INTRODUCTION

Speaks in heavy Singlish and dialect. Looks worn out (clothes and energy level). Lower level of education.

(Respondent in a survey, defining low class in Singapore;

Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy 2019:14)

Standard English is vital for Singaporeans to earn a living and be understood not just by other Singaporeans but also English speakers everywhere. But English is not the mother tongue of most Singaporeans. For them, mastering the language requires extra effort. Using Singlish will make it harder for Singaporeans to learn and use Standard English. Not everyone has a Ph.D. in English Literature like Mr. Gwee, who can code-switch effortlessly between Singlish and Standard English, and extol the virtues of Singlish in an op-ed written in polished Standard English. (Chang Li-Lin, Prime Minister's Office, Reference Chang2016)

The above statements can be perceived as metapragmatic evaluations of Singlish, a colloquial form of English in Singapore. Certain social meanings are attached to the speaker of a register, drawing indexical links (cf. Silverstein Reference Silverstein2003) between a linguistic repertoire (i.e. Singlish) and ‘particular social practices and with persons who engage in such practices’ (Agha Reference Agha and Duranti2004:24; i.e. individuals with low education; confounded by acquiring Standard English). This very process—where distinct forms of speech come to be socially recognized as indexical of speakers’ attributes by a community of language users—has been conceptualized as ‘enregisterment’ (Agha Reference Agha and Duranti2004; Johnstone Reference Johnstone2016).

In this vein, Lee (Reference Lee2023) attempts to characterize the enregisterment of Singlish via a case study of a book Spiaking Singlish by Gwee Li Sui, a Singaporean poet. Lee (Reference Lee2023:244–47) begins by evaluating the language use in the book, asserting that it ‘involves resemiotizing formal features’ of Singlish ‘into textual resources for a ludic metadiscourse’, different from everyday Singlish use (Lee Reference Lee2023:246). He goes on to discuss the social meanings associated with Singlish use via enregisterment, suggesting that the third-order indexicality occurs as speakers utilize the link between Singlish and national identity (a second-order indexicality) to produce rhetorical, ludic performances of Singlish, in order to disrupt the dominant idea of Singlish being deviant (Lee Reference Lee2023:248–51). To Lee, the Singlish in Spiaking Singlish invokes this third-order meaning. Crucially, he suggests that a substantial segment of Singapore's population comprises ‘monolectal Singlish users who have little or no access to a comprehensive repertoire of Standard English due to, inter alia, relative lack of education’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:243). Consequently, the key claim by Lee is that Spiaking Singlish only ends up producing an ‘elitist language’, with its features and indexical qualities ‘inaccessible to its lay speakers’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:242).

This article serves as a rejoinder to Lee (Reference Lee2023). An academic response is required for two reasons. First, there is a need to clarify the indexical relationship between social meanings and registers as constitutive of, but not equivalent to, a subjective social reality. The stereotypical associations that people (including the state) often make regarding a register and its speakers (e.g. stereotypes to do with race) ought not be treated as objective fact. If we consider language as being deployed and used as a resource by humans in social life, then ‘there is always… an identifiable set of relations between singular acts of language, and wider patterns of resources and their functions’ (Blommaert & Dong Reference Blommaert and Dong2010:7). Thus, language has to be perceived as an integral part of social structure and relations, and can be studied as such. This means undertaking a methodological approach that accounts for ‘real historical actors, their interests, their alliances, their practices and where they come from, in relation to the discourse they produce’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert1999:7). In other words, the quotes above produced by the survey participant and the Prime Minister's Press Secretary are the very sort of discourse that require nuanced investigation, rather than reproduced uncritically.

Second, scholars and our scholarship contribute to public discourse and understandings, so that there are consequential representations of social groups and subjects. In my view, Lee's (Reference Lee2023) article presents an essentialist denotation of Singlish use and its users that I believe deserves an alternative, more complex iteration. Indeed, Lee's (Reference Lee2023) claims (much of which is aligned with state discourse), taken together with this article, form an overview of the language ideological debates (Blommaert Reference Blommaert1999) surrounding Singlish in Singapore society today. This article, like Lee's (Reference Lee2023), might therefore be taken as part of a larger ‘politics of representation’ (Mehan Reference Mehan, Wetherell, Taylor and Yates2001), where there is a ‘struggle for authoritative entextualisation… over definitions of social realities: various representations of reality which are pitted against each other—discursively—with the aim of gaining authority for one particular representation’ (Blommaert Reference Blommaert1999:9).

While this is an article that challenges Lee's arguments and key claims, it is also concerned with concomitant theoretical and empirical questions about enregisterment as a process in Singapore's context. Is enregisterment always straightforward in linking linguistic repertoires and meanings? What if some of these linkages and social meanings are contested by various groups? How should sociolinguistics represent potentially contested meanings when describing processes of enregisterment?

Accordingly, I attend to three main issues in Lee (Reference Lee2023):

(i) Metapragmatic claims about Singlish features in Spiaking Singlish

(ii) Theorisation of enregisterment as a process

(iii) Assumptions about Singlish speakers, with specific reference to the ‘monolectal Singlish user’

In what follows, I first address Lee's (Reference Lee2023) depiction of the ludic quality in Spiaking Singlish by drawing on a broader range of Gwee's literary works involving Singlish, as well as examples of Singlish use in wider society. I argue that the Singlish features deployed by Gwee in Spiaking Singlish are not novel nor innately ludic. Rather, these are banal forms of stylization prevalent in everyday discourse, and widely deployed by users before Gwee. Lee's (Reference Lee2023) portrayal of Spiaking Singlish as ludic might therefore be a narrow metapragmatic evaluation and interpretation in itself, with possible other stances and meanings that readers might potentially formulate.

