INTRODUCTION

The vast majority of authoritarian regimes, like their democratic counterparts, have constitutions, and, in civil law systems, most also have constitutional courts that rule on legal matters related to those constitutions. However, scholars generally expect that, under a dictatorship, neither these courts nor the documents they are charged with upholding constrain the ruler’s authority. Rather than challenging constitutional provisions that grant the president expanded authority, constitutional courts simply certify the underlying balance of power and rule in favor of the president.Footnote 1 At first glance, Kazakhstan, a former Soviet republic in Central Asia, reflects this characterization. President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s nearly thirty years of rule has seen a series of constitutional changes and subsequent court decisions that certified in de jure form his personal consolidation of power in the first decade after the Soviet collapse. Amendments such as those naming him “first president” and “leader of the nation” expanded his formal powers, gave him immunity from future prosecution, and guaranteed him a lifetime role in the country’s politics, including as a permanent member of the Constitutional Council of the Republic of Kazakhstan (CCRK) (formerly, the Constitutional Court)Footnote 2 and as the chairman for life of the powerful Security Council. These formal provisions have facilitated his continued de facto political control after transferring the presidency to a chosen successor in 2019. In short, the CCRK today reflects prevailing expectations regarding courts under authoritarianism.

If constitutional courts simply reflect the underlying distribution of political power, their acquiescence to the dictator’s legal reforms should be guaranteed. Certainly, this description applies to “established” authoritarian regimes where rulers have already succeeded in eliminating any credible opposition (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). However, dictators rarely begin their rule in this manner; in the immediate wake of regime change, the ultimate distribution of political power often remains uncertain and fiercely contested. Indeed, when Kazakhstan suddenly became independent in 1991, the Supreme Soviet—a “rubber stamp” body under Soviet rule— challenged him vociferously over his attempts to consolidate power in his own hands. Because political competition in such nascent authoritarian regimes occurs simultaneously within and over the “rules of the game,” the courts responsible for adjudicating the highest level of those rules become an essential chess piece in this nested contest (Schedler Reference Schedler2002, 110). If they control the institution that sets those formal rules, aspiring dictators like Nazarbayev are able to dominate the overarching narrative of what constitutes the “law.” This in turn helps legitimize their efforts to transform nominally democratic institutions like legislatures, elections, and political parties into instruments that limit, rather than foster, political competition. In other words, they are able to leverage the institution’s normative status to shape national political discourse and values (Ginsburg and Simpser Reference Ginsburg and Alberto2014) as well as expectations over how power will be distributed through formal institutions (Hale Reference Hale2011).Footnote 3 Conversely, failure to secure tight control over the constitutional court risks leaving an opening for opponents to use the court to shift that playing field in their favor.

How, then, do aspiring dictators succeed in capturing this critical institution, particularly when they still face fierce competition from other elites for political control? Answering this understudied question is critical for understanding the larger processes of institutional change that unfold after a country experiences regime change, especially when that change is sudden and unexpected, as was the Soviet collapse. Moreover, because contemporary autocrats have increasingly come to power through democratic elections and dismantled democracy from within via legal reforms (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018; Mainwaring and Bizzarro Reference Mainwaring and Fernando2019), a close examination of successful court capture has implications for our broader understanding of the current “accelerating wave of authoritarianism” that has resulted in over three-quarters of the world’s population living under non-democratic rule (Alizada et al. Reference Alizada, Rowan, Lisa, Sandra, Sebastian, Palina, Jean, Anna, Maerz, Shreeya and Lindberg2021, 9).

We draw on the Kazakhstani case to argue that, during periods of initial regime consolidation, high levels of uncertainty make capturing top courts an attractive strategy for ensuring dictators’ control over ever-shifting legal rules and for legitimizing their continued tenure in office. We then use a framework of interests, constraints, and opportunity to trace the process of constitutional court capture in Kazakhstan. Though aspiring dictators are interested in securing control over constitutional courts to ensure that they have a strong handle on shaping the legal playing field, they may face constraints on their ability to do so. In the Kazakhstani case, these constraints have included a combination of international norms and expectations surrounding judicial independence and resistance from domestic elites who have opposed any expansion of the autocrat’s individual political power. Given such constraints, leaders like Nazarbayev will therefore wait for an opening—in the case of Kazakhstan, this was (ironically) a Constitutional Court ruling—to institute formal reforms that facilitate their capture of the court at a lower political cost. Once captured, dictators can then rely on the court to legitimate legal changes that contribute to the further consolidation of political power in their own hands.

In taking this approach, we bridge prior research on the politics of constitutional courts with the literature on the use of nominally democratic institutions as tools of autocratic governance. More specifically, we link the court’s institutional design in the face of global and domestic constraints with political tactics that apply a veneer of legitimacy to “soft” repression. This use of constitutional courts to quash political contestation and support authoritarian consolidation echoes other scholars who have found that law and courts in non-democracies are key components of autocrats’ “tool kits” for addressing mass and elite threats. For example, Jothie Rajah (Reference Rajah2012) shows how the regime in Singapore strategically leveraged criminal law and courts to stifle emerging popular movements without highly visible brute force; on the elite side, Michael Albertus and Victor Menaldo (Reference Albertus and Victor2012, Reference Albertus, Victor, Ginsburg and Simpser2014) find that constitutions have played a central role in defining and consolidating power within ruling coalitions in a wide range of autocracies.

This article also joins a line of inquiries that seriously consider the role of courts in post-Soviet authoritarian regimes (for example, Herron and Randazzo Reference Herron and Randazzo2003; Trochev Reference Trochev2004, Reference Trochev2011; Hendley Reference Hendley2009; Mazmanyan Reference Mazmanyan2010, Reference Mazmanyan2015; Epperly Reference Epperly2012; Wilson Reference Wilson2012; Trochev and Solomon Reference Trochev and Solomon2018). Like Alexei Trochev (Reference Trochev2004), we suggest that the choice to use constitutional courts in this context is closely tied to projecting legitimacy, understood broadly as the recognized right to rule. In newly formed states with an uncertain regime-type future, the design of constitutional courts, within the scope of international norms, and how that design interacts with the pressure put on those courts once they are in place, can serve as a means of consolidating tenure in office while maintaining a stance that those actions are legitimate (however questionable its legal logic may be). In an era where—at least rhetorically—even autocrats subscribe to democratic institutions and rule of law, leveraging courts’ authority over law in this way provides a potent tool for justifying institutional reforms that further concentrate dictators’ political power.

The remainder of this article begins with a discussion of the prior literature on constitutionalism and constitutional courts. We then situate these concepts within broader discussions of the role of courts and other nominally democratic institutions in different regime types. We outline our general framework for making sense of the process of capture before turning to the specifics of constitutional court transformation and continued control in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Our analysis continues with an in-depth look at specific cases that have provided legal support for Nazarbayev’s continued tenure as president, drawing on an original database of the CCRK’s decisions from its inception through 2015. Finally, we offer conclusions and implications for understanding the dynamics of constitutions and courts under the conditions of uncertainty that accompany regime change.

GLOBAL “DEMOCRATIC” CONSTITUTIONALISM

The backdrop to our argument is a global environment of constitutionalism and constitutional review. In the modern era, a constitution is a fundamental element in the making of a state. Because the document and the “will of the people” that it represents are treated as the highest form of law, it is closely associated with the construction of Weberian rational-bureaucratic legitimacy. Legitimacy broadly speaking refers to “the beliefs that bolster willing obedience,” which makes citizen compliance with the state easier to obtain (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Audrey and Tom2009, 354). Rational-bureaucratic legitimacy refers specifically to authority derived from impersonal, formal rules (Weber Reference Weber1954), and these rules—especially those establishing checks on state authority and the independence of institutions tasked with upholding those limits, like the judiciary—are a key feature of modern constitutions. A system of law that lays claim to rational-bureaucratic legitimacy in theory provides a means for citizens to fairly adjudicate disputes; similarly, a constitution that formally establishes democratic institutions in theory provides a path for fair political contestation. Amartya Sen (Reference Sen1999) traces the rising importance of the latter directly to the collapse of the Soviet Union, when the range of globally acceptable models of governance suddenly shrank, and democracy became “hegemonic.” Most autocratic leaders therefore chose to claim democracy and include essential democratic institutions like elections, legislatures, parties, and independent judiciaries as well as rights such as free speech and assembly in their constitutions in the post-Soviet era, and Kazakhstan was no exception.

