A considerable body of research has investigated the hypothesis that courts, through their institutional legitimacy, can persuade citizens to change their views on the substantive issues of judicial rulings, or at least to acquiesce to decisions with which they disagree.Footnote 1 Most of this research relies upon an implicit model of attitude change in which citizens are thought to consciously mull over the legal arguments of courts (e.g., is the death penalty “cruel?”) and adjust their views accordingly. Or, relatedly, citizens may be stimulated to think about judicial power, fairness, and legitimacy, and therefore accept that the institution has the right to make authoritative decisions requiring acceptance. The key element in this process is assumed to be some form of conscious thinking and deliberation.

Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson and Caldeira (2009) have put forth “Positivity Theory” in which they suggest that when citizens pay attention to courts, they are influenced by the pageantry of judicial symbols, and that this, too, contributes to acquiescence and attitude change. People may be impressed by such symbols as the robes of judges, the honorific forms of address, and the temple-like buildings in which courts are typically housed. Judicial scholars often simply assume the importance of these symbolsFootnote 2; systematic empirical investigations of their effects are, however, practically nonexistent.

This article reports the results of a survey-based experiment that examines the influence of exposure to judicial symbols on acquiescence to an unwanted Supreme Court decision. Overall, we discover that the symbols of judicial authority play a crucial moderating role in the legitimacy–acquiescence linkage, with judicial symbols changing the way attributions of legitimacy get connected to acquiescence to a disagreeable Court decision. For the bulk of Americans with little prior exposure to the Supreme Court, the presence of judicial symbols strengthens the link between institutional legitimacy and acceptance of the decision. Without exposure to the symbols, greater institutional legitimacy still contributes to more acceptance of a Supreme Court decision but much more weakly. In addition, not everyone holds the same degree of reverence for the Supreme Court, and consequently the impact of exposure to judicial symbols is contingent upon preexisting levels of support. Finally, the presence of judicial symbols impedes the translation of policy disappointment into a willingness to challenge the Court and its policies. We conclude our analysis with some speculation about the micro-level mechanisms through which symbols exert their influence.

Positivity Theory and Acquiescence to Objectionable Court Rulings

The U.S. Supreme Court is widely regarded as one of the most legitimate judicial institutions in the world (see Reference Gibson, Caldeira and BairdGibson, Caldeira, and Baird 1998). As a consequence, the Court has been able to serve as an effective policy maker in American politics. Judicial legitimacy's power lies in its ability to induce acquiescence to court decisions with which citizens disagree, and in this sense legitimacy presumes an objection precondition. Legitimacy is for losers, since winners ordinarily accept decisions with which they agree (Reference GibsonGibson 2014a). Especially since American courts are bereft of the conventional means of eliciting compliance with unpopular decisions (without the proverbial purses and swords), legitimacy is indispensable for institutions whose very job often includes thwarting the will of the majority.

Consequently, scholars have invested considerable effort in examining the legitimacy–acquiescence linkage. Two streams of research have evolved. First, some studies focus on the ability to create substantive attitude change. In this body of research, a handful of projects, conducted mainly in the United States (but see Reference Baird and JavelineBaird and Javeline 2007), have assessed the impact of court rulings on the distribution of public opinion on policies germane to the court ruling (e.g., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and SpenceGibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2005; Reference MarshallMarshall 2008; Reference MondakMondak 1994).

An important finding of research on attitude change is that the effect of Supreme Court decisions is conditional upon the context and up on citizens' preexisting attitudes. For example, to the extent that citizens view a court decision as grounded in partisan politics, rather than legal reasoning, it is unlikely that the decision will generate attitude change (see Reference Baird and GanglBaird and Gangl 2006; Reference Gibson, Caldeira and SpenceGibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2005; Reference HumeHume 2012). Furthermore, since citizens must rely on third parties to provide information about decisions, opinion change depends on the informational context and the style of information presented in the media (see Reference Brickman and PetersonBrickman and Peterson 2006; Reference Clawson and WaltenburgClawson and Waltenburg 2003; Reference Slotnick and SegalSlotnick and Segal 1998). Citizens' legitimacy attitudes and perceptions of the decision-making process condition the ability of courts to influence public opinion.

A second body of work investigates the degree to which legitimacy converts into acceptance of or acquiescence to unpopular court decisions. Cross-national research indicates that legitimacy is not always sufficient to produce acquiescence, especially in relatively young courts (e.g., Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson and Caldeira 2003), but research in the United States has generally supported the hypothesis that legitimacy can induce acquiescence (see Reference Gibson, Caldeira and SpenceGibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2003a, Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2005). The decisions of legitimate institutions, even when handing down unpopular decisions, seem to carry with them an obligation to accept and obey (Reference Levi, Sacks and TylerLevi, Sacks, and Tyler 2009; Reference TylerTyler 1990, Reference Tyler2006; but see Reference Nicholson and HansfordNicholson and Hansford 2014).

By what mechanisms do courts acquire and mobilize acquiescence-enhancing legitimacy? Perhaps the dominant explanation of the process is the Reference Gibson and CaldeiraPositivity Theory of Gibson and Caldeira (2009). That theory begins by noting an asymmetry between pleasing and displeasing decisions. When citizens are confronted with a decision with which they agree, they rarely seek an explanation; instead, they simply credit the institution for acting wisely (Reference Lodge and TaberLodge and Taber 2013).Footnote 3 However, when confronted with a displeasing decision, they do not punish the institution to the same extent as they reward it for a pleasing one.Footnote 4 Gibson and Caldeira dub this unusual asymmetry “Positivity Theory.”