In relation to Lee's (Reference Lee2023) narrow interpretation, I then address how enregisterment can be understood as a contested process, where there is ideological room for new meanings to emerge. Such a theorisation is based on Butler's (Reference Butler1990, Reference Butler and Shusterman1999:157–58) assertion about the possibility of social transformation through language use, by invoking the metaphor of sedimentation (Butler Reference Butler and Shusterman1999:120; Hopper Reference Hopper and Tomasello1998 in Pennycook Reference Pennycook2004).

Lastly, I argue that the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ is a classist and reductionist imaginary, unsupported by actual sociolinguistic data. In claiming that the form of Singlish use in Spiaking Singlish is elitist, Lee (Reference Lee2023) makes the assumption that a substantial segment of Singapore society only has access to basilectal English (i.e. Singlish), with the added implication that these individuals are lowly educated and socially immobile. I interrogate this premise by looking at recent research on Singlish use in English language classrooms, as well as the latest census data.

Taking all the above discussion as a whole, Spiaking Singlish need not be seen as appealing only to a small elite circle, but contributing to ever-changing attitudes towards Singlish in the public sphere. This article is an alternative iteration to Lee's (Reference Lee2023) that has implications for the way we understand enregisterment in Singapore and choose to represent it as a process.

THE LUDIC QUALITY OF SPIAKING SINGLISH

According to Lee (Reference Lee2023), the ludic quality of Gwee's Singlish use in the book emerges as a consequence of two factors. (a) ‘the (mis)alignment of a vernacular with sophistication points to a self-mocking, tongue-in-cheek undertone that informs the entire work’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:245); and (b) ‘the ludic quality… derives in part from the way it defamiliarises Singlish… the individual terms… are collocated with such intensity as to give rise to a hyperbolic display of street multilingualism’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:245–46).

As we consider the potential meanings evoked by Spiaking Singlish, it is first important to note that Singlish does not exist as ‘a fully extensive social language’ (Wee Reference Wee2011:78). To Wee (Reference Wee2011), Singlish, unlike Standard English, does not possess sufficient lexicogrammatical resources that allows it to be used as a medium for conducting entire exchanges. In this way, ‘most Singlish usage involves switching between Singlish and Standard English. . . Singlish is usually interspersed with other lexicogrammatical constructions that are more or less standard’ (Wee Reference Wee2011:79). This view is in line with Alsagoff's (Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007) Cultural Orientation Model, which characterizes general English use in Singapore as style-shifting across a continuum, between two polarities of the registers of Standard English and Singlish. Thus, English speakers in Singapore can vary the type and frequency of Singlish or Standard English features in their speech, resulting in a variety of styles of speaking or writing (Alsagoff Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007:40–41).Footnote 1 Let us now deal with each of Lee's arguments in turn.

(Mis)alignment of a vernacular with sophistication

The question here is whether the use of Singlish the vernacular (the ‘L’ variety in a diglossic situation; cf. Gupta Reference Gupta and Kwan-Terry1991) in a domain normally reserved for Standard English (the ‘H’ variety) necessarily imparts a ludic quality. The deployment of Singlish in a genre of academic writing is transgressive, but what exactly makes the language use in Spiaking Singlish playful and humourous? Singlish features by themselves have certainly never been described to be innately ludic, so Lee's assumption here appears to be predicated on the idea that it is precisely ‘(mis)alignment’ that makes it so. Such an argument is rather circular. It implies that the register of Singlish is normatively associated with casual and informal settings of communication, and is therefore inappropriate in other more formal domains of use. That is, Singlish use in the academic genre is funny, because it is a priori not supposed to appear in formal writing (and therefore funny when used in such a place). This circularity is problematic as it assumes that the indexical values of Singlish are uncontested and entirely stable.

I would like to interrogate this further by first considering the notion of genre and intertextuality (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin, Emerson and Holquist1981; Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1992; Bauman Reference Bauman and Duranti2001). A genre can imply a communicative event with ‘conventional guidelines to communicative exigencies’ (Bauman Reference Bauman and Duranti2001:80), or that the event constitutes wider, ritualised conventions (Heller & Martin Jones Reference Heller, Martin-Jones, Heller and Martin-Jones2001:9). To Bauman & Briggs (Reference Bauman and Briggs1992),

genre cannot fruitfully be characterized as a facet of immanent properties of particular texts or performances. Like reported speech, genre is quintessentially intertextual. When discourse is linked to a particular genre, the process by which it is produced and received is mediated through its relationship with prior discourse. Unlike most examples of reported speech, however, the link is not made to isolated utterances, but to generalized or abstracted models of discourse production and reception… the creation of intertextual relationships through genre simultaneously renders texts ordered, unified, and bounded, on the one hand, and fragmented, heterogeneous, and open-ended, on the other. (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1992:147, emphasis added)

I concur with Lee (Reference Lee2023) that Spiaking Singlish appears to invoke an academic or scholarly genre of writing, exemplified via a set of paratextual features such as naming the book ‘a companion’ to communication, and alphabetical ordering of entries with a glossary at the end (Lee Reference Lee2023:246). On the one hand, the intertextual link between Spiaking Singlish and a scholarly commentary is made apparent through strategic use of these features that have historically been conventionalized as academic writing. On the other, the deployment of Singlish, conventionally linked to informal and casual communication, would allow the reader to recognize the incongruity between the register and genre it is appearing in. But these are not the only intertextual connections that may be drawn, and such perceived incongruity may even be contested when drawing intertextual links to other Singlish publications and writing. Where Lee and I differ is in the potential interpretations of deploying Singlish in such a genre, the ‘fragmented, heterogeneous, and open-ended’ (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1992:147) nature of intertextuality.