Largely overlooked in this focus on democratic institutions, however, is the extent to which rational-bureaucratic legitimacy in the law effectively became ideationally “hegemonic” alongside democracy. Just as today authoritarian regimes claim to be democracies and maintain the institutional trappings of a democratic system, so too do they characterize themselves as dedicated to a rational-bureaucratic approach to the rule of law. Even highly autocratic political leaders link their actions (at least rhetorically) to following the rules of the constitution and, more generally, upholding the mandates of law. Absent a legal rationale, however tortured, dictators must challenge the “default” setting by offering a compelling alternative, but few of those alternatives remain. Totalitarian states that rely on an all-encompassing ideology and refuse the essential idea that citizens have rights vis-à-vis the state are difficult to maintain in today’s hostile international environment and, as the rare cases of North Korea and Turkmenistan demonstrate, also tend to suffer economically and diplomatically on the world stage as a result.

It is far less costly to instead deploy constitutions and courts strategically, claiming adherence to widely resonant international norms while subverting them in practice. For example, when Nazarbayev resigned from the presidency in 2019 and handed the presidency to his chosen successor, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, he followed the legal procedures outlined in the constitution, even as the events surrounding his resignation and the subsequent elections demonstrated that Kazakhstan was and continues to be an authoritarian state where other parts of the constitution—such as those establishing freedom of association and speech—remain a facade.Footnote 4 The prima facie adherence to constitutional rules in this example highlights how dictators strategically and selectively act in accordance with law to legitimate their actions.

Closely linked to the process of constructing constitutionalism and the rule of law are decisions about how and by whom constitutional provisions should be clarified when disputes arise. According to data from the Comparative Constitutions Project, 83 percent of constitutions in 2011 contained provisions for judicial review over the constitution, a substantial increase from the 38 percent that contained such provisions in 1951 (Ginsburg and Versteeg Reference Ginsburg and Mila2013, 587). Post-Soviet states like Kazakhstan emerged into a world of rising judicial review and specialized review bodies, such as constitutional councils (Stone Sweet Reference Stone2000, 30; Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003; Hirschl Reference Hirschl2004; Horowitz Reference Horowitz2006; Ginsburg and Versteeg Reference Ginsburg and Mila2013).Footnote 5 Moreover, they did so at a time when they were trying to rejoin the international community and develop relationships to jump-start their economies in the wake of the Soviet collapse. This issue was particularly pressing for states in Central Asia and the Caucasus, which had largely served in a quasi-colonial role in the Soviet Union’s economy, providing raw materials for “export” to more industrialized regions for processing (Loring Reference Loring2014). As a result, they had a strong incentive to formally align their institutional reforms with dominant international models to gain access to foreign investment, international aid, and new export markets from outside the former Soviet Union. Consequently, while the origins of judicial supremacy and the means by which it has spread are subject to debate (Ginsburg and Versteeg Reference Ginsburg and Mila2013; Menaldo and Webb Williams Reference Menaldo, Nora, Melton and Hazell2015), by the time the post-Soviet states were designing their constitutions and mechanisms for constitutional review, many international factors in favor of judicial (or quasi-judicial) review were being combined. Put more simply, international expectations created a new norm that made including constitutional review the default, and least costly, option.

We note here that there is a distinction between constitutional courts and councils, though both serve the purpose of determining the constitutionality of laws and policies. Councils, originating in the French model, are generally more limited in terms of review powers than constitutional courts. The original French council was created “to guarantee the dominance of the executive (the government) over a weak parliament” by providing a means to nullify legislation prior to enactment and limiting which actors were allowed to initiate the review of legislation (prior to 1974, only the president, the president of the Assembly, and the president of the Senate could request a review) (Stone Sweet 2000, 41, 45–47). As the CCRK is a “council” by name, this raises some concern that it is not appropriate to treat the CCRK as a judicial body at all. And, yet, as the detailed discussion of the CCRK below demonstrates, it is not a council in its purest form. Instead, the CCRK is a hybrid between a council and a court. For example, it includes some means of post hoc review after legislation has been passed, and lower courts can bring questions to the council for consideration.Footnote 6 We therefore deem it appropriate to treat the council as a judicial, or at least quasi-judicial, body.Footnote 7

CAPTURING CONSTITUTIONAL REVIEW

The above conditions set the stage for post-communist countries like Kazakhstan to adopt constitutions and, with them, constitutional courts. However, their alignment with prevailing international norms did not guarantee that courts would become instruments of democratic governance or Weberian rational-bureaucratic rule; for that, judicial independence was crucial. Judicial independence means that the branch has significant “insulation from politics” (Helmke and Rosenbluth Reference Helmke and Frances2009, 384) and, in particular, independence from the wishes of the legislative and executive branches.Footnote 8 Judges can rule against the material interests of legislative, executive, and elite nongovernmental actors with relative impunity.Footnote 9 Without this independence, courts lack the ability to interpret the constitution in accordance with legal principles rather than political pressures. In those cases, the judiciary is often considered “captured,” or dependent, on other political actors—most frequently, the executive. Post-Soviet Kazakhstan fits this description well: on a scale from zero to one, V-Dem evaluated the judiciary’s ability to constrain the executive in 2015 as just 0.15, which is close to the minimum present in the data (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, John, Carl Henrik, Lindberg, Jan, David, Michael, Agnes Cornell, Lisa, Haakon, Adam, Allen, Anna, Maerz, Marquardt, Kelly, Valeriya, Pamela, Daniel, Johannes, Brigitte, Rachel, Svend-Erik, Jeffrey, Aksel, Eitan, Luca, Wang, Tore and Daniel2021); similarly, Freedom House rates the country’s judicial framework and independence close to one, which is its lowest-possible rating, due in large part to the executive’s de facto domination of the judicial system (Freedom House 2018). In short, the country represents a widely accepted case of executive capture, including of the CCRK.

This description comes despite the CCRK’s nominal independence. Nominal independence indicates that provisions protecting the independence of the judiciary are enshrined in the constitution or laws. For evidence of judicial independence (or lack thereof), it makes sense to look toward these formal rules; indeed, James Melton and Tom Ginsburg (Reference Melton and Tom2014) found that independence clauses for court appointments were the best predictors of de facto judicial independence.Footnote 10 For independence to exist in practice, however, judges must in fact exercise this independence without repercussions from the other branches or other political forces (Hayo and Voigt Reference Hayo and Stefan2007; Ríos-Figueroa and Staton Reference Ríos-Figueroa and Staton2014). Because it focuses on behavior, this understanding of judicial independence requires taking a more holistic view, one that considers informal practices to enhance or undermine independence, such as pressure on justices from covert police activity, bribery, or threats as well as the court rulings themselves (especially in cases that deal with central political actors like the executive). As Zhenis Kembayev (Reference Kembayev2017, 314–15) describes, Nazarbayev had the ability to “significantly influence the work of the Constitutional Council” through his political control over members of the legislature, which is dominated by the Nur Otan party he heads. “In Kazakhstan’s political realities,” this means that appeals to the CCRK require Nazarbayev’s “explicit or implicit consent”—a reality reflected in the assessments of weak judicial independence from the executive cited in the previous paragraph (Kembayev Reference Kembayev2017, 314–15). In short, the CCRK reflects the common assumption that courts in authoritarian regimes inherently lack independence and meekly comply with the dictator’s wishes.

However, just because courts like these are “captured” at one point does not mean that they continue to remain fully dependent in practice. As Daniel Brinks and Abby Blass (Reference Brinks and Blass2017) show in a comparative analysis of constitutional courts in Latin America, courts can vary over dimensions of autonomy and authority (the two components these authors use to define and measure independence), in part as a function of constitutional design. This has also been true in other regions around the world. In Pakistan, for example, Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry—a judge hand-picked by General Pervez Musharraf in the wake of his successful coup, who had consistently supported him in subsequent rulings—went on to expand judicial power and, ultimately, threaten Musharraf’s political control (Ghias Reference Ghias2010). In addition, some scholars suggest that, during periods of uncertainty or perceived regime weakness, even courts that consistently acquiesced to mandates from the executive may seize the opportunity to issue “activist” rulings that challenge the status quo (Helmke Reference Helmke2002, Reference Helmke2006). Regime change—particularly when it occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, as with the collapse of the Soviet Union—is likely to feature substantial uncertainty regarding the long-term trajectory of political power. For example, although the newly independent former Soviet republics (including Kazakhstan) inherited structures of government and officials who led them, it was far from clear which officials and institutions would reign supreme in the years to come; in some countries, like Tajikistan, tensions between regional political actors led to civil war, while, in Kazakhstan and other countries, there was intense conflict between Parliament and the presidency. Such conditions heighten the likelihood that the constitutional court will flex its muscles and demonstrate a higher degree of independence than an aspiring (or current) dictator would wish.