This positivity bias is reinforced by exposure to powerful symbols of judicial authority. When citizens pay attention to judicial proceedings, they are bombarded with a host of specialized judicial symbols, typically beginning with the court building itself (often resembling a temple—see Reference ResnikResnik 2012), and proceeding through special dress for judges (robes), and honorific forms of address and deference (“your honor”), directed at a judge typically sitting on an elevated bench, surrounded by a panoply of buttressing symbols (a gavel, the blind-folded Lady Justice, balancing the scales of justice, etc.). These judicial symbols frameFootnote 5 the context of court decisions and seem to convey the message that courts are different from ordinary political institutions; that a crucial part of that difference is that courts are especially concerned about fairness, particularly procedural fairness; that because decisions are fairly made, they are legitimate and deserving of respect and deference; and consequently that a presumption of acquiescence attaches to the decisions.Footnote 6 Thus, the Supreme Court's legitimacy is sustained, reinforced, and empowered by exposure to the strong and pervasive symbols of the authority of law and courts—according to Positivity Theory.

A Theory of Motivated Political Reasoning and the Activation of Thoughts About Institutional Legitimacy

Some empirical evidence has been adduced in support of Positivity Theory. What is missing, however, is any empirical substantiation that judicial symbols influence citizens. More importantly, a theory by which symbols communicate with citizens has not heretofore been advanced in the area of judicial politics.

A useful means of looking inside the black box of Positivity Theory has been proposed by Reference Lodge, Taber, Lupia, McCubbins and PopkinLodge and Taber (2000, Reference Lodge and Taber2005, Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Reference Taber, Cann and KucsovaTaber, Cann, and Kucsova 2009; Reference Taber and LodgeTaber and Lodge 2006). Building on three decades of cognitive science research, their Theory of Motivated Political Reasoning posits dual processing on a bicameral structure of memory. Central to the theory is a distinction between subconscious (“System 1”) and conscious (“System 2”) information processing for judgments, preferences, and decisionmaking (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2012). System 1 processes operate outside conscious awareness, are relatively spontaneous, fast, unreflective, and effortless, whereas System 2 processes are conscious, slow, deliberative, and effortful, and are bounded by the small capacity and serial processing limitations of conscious working memory (Reference MillerMiller 1956).

In System 1, affective and cognitive reactions to a stimulus are triggered unconsciously and spread activation through associative pathways (Reference Collins and LoftusCollins and Loftus 1975; Reference NeelyNeely 1977). Environmental events trigger these automatic mental processes within a few hundred milliseconds of registration, beginning with a subconscious appraisal process that matches the stimulus to memory objects. Shortly thereafter, positive and/or negative feelings associated with these memory objects are aroused (Reference FazioFazio et al. 1986; Reference ZajoncZajonc 1980). Based on the automatic activation of objects and their affective and cognitive associations, processing goals are established by these associations (Reference BarghBargh et al. 2001; Reference KayKay et al. 2004), and these goals motivate the depth and “direction” of downstream deliberative processing (Reference Lodge and TaberLodge and Taber 2013).Footnote 7 Through previously learned mental associations, the first subconscious steps down the stream of processing establish the rudimentary meaning of the event, positive or negative affect, and motivational goals. The associations, rudimentary meanings, and goals activated by this stimulus then enter conscious processing and the operations of System 2 begin. Thus, only at the tail end of the decision stream does one become consciously aware of the associated thoughts and feelings unconsciously generated moments earlier in response to an external stimulus.

This Theory of Motivated Political Reasoning fits well with Positivity Theory. Whenever a person sees a judicial symbol, System 1 automatically triggers learned associated thoughts, which for most people in the United States have become connected with these symbols largely through socialization processes (Reference Sears and KuklinskiSears 2001) and experience (Reference Benesh and HowellBenesh and Howell 2001; Reference SilbeySilbey 2005), and which are typically ones of legitimacy and positivity. This activation leads to more conscious legitimating and positive thoughts in System 2, causing people to be motivated to accept the court's decision. Thus, the unconscious processes of System 1 feed legitimating thoughts to System 2, fundamentally changing the motivations and thoughts that people bring to the decision about whether to accept a judicial decision. This is because the symbols have activated a broader (or at least different) set of considerations, making such facts, figures, and values more readily accessible in working memory, and therefore more influential on downstream information processing and decisionmaking (see Reference Lodge and TaberLodge and Taber 2013).

We acknowledge that connected thoughts may be activated and made available for use in subsequent processing of stimuli through processes not involving exposure to symbols. For judicial politics scholars, for instance, the mere mention of the Supreme Court is most likely sufficient to activate a wide and deep network of thoughts about the Court. Because we can imagine nonsymbols-based processes, the most useful research design is one that allows us to pinpoint the specific, independent effect of exposure to symbols—as in an experimental design such as the one we employ in this research. We hypothesize that respondents who are asked to evaluate a Supreme Court decision after being exposed to the symbols of judicial authority react differently from those not exposed.

As noted, legitimacy is for losers. We speculate that when people are confronted with a Supreme Court decision that they oppose, it is natural to think about what can be done in response. Simple, affect-driven, motivated processing can be pretty succinct: “I don't like the decision and I therefore want to see what can be done to reverse it.” When asked whether such a decision should be accepted and acquiesced to, many would say “no way!”

However, when thoughts about judicial legitimacy are readily accessible in working memory (because they have been previously activated), thought processes may become more deliberative. One common additional responseFootnote 8 would be to question how the decision was made—for example, was the decision-making process fair?—and then to consider whether the decision is “legitimate” and whether it can and should be challenged. One might not like a decision, but thoughts about legitimacy are often juxtaposed against any such dissatisfaction, thereby increasing the likelihood of acquiescence. Although the statistical relationships are decidedly more complicated than implied here (see below), our basic hypotheses are (1) that the presence of symbols activates more expansive mental processing about Supreme Court legitimacy, and (2) that acquiescence to an objectionable Court decision is more likely when considerations of legitimacy enter the decision-making calculus.