As Lee observes, there are aspects of Spiaking Singlish which are intentionally tongue-in-cheek, for example, the juxtaposition of a Singlish quiz with the A levels. There are also humorous cartoons accompanying every entry of the word or phrase to be explicated. However, as Lee (Reference Lee2023:246) readily admits, these are paratextual features which have nothing to do with the purported humour generated by deploying Singlish features alone. It does not suggest that every aspect of the book, by virtue of using Singlish, immediately undertakes a playful tone. If we were to also understand meaning-making by readers as an agentive process framed and constrained by the potential intertextual links they can make, as well as a ‘condensation’ of an individual's history with ‘physiological, psychological, emotional, cultural and social origins’ (Kress Reference Kress1997:11), then we must also consider the possibility that the types and salience of intertextual links drawn by readers might vary, contingent on an individual's socially framed ‘interest’ at a particular moment in time.

I illustrate this potentiality/contingency of meaning-making with the excerpt below, where Gwee articulates the irony of the Singlish term ‘England’ to refer to the English language.

Through the use of ‘England’, Singlish reminds its speakers that England the language has been a colonial import. England came from England one, and that means through the tok kong British Empire. As a result, while England is now the first language of all schooled Singaporeans, it can neh be our only language, ok? So ‘England’ forces Singlish speakers to see England in both geographical and historical terms and to acknowledge ang moh impact on our part of the world. It insists that we remember what spiaking England well can make us forget, that we dun own the source of this basic feature of us. (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:67)

Even as the publisher of Spiaking Singlish claims that the book is ‘the first language book written entirely in Singlish’ (Gwee Reference Gwee2018:9), Gwee inevitably resorts to Standard English constructions quite extensively throughout, as above. Recall that Singlish is not a ‘fully extensive social language’ (Wee Reference Wee2011:79), and that users can vary the extent of Singlish and Standard English features in speech and writing (Alsagoff Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007). Accordingly, Gwee is seen to vary the frequency of Singlish in the writing, and not every part of the book has the same frequency as the examples proffered by Lee in his article.

In the excerpt above, the potential intertextual links drawn by a reader might not only be about prior academic texts, and how jarring and incompatible Singlish use in this context might appear. It could also connote the seriousness when handling a subject matter like (de)coloniality, a trending topic within the public's collective consciousness (Moosavi Reference Moosavi2020). Arguably, it is the serious connotation of the topic that can be more salient here, compared to the transgressive nature of using Singlish in formal writing. This is why Bauman & Briggs (Reference Bauman and Briggs1992:149) suggest that, ‘Generic frameworks thus never provide sufficient means of producing and receiving discourse. Some elements of contextualization creep in, fashioning indexical connections to the ongoing discourse, social interaction, broader social relations, and the particular historical juncture(s) at which the discourse is produced and received’.

Crucially, Spiaking Singlish ought not be analysed in abstraction, but has to be situated amongst a host of other Singlish publications (including Gwee's own oeuvre) in order to account for meaning-making effects that intertextuality might present. Spiaking Singlish is but one book in Gwee Li Sui's growing number of Singlish publications. Gwee has also translated literary classics including The little prince/The leeter tunku (de Saint-Exupéry Reference de Saint-Exupéry and Gwee2019), and children's books, such as The tale of Peter Rabbit/The tale of Peter Labbit (Potter Reference Potter and Gwee2021) and Grimms’ fairy tales in Singlish: Ten chewren's and household tales (Brothers Grimm Reference Grimm and Gwee2021). Readers of Spiaking Singlish might very well be familiar with these Singlish publications with the potential to draw intertextual links across them, and arriving at very different ideas of how to read Spiaking Singlish apart from just a ludic play at language.

To further demonstrate how a solely ludic sensibility can be quite a limiting way of reading Singlish in an unfamiliar genre, below is an excerpt from the ending of The leeter tunku.

Look carefuly at this scene so that you can recognai if one day you travel to Africa, to the desert. And, if he is laughing, if his hair keem-keem, if he neh answers any questions, you will know who liao. Then zi tong please. Dun leave me sad and alone leh: write to tell me he's back… (de Saint-Exupéry Reference de Saint-Exupéry and Gwee2019:95)

Similar to the previous extract, the salient intertextual link here could include more than the (in)appropriateness of Singlish in a famous literary work. It might be contingent on the reader having read or possessing prior knowledge of previous translations of the book, including other Singlish books such as Spiaking Singlish; the reader might draw links with the preceding plot within the book itself; the topic of the prince's demise might connote somberness, and so on. The point I wish to underline is simple: both excerpts I have provided suggest that the deployment of Singlish per se need not necessitate a solely ludic reading. In both cases, the subject matter at hand (of decoloniality in Spiaking Singlish; of the prince's demise in The leetur tunku), for example, can also demand respective interpretations of serious explication and somberness.

In this light, Lee's (Reference Lee2023:246) overarching claim here that ‘explaining Singlish in Singlish’ would spur ‘laughter for “in-group” speakers “in the know”’, then seems to be a personal metapragmatic evaluation and assumption. This is especially when the claim is not substantiated with empirical evidence (e.g. interviewing readers). I do not dispute that there will be readers who might find the transgressive use of a vernacular in a formal domain humorous. Nonetheless, my discussion of the intertextual connections that can be drawn across texts suggests the possibility that multiple (even conflicting) indexicalities might be found by readers to reside in the text. These possibilities can be seen in the ludic play at addressing decoloniality in Spiaking Singlish, or the presence of both ludic and somber sentiments at the little prince's demise in The leeter tunku.

Defamiliarising Singlish

The second basis of Lee's assertion that Spiaking Singlish is ludic lies in his view that the Singlish features deployed are of such high frequency as to ‘defamiliarise’ the register (Lee Reference Lee2023:245–46). Ergo, Gwee's version of Singlish in the book is not the same as the vernacular used by everyday Singaporeans (Lee Reference Lee2023:253). Beyond the fact that the frequency of Singlish features in the book actually has a fair amount of variability, as seen in the previous subsection, Lee's claim that everyday Singlish is different warrants some investigation.