Furthermore, extant literature tends to sidestep how courts become captured in the first place. How do executives achieve and, later, maintain their control over the constitutional court? This gap in understanding stems from a divide between studies of courts—especially those focused on judicial independence and constitutional review—under authoritarianism and under democracy. Some scholars focus specifically on democracies, including those democracies that are termed “new” or “nascent” (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003; Chavez Reference Chavez2004). Others examine judiciaries under authoritarianism (Moustafa Reference Moustafa2003, Reference Moustafa2014; Ginsburg and Moustafa Reference Ginsburg and Tamir2008; Crouch Reference Crouch2020). Both sides of the split are interested in similar questions, such as the presence or absence of judicial independence, but they look at only one type of regime. Some have argued that democracy is a necessary condition for judicial independence of the type described above (Olson Reference Olson1993; Helmke and Rosenbluth Reference Helmke and Frances2009), while, elsewhere, scholars have suggested that some judicial independence can occur even under an autocracy (Helmke Reference Helmke2002, Reference Helmke2006; Moustafa Reference Moustafa2003; Mazmanyan Reference Mazmanyan2010). This pronounced split between those who study authoritarian courts and those who study democratic courts leads to the truncating of data, which we argue contributes to post hoc selection bias and, with it, the under-examination of how courts are captured in the first place (or, conversely, gain independence where it has been absent).

More specifically, the theoretical emphasis on a binary of democracy or autocracy misses the messy reality of cases in the grey area between the two extremes. For example, when the Soviet Union collapsed, it was not immediately evident whether or which of its successor states would become democratic or authoritarian; instead, regime outcomes remained in flux, and many states saw intense contestation over the form that their political institutions would take. Yet many studies attribute post hoc inevitability to these transition periods. In a survey of judicial design across post-Soviet states, for example, Shannon Ishiyama Smithley and John Ishimaya (2000, 164–65n1) exclude the Central Asian republics from their sample as these states have not had at least “some experience with democracy.” Why should the experiences that countries have had after the design of their constitution limit which cases we use to evaluate constitutional design? Tamir Moustafa (Reference Moustafa2014) echoes this concern, noting that the “authoritarianism versus democracy” framing limits theory building. Our stance is that this framing also obscures theorizing when it comes to understanding why and how executive capture of courts occurs during transitions between regimes, including those that follow independence or violent conflict. When these states developed their constitutions and judicial institutions, it was unclear whether they were or would become democracies or autocracies; this should be clear from the erroneous conclusions early on that the Kyrgyz Republic, for example—which has undergone long periods of authoritarian rule and instability—would be a stable “island of democracy” (International Crisis Group 2001).

Similarly, one should not assume that, since Kazakhstan looks thoroughly authoritarian now, we can apply theories of authoritarian court design to the period in Kazakhstan’s history (specifically, the early 1990s) when it was unclear what shape the regime would take. As we discuss in greater detail below, Kazakhstan experienced a brief interlude in the critical juncture after the Soviet collapse—from independence in 1991 until the late 1990s—when the country’s political trajectory remained murky. At the same time, that period was crucial for Nazarbayev’s consolidation of power. We argue that, rather than taking executive capture under authoritarian rule as our default expectation, we need to look more closely at courts’ development during these periods of regime change and consolidation. In short, our discussion of the transformation of the CCRK into a reliable agent of Nazarbayev does not concern a court under authoritarianism so much as it does a court mutually constitutive with a burgeoning authoritarian system.

Scholars have shown that aspiring autocrats use various other globally accepted institutions as tools to gain and stay in power, such as elections (for a review, see Gandhi and Lust-Oskar Reference Gandhi and Ellen2009), political parties (Magaloni Reference Magaloni2006), and bureaucracies (Dixit Reference Dixit2010). Constitutional courts are a natural addition to the list of institutions that can be manipulated to facilitate authoritarian transition and consolidation, yet one that has received scant attention.Footnote 11 Moreover, they are a crucial one. As discussed above, not only do constitutional courts play an important strategic role in setting the ever-changing “rules of the game” that characterize authoritarian politics; they also represent a means to establish and maintain rational-bureaucratic legitimacy in the eyes of both domestic and international constituencies.

UNDERSTANDING COURT CAPTURE

Based on prior literature and the theories explored above, we should expect to see executives highly motivated to design constitutional courts that can be captured when their continued tenure is uncertain. They are motivated to do so as a means to control contestation over the “rules of the game” as well as the legitimate construction of their continued term in office, which is often in conflict with the original constitutions that emerge after a regime transition. In addition to this interest in controlling courts, we argue that court capture is shaped by the opportunities and constraints that the aspiring autocrat faces in this crucial period. This focus on interests, constraints, and opportunities provides a framework for our subsequent analysis and organizes the many details of the Kazakhstan case into a cohesive narrative. We define and provide examples of each factor below and then describe in detail how they interact to influence the capture of constitutional courts in regime-transition environments. Of course, opportunities, constraints, and interests, strictly speaking, do not create a generalizable theory of why or how capture occurs. They instead highlight crucial factors and turning points in the Kazakhstani case and provide a broadly applicable framework for definitively answering questions of “how” or “how not” in other cases.

Interests are the goals that executives pursue. The foremost goal of an aspiring autocratic leader is to stay in power and to be insulated from the repercussions that might arise from using that power; because constitutional courts rule on the overarching legal structure of the state, they are a linchpin in that process. This is especially true when a ruler’s hold on power is not yet consolidated. Without executive capture, the dictator cannot be confident that the court will issue rulings that facilitate, rather than undermine, his or her personal consolidation of political power at the expense of his or her opponents. This suggests that when a dictator faces a legislature or organized opposition that challenges him for political control, he will have an interest in capturing the court. While it is possible that, alternatively, a ruler could simply ignore an unfavorable court ruling that supported his political opponents, doing so could have the negative consequence of creating an opportunity for that opposition by creating a focal point for mobilizing resistance. Most dictators prefer to avoid this situation, and, thus, we expect them to try to capture the court instead.

Given this interest in controlling the court, executives then balance the potential benefits of pursuing court capture against the costs—a calculation that depends on both constraints and opportunity. Constraints refer to factors that impose costs on the executive should they attempt to remove judicial independence and could be international or domestic. For example, the international norms of juristocracy described in the previous section should be considered as a constraint to court design, as should domestic political coalitions and conditions. A well-organized bar that supports judges’ independence would be an instance of the latter.

Two types of constraints are likely to be present in the wake of regime change: the potential for elite collective action against the ruler as he or she attempts to consolidate power in their own hands and the threat of international sanctions or condemnation. Aspiring personalist rulers like Nazarbayev initially rely on the support of other elites to rule; upon assuming the presidency or executive role, they try to undermine that dependence, which in turn requires elites to coordinate against the ruler to check the attempt. This iterated game continues until elites can no longer credibly threaten the dictator’s removal or a stalemate (and continued power-sharing) ensues (Svolik Reference Svolik2012). Like disregarding court decisions, blatant attempts to hamstring the independence of important institutional actors that constrain the executive’s freedom to maneuver, such as the constitutional court or the parliament, can create a shared grievance that facilitates elite coordination against the ruler, perhaps even resulting in his removal. This threat can overshadow the benefits to be had by controlling the legal institution that certifies the formal “rules of the game.” In other words, we should expect that, where elites continue to contest the ruler’s expansion of power, any attempt to undermine judicial independence in his favor has the potential to bear a high cost.