Some psychologists have reported experimental results indicating that political symbols do indeed have the type of effect we hypothesize here. For example, Reference Butz, Plant and DoerrButz, Plant, and Doerr (2007) showed that the U.S. flag is associated with egalitarianism and that exposure to the flag reduces hostile nationalistic attitudes toward Muslims and Arabs by increasing the influence of egalitarianism on these judgments. Addressing a similar process, Reference EhrlingerEhrlinger et al. (2011) discovered that exposure to the Confederate flag decreases positive attitudes toward Barack Obama. The authors suggest that this may be through the flag's activation of negative attitudes toward blacks (see also Reference Hutchings, Walton and BenjaminHutchings, Walton, and Benjamin 2010 on public reactions in Georgia to Confederate symbols). Similarly, Reference HassinHassin et al. (2007) found that exposure to the Israeli flag has the effect of moving Israeli subjects to the political center on a variety of political issues and on actual voting behavior, possibly by having activated the value of political unity. In transitional justice research, attention to the importance of symbols is also commonplace (e.g., Reference NoblesNobles 2008). Reference Weisbuch-RemingtonWeisbuch-Remington et al. (2005) take this line of research a step further by presenting symbolic stimuli that cannot be consciously perceived (because they are presented too briefly), and by then demonstrating a physiological impact of the symbols. The common component of this line of research is that it suggests that political symbols affect attitudes by changing the types of considerations people use to come to their final political judgments. That is the central hypothesis of our research.

Factors Conditioning the Effect of Judicial Symbols

We further hypothesize heterogeneous treatment effects: that judicial symbols do not influence everyone equally. In particular, we expect to see conditional effects of three factors.

Not everyone requires exposure to judicial symbols to activate thoughts related to judicial legitimacy. In particular, for those with repeated prior exposure to the pairing of the Supreme Court and judicial symbols, concepts and ideas that are strongly associated with judicial symbols may become closely connected to Supreme Court attitudes (and may do so spontaneously). When these various associations with the Supreme Court become strong enough, the contemporaneous exposure to judicial symbols may no longer be necessary because the meanings associated with judicial symbols are already well integrated into preexisting attitudes and associations with the Court. Legitimacy-based considerations and institutional feelings enter working memory spontaneously and effortlessly. This process suggests that those people most familiar with the Court will most likely experience the automatic activation of legitimacy considerations, irrespective of whether symbols are involved.Footnote 9 For these people, exposure to judicial symbols is redundant and not necessary for the activation of thoughts about institutional legitimacy. Hence, we hypothesize that:

H 1: The effect of the symbols is conditional upon the degree to which one is exposed to and aware of the Supreme Court. Specifically, judicial symbols are only likely to have an effect on those without extensive prior exposure to the Supreme Court.

Judicial symbols may not change attitudes; instead, we speculate that they influence the set of considerations loaded into working memory. Thus, the effect of symbols is hypothesized to be related to the nature of preexisting attitudes toward law, courts, and justice. Indeed, for those for whom law represents something to be feared, not revered, judicial symbols may activate negative institutional affect and thoughts of social control, unfairness, and repression, and consequently the symbols may motivate these individuals to resist a Court decision, rather than accept it. Obviously, we would not expect that the effects of the symbols of judicial authority are the same for those questioning the legitimacy of the Supreme Court and those extending great legitimacy to the institution. Specifically, we predict that:

H 2: The effect of judicial symbols is conditional upon the content of preexisting legitimacy attitudes. Specifically, symbols activate and empower existing institutional support; where support is high, acquiescence is expected to be likely. But where preexisting support is low, acquiescence is expected to be unlikely.

Finally, we return again to our claim that legitimacy is for losers. As will become clear below, our experiment exposes all respondents to a Supreme Court decision with which they disagree on an issue about which they care. For some, however, this contrary ruling is entirely expected—to these folks, the Court seems to routinely decide cases in the “wrong” direction. For others, the ruling runs contrary to what they presume the Court would do—because the Court seems to nearly always decide cases in the “right” direction. So despite the fact that every respondent is learning about a contrary decision in our experiment, the degree to which the decision violates the respondent's standing expectations varies, and therefore disappointment with the Court also varies. We hypothesize that for those not exposed to the judicial symbols, this disappointment translates quite readily into resistance to the Court's decision. But when the symbols of judicial authority are present, Positivity Theory predicts that thoughts about legitimacy are more readily accessible and therefore that the effect of disappointment in the decision on acquiescence will be mitigated. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H 3: The effect of the symbols is conditional upon the degree to which one is disappointed with the Court's ruling. Specifically, the presence of judicial symbols impedes the translation of disappointment into unwillingness to accept an unwanted Court decision.

Research Design

The Survey

This research is based on a survey conducted for us under a grant from Time-sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences. The sample—with the requirement that the respondents be American born—is drawn from Knowledge Network's (KN) “KnowledgePanel.”Footnote 10 Details on the survey, including the response rate, are reported in Appendix S1.