They say last time only got [Singlish existential verb] Melayu [‘Malay’] and cheena [‘Chinese’] dialects campur-campur [‘to mix’] but no England [‘English’] because people bo tak chek [‘did not study’, meaning had little education]. Lagi [‘even’] worse, they say Singlish only became tok kong [‘potent’] when Singaporeans felt rootless and buay tahan [‘unable to tolerate’] Spiak Good England Movement [‘Speak Good English Movement’].

The passage reproduced here is derived from Lee's abstract of Spiaking Singlish (Lee Reference Lee2023:246). Both grammatical construction of the sentence and much of the lexis can be classified as Singlish.

Let us compare Lee's example with some data from another medium where written forms of Singlish can be found in abundance—the Hardwarezone forum. Founded in 1998, Hardwarezone is an IT-oriented website based in Singapore featuring articles on technology and online forums of various topics. At last count, its forum statistics indicate about 638,000 members, more than 800,000 threads, and almost twenty-nine million individual messages.Footnote 2 Given that Singapore has a resident population (citizens and permanent residents) of four million (Census of Population 2020a), this presumably represents a fairly large proportion of society. The prominence and popularity of the platform has also consistently led engineers to include it as part of a corpus when developing natural language processing models for Singlish (e.g. Hsieh, Chua, Kwee, Lo, Lee, & Lim Reference Hsieh, Chua;, Kwee, Lo, Lee, Lim, Tseng, Katsurai and Nguyen2022; Gotera, Prasojo, & Isal Reference Gotera, Prasojo and Isal2022).

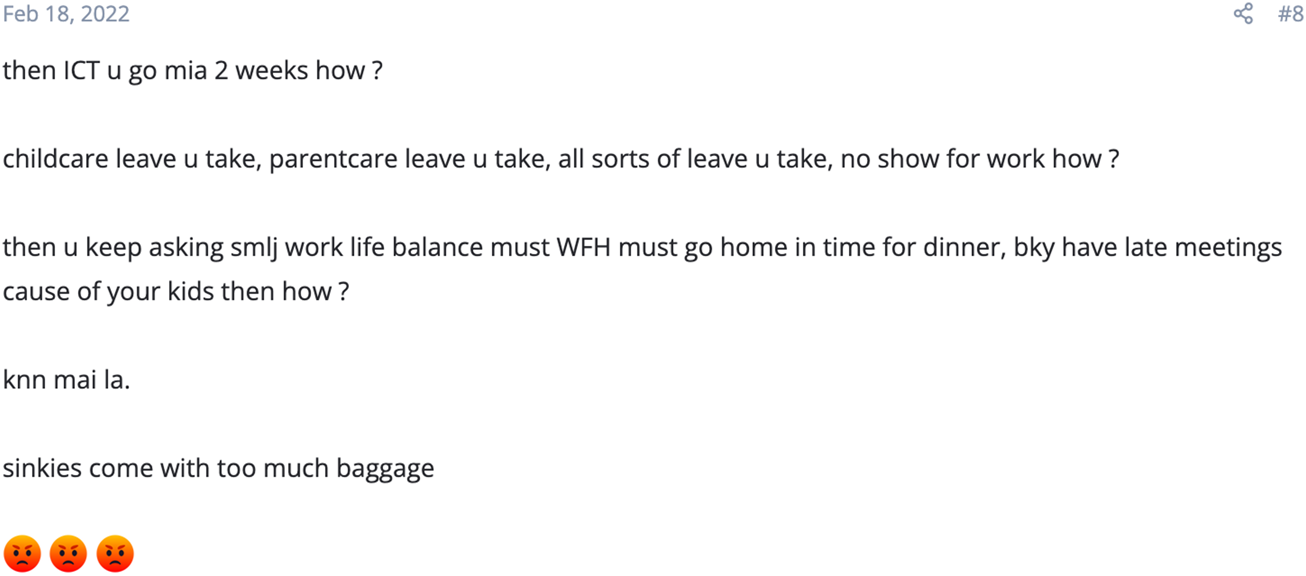

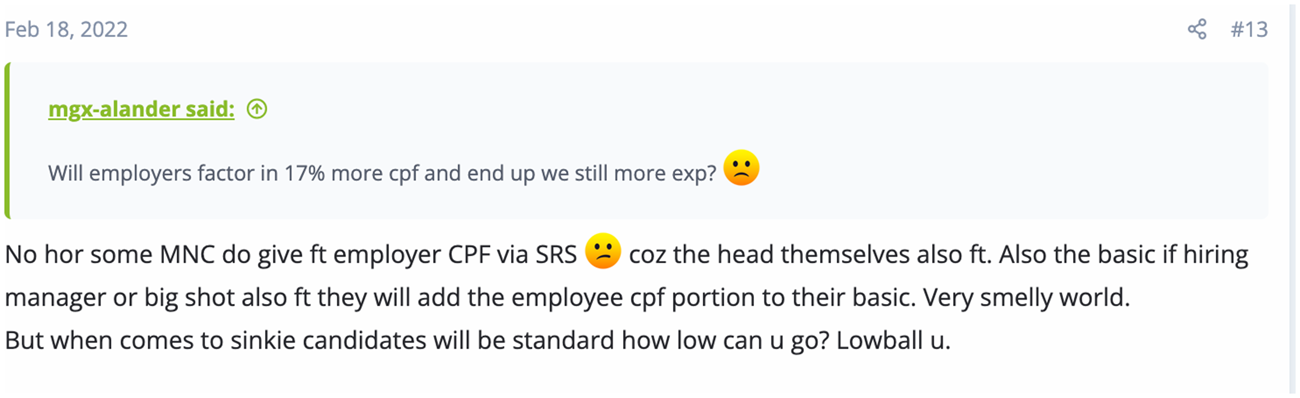

The forum topic here is entitled Will coys hire sinkies if sinkies are cheaper? ‘Will companies hire Singaporeans if Singaporeans are cheaper?’ (Hardwarezone Forums 2022). This is a perennial topic amongst Singapore's labour force, where many citizens perceive excessive immigration as detrimental to their own job prospects. Figures 1 and 2 below show two posts in the same thread in response to the original question.