The second type of constraint impacts aspiring autocrats primarily through its effect on the economy. Rejecting international norms regarding the creation of a constitution and juristocracy signals to the international community that the country is unwilling to “play ball” with widely accepted standards.Footnote 12 Economic growth and development play a role in maintaining regimes of all types, but legitimacy derived from government performance tends to be particularly critical for autocrats, who lack the procedural legitimacy that stems from selection in competitive popular elections (Nathan Reference Nathan2020). In addition, economic resources are critical for supporting the extensive patronage networks that underpin elite control in many countries, including Kazakhstan (McGlinchey Reference McGlinchey2011). Not unusually for newly independent countries, attracting foreign aid and investment offered the most obvious means for post-Soviet leaders to boost their collapsed economies, and, initially, most of that investment came from foreign governments: in the immediate post-collapse period, over two-thirds of capital flows in Central Asia consisted of grants and low-interest loans from bilateral and multilateral donors (Bayulgen Reference Bayulgen2005, 55). Donor governments embraced a “transitology” approach that emphasized democracy promotion and the rule of law, which in turn incentivized leaders like Nazarbayev to comply with prevailing international norms when designing their constitutions and courts (Newton Reference Newton2017). International norms thus functioned as a soft constraint by narrowing the range of options that aspiring autocrats had for designing constitutional courts; eschewing Western expectations of institutional design, including judicial independence, risked a reduction in economic support or investment exactly when countries could least afford to alienate investors or aid agencies.Footnote 13

In Kazakhstan, pressure to align with international practices in the design of constitutions and courts, coupled with contestation from domestic elites, made eliminating formal judicial independence—or the Constitutional Court itself—potentially costly. Instead, Nazarbayev waited for an opportunity that temporarily reduced those costs, making it easier to impose formal institutional changes that facilitated capture of the Constitutional Court, while, throughout, the court’s independence remained certified in the constitution. Opportunity here refers to a window of time in which the executive can temporarily influence court design at a lower cost because there has been a temporary shift, or opening, that weakens the constraints outlined above. This window represents a critical juncture or “situations of uncertainty in which decisions of important actors are causally decisive for the selection of one path of institutional development over other possible paths” and may be exogenous or endogenous to the system (Capoccia Reference Capoccia, Fioretos, Falleti and Adam2016).

A natural disaster that weakens the economic standing of internal elite rivals would be an obvious candidate for the former exogenous shock, while the latter may entail, for example, a space for constitutional reform created by an engineered political crisis (for example, a targeted assassination), a particular court ruling, or other factor that shifts the context (and, thus, the arguments) for introducing institutional reform. Aspiring autocrats can then seize on this opening to enact changes that facilitate executive capture of the court at a lower cost than they would otherwise normally face. In the case of Kazakhstan, a key Constitutional Court case provided just such an opportunity; we discuss it in further detail in the analysis that follows. Crucially, however, such opportunities are not always converted into successes. Working to take advantage of an opportunity still comes with costs, and there is always a risk that the executive will miscalculate what those costs entail. Had there been more or better-organized popular resistance to a series of moves that preceded the Constitutional Court’s reform into a council, for example, Nazarbayev might have found the route to capturing the court blocked.

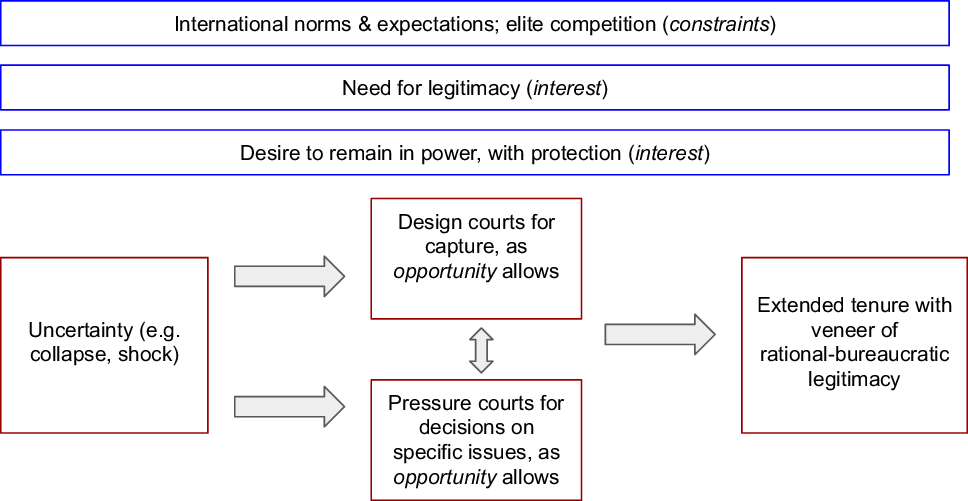

Figure 1 presents the general framework graphically. An interest in continued tenure and the consolidation of political power in the ruler’s own hands is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for court capture; constraints and opportunity must also align. While we cannot know a priori which leaders possess this interest, it generally becomes clear over time, as we see iterated attempts to limit opposition and remove obstacles—both formal and informal—to his or her continuation as president (or other formal title). In the case of Kazakhstan, Nazarbayev’s actions made his interests clear. He repeatedly took steps to reduce opposition representation in the government, for example, by making it more difficult for opposition parties to register or gain seats in the Parliament. At the same time, he removed term limits on the presidency, sought special, protected legal status for himself and his family, and, most tellingly, declared his intention to run for president for an indefinite number of terms. Through these actions, this goal of consolidating and staying in power was repeatedly and clearly demonstrated.

FIGURE 1. General framework of factors influencing capture in Kazakhstan. Credit: courtesy of the author.

Existing constraints then determine the baseline cost-benefit calculations aspiring autocrats make when deciding whether to act on their interest in capturing constitutional courts. Though they can change, these constraints tend not to shift dramatically over the short term, barring a critical juncture that creates an opportunity to instigate major changes in constitutional and court design. Times of uncertainty present both an opportunity and a challenge to leaders with the aforementioned interests and constraints. After the Soviet collapse, Kazakhstan could have gone one of many ways. Nazarbayev successfully leveraged a key opportunity to temporarily expand his power vis-à-vis a parliament that posed a significant challenge to his political control and, having done so, took advantage of that momentary opening to redesign the Constitutional Court to facilitate its capture, free of resistance from elites in the legislature. He then continued to use those formal and informal levers to ensure favorable decisions on the constitutionality of reforms down the line, thus facilitating his further consolidation of political power.

We argue that this investment in the Constitutional Court was net beneficial because it allowed Nazarbayev to claim, at least rhetorically, that his moves to extend his tenure were backed up by constitutional interpretation. In other words, engineering the constitutionality of his actions gave him cover to claim rational-bureaucratic-legal legitimacy. As our analysis shows, even after his tenure in office appeared to be secure (for example, after the upheaval of the 1990s), he continued to use the CCRK to legitimize his extended presidency. This suggests that not only do constitutional courts play an important role in authoritarian consolidation, but they also are crucial to regime maintenance.Footnote 14

THEORY IN PRACTICE: THE CCRK

In this section, we trace the process by which the original Constitutional Court in Kazakhstan was transformed into the current CCRK via a new constitution (in 1995) and a series of constitutional laws.Footnote 15 How did interests, opportunities, and constraints combine to allow Nazarbayev to design a court ready for executive capture? Our sources here are the primary documents surrounding this process, including the original laws on the Constitutional Court and the new laws on the CCRK as well as secondary sources, including an interview with one of the former Constitutional Court justices who then sat on the CCRK (Carroll and Malinovsky Reference Carroll and Malinovsky1996). To make our case, we first establish uncertainty over the rules of the game and the distribution of political power in Kazakhstan in the early 1990s. We then describe the opportunity that Nazarbayev used to reshape the court to better suit his interests while still aligning with international norms.

Uncertainty in the 1990s

Relative to the other former Soviet states in Central Asia, Kazakhstan in the 1990s at first glance appears to have been fairly stable. There was no civil war, for example, as in Tajikistan, or marked ethnic conflict, as in Kyrgyzstan. Yet scholars have consistently noted that this apparent calm concealed substantial uncertainty and political conflict, especially in the early 1900s. Any regime transition is likely to foster “a great deal of uncertainty and contingency” (Jones Luong Reference Jones2002, 104), and, in Kazakhstan, the main sources of uncertainty following the Soviet collapse derived from “heightened institutional conflict, emerging pluralism, and electoral competition” (Isaacs Reference Isaacs2010, 8). Kazakhstan in the early 1990s saw the creation of opposition parties, outspoken government critics (often driven by elite splits), and, most importantly, a feisty legislature that challenged Nazarbayev for political control.

