Max Glatt, by the narrowest of margins, succeeded in escaping the Holocaust. His parents, as he discovered much later, were less fortunate: they were slaughtered in an Estonian concentration camp leaving him and a sister, who had been smuggled out of Germany into Holland, as the sole survivors of his entire family.

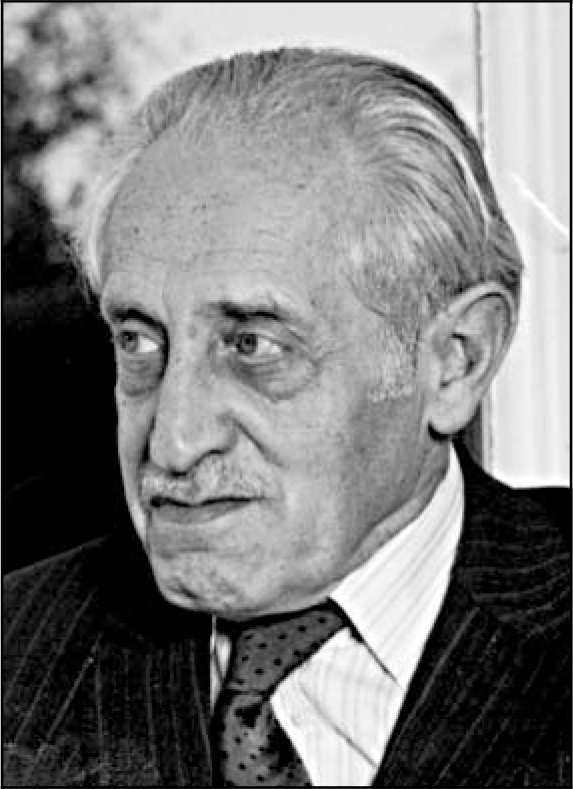

Max was born in Berlin on 26 January 1912 into a prosperous, middle-class Orthodox Jewish family. His Judaism was then, and remained, central to his life despite all the difficulties involved in keeping the complex beliefs and practices of orthodoxy, particularly in the Diaspora.

Max's career as an undergraduate in the 1930s was blighted by the rise of Nazism, particularly the malignant persecution of the Jews. Nevertheless, in 1937, he was awarded his MD at the University of Leipzig. By that time, the poison of anti-semitism had seeped into every layer of the German medical establishment so that further academic progress was blocked, practice in any general hospital was forbidden by diktat, and the only work available for Max, as a Jew, was in a small hospital in Berlin which served exclusively Jews. Even so, his innate optimism coupled with, apparently, a degree of political naivety, caused him to hang on. And hang on he did until the momentous events of Kristallnacht shattered the last vestiges of optimism: the message on the wall was clearly written, not in chalk, but in blood.

Max put his escape plan into effect. The plan in the event was shot through with failures, and it is a near-miracle that he finally succeeded in arriving safely in England (for the second time). And it was in England that, in 1942, Max resumed, or was permitted to resume, medical practice, fortunately, as it happened, in mental hospitals controlled by the London County Council Mental Health Department.

But in which direction should he point his genius and his hunger for work? It was probably his own personal suffering as a member of a persecuted minority, plus his deep-seated compassion for the underdog, that led him to seek out a neglected and best-forgotten section of the community. And what better example could he find than those he saw around him every day in the back wards in mental hospitals, among the frequenters of park benches or pavement-sleepers — to wit, those suffering from alcohol or drug misuse? These, he decided, were the people to whom he would devote his professional life and with missionary zeal he set to work.

His first NHS unit for the treatment of alcoholism was established at Warlingham Park Hospital near Croydon, South London, to be followed by another for alcoholism and drug addiction at St Bernard's Hospital, Ealing, West London, now named the Max Glatt Centre. In theory, both units were based on group and/or community principles and, as his fame spread, so further units were established in the NHS, in the private sector and within the prison service, the best known being that at HMP Wormwood Scrubs.

Max was a prodigious worker. He served as an honorary consultant psychiatrist at four London teaching hospitals as well as acting as chair or member of innumerable committees. His advice was sought by important bodies such as the British Medical Association, the Home Office, the Royal medical colleges and councils concerned with the problems of alcoholism and drug addiction. To cap it all, he was appointed a part-time lecturer at several universities.

Tangible rewards began to flood from universities and academic bodies at home, and particularly, from abroad, who fell over themselves to award him prizes and honorary degrees. In 1970, The Royal College of Physicians of London elected him MRCP, to be elevated to FRCP in 1975. The Royal College of Psychiatrists elected him to the Foundation Fellowship in 1971, and in 1985 he was elected to the Honorary Fellowship. Prestigious prizes were heaped on him in America and, ironically, in Germany. It is worthy of comment that the suffering experienced at the hands of the Nazis failed to quench his love for Berlin, to which he returned whenever the occasion arose.

Max was a prolific writer. He proved as nimble with his pen as he was with a table tennis bat. This simile is apt because, surprisingly, he was an excellent and stylish table tennis player, who had represented Berlin as a student and at a senior club in Croydon much later. Having mastered the English language, Max's contribution to the literature was enormous. Inter alia, by 1982 he had contributed 30 papers in the UK and abroad, written 9 chapters in important books and, as a single author, had published 4 books, all of them now classics. What is more, Max was a skilled editor. Between 1961 and 1978, he transformed Addiction from a parochial British journal into a publication of worldwide repute.

But Max, albeit a physician of the utmost fame, remained modest, gentle and good-humoured throughout his life. His love for his family was matched only by his devotion to and the strength he gained from his Judaism.

But what drove him relentlessly on was work; work was always the name of the game. He never retired and he died, as he would have chosen to do, with his boots on. The end came on 14 May 2002, the spread of advanced prostate cancer was responsible, in all probability, for the fall he sustained while conducting his weekly group at the Florence Nightingale Hospital. He was in his 90th year.

He leaves his wife, Gisella, herself a Holocaust survivor, his son Julian, two grandchildren and a host of grateful patients.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.