Figure 1. Post by nyvrem (Hardwarezone Forums 2022).

Figure 2. Post by Sumimasen (Hardwarezone Forums 2022).

As is to be expected, there is quite extensive use of acronyms that is a fairly conventional affordance of online/computer-mediated communication. For example, ‘ICT’ refers to ‘in-camp-training’, a compulsory period when eligible male Singaporean citizens will be called up by the state for reservist training in the armed forces; ‘smlj’ refers to ‘simi lanjiao’, a hokkien vulgarity meaning ‘whatever’ in this context; knn refers to ‘kan ni na’, a hokkien vulgarity meaning ‘fuck you’, but may be used as a discourse particle, as in this case; ‘ft’ meaning ‘foreign talent’, a sociopolitically loaded term in Singapore where anti-immigrant sentiment is rife.

Beyond acronyms, one can also surmise that all sentences are Singlish in grammaticality, with a similarly high degree of heteroglossia in the lexis as Lee's example from Spiaking Singlish. Significantly, such deployment of Singlish is the norm in Hardwarezone Forums. One might analyse these forms to be ‘theatrical’ and ‘hyperbolic’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:246), or as ‘high performances’ signaling pride in Singaporean identity (Wee Reference Wee2018:181). Notwithstanding, these are banal forms of stylization prevalent in everyday discourse, not unfamiliar to a large proportion of Singapore society.

This line of thought also applies to Lee's characterization of gahmen as ‘eye-dialect’, ‘imparting a contingent written form to a word rooted in orality’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:247). In Wee's (Reference Wee2018:180) terms, a word like gahmen might be perceived as a nonce construction—‘marked as deliberate violations of the linguistic conventions associated with Standard English’. But Wee (Reference Wee2018:180) also suggests that whether one regards the word as a nonce construction or not is dependent on whether the feature has become conventionalised or routinized as part of Singlish. In my view, the case of gahmen is a prime example where such conventionalization is emanant, and therefore contested. Using the same platform of Hardwarezone, a quick search for gahmen in its forum pages yields 15,200 entries, the variant gahment yields 21,200 results, while the standard form of ‘government’ yields 96,000 results.

I am not suggesting that the examples from Hardwarezone are exactly the same in quality as Gwee's text in Spiaking Singlish, but am addressing Lee's point that a high frequency of Singlish features in text is ‘defamiliarising’. Consequently, the ‘contingency’ that Lee imputes to the forms of Singlish used by Gwee is highly debatable. This is especially the case when we consider how the entextualisation of Singlish is primarily occurring not through books like Spiaking Singlish, but via mundane communication in the ubiquity of online forums and instant messaging platforms, by a populace increasingly dependent on such technology. Collectively, as a social practice, this means that there is and will be substantial and substantive conventionalization of spelling of Singlish. Spiaking Singlish is not comprised of novel inventions of Singlish orthography and morphology, with a frequency that is necessarily alien compared to common usage. It draws on existing Singlish forms and practices already in use and entextualised by other ordinary users before Gwee on an everyday basis.

The discussion thus far has tried to demonstrate that the ludic quality in Spiaking Singlish is but a narrow interpretation. Moreover, the forms of Singlish use in the book is arguably one that is banal, emergent, and widespread, rather than a variant completely unfamiliar to most Singaporeans. My argument, through examples of potential intertextual connections, suggest multiple indexicalities (beyond just a ludic quality) residing in Spiaking Singlish. Instead of this rigid and narrow form of enregisterment denoted by Lee, the next section attempts to highlight enregisterment as a diachronic process that is in flux, and therefore potentially transformative.

ENREGISTERMENT AND SEDIMENTATION

Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2016:641) reminds us that, ‘Not every description of a process of enregisterment has to describe every aspect of the process, but we should be aware of the complexity and contingency of the process and avoid the temptation to assume that meanings are more shared and stable than they are’. In depicting a narrow interpretation of Spiaking Singlish, Lee (Reference Lee2023) appears to present the book's enregisterment of Singlish as a stable and uncontested process. I would like to emphasise the diachronic aspect of enregisterment, and address its implications for how we might perceive and situate Spiaking Singlish.

In Agha's (Reference Agha2007:81) words, ‘enregisterment’ refers to ‘processes and practices whereby performable signs become recognized (and regrouped) as belonging to distinct, differentially valorized semiotic registers by a population’. Parsed by Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2016:633), this means that registers stabilize into named entities via sociohistorical processes, when people orient to a particular set of linguistic forms in specific contexts, allowing that set of linguistic forms to be identified as a register. Thus, an indexical relationship between a linguistic form and meaning (such as Singlish being linked to informality) can be perceived as a snapshot (static) view of an ongoing fluid process of enregisterment. To be sure, this diachronic understanding of enregisterment is not new. Johnstone (Reference Johnstone2016:638), for example, points to how the same linguistic form might be enregistered in multivariate ways, to different individuals in the same locality, at different historical times. That is, the social meanings associated with the form can be different and change with time.