This contention between the executive and the legislature stemmed directly from the Soviet collapse. Nazarbayev had come to the position of first party secretary of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic as a consensus candidate among Kazakh elites after Mikhail Gorbachev’s failed attempt to impose an ethnic Russian, Gennady Kolbin. That consensus reflected expectations that Nazarbayev, the protege of the previous, long-serving secretary, Dinmukhamed Kunaev, would be best able to ensure balance among the powerful, regionally based clan groups competing for power and resources (Collins Reference Collins2004, 242). As a result, Nazarbayev initially enjoyed a strong mandate to rule, and this unified support eased his transition from party secretary to president. Nonetheless, the Supreme Soviet quickly emerged as a major center of opposition to his attempted reforms and, thus, a challenge to his consolidation of political power. For while Kazakhstan’s 1993 Constitution established a strong presidency, it had also given broad powers of legislation to the Supreme Soviet. Deputies seized on that formal authority to take an active role in policy making; they came into conflict with Nazarbayev when he attempted to liberalize economic reforms that threatened the interests of many of the powerful regional elites represented in the Supreme Soviet (Isaacs Reference Isaacs2010, 11–12). The previously quiescent body was thus rapidly transformed into a center for opposition to Nazarbayev’s economic policies.

Conflict over economic reform left Nazarbayev and the legislature at an impasse. Soon afterward, it self-dissolved. Commentators at the time suspected that Nazarbayev struck informal deals with its speaker and enough other legislators to dissolve Parliament and hold new elections (Cummings Reference Cummings2005, 25; Isaacs Reference Isaacs2010, 12). Those elections subsequently returned what should have been a more pliable group of members of parliament (MPs) to the legislature; many of the candidates were picked from a “state list” by Nazarbayev himself, and a new pro-presidential party created by Nazarbayev won the largest number of seats in the assembly (Cummings Reference Cummings2005, 25). However, even that careful maneuvering and co-optation proved insufficient. Nazarbayev again found himself locking horns with MPs over economic reform, and the pro-presidential block did not prove to be the reliable partner for which the president had hoped. That conflict between the executive and the legislature came to a boiling point in May 1994 when Parliament passed a vote of no confidence in Prime Minister Sergei Tereschenko over the proposed privatization program, forcing Nazarbayev’s point man in the assembly to step down (Olcott Reference Olcott2010, 10). This presented a critical moment for Nazarbayev and one where the actions of the constitutional court could prove decisive: with the future balance of power between the executive and legislature so hotly contested, the court’s power of constitutional review represented a potent potential weapon for either side.

Then, in March 1995, came a critical opportunity for Nazarbayev: Tatyana Kvyatkovskaya, a candidate in the race for Parliament from Almaty, petitioned the Constitutional Court, claiming that the elections had been unconstitutional because the much larger number of voters in her district compared to much smaller districts in Almaty violated her right to equal representation (Cummings Reference Cummings2005, 26; McGlinchey Reference McGlinchey2011). The court upheld her claim in a ruling on March 6, 1995, that annulled not just Kvyatkovskaya’s race but also the entire election. Some commentators interpret this as the court taking an activist position (ZONAKZ 2004), while others interpret it as the court following the president’s prompting (Cummings Reference Cummings2005, 26). Regardless, the decision marked a pivotal moment in post-independence politics and one that Nazarbayev seized on in his iterated conflict with the legislature. He contested the Constitutional Court’s decision, in what Rico Isaacs (Reference Isaacs2010, 17) refers to as “clever political protests,” but was promptly overruled by the court. Nazarbayev then used the court’s decision as a justification to dissolve Parliament and call for entirely new legislative elections in December 1995. MPs reacted with dismay, with over seventy individuals reportedly taking part in a hunger strike in protest (Kagarlitsky Reference Kagarlitsky1995, cited in Isaacs Reference Isaacs2010, 17). Until the new elections were held—a nine-month period—Nazarbayev ruled without any legislature.

In that critical interregnum, when MPs could not mount legislative resistance, he held a national referendum that capitalized on his high level of personal national recognition and popularity to introduce a new Constitution with significant changes: it substantially increased his powers at the expense of the legislature (Cummings Reference Cummings2005, 26–28; Isaacs Reference Isaacs2010, 17), extended his presidential term until 2000, and introduced a bicameral legislature, with the lower chamber elected through direct popular vote and the upper chamber selected through a combination of indirect election by regional and city legislatures (forty seats seats) and appointment by the president (seven seats) (Bowyer Reference Bowyer2008, 44). These maneuvers complicated MPs’ ability to coordinate against the president and effectively shut out opposition-minded deputies. Though some continued to try to mount challenges from outside Parliament through the early 2000s, 1995 proved to be a turning point in Nazarbayev’s consolidation of power and in Kazakhstan’s path to personal authoritarian rule (Isaacs Reference Isaacs2010, 1).

The same 1995 Constitution that hobbled Parliament as an institutional actor also transformed the Constitutional Court into the Constitutional Council—a body redesigned in ways that made it far more susceptible to executive capture (formal and informal), while remaining formally independent. Members of the former court protested the transformation in a 1995 letter and raised concerns about the constitutional reforms more broadly (Baimakanov et al. Reference Baimakanov, Rogov, Nurmagambetov, Basharimova, Malinovskiy and Udartsev1995). This is evidence that creating the new Constitution was not costless and that key elite actors at the time recognized the dangers of the new institutions. Yet, in this case, the risks paid off for Nazarbayev. Before turning to how these reforms facilitated executive control over the constitutional review process, we examine in the next section the crucial court ruling that provided Nazarbayev with an opportunity to simultaneously tame not only the legislature but also, ironically, the very Constitutional Court that issued that decision.

Redesigning for Capture

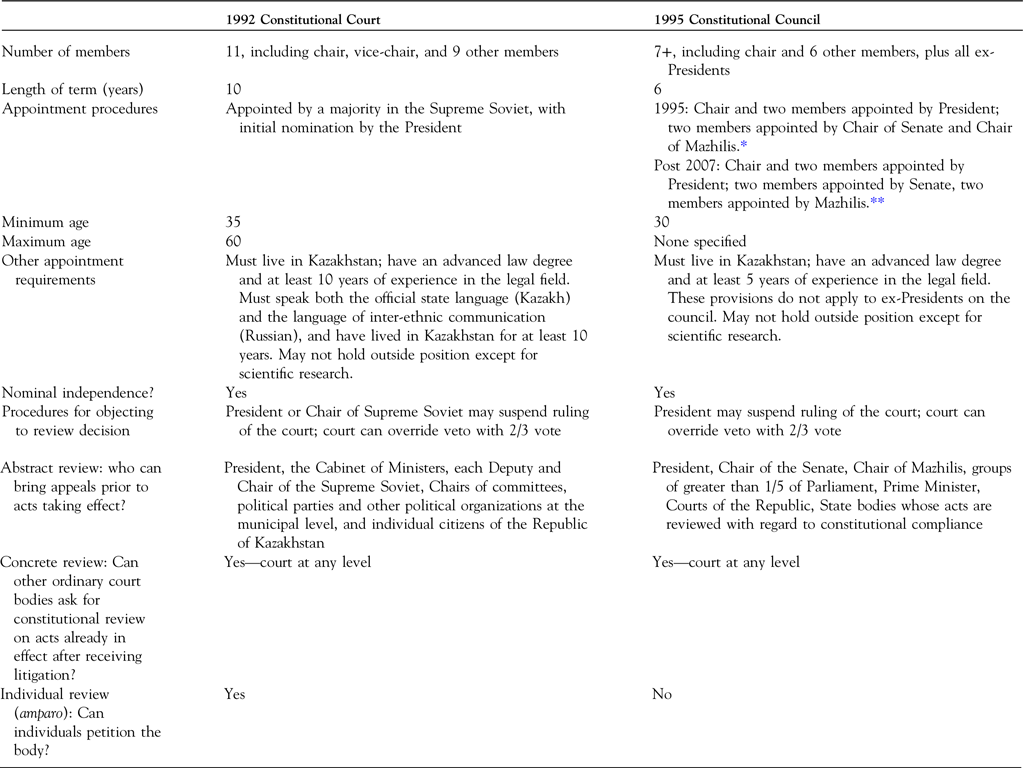

Kazakhstan officially declared its independence from the Soviet Union with the Constitutional Law on State Independence, adopted on December 16, 1991.Footnote 16 The Constitutional Court was created as a part of this law, and it continued its existence in much the same form through the creation of a new Constitution in 1993. As the previous section describes, the scuffle over constitutional law that ended in the creation of the CCRK began in 1994, with the parliamentary elections on March 7. As detailed above, the “Kvyatkovskaya affair” gave Nazarbayev a window of opportunity to change the rules for Parliament, but he also took that opportunity to attempt to extend his own legitimate tenure in office and to capture the Constitutional Court. First, a referendum was initiated through the newly created Assembly of People of Kazakhstan (APK), an unelected body established by Nazarbayev to represent the interests of the various ethnicities present in Kazakhstan, to extend the president’s term in office until 2000.Footnote 17 This answered the question, at least temporarily, of the president’s continued tenure in power. Second, in the new Constitution, the Constitutional Court was reformed as a council, with the features described in Table 1.Footnote 18 This version of the Constitution went into force on August 30, 1995, after it received over 95 percent approval from Kazakhstani voters in a referendum on August 29.

