rate or body weight between study groups. Heart rate increased by 13.2 beats per minute (95% CI 7.0–19.4) from baseline until week 52 in the group that initially received the placebo; body weight, systolic and diastolic blood pressure remained unchanged (online Table DS3).

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, OROS methylphenidate was significantly better than placebo in reducing symptoms of ADHD in adult prison inmates with ADHD and comorbid disorders, including lifetime substance use disorder, in a 5-week RCT. The therapeutic effect of OROS methylphenidate continued to improve during the 47-week

TABLE 1 Treatment response among participants in both study groups during the 5-week randomised controlled trial

| Treatment response, % a | OROS-MPH (n = 15) | Placebo (n = 15) |

|---|---|---|

| None (≤0) | 1 | 2 |

| Small (1–25) | 1 | 13 |

| Moderate (26–50) | 6 | 0 |

| High (51–75) | 7 | 0 |

OROS-MPH, osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate.

a Treatment response defined as % decrease of the total sum-score of Conners' Adult ADHD Rating Scale – Observer: Screening Version from baseline until end of the trial at week 5.

open-label extension. The treatment was safe and well-tolerated with the exception of one serious adverse event, and despite a high prevalence of lifetime substance use disorder, no drug misuse was detected during the course of the study. Amphetamine was the most commonly reported lifetime drug of choice in this group, raising the question of whether the initial use of amphetamine was an attempt to self-medicate symptoms of ADHD.

In contrast to most previous treatment studies of adult ADHD, we did not exclude participants with current treatment for comorbid disorders, unless the concurrent treatment interfered with the activity of methylphenidate. This allowed us to extend the external validity of the results to a broader ADHD population. Reference Surman, Monuteaux, Petty, Faraone, Spencer and Chu27 All participants presented comorbid lifetime substance use disorder and, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to establish the efficacy of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD combined with substance use disorder. Reference Koesters, Becker, Kilian, Fegert and Weinmann15 Although our findings on the efficacy, effectiveness and safety of methylphenidate treatment of adult ADHD are consistent with previous studies, Reference Koesters, Becker, Kilian, Fegert and Weinmann15,Reference Adler, Spencer, McGough, Jiang and Muniz16,Reference Wender, Reimherr, Marchant, Sanford, Czajkowski and Tomb19 the effect size of d = 2.17 was substantially greater than that reported in other studies; for example, previous studies have reported effect sizes ranging from d = 0.42 to a maximum of d = 1.408. Reference Faraone, Spencer, Aleardi, Pagano and Biederman14,Reference Koesters, Becker, Kilian, Fegert and Weinmann15 The placebo effect was negligible in this study, in sharp contrast to the significant placebo responses that have been reported in most previous studies. We propose several explanations for these distinctive results. Participants in our study had particularly severe ADHD, leaving a large window for improvement by methylphenidate. In addition to the high baseline ADHD scores, all participants were male and had a

Fig. 2 Intention-to-treat population: Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scale – Observer: Screening Version (CAARS-O:SV) total sum-score as a function of treatment group and time.

Randomised controlled trial: week 0–5; open-label extension: week 6–52. OROS-MPH, osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate; LOCF, last observation carried forward.

history of poor academic achievement. These three factors have been previously suggested as predictors of superior treatment outcomes in adults with ADHD. Reference Buitelaar, Kooij, Ramos-Quiroga, Dejonckheere, Casas and van Oene28 The negligible placebo response also contributed to the large treatment effect and we suggest that the high level of ADHD symptoms in the participants also made them less likely to benefit from placebo treatment, consistent with the results of Levin et al. Reference Levin, Evans, Brooks, Kalbag, Garawi and Nunes29 In our study, diagnostic specificity was likely to be very high due to the comprehensive ADHD assessments that we performed, and this may also have contributed to the large effect size by minimising the number of incorrectly diagnosed study participants. In addition, we achieved excellent treatment adherence, probably due to the structured and controlled setting of the dedicated ADHD wing. This controlled setting may also have contributed to the absence of drug misuse of the study drug. Finally, all participants completed the RCT, thus preserving statistical power.

Limitations and strengths

The limitations of the present study need to be considered. The sample size was small, although the results were highly significant in the RCT. The open-label extension lacked a control group, and it is difficult to predict how a placebo group may have behaved over the full 52 weeks. The study setting was highly specific, involving long-term male inmates of a high-security prison with ADHD together with comorbid disorders, and generalisation to other populations may not necessarily be valid. However, the inclusion of participants with comorbid disorders with concurrent treatment for these disorders increased the external validity of the results as most adults with ADHD present with comorbid disorders.

Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate pharmacological treatment of prison inmates with ADHD. Future studies will need to confirm our result in other prison populations. Studies evaluating other pharmacological options and supplementary cognitive–behavioural treatment, and the impact of treatment on relapse into drug misuse and criminality are also warranted. Reference Young, Adamou, Bolea, Gudjonsson, Muller and Pitts10 We propose that future studies of ADHD include comorbid disorders in their inclusion criteria, and that they extend treatment evaluation to include behavioural variables, executive functioning and quality of life.

We conclude by suggesting that OROS methylphenidate can be a viable, effective and safe treatment for ADHD in a prison setting with a well-structured and strictly controlled environment to prevent drug misuse and diversion. Considering the high prevalence of untreated ADHD in prison inmates, Reference Ginsberg, Hirvikoski and Lindefors8–Reference Young, Adamou, Bolea, Gudjonsson, Muller and Pitts10 further research on treatment of prison inmates is warranted to confirm and expand upon our findings.

Funding

The Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs and Stockholm County Council, Sweden, funded this study.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants, the staff at Norrtälje Prison and the psychiatrists and psychologists who assisted in the conduct of the trial. We especially acknowledge Michaela Wallensteen, RN (Stockholm County Council) for serving as the masked evaluator, Birgitta Strandberg, RS, BSc (Karolinska Trial Alliance) for monitoring the study, Monica Hellberg, RN (Stockholm County Council) for providing administrative assistance and Stefan Ginsberg for providing administrative assistance and valuable comments on the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.