But what is it that allows such different, even conflicting enregisterment processes to take place? Pennycook's (Reference Pennycook2004) reading of Butler and Bourdieu has been immensely helpful in this regard. In theorizing the notion of performativity, Butler critiques Bourdieu's ‘conservative account of the speech act’ (Butler Reference Butler1997:142 in Pennycook Reference Pennycook2004:12). For Bourdieu, the power of discourse lies ‘in the institutional conditions of their production and reception’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991:111). But Butler argues that such a view implies a ‘static and closed system’ of language use, where utterances are ‘mimetically related’ to the social positions of individuals. That is, ‘performative utterances are only effective when they are spoken by those who are (already) in a position of social power to exercise words as deeds’ (Butler Reference Butler1997:156). A straightforward example: the power (and meaning) of a police officer uttering ‘you are under arrest’ is directly related to his/her position as an executive of the law.

Butler asserts that Bourdieu disregards Derrida's discussion of context and the power of words through the notion of ‘iterability’ (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2004:12), where repetition of discursive formations need not be a static process of replication. Instead, repetition can involve change by contravening an original context and establishing new contexts, and hence new meanings (Milani Reference Milani, Mar-Molinero and Stevenson2006:115). For example, a child shouting ‘you are under arrest’ in a game of tag. This sense of repeated discursive acts contributing to ever new forms of meaning is especially crystalised in the metaphor of ‘sedimentation’ that Butler (Reference Butler and Shusterman1999) adopts. Pennycook compares the congruence of this metaphor between Butler's (Reference Butler and Shusterman1999) argument for performativity and Hopper's (Reference Hopper and Tomasello1998) own use of the term in describing the ostensible stability of language systems.

just as Butler (Reference Butler and Shusterman1999) argues that identities are a product of ritualized social performatives calling the subject into being and ‘sedimented through time’ (p. 120), so for Hopper ‘there is no natural fixed structure to language. Rather, speakers borrow heavily from their previous experiences of communication in similar circumstances, on similar topics, and with similar interlocutors. Systematicity, in this view, is an illusion produced by the partial settling or sedimentation of frequently used forms into temporary subsystems’ (pp. 157–158). (Pennycook Reference Pennycook2004:14)

In this way, the social meanings that speakers come to attach to particular registers can similarly be seen as a cumulative sedimentation of acts repeated over time. While this might be regulated or constrained by the genre and contexts in which discourse production takes place, there is at the same time, the possibility for new meanings to emerge when the contexts of discursive production change (i.e. iterability). Consequently, this shifts the focus and understanding of language from being a mere reflection of social categories, such as age, class, education, gender, and so on, to one where language is also generative of these aspects of identity (Milani Reference Milani, Mar-Molinero and Stevenson2006:105).

As Pennycook (Reference Pennycook2004:15) recognises, the metaphor of sedimentation is also aligned with Bakhtin's sense of intertextuality. It is at this point where it might be useful to apply the idea of sedimentation to the situation of Singlish and Spiaking Singlish. It is worth returning to Bauman & Briggs’ (Reference Bauman and Briggs1992:149) discussion of genre and intertextuality.

On the one hand, texts framed in some genres attempt to achieve generic transparency by minimizing the distance between texts and genres, thus rendering the discourse maximally interpretable through the use of generic precedents. This approach sustains highly conservative, traditionalizing modes of creating textual authority. (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1992:149)

This ‘minimizing’ of texts and genres can be exemplified by a text like this very academic article, which has to adhere to strict rules of style, formatting, rhetoric, and register.

On the other hand, maximizing and highlighting these intertextual gaps underlies strategies for building authority through claims of individual creativity and innovation, resistance to hegemonic structures associated with established genres, and other motives for distancing oneself from textual precedents. (Bauman & Briggs Reference Bauman and Briggs1992:149)

This is what Spiaking Singlish appears to be doing. I agree with Lee (Reference Lee2023:250) that the book is in effect resisting and undermining hegemonic state discourse regarding Singlish as an ‘aberrant’ form of speech, associated with the lowly educated. In entextualising Singlish in an unfamiliar context of scholarly writing, the book is a demonstration that Singlish can be used to write extensively, coherently, and meaningfully—without need to always descend into crass humour.

Repeated productions and entextualisations of similar ways of writing, through Spiaking Singlish and other publications in the domain of scholarly works, and through everyday conventionalisation via online forums and instant messaging, would inevitably contribute to the very processes of sedimentation highlighted above. Seen in this light, any comprehensive picture of the enregisterment of Singlish cannot be limited to an analysis of Spiaking Singlish. The book is but a more recent example of the enregisterment of Singlish in written form, that can be traced to early publications such as Eh, Goondu! by Sylvia Toh Paik Choo in 1982.

There is also a need to account for changes to the wider sociohistorical contexts surrounding Singlish. Singlish use was once sanctioned on state media, both in print and broadcast. The oft-cited example is of Phua Chu Kang (Wee Reference Wee2014), a fictional character in a popular local sitcom in the 1990s, who only spoke Singlish. This led to the programme being publicly censured by then Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong in his National Day Rally Speech in 1999, accusing Phua Chu Kang of popularizing Singlish to the detriment of Standard English. Producers of the sitcom then had to write it into the story for Phua Chu Kang to attend English ‘upgrading’ lessons to improve his speech. The situation has since changed dramatically over the course of two decades. Singlish is now prevalent in corporate advertising, state information campaigns, and National Day Parades. These were all domains and genres where Singlish was not permitted and widely seen by the state and public to be inappropriate.

The point here is that any perceived incongruity between Singlish and the formal domain is being contested and continually destabilised by shifting contexts in which the entextualisation of Singlish occurs. Because of such changing contexts of use, the meanings enregistered with Singlish are also constantly changing and will change, with the added complexity that different social groupings of various ages might enregister Singlish differently. The increasing prevalence of Singlish in the lives and social practices of Singaporeans, especially the younger generation, may have culminated in changing and differential forms of enregisterment and attitudes towards the register. In allusion to this, a national survey conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies (Mathews, Tay, Selvarajan, & Tan Reference Mathews, Tay, Selvarajan and Tan2018:94) uncovered that only twenty-four percent of respondents aged eighteen to twenty-five felt that it is ‘never appropriate for teachers to use Singlish during lessons in school’, compared to fifty-three percent of respondents aged over sixty-five. This again challenges the validity and typicality of Lee's narrow reading of Spiaking Singlish as only ludic and elitist.