Table 1. Features of the 1992 and 1995 Constitutional Review Bodies in Kazakhstan

Sources:

Constructed based on five main documents: (1) the 1993 Constitution (available in Russian here: http://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K930001000_); (2) the 1992 Law on the Constitutional Court (available in Russian at http://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=1001172) [Zakon Respubliki Kazakhstan ot 5 iiunia 1992 goda No. 1378XII O Konstitutsionnom Sude Respubliki Kazakhstan]); (3) the original 1995 Constitution, prior to amendments, in Russian (Zimanov Reference Zimanov1996, 331–33). We thank Krisoffer Rees for pointing us to this source; (4) the 1995 Constitution, including all amendments made up to 2011 (available in Russian at http://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/K950001000_); (5) the 1995 Law on the Constitutional Council (available in Russian at http://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/U950002737_) [O Konstitutsionnom Sovete Respubliki Kazakhstan Konstituttsionnyi zakon Respubliki Kazakhstan ot 29 dekabria 1995 g. N 2737].

Notes:

* The Senate is the upper house of the two-chamber Kazakhstani Parliament. The lower house is called the Mazhilis.

** This change was made in a 2007 law. The change grants slightly more power to the two legislative bodies, which are now tasked as a group to select members of the council, instead of the chairs of each body selecting members as individuals. However, the effect of this change on the degree of executive capture is minimal, if it exists at all: the president still appoints the council chair and two members.

In other words, the process by which the court was transformed into the council reflected a confluence of opportunity, constraints, and interests. There was opportunity: the dissolution of Parliament put their powers into the hands of the president. He did not, however, dissolve the review body entirely. The president instead seized the opportunity to change its structure to facilitate formal executive control over the council to ensure his influence on future decisions regarding the rules of the executive-tenure game. Table 1 compares the 1993 Constitutional Court to the 1995 Constitutional Council. There are a number of institutional changes suggesting that the CCRK was more susceptible to executive capture than the court. The members of the council have shorter term limits, which allows the president to more rapidly dismiss misbehaving members or to threaten to do so to ensure a favorable outcome. Three out of the seven council members are directly appointed by the president, which is a major change from the court appointment procedures, which went through the Supreme Soviet. Thus, a significant contingent of the judges are beholden to the president rather than the legislature. Moreover, after 1995, only the president—rather than the legislature—could overrule council decisions, and forming the two-thirds majority to override him would require at least one judge who he appointed to vote against his action. In addition, ex-presidents are given a seat on the council—a provision that has added weight given Nazarbayev’s recent decision to step down from the post of president. Both documents note that the judicial body should be independent from outside influence, but if a member of the council knows that they will have to engage with the president indefinitely after he or she leaves office, they may be less likely to rule against the executive-backed laws and acts.

Access to the CCRK—an issue separate from executive capture but related to the ability of the council to meaningfully address issues—is also far more restricted than access to the Constitutional Court. While this may allow the court to be more efficient, in that it has had fewer cases to deal with, it is also arguably less democratic. After 1995, citizens could no longer bring petitions, except through the mechanism of lower courts (Carroll and Malinovsky Reference Carroll and Malinovsky1996). These changes limit the independence of the council and its responsiveness to citizens’ complaints. Effectively, they also close off the avenue by which Kvyatkovskaya was able to petition the court in 1995, thus narrowing the council’s ability to consider cases that could have a marked impact on the overall landscape of Kazakhstan politics; this in turn reduced the council’s own opportunity to potentially serve an activist role by ensuring that access was largely confined to other government institutions (whose leadership are predominantly appointed by the president). In essence, formal shifts in who could activate the process of constitutional review reduced the likelihood of “surprise” rulings.

Prior to its transformation into a council, the Constitutional Court had ruled on about fifteen matters, including questions about property rights, the budget, and elections (Carroll and Malinovsky Reference Carroll and Malinovsky1996; Amandykova and Malinovskyi Reference Amandykova and Viktor2012). The texts of these decisions are difficult to come by, and it is similarly difficult to assess the independence of the court in making these decisions, but the court does not appear to have been particularly adversarial against the president. The same cannot be said of its relationship to Parliament. For example, the court ruled that Parliament violated the president’s veto powers when it made changes to an international treaty before sending it to the president for final approval (Carroll and Malinovsky Reference Carroll and Malinovsky1996). Isaacs (Reference Isaacs2010, 28) suggests that the court was influenced in the 1995 decision by informal connections to Kairbek Suleimenov, a deputy minister of internal affairs who was then rapidly promoted to minister of the interior.

Yet, despite the generally friendly rulings of the court, Nazarbayev surprised at least one member of the court by investing in capture: when asked about the changes to the court in 1995, former justice Victor Malinovsky was quoted as saying: “The ‘birth’ of the Constitutional Council came down like lightning from the sky without disclosure to the political movements involved or formal legislative approval of the President’s decision. Overall, the competence of the CCRK is limited in all respects” (Carroll and Malinovsky Reference Carroll and Malinovsky1996, 110). Malinovsky also noted that the time frame in which the court may produce decisions over new laws was shortened under the new provisions (110). Footnote 19 In short, circumscribing the court’s authority by transforming it into a council in this manner—and without apparent input or approval by sitting justices—suggests that Nazarbayev viewed the independence of the court as being too risky to let stand and prioritized extending his control over the institution with the formal authority to adjudicate the rules of “legitimate” tenure in office.

LEVERAGING THE CCRK: FOUR CASES OF INTEREST

It is clear from the design of the CCRK that Nazarbayev has many potential sources of leverage in order to influence decisions. What does it look like when that influence is exerted? To answer this question, we examine four periods where Nazarbayev “won” in a CCRK decision or a series of linked decisions. All four (in 1998–2000, 2005, 2011, and 2015) were favorable toward Nazarbayev’s extended tenure in office.Footnote 20 In 1998, constitutional amendments allowing Nazarbayev to run and scheduling snap elections were passed. The CCRK approved those changes. In July 2000, the CCRK approved as constitutional the new Law on the First President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, which provided him powers ex officio and laid the groundwork for future laws that removed term limits for Nazarbayev and granted him protection from any future prosecution.Footnote 21 In 2005, a CCRK ruling moved up the presidential elections. In 2011, the CCRK ruled that a law proposing to extend the president’s tenure by a referendum (to be held ahead of the scheduled elections) was unconstitutional: the law had been passed by the Parliament, but the president asked for a ruling by the CCRK (despite the fact that the original referendum proposal likely originated with the executive). In 2015, the CCRK ruled that only the president could call for presidential elections. The day after the decision, Nazarbayev scheduled early elections.

For each case, we briefly discuss what led up to the CCRK case, the decision(s), and the impact (practical and rhetorical) of the ruling. We then compare the decision(s) in each case to the average CCRK ruling, utilizing a newly compiled database, which is described below. The aim in doing so is twofold: first, we demonstrate that each decision comports to theoretical expectations. In each instance, Nazarbayev was able to extract a favorable outcome and used that outcome to claim that his continued tenure in office was legitimate on constitutional, popular, and/or democratic grounds. Second, we delve into the details of the decisions themselves to see if we can find traces of executive influence in the formal CCRK documentation.

