No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Ontogenesis of Resin Ducts and Secretory Process in Protium spruceanum (Burseraceae) Stems

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 March 2022

Abstract

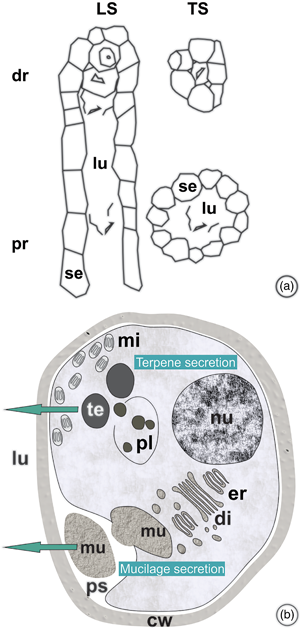

The objective of this work was to characterize the ontogenesis of Protium spruceanum secretory ducts, to evaluate the effects of seasonality on that process, and to characterize the chemical nature of the resin. Morphometric, anatomical, micromorphometric, histochemical, and ultrastructural evaluations of shoot apexes and chemical analyses of the resin were performed. The ducts of schizolysigenous origin are distributed in the primary and secondary phloem. The subsecretory tissue is meristematic and can restore the secretory epithelium. Secretory epithelial cells have wall thickening resembling that of the Casparian strip that regulates secretion reflux. The main resin compounds are pentacyclic triterpenoids, α- and β-amyrins, and α- and β-amyrenones, which are reported here for the first time for this species. The presence of electron-dense and electron-opaque structures, in the secretory epithelial cells, are compatible with the triterpenes and mucilage identified in the resin. Rising temperatures, rainfall, and increasing day length induce the formation of ducts in the vascular cambium throughout Spring/Summer. The abundant production of resin rich in pentacyclic triterpenes indicates the potential use of the species for medicinal and cosmetic purposes. The understanding that secretory processes are concentrated during the Spring/Summer seasons will contribute to the definition of resin extraction management strategies.

- Type

- Biological Applications

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2022. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Microscopy Society of America