If we were to take up the idea that enregisterment is a shifting process in line with sedimentation, then Lee's (Reference Lee2023) characterisation of the enregisterment of Singlish appears to be a synchronic and static view of language use. In this view, Singlish the register appears unconditionally linked with informality, so that its use in an academic genre can only evoke a ludic reading. Instead, I argue for a more complex and diachronic iteration, where there can be a range of potentialities to how Spiaking Singlish might be interpreted by readers today and in the future, without presuming that Singlish is a priori incompatible with formal discourse. This is with the implication that the book is contributing to the potential transformation of social meanings associated with Singlish in the public sphere.

THE MONOLECTAL SINGLISH USER

The third pillar to Lee's overarching claim that the form of Singlish in Spiaking Singlish is elitist lies in his configuration of a large segment of Singapore society who are ‘monolectal Singlish users’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:243). To be sure, Lee is not the only scholar to refer to such a grouping. For instance, Wee's (Reference Wee2018) discussion of the ‘monolectal singlish user’ is as a social grouping implied in and originating from state discourse. While Wee does not question the existence of such a group, he does not state it as a sociolinguistic fact either. He uses another term, the ‘Singlish subaltern’, to make his primary argument that there is a marginalised group (with lower proficiency in Standard English) who have less participatory access to public discourse and debates about Singlish.

In the context of the Singlish controversy, the monolectal Singlish speaker—the speaker whose English repertoire is publicly characterized as being limited only to Singlish (in the sense of ‘broken English’) and who therefore lacks the facility to switch between Singlish and Standard English—has the status of a subaltern. Despite being implicated in the controversy, this is the figure that need not and is not expected to directly speak to the issues that have been raised by the presence, spread and popularity of Singlish. There is no expectation that such an individual might have the capacity to contribute in any meaningful way to the Singlish controversy. The plight of the subaltern monolectal Singlish speaker, as we now see, is represented only indirectly via anecdotes and stories about his or her presumed linguistic difficulties and travails. (Wee Reference Wee2018:99–100)

More than referring to a group who might have less access to representation, Lee goes further in detailing particular traits of the ‘monolectal Singlish user’:

(i) These speakers ‘have little or no access to a comprehensive repertoire of Standard English due to, inter alia, relative lack of education’ (Lee 2018:243). They have little capacity to ‘codeswitch’ between Singlish and Standard English (2018:259).

(ii) These speakers are ‘socially and geographically immobile’ (2018:250, 257).

(iii) These speakers only operate at the first order of indexicality, that is, they do not recognize their speech as a variant form of English (2018:250); a few of them might recognize Singlish as linked to local identity at the second order of indexicality (2018:250, 259). Conversely, they are completely incapable of harnessing Singlish as a resource to resist or challenge dominant discourses of Singlish as ‘aberrant’ (2018:250, 258).

In order to examine these assumptions, I attempt to answer the following sets of questions in the proceeding subsections.

(a) Who exactly are these lowly educated, socially immobile people who can only speak Singlish? How many of them are there in Singapore society? Are they monolingual? Can we not have sophisticated/cosmopolitan multilingual speakers who happen to have a lower proficiency in Standard English?

(b) Does having a lower proficiency in Standard English immediately imply that one is speaking Singlish? Is codeswitching between Singlish and Standard English an ability limited to an elite group in Singapore?

(c) Is the lectal continuum (first posited by Platt in 1975) still an accurate/useful way to characterise Singlish use in Singapore?

Searching for the ‘monolectal Singlish user’

The exploration of census data below is with two caveats. First, given the lack of an ethnographic study of individuals who might be monolectal, it is difficult to say for certain if such individuals exist or not. In relying on census data, I am simply interrogating Lee's notion of the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ as a hypothesis (for the sake of argumentation), not claiming that they do exist. Second, the census data is useful to demonstrate the complex intersectionality of class and multilingualism in Singapore, which challenges any rigid link between social class and a given language variety (that Lee's monolectal denotation purports).

Singapore has a resident population (citizens and permanent residents) of about four million, comprising three official racial groupings of Chinese (74.3%), Malays (13.5%), and Indians (9.0%) (Census of Population 2020a:ix). Since independence in 1965, the state has promulgated a bilingual policy where students in all state-run schools have to learn English and their prescribed Mother Tongue associated with their official race (i.e. Chinese/Mandarin for the Chinese; Malay language for the Malays; Tamil or another permitted Indian language for the Indians). The diverse linguistic milieu is hence one where the vast majority of individuals are multilingual speakers—if not literate (in the traditional sense) in more than one language, then having possession of a multilingual ‘repertoire’ (Blommaert & Backus Reference Blommaert, Backus, Saint-Georges and Weber2013). I use ‘repertoire’ here in the manner denoted by Blommaert & Backus (Reference Blommaert, Backus, Saint-Georges and Weber2013:21), where the individual's linguistic resources might range ‘from “full” active and practical competence’, to ‘bits of language(s)… just recognizable emblems of social categories and spaces’. In evidence of this phenomenon, out of a resident population of 3.6 million aged five and above, 80% reported using at least two languages (including vernaculars) at home (Census of Population 2020a:viii).

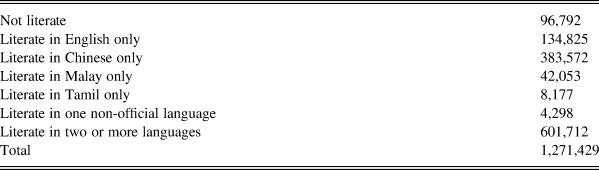

I first focus on Lee's (Reference Lee2023) assumption here that the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ lacks education (Lee Reference Lee2023:243), and is ‘socially and geographically immobile’ (Lee Reference Lee2023:257). Such a person might most likely reside amongst the population who are completely illiterate, or literate in only one language and has had a low level of education. A more generous estimate can also encompass individuals who are literate in two or more languages, though this is with the caveat that the more languages one is competent at, the likelier one will have more cosmopolitan orientations (cf. Alsagoff Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007:39). This might include people who report being literate in English, given that (according to Lee Reference Lee2023:250) they might (mis)recognize their form of language use to be Standard. As a benchmark for lower levels of education, I exclude those who have attained educational qualifications beyond the secondary school level (i.e. only those with secondary education and below are counted). Table 1 above summarises these numbers.

Table 1. Resident population aged fifteen and above by language(s) literate in, with at most secondary school education (adapted from Census of Population 2020a:145–46).

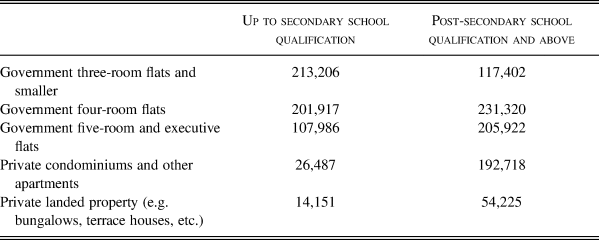

So, depending on how conservative one's estimates are, the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ could be found in 20% (if one only counts those who are illiterate or literate in only one language) to 40% of the resident population aged fifteen and above (out of a total of 3.14 million) (Census of Population 2020a:145). However, education is but one indicator of social mobility and potential for a globalist outlook. Another, perhaps, surer marker of wealth and class in Singapore is in the type of housing one lives in.Footnote 3 In Singapore, 77.9% of the population lives in government-built housing,Footnote 4 which are priced much cheaper compared to privately built housing.Footnote 5 It is worth looking at the relationship between housing type and education attained (see Table 2).

Table 2. Number of households by type of dwelling and highest qualification attained within the household (excluding those who are current students); adapted from Census of Population 2020b:65.

While there is obviously a positive co-relation between education attained and type of housing one lives in, there is also a sizeable proportion of individuals who cannot be claimed to be socially immobile despite a lower level of education. 350,541 of such lower educated households live in at least a government-built four-room flat (the median government flat type). This accounts for 25% of all 1.37 million households in Singapore, and 62% of all 563,747 households whose highest educational attainment is at secondary school level.

This suggests that the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ who lacks education, and who is purportedly ‘socially and geographically immobile’ can be found in at most 15% of Singapore's total resident population (i.e. 38% of the population with at most secondary school education). This figure of 15% is over-represented by those aged fifty-five and above, and can be expected to decrease with time since 90.1% of residents aged twenty-five to thirty-four have attained post-secondary or higher qualifications (Census of Population 2020a:17).

Lee's (Reference Lee2023:243) dichotomy of ‘monolectal Singlish users’ and the other group comprising ‘highly educated individuals… who have the capacity to switch easily between Singlish and Standard English… hence able to deploy linguistic features conventionally associated with Singlish for identity work on metadiscursive scales’ therefore appears to be rather reductionist and misleading. It oversimplifies the complex intersectionality across an individual's (multi)lingual practices, (multi)cultural orientations, and his/her supposed social class, and overstates the scale and significance of an uneducated and immobile class. In the context of a culturally diverse society with multilingualism as the norm, where social mobility need not always cohere neatly with educational levels, it is not inconceivable for an individual to have a lower proficiency in Standard English, and yet still engage in cosmopolitan and globalist practices through other languages and repertoires.

Further, even if one can only speak Singlish, why does this mean that the individual has no capacity for metalinguistic awareness nor cognitive functions that allows him/her to resist, negotiate, challenge hegemonic discourses surrounding Singlish in their own lives (i.e. the third order of indexicality in Lee Reference Lee2023:250)? They may be less able to participate in public discourses about Singlish (most of which is conducted in and regulated through Standard English), but being voiceless does not equate to being thoughtless. As has long been argued elsewhere, literacies (Street Reference Street1995) and language competencies (Blommaert & Backus Reference Blommaert, Backus, Saint-Georges and Weber2013) need not be defined strictly nor acquired only via traditional forms of schooling and institutional knowledge. Lee's (Reference Lee2023) delineation of the lowly educated ‘monolectal Singlish user’ mired in their circumstances is one that requires explicit research and evidence, especially because the claim is extraordinary. At this point it remains no more than an essentialist and demeaning caricature.

On lower proficiencies of English and codeswitching

In further interrogating Lee's (Reference Lee2023) stated traits of the ‘monolectal Singlish user’, there is also a need to consider two coterminous language practices (not) ascribed to the group. First, the implied idea that these individuals with lower proficiencies in Standard English are necessarily speaking Singlish. And second, that the ability to switch between Standard English and Singlish is a ‘privilege’ limited to the highly educated (Lee Reference Lee2023:259), a view completely aligned with the state's (Chang Reference Chang2016).

As it happens, both phenomena might be (in)validated through recent applied linguistic research about the pedagogical value of Singlish in the Singapore ELT classroom. Lu (Reference Lu2023a, Reference Lub) conducted a bidialectal progamme involving Standard English and Singlish in a mainstream secondary school targeting thirteen-year-old Secondary One students. The programme allowed students to use Singlish as a linguistic resource in classroom discussions and written tasks, in order to investigate if they might be confounded in their learning of Standard English, and to see if students might be able to deploy Singlish/Standard English appropriately. Lu's (Reference Lu2023a:332–33) choice of fieldsite and participants (