1998–2000; Groundwork for 2007 and 2010

The period of 1998–2000 continued to be tumultuous in terms of consolidating Kazakhstani autocracy. Elections were originally supposed to be held in 2000, according to the 1995 referendum that extended Nazarbayev’s term (for more on the constitutional crisis of 1995–96, see the description above). However, in September 1998, parliamentarians suggested moving the election to 1999. Bruce Pannier (Reference Pannier2015) writes that “in a good example of the theatre of Kazakh politics, Nazarbayev rejected the proposal. Sensitive to claims of authoritarianism he ensured the appearance of a political process.” On September 30, 1998, amidst the constitutional and electoral wrangling, Nazarbayev gave a speech reiterating the nation’s commitment to free and fair elections, an independent judiciary, and human rights. This suggests a desire to maintain a rhetorical high ground to satisfy international and domestic audiences while simultaneously working behind the scenes to ensure continued tenure in power; in short, it speaks again to the pressures to outwardly align with international norms that stressed democracy and rule of law. Nazarbayev was signaling a willingness to rely on constitutionalism and rational-legal forms of legitimacy.

Yet the rhetorical commitment was betrayed by the full course of events. Despite Nazarbayev’s ostentatiously public rejection of the proposal, the parliamentarians would not be deterred. They met with the president behind closed doors to “convince” him that early elections were warranted. In October 1998, constitutional amendments were passed to remove the requirement that presidents had to be younger than sixty-five years old and could not serve more than two terms. Presidential term lengths were also extended from five years to seven. The amendments were brought to the CCRK and passed in December 1998. Presidential elections were held on January 19, 2000, and Nazarbayev won with over 80 percent of the vote.Footnote 22 In a report from the election monitors for the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (1999), the moving up of elections was listed as the first area of concern regarding the election. Potential opposition candidates were unable to participate fully due to the scheduling.

Activity in the CCRK in 2000 further clarified the constitutional legitimacy of Nazarbayev’s continued term in office based on the 1999 election and the 2000 Law on the First President of Kazakhstan.Footnote 23 The first 2000 ruling of interest upheld the notion that Nazarbayev was justified in running in the 1999 election. The CCRK found that the two-term-limit provision would not have applied to Nazarbayev even if the provision were still in effect. They decided that his earlier term based on the referendum of 1995 should not be counted in the tally of his terms. Why a referendum election-based term should be different from a general election-based term is not fully explained in the published decision. The second 2000 ruling found that the First President of Kazakhstan Law, which granted Nazarbayev new powers, was constitutional. Interestingly, although the law was extremely favorable to Nazarbayev, the president himself asked for the CCRK’s ruling on the law. Challenging the extension of his own powers allowed him plausible deniability of authoritarian tendencies: by appealing to the CCRK for constitutional review, he was able to claim that his extended rule was simply the will of the people, as expressed by the Constitution and upheld by the court. In other words, he could claim legitimacy of continued rule on legal-rational, constitutional grounds.

The First President of Kazakhstan Law and the constitutional provisions it altered were then further amended in 2007 and 2010. The 2007 law, which was reviewed by the CCRK on June 18 at the request of the Mazhilis (the lower house of the legislature), was found to be constitutional—though, when examining the decision itself, one finds that the questions put to the council were more concerned with the powers of the Mazhilis than with the powers of the president. The points raised by the Mazhilis and reviewed in the June 18, 2007, ruling clarify the powers of Parliament to make constitutional changes and self-dissolve, not whether the content of their changes were constitutional.Footnote 24 However, the very existence of the decision (regardless of the actual content) allows for a claim that the entire law passed constitutional review, despite the fact that the term-limit provision went unchallenged in the decision. In 2010, a new law passed that granted the president protection from prosecution after leaving office.Footnote 25 The 2010 law, while it was not brought before the CCRK, demonstrates the usefulness of a body of captured constitutional law and favorable decisions to an increasingly entrenched autocrat: by the time Nazarbayev was granted this exemption from prosecution, he had already grounded his special status in constitutional interpretation legitimated by the council.

2005

In 2005, a dance similar to the 1998–99 confusion ensured another early presidential election. Presidential elections were initially scheduled for December 2006, but, as Nazarbayev had been inaugurated in January 1999, this would leave him without an electoral mandate from January 2006 until the elections in December 2006. In June 2005, the Mazhilis appealed to the CCRK for a decision on when the next presidential election should be held. On July 3, the court ruled that the election should be held on the first Sunday in December 2005, a year early. Opposition candidates were not surprised by the ruling (consider, for example, that representatives of Nazarbayev’s party gave statements in favor of the 2005 date), but, again, they were caught with a shorter time period to prepare for the election (Pannier Reference Pannier2005). Nazarbayev won the election with 91 percent of the vote. Significant shortcomings in the conduct of the election were again noted by the OSCE (2005). Since the decision for an early election came not from the president, but, instead, from a constitutional review process, Nazarbayev could once again claim that his victory was rooted in rational-bureaucratic authority.

2011

The 2011 election introduced a new wrinkle: a popular petition for extending Nazarbayev’s tenure. The OSCE’s election report provides a concise summary of the events:

The 3 April early presidential election came in the aftermath of a citizens’ initiative to hold a referendum which would have extended the term of incumbent President Nursultan Nazarbayev until 2020. Between 26 December 2010 and 14 January 2011, over 5,200,000 signatures were reportedly collected in favor of the referendum.Footnote 26 On 7 January, the president refused parliament’s proposal to hold the referendum, but on 14 January both chambers of parliament adopted a law on changes to the Constitution, providing the legal basis for holding a referendum to extend the first president’s term of office. The president expressed concern over the constitutionality of these amendments and referred them to the Constitutional Council which ruled on 31 January that the law was unconstitutional as it was too vague on the terms of extension. Following this ruling, the president proposed that an early presidential election be held. On 3 February, parliament adopted the constitutional amendments to allow the president to call an early presidential election, and the next day, the president set the election date for 3 April. (OSCE 2011, 4)

The events allowed Nazarbayev to claim that the extension of his tenure was legitimate on a legal-rational basis. By rejecting the referendum idea and instead going through the CCRK, he could claim constitutional legitimacy in holding early elections. Killing two birds with one stone, it was also an opportunity to censure the Parliament—the CCRK found that their law was unconstitutional while simultaneously giving Nazarbayev an opening to shape constitutional amendments to his liking. Nazarbayev ultimately won the early election with about 95 percent of the votes.

2015

On April 26, 2015, Nazarbayev was reelected for another term in office with a reported 97.5 percent of the vote and 95 percent voter turnout. As usual, both the results and the conduct of the elections were subject to critique from both home and abroad.Footnote 27 Nazarbayev’s response, in a post-election press conference, was the following: “I am sorry that for the ‘super-democratic’ states these figures are unacceptable—95 percent turnout, 97.5 percent for me. But I could not do anything about it.Footnote 28 If I had interfered, I would have been undemocratic, correct?”Footnote 29

Nazarbayev was last elected president in 2011 (see the discussion of this case above). According to the regular constitutional schedule, the next election should have been held in 2016. However, on February 14, 2015, the APK proposed that early presidential elections should be held. The APK’s rationale was twofold: first, the president’s term needed to be extended past 2016 in the interest of economic stability, and, second, if elections were held in 2016, they would coincide with parliamentary elections, which is not allowed under the Constitution.Footnote 30 The Parliament supported the APK’s initiative and sent a petition to the president asking if he would hold snap elections. Additional organizations also supported the petition, including the Alliance of Bloggers, which went even further and called for a referendum extending the president’s term in office until 2020 instead of holding snap elections (Ageleuov Reference Ageleuov2015). The Senate also requested an official interpretation from the CCRK as to whether or not Parliament could call for the snap elections themselves.

The CCRK, in its turn, held in a decision on February 24, 2015, that only the president could call elections. Their ruling supported the rationale of the original APK proposal, noting the unconstitutionality of the looming scheduling conflict between presidential and parliamentary elections in 2016.Footnote 31 On February 25, the day after the CCRK’s decision, Nazarbayev announced on television his decision to call for early elections. In his announcement, Nazarbayev cited the unconstitutionality of holding parliamentary and presidential elections at the same time. He also noted that there were two proposals—one for early elections and one for a referendum—and stated:

Both proposals are feasible, but the more correct option, based on the requirements of the Constitution, is the holding of elections. Therefore, in the interest of the people, and considering their request to me, their general will, and to be in accordance with the Fundamental Law, I have made a decision and in accordance with Paragraph 3.1, Article 41 of the Constitution I have signed a decree setting irregular presidential elections for April 26, 2015.Footnote 32

In 2015, therefore, the series of events and rhetoric strongly suggest a behind-the-scenes power dynamic undertaken to allow Nazarbayev to stay in office while maintaining a veneer of constitutional legitimacy.