KN panelists respond to questionnaires made available to them via the internet. Consequently, we had limited control over the administration of the questionnaire. For our survey experiment, one of these factors is crucial: the length of the interview. The duration from beginning the survey to completion averaged 246 minutes, with a median of 12 minutes, with a range of 4–12,460 minutes. Obviously, some respondents completed the interview in more than a single session, which is important because some respondents may have been answering the “dependent variable” questions several days after exposure to the experimental manipulations. To control for this, we have confined the analysis to the 85 percent of the sample completing the interview in 30 minutes or less.Footnote 11

The Survey Experiment

In order to provide a realistic test of the acquiescence hypothesis, we focused the experiment on a substantive issue of some importance to the respondents. We did so by asking them to select from three possibilities the issue they considered “to be the MOST important—that is, the most important issue to you.” The choices were: (1) whether the government should be allowed to monitor citizens' searches on the internet, without a warrant from a judge; (2) whether the state governments should be allowed to require consumers to pay sales tax on items they buy on the internet; and (3) the issue of whether children of foreigners and illegal immigrants who just happen to be born in the United States should be automatically given American citizenship. Thus, this is a classic “content-controlled” measurement approach (see Reference Sullivan, Piereson and MarcusSullivan, Piereson, and Marcus 1982): All respondents are confronted with an issue of some importance to them, even if it is not the same issue.Footnote 12

After the respondents selected an issue, we measured their substantive preferences. Among those identifying government searches as most important, a large majority (81 percent) opposed the searches. For the tax issue, 75 percent opposed taxation, and for the immigration issue, 70 percent would not allow citizenship. In the analysis below, we control for the intensity of the respondent's position on the issue selected: 41 percent of the respondents indicated that their positions on their issues were strongly held. The three issues do not differ according to the intensity of the respondents' positions.

Our acquiescence experiment presented all respondents with a Supreme Court decision contrary to their preferred position. They were then asked whether they would accept the ruling with which they disagreed. That the experiment is based on all respondents being exposed to a Court decision with which they disagree on an issue important to them may limit the generalizability of our findings (i.e., our experiment does not address unimportant issues from the viewpoint of the respondent). At the same time, it increases our study's political relevance. Moreover, if “legitimacy is for losers,” then this is a quite appropriate, indeed essential, research design.

The Dependent Variable

Following earlier research (e.g., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and SpenceGibson, Caldeira, and Spence 2005; Reference Nicholson and HansfordNicholson and Hansford 2014), we conceptualize the dependent variable as the willingness or unwillingness to acquiesce to the Court's decision—that is, acceptance of the decision and unwillingness to join in efforts to punish the justices and the Court for its decisions. Unwillingness to accept Court decisions has peaked at several points in the Court's history, as in President Franklin D. Roosevelt's attempt to pack the Court in response to its rulings on New Deal legislation, the “Impeach Earl Warren” signs found throughout parts of the country in response to Brown v. Board of Education, the New York Times advertisement placed by nearly 600 law professors after the Court's Bush v. Gore ruling, and the attacks on the Court by various Republican aspirants during the 2012 presidential primary races. Legitimacy Theory posits that legitimate institutions will be “put up with” even when they make decisions that citizens oppose.

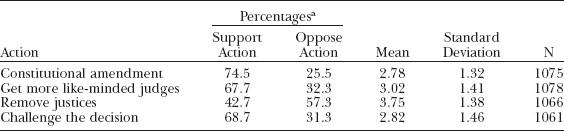

As the items reported in Table 1 make plain, these respondents assert considerable resistance to the Supreme Court's decision. About three-fourths would support a constitutional amendment to overturn the decision. Roughly two-thirds believe the decision ought to be challenged (not accepted) and that efforts ought to be made to get more like-minded judges on the Court. Only on whether the justices voting against the respondent's preference ought to be removed is there a majority willing to accept the decision. Generally, resistance to a disfavored court decision is commonplace among these survey respondents.Footnote 13

Table 1. Acquiescence to a Disagreeable Supreme Court Decision

a These two percentages total to 100%, except for rounding errors.

Higher mean scores indicate greater willingness to acquiesce to the Court decision. The range of these scores is from 1 to 5.

The survey questions read:

Now we would like to get your reaction to the U.S. Supreme Court's decision on this issue.

Because of this decision, would you support or oppose efforts to overturn this decision with a constitutional amendment?

Strongly support Somewhat support Oppose Support Somewhat oppose Strongly oppose

Because of this decision, would you support or oppose efforts to get more judges on the Supreme Court who agree with you that [R'S PREFERENCE ON HIS/HER SELECTED ISSUE]?

Strongly support Somewhat support Oppose Support Somewhat oppose Strongly oppose

Because of this decision, would you support or oppose efforts to remove justices who voted the wrong way on this case?

Strongly support Somewhat support Oppose Support Somewhat oppose Strongly oppose

Do you accept the decision made by the court? That is, do you think that the decision ought to be accepted and considered to be the final word on the matter or that there ought to be an effort to challenge the decision and get it changed?

Strongly believe the decision ought to be accepted and considered the final word on the matter?

Somewhat believe the decision ought to be accepted and considered the final word on the matter?

Somewhat believe there ought to be an effort to challenge the decision and get it changed?

Strongly believe there ought to be an effort to challenge the decision and get it changed?

We created an acquiescence index from the responses to these four items. The item set is strongly unidimensional (the eigenvalue of the second factor extracted via common factor analysis is only 0.85), although only weakly reliable (Cronbach's alpha = 0.64; mean interitem correlation = 0.31). That the correlations are not stronger is probably a function of the fact that these are categorical variables. Our index of acceptance is simply the summated score of the four items; this index is correlated with the factor score from the common factor analysis at 0.99.

The Experimental Manipulation

This experiment involves a simple 2 × 2 manipulation based on two dichotomies (with independent random assignment to each condition): (1) judicial versus abstract symbols present on the computer screen, and (2) a legal commentator's criticism of the Court's decision as not grounded in legal principles versus no commentary. In this analysis, we focus only on the effects of being exposed to the symbols of judicial authority.Footnote 14 Doing so produces no specification error because that variable is orthogonal to the rest.Footnote 15

After the respondents declared their positions on the issue of importance to them, we presented a headline on the screen that read: “The U.S. Supreme Court decides an important case on [INSERT TEXT ON R'S ISSUE].” At that point, the direction of the decision was not revealed. The screen proclaiming the ruling was rimmed with either judicial or abstract symbols (with random assignment to condition).Footnote 16 As shown in Figure 1, in the symbols condition, a picture of a gavel was shown at the top left of the screen, the Supreme Court building on the top right, and a picture of the nine robed justices at the bottom of the screen. For the control condition (the abstract-symbols condition), rough analogs were presented, with the symbols mimicking the judicial symbols in shape and form but having no substantive content.Footnote 17

Figure 1. The Symbols Manipulation: Judicial Versus Abstract Symbols.

Before revealing the Court's decision to the respondent, we measured the generalized affect toward the Court (see below). The next screen then announced the decision, which in every instance was contrary to the respondent's preference. During the announcement of the ruling, the symbols (judicial or abstract) remained in place on the screen.

As indicated by our hypotheses, we anticipate that the strongest consequences of symbols for acquiescence are conditional. We must therefore introduce several additional variables related to the preexisting attributes of the respondents to the analysis.

Institutional Support for the U.S. Supreme Court

The simplest and most well-established hypothesis we consider states that acquiescence is a direct function of institutional support for the Supreme Court. We measured support for the Court at the beginning of the survey, well prior to presenting the respondents with the experiment,Footnote 18 followed by a significant battery of distractor questions. As expected, institutional support is fairly strongly related to acquiescence (r = 0.42) and is completely orthogonal to the experimental manipulations.

Exposure to the Supreme Court

We measured exposure with a single item: “How often do you read or hear news about the U.S. Supreme Court? Very often, often, somewhat often, not very often, almost never or never?” Like most Americans, our respondents were not particularly attentive to the Court, with a modal answer of “not very often” (39 percent) and with only 32 percent reporting having read or heard news about the Court at least “somewhat often.” Confirming a long line of research (e.g., Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson and Caldeira 2009), those reporting greater exposure express more support for the Court: r = 0.19. Exposure is, however, independent of acquiescence to the unwanted decision. The variable we use in our analysis is a dichotomization of the measure of attentiveness, which we split into those who read or heard about the Supreme Court at least “somewhat often” (32 percent of the sample) versus those who read or heard about the Supreme Court “not very often” or less frequently (68 percent of the sample).Footnote 19

Decisional Disappointment

Our measure of decisional disappointment is created from the feeling thermometer question asked immediately prior to the decision being announced. We posit that those feeling more favorable toward the Court are more disappointed with an important decision that runs directly counter to their preferences. Some comments on this measure are necessary.Footnote 20

In an investigation of measures of specific and diffuse support, Gibson, Caldeira, and Spence (Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Spence2003b) concluded that a feeling thermometer measure is more strongly influenced by specific support than by diffuse support. Consequently, when a thermometer is included in a multivariate equation that also includes a direct measure of institutional support as a control variable, the direct influence of the feeling thermometer is even more likely to be something akin to specific support—the belief that the institution is performing well in deciding cases. Treating this belief as a generalized expectation that the Court will decide cases “correctly” (i.e., consonant with the individual's preferences), and juxtaposing that expectation against the announcement of an important Court decision contrary to the preferences of the respondent, we have a measure of disappointment. In short: (1) those feeling warmly toward the Court are likely to expect the Court to decide cases “correctly,” (2) when the Court does not decide an important case “correctly,” disappointment results, and (3) therefore, the continuum from cold to warm can be treated as a variable ranging from low to high disappointment with the decision announced to the respondent—especially in an analysis that includes a direct measure of institutional support in the equation.

Analysis

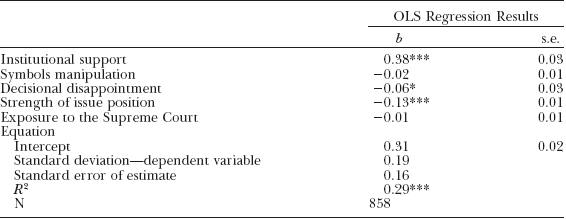

Table 2 reports a simple analysis of the variance in acceptance using five independent variables: institutional support, experimental exposure to the symbols, the strength of the respondent's issue position, decisional disappointment, and prior exposure to the Supreme Court via the news.Footnote 21 These five variables account for more than one-fourth of the variance in willingness to accept an unwelcomed Court decision.

Table 2. The Predictors of Acquiescence to an Unwelcomed Supreme Court Decision

Significance of regression coefficients: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Note: All variables are scored to range from 0 to 1. b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error of unstandardized regression coefficient; R 2 = coefficient of determination.

As expected, institutional support is a strong predictor of acquiescence, as is the strength of one's issue position (stronger opinions are associated with less acquiescence). The other two observational variables, however, have little direct influence on acquiescence. Those with greater prior awareness of the Court are no more likely to acquiesce than those with relatively less awareness. Nor does decisional disappointment have much of a direct effect on acquiescence.

Not unexpectedly given the findings of pilot studies, exposure to the symbols is completely unrelated to willingness to accepting the decision. However, there is more to the story of the influence of symbols. The overriding hypothesis of this research is that exposure to the symbols interacts with other variables in the model. Thus, additional analysis is necessary.

Testing Interactive Hypotheses

Following the earlier research findings of Reference Woodson, Gibson and LodgeWoodson, Gibson, and Lodge (2011),Footnote 22 we hypothesize a three-way interaction involving prior exposure to the Court, institutional support, and the experimental exposure to the symbols of judicial authority. Specifically, we hypothesize that symbols serve as a nonverbal method of attitude activation. This process is likely to be influential among those with low prior exposure to the Court but not necessarily among those with relatively high exposure, among whom these considerations are fully activated by words alone (see Reference KamKam 2005). Those most familiar with the Court are assumed to have formed the connection between legitimacy and acquiescence quickly and perhaps even automatically, and therefore no additional priming by the symbols is necessary to activate, connect, and empower the attitudes. Among those with less prior exposure, however, the reasons why one might acquiesce to a decision with which one disagrees may not be immediately accessible; therefore, being exposed to the symbols may be necessary for legitimacy attitudes to be fully accessible in working memory. Finally, this process concerns legitimacy attitudes, but of course not all respondents extend legitimacy to the Court (see below), so variability in legitimacy must form part of the three-way interaction.

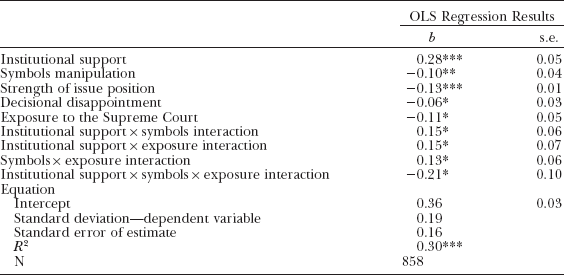

Table 3 reports the results of the hypothesized three-way interactions, including, of course, the two-way interaction terms of the constituent variables. The first thing to note about this analysis is that, in a hierarchical model,Footnote 23 the addition of the two-way interactions to the basic equation does not produce a statistically significant change in R 2; however, adding the three-way term to the two-way equation does. The null hypothesis that all of the relationships of these variables with acquiescence are linear (i.e., not conditional) can be rejected.

Table 3. The Predictors of Acquiescence to an Unwelcomed Supreme Court Decision—The Interaction of Prior Court Exposure, Institutional Support, and Exposure to Symbols

Significance of regression coefficients: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Significance of the change in R 2, adding two-way interactions: not significant.

Significance of the change in R 2, adding three-way interaction: p < 0.05.

Note: All variables are scored to range from 0 to 1. b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error of unstandardized regression coefficient; R 2 = coefficient of determination.

The most important finding of this table has to do with the interaction of institutional legitimacy with exposure to the judicial symbols (H2). Note first that those high in prior exposure to the Court were entirely unaffected by being exposed to the symbols—the regression coefficient for those shown the abstract symbols is 0.43; for those shown the judicial symbols, the coefficient is 0.37, which is not significantly different.

But the same is not true of the other two-thirds of the sample. We first observe that the direct effect of legitimacy on acquiescence is significant even under the most limiting condition: among those with relatively low prior exposure to the Supreme Court and who were not shown the symbols of judicial authority (b = 0.28, p < 0.001). At the same time, however, among those with low prior exposure to the Court, being exposed to the symbols significantly increased the connection between institutional support and acquiescence. In the absence of symbols, the regression coefficient is 0.28; among those shown the judicial symbols, the coefficient is 0.43 (0.28 + 0.15), which is significantly different from 0.28 (at p < 0.05). Thus, among those with low previous exposure to the Supreme Court, the effect of being exposed to the symbols is to raise the influence of legitimacy on acquiescence to the same level observed among those with relatively high prior awareness: 0.43 in both instances. The effect of being exposed to the symbols is therefore equivalent to the effect of regularly hearing and reading about the Supreme Court. Footnote 24

It is useful to explore this important relationship further. Our theory holds that symbols activate preexisting connections between thoughts about the judiciary and thoughts about fairness and legitimacy. This then leads to the hypothesis that the effect of symbols differs according to preexisting levels of institutional support. If support for the Supreme Court is low, then the symbols might actually activate negative thoughts about the judiciary, which also suggests an interaction between exposure to the symbols and levels of institutional support. The significant interaction between institutional support and exposure to judicial symbols shown in Table 3 supports this hypothesis.

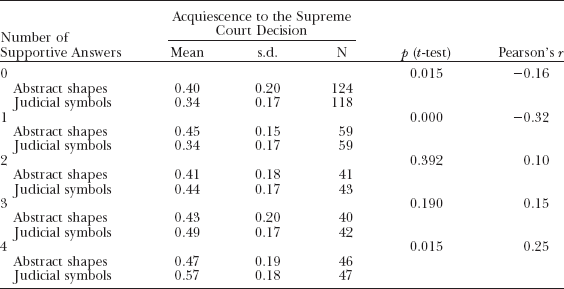

To more clearly illustrate this relationship, we have examined the effect of symbols exposure at various levels of institutional support. Table 4 reports the differences in means in acquiescence according to whether the respondents were exposed to the judicial symbols or the abstract shapes at differing levels of institutional support (within the two-thirds of the sample with relatively low prior awareness of the Supreme Court—recall that the symbols have little effect on those with high levels of prior awareness of the Court). As a simple measure of level of support, we use the number of supportive replies the respondent gave to our four institutional support items. The table reports the significance of a t-test on the difference in the mean acquiescence index scores across the two symbols conditions, as well as a measure of association between the symbols manipulation and the index.Footnote 25

Table 4. The Effect of Exposure to Judicial Symbols at Varying Levels of Institutional Support (Low Supreme Court Awareness)

These data reveal that the effect of the judicial symbols varies considerably according to the respondent's level of preexisting support for the Court. Among those relatively less supportive of the Court, the symbols depress the propensity to acquiesce; among the more supportive, the symbols have the expected effect of increasing acquiescence. The progression of the correlation coefficients is revealing. At the two lowest levels of support, fairly substantial negative relationships exist. Among those giving two or more positive replies to the support items, the relationship between the symbols and acquiescence strengthens as support for the Court grows. To reiterate, throughout the entire range of institutional support, a unit increase in support is associated with a greater likelihood of acquiescence, and this slope is larger for those exposed to the symbols. But within levels of institutional support, exposure to the symbols is associated with a variable effect on acquiescence, sometimes positive, sometimes negative.Footnote 26 The symbols seem to activate and empower preexisting attitudes—whatever they may be, positive or negative.

The Disappointment Hypothesis

The symbols of judicial authority are hypothesized to activate a range of legitimacy considerations, thoughts that when juxtaposed against disappointment with the Court's policy decision block the natural connection between disappointment and willingness to challenge the decision. We must therefore test another interactive relationship.

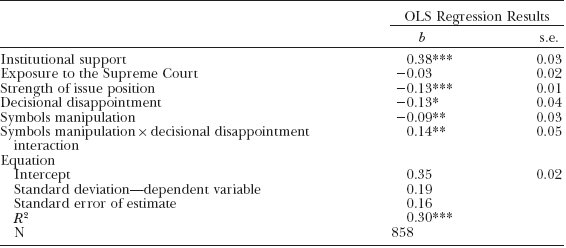

Table 5 reports the results of an analysis of the interaction between exposure to the symbols of judicial authority and disappointment in the Court's decision. To the basic equation we reported in Table 2, we add a term for the interaction between the experimental condition and decisional disappointment.Footnote 27

Table 5. The Interaction of Symbols and Decisional Disappointment as Predictors of Acquiescence to an Unwelcomed Supreme Court Decision

Significance of regression coefficients: ***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05.

Note: All variables are scored to range from 0 to 1. b = unstandardized regression coefficient; s.e. = standard error of unstandardized regression coefficient; R 2 = coefficient of determination.

The analysis reveals that exposure to the judicial symbols significantly conditions the impact of disappointment. With exposure to only the abstract symbols, the effect of decisional disappointment is significantly negative: −0.13. However, for those respondents who were shown the judicial symbols, the coefficient is 0.01 (−0.13 + 0.14 = 0.01), which is obviously statistically indistinguishable from 0, but which is also significantly different from −0.13. In the absence of judicial symbols, disappointment translates into resistance to the Court's decision, with those more disappointed being less likely to accept it. In the presence of judicial symbols, disappointment is overridden, eliminating its consequences for resistance.Footnote 28

Discussion and Concluding Comments

This analysis has produced three important findings. First, not everyone requires exposure to judicial symbols to activate a complete set of considerations about judicial legitimacy. For those most aware of and supportive of the institution, mere mention of the “Supreme Court” seems to mobilize myriad legitimacy-enhancing thoughts. For the more numerous less-aware Americans, exposure to judicial symbols is required to invigorate legitimacy attitudes, perhaps by associating a broader set of dormant considerations related to legitimacy. Indeed, we find that the effect of legitimacy on acquiescence is nearly identical for two subsets of respondents: all high-information respondents and low-information respondents who have been exposed to the symbols of judicial authority. The similarity of this effect is striking.

Second, the effect of judicial symbols interacts with one's level of preexisting institutional support. For those respondents low in support in the first place, the symbols increase resistance to the Court's decision. Only among those expressing relatively high institutional support do we find that symbols accelerate the influence of support on acquiescence. We take these results to mean that judicial symbols activate available but not readily accessible considerations in the individual's long-term memory. But individuals differ in how they feel about law, with some viewing law, courts, and judicial authority as helpful and benign, but others viewing law as threatening and malevolent. Exposure to judicial symbols does not change individuals—instead, it seems to change the mix of considerations available in working memory when people are called upon to make a decision.

Third, one impact of the symbols of judicial authority seems to be through impeding the transformation of disappointment in a Court decision into willingness to challenge that decision. Our empirical analysis shows that when judicial symbols are present, the effect of policy disappointment on acquiescence is reduced to zero. We suggest that this blocking function is a result of additional considerations related to the fairness of judicial decisionmaking being activated by the symbols.

We are not certain about the exact psychological processes that underlie our findings. Still, assume for the moment that prior awareness of the Court is correlated with greater understanding of the role of the judiciary in a democratic society. Among those with less understanding, the immediate reaction to an adverse judicial decision is to want to challenge the decision, the judges who made the decision, and perhaps even the institution itself. For these respondents, we hypothesize that the initial reaction to the unfavorable court decision is akin to the reaction to an unfavorable decision by a legislature. These citizens do not like the outcome and want to do something about it.

But for those with a greater understanding of democratic institutions and processes, this initial impulse to challenge the decision is immediately countered by an additional set of considerations. Those considerations counsel forbearance, perhaps under the theory that the judiciary is different from the legislature, that the judiciary ought to be respected because its decision-making processes are principled, not strategic, and that the role of the judiciary is, on occasion, to tame the passions of the majority. These citizens do not like the outcome, but cede the right of the courts to make such decisions and recognize that citizens must occasionally acquiesce to court rulings with which they disagree.

A third set of citizens supports the Court but has a more limited understanding of the judiciary and therefore does not immediately arrive at a decision to accept its ruling. These citizens need some impetus to move beyond the initial impulse to challenge a bad decision because their attitudes are less crystallized and their interattitudinal associations are more tenuous. The symbols in essence stimulate these citizens to give the matter “a sober second thought” (e.g., Reference GibsonGibson 1998)—they activate a set of legitimating thoughts and feelings, perhaps not especially well organized, that run counter to the initial impulse to challenge the court's decision.

We readily acknowledge that we do not have direct evidence of how these respondents understood the symbols (such as judicial robes) we presented to them. We imagine, however, that the symbols conveyed some information suggesting a distinctive process of governmental policymaking, a process worthy of respect. For some respondents, the process may therefore have gone as follows: (1) Disappointment is created by the contrary Court decision. (2) The judicial symbols activate fairness considerations. (3) In thinking about why and how the Court made its decision, the effect of the disappointment is tempered by the belief that either the decision was principled and impartial, or that it was commanded through some sort of mechanical jurisprudence process. (4) Because the decision was made in a fair way, the thought that it ought to be accepted occurs. Contrariwise, those exposed to abstract symbols were less likely to have considerations of fairness readily available, and therefore nothing was in working memory to impede the translation of disappointment into resistance. The judicial symbols seemed to activate an additional set of considerations that were able to serve as counterarguments as to why disappointment with the decision should not lead to resistance to it. And as we have noted, our empirical analysis demonstrates that the effect of the symbols is to render these citizens similar to the more sophisticated and informed one-third of our sample. This, we argue, is a formidable result.

Finally, a fourth set of citizens extends relatively low support to the Court, and exposure to the symbols of judicial authority seems to activate and exacerbate their legal alienation. For these citizens, law may be viewed as a repressive rather than liberating force. As Reference Gibson and CaldeiraGibson and Caldeira (1996: 60–61) observed using ordinary survey data:

For some [people], law is no doubt thought of as a rather neutral force, perhaps embodying consensually held social values. Those who view law in this way are likely to value it as a liberating force, either because it creates or reinforces a desirable social order or because it serves other interests of the entire citizenry. … Others, however, may perceive law as an external, repressive, and coercive force … as a means by which others advance their contrary political interests. … This view of law as an instrument of political struggle, of political conflict, stands in sharp contrast to the perception that law represents the consensual interests of society.

Gibson and Caldeira find substantial cross-national variability in these attitudes (which they term “legal alienation”). It may very well be that our experimental data are revealing this same sort of legal alienation, with a substantial portion of the American people associating legal symbols with negative feelings toward legal authority and institutions.

Our sample is comprised of native-born respondents so we cannot speak to how our results generalize to the full American population. About 13 percent of the U.S. population was born outside the United States—our data are silent as to how people born and raised in other countries feel about law and legal symbols. We do know, however, that for a sizable portion of our American-born sample (as shown in Table 4 above), the judicial symbols actually stimulate resistance to an objectionable Supreme Court decision. Whether the symbols of judicial authority have a net-positive or net-negative effect on Supreme Court legitimacy is therefore dependent upon the distribution of preexisting attitudes in the population. Symbols do not change attitudes; instead, they seem only to activate attitudes that already exist. In some contexts, the symbols of judicial authority may well serve to delegitimize rather than legitimize courts.

Legal scholars have long speculated that the judiciary profits from the availability of widely understood symbols of judicial authority. To date, however, no systematic empirical evidence has documented such an influence. Our analysis has the advantage of using a representative sample of native-born American people and we therefore have some confidence in the external validity of our findings. Since we employed an experimental research design, we also have some confidence in our finding's internal validity.

However, we must acknowledge three crucial limitations to this project. First, some of our most important findings rely on relationships grounded in observational, not experimental, data, and a key variable in our analysis (disappointment) behaved in a fashion contrary to our original expectations. Second, our findings are somewhat complicated, reflecting the fact that the influence of symbols interacts with the context within which the symbols are presented. Finally, our research is shallow when it comes to documenting the mechanisms about which we speculate, and we readily acknowledge that we have insufficient direct evidence on the processes we have outlined. Our findings are compatible with symbols influencing spontaneously activated dormant beliefs and attitudes, but we have no direct evidence that our speculation is correct.Footnote 29

More generally, all research based on experimental research designs—even that grounded in representative samples—faces some important limitations of external validity. In nature, people are exposed to information about the Supreme Court and its rulings within far less rarified contexts, as compared to the experimental setup. News about the Court may be accompanied by a crying child, food that needs preparing, phones that are ringing, and other distractions. The effect in the lab is almost always the maximum possible effect one might observe; the effect in reality is almost always much smaller than the maximum.Footnote 30 And perhaps more importantly, experimentalists can never be at all certain that the effects they observe and/or create in the lab persist. In our case, we contend that symbols contribute to acquiescence, but of course we have not modeled the myriad additional factors—such as appeals from anti-Court elites—that may run strongly counter to the effects of symbols. Experiments focus on discrete events; in real politics, events unfold, interacting with one another, over a period of time. All recognize the strengths of experimental designs. It is important as well to recognize fully their limitations.

At least three additional research questions require further empirical consideration. First, we have suggested that without the presence of judicial symbols, those with little prior exposure to courts do not differentiate much between judicial and other political institutions. That hypothesis is amenable to empirical investigation. Second, we have hypothesized that among political sophisticates, the activation of legitimacy attitudes is virtually automatic—a System 1 process whereby thoughts and feelings come effortlessly to mind to inform a judgment—while for less sophisticated citizens, the availability and accessibility of considerations in a judgment is characterized by the slow, cognitively demanding, piecemeal integration of thoughts and feelings typical of System 2 decisionmaking (Reference KahnemanKahneman 2012; Reference Lodge and TaberLodge and Taber 2013). These and other hypotheses regarding System 1 and System 2 processes certainly require and deserve additional empirical consideration if we are to understand fully the ways in which symbols influence the political attitudes and behaviors of citizens, and thereby sustain the legitimacy of American political institutions. Finally, future research should attempt to determine whether there is anything unique about judicial symbols, especially when compared to the symbols of other authoritative political institutions (e.g., the legislature, as represented in the Capitol building). We deliberately chose as our control group a set of abstract symbols. Now that we have shown that exposure to judicial symbols influences how citizens react to the Court, a useful and necessary next step is to hone in on exactly how symbols are understood and how different symbols are similar and/or different. It appears that symbols are important for law and politics; future research should focus on understanding exactly how and why.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Appendix S1. Survey details.

Appendix S2. The measurement of institutional support.

Appendix S3. Marginal effects.