THE CCRK DATABASE AND KEY DECISIONS IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

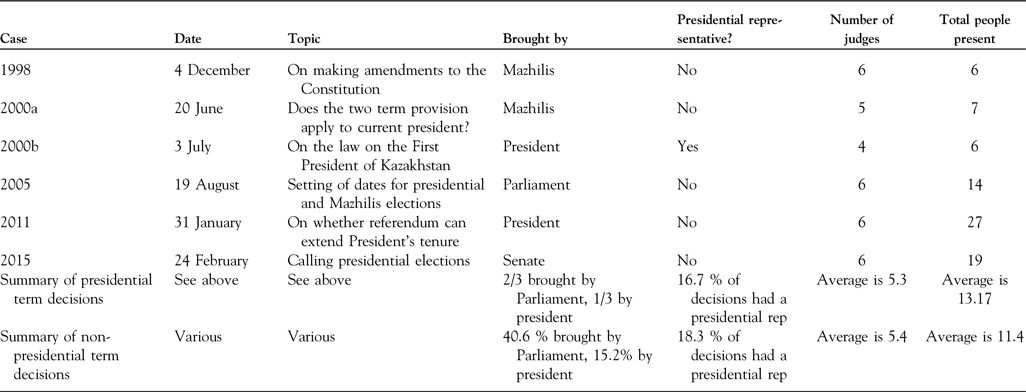

We next compare the official decisions from each case to the average CCRK decision, leveraging an author-compiled database of CCRK decisions.Footnote 33 The aim of this analysis is to examine whether or not executive pressure on the CCRK can be operationalized based on the characteristics of the formal decision documents, primarily by examining who is in the room when CCRK decisions are made. There are two main reasons to highlight who is listed as present during the discussions. First, representatives of the president might be vehicles of autocratic pressure (just as representatives from other groups serve as advocates for their group’s position). At a minimum, they are able to convey directly to the council the preferred logic of the ruler. Their presence might also serve as a subtle threat or reminder of power dynamics. Yet pressure on decisions is also quite likely to happen behind the scenes, not in the public arena. Thus, the second potential function of a representative in the room is therefore less about possible pressure and more about public signaling. Having a deputy present demonstrates the importance of the issue to the leader—the discussion is worth the time of an aide. It allows for a public narrative of respect for the constitutionality of actions, working toward the goal of rational-bureaucratic legitimacy.

We compare the decisions from the four cases of interest to the average CCRK decision to see whether these favorable decisions differed from the average decision on the measures of interest. To do so, we compiled all of the decisions made available in Russian by the CCRK on its website in 2015, for a total of 143 decisions.Footnote 34 These decisions are divided on the website into four categories (see Table A1 in the Appendix). Three additional categories are listed on the website, covering issues of treaty ratification, elections, and issues arising out of paragraphs 1 and 2 of Article 47 of the Constitution. Curiously, all three of these categories have no decisions listed, though decisions under the first four categories listed did wrestle with issues of elections and treaties. A final category—comprising annual speeches from the CCRK to Parliament—was excluded from the analysis.

The CCRK’s decisions follow a fairly set format, though it is clear from looking at the decisions over time that the format has become more standardized since the early days of the council. Each decision was manually coded according to variables of interest. Binary variables indicated whether a decision related to presidential term in office or to elections. In total, 9.1 percent of cases (thirteen in total) covered elections (at any level),Footnote 35 while 4.1 percent (six in total) related to the presidential term in office. Categorical and numeric variables include decision date, topic, and the law, previous CCRK decision, or constitutional provision being addressed. We have also noted the outcome of the decision, including whether or not a law, act, or prior resolution was declared unconstitutional.

We have noted which organizations were represented during the appeal and also the number of individuals from each organization. For example, a given decision might be coded as having the chair of the CCRK present, along with four other CCRK justices, two representatives from the Senate, one from the Financial Ministry, and three experts. After coding for the number of individuals from each organization, we then summed for a total measure of the number of individuals in the room. The total ranged from five to twenty-seven individuals. In total, 18.2 percent of decisions (twenty-six total) were made with a designated presidential representative in the room. Also coded for was whether an individual was designated as a representative of the petition and, if so, which organization that individual was from. In 3.5 percent of cases, the petition was represented directly by a presidential deputy. The decisions were further coded based on who brought the original appeal. The largest number—sixty decisions— were brought by the Parliament (either one of the bodies or both together). Presidential appeals were tied for second (at twenty-three) with those from lower courts (regional, city, or oblast) and those from the prime minister.

Table 2 shows how the decisions from the four cases of interest stack up against the remaining decisions. They appear to be close to the average number of decisions across most measures of interest. Non-tenure cases, for example, had a designated presidential representative 18.3 percent of the time, compared to 16.7 percent of the tenure-related cases. The difference here is in the opposite direction as expected. Thus, on its face, it appears that presidential representatives are not more likely to appear when there is a presidential tenure case before the court. Nor do these decisions have many more or many less individuals in attendance. This analysis illustrates the difficulty in detecting executive pressure in official CCRK documentation. As described above, the term length of CCRK justices and their appointment procedures appear to be designed for relatively easy executive capture. How the principal-agent problem inherent in this delegation of power is managed may not be revealed in the CCRK decisions. Perhaps because the desired direction of the decisions was more obvious in decisions concerning tenure, for example, presidential representatives were deemed less necessary than in cases where there was more room for subtlety in interpretation.

Table 2. CCRK decisions from four key cases compared to average decision

CONCLUSION

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Kazakhstan faced a period of political uncertainty and upheaval. The relationship between the president and Parliament, in particular, was on shaky new ground, with the formerly tame legislature repeatedly challenging President Nazarbayev for political power. This case illuminates why a constitutional court capture strategy is appealing to an aspiring autocrat in a post-regime-change environment: it provides a lever of control over the rules of the new political game as well as normative justification for those rules, which enhances their legitimacy. While international norms and domestic political resistance challenged Nazarbayev’s initial attempts to consolidate power in his own hands, seizing on the opportunity provided by a court ruling allowed him to overcome those barriers and to redesign the court to ensure that, in the future, it would not become a center of resistance like Parliament. This institutional reform complied with the international norms of formal judicial independence, while, nonetheless, making it more susceptible to executive capture, and, in so doing, transformed it into a more reliable vehicle for the president. Nazarbayev then turned to the CCRK repeatedly throughout his time in office to justify changes to the Constitution that supported his continued tenure. As our analysis of CCRK cases shows, the council has served as a means of legitimation for Nazarbayev, repeatedly finding logics (however contorted) to explain that his long tenure in office was indeed compatible with the procedures and principles detailed in a (nominally) democratic constitution.

Our analysis of Kazakhstan speaks to broader questions in the literature of captured institutions under authoritarianism. However, our work also highlights the importance of moving away from a strict division between analyses of authoritarian or democratic courts. The border between authoritarian courts and democratic courts is blurry, and scholars gain by examining cases in the uncertain ranges. We have shown that the CCRK falls under the model of “authoritarian constitutionalism” (Trochev and Solomon Reference Trochev and Solomon2018; Crouch Reference Crouch2020) or “autocratic legalism” (Scheppele Reference Scheppele2018), and we focused our attention on the process by which judicial or quasi-judicial constitutional review bodies are captured and then leveraged to maintain these regimes. In Kazakhstan, that process produced a body that, over time, leveraged its authority over law to consistently reinforce the idea that the extended tenure of the president had constitutionally based legitimacy. It is a strategy with parallels among other autocratic leaders in the post-Soviet region and beyond: Vladimir Putin, for example, stepped aside to allow Dmitri Medvedev to assume the presidency in nominal accordance with the constitutional limits then in place, before returning to power after Medvedev’s term had ended. With concern building about democratic backsliding in neighboring countries like Kyrgyzstan (Voss Reference Voss2021) and Mongolia (Croissant and Diamond Reference Croissant and Larry2020), potential autocrats there might also look to Kazakhstan to learn how to successfully capture constitutional review and legitimize their continued hold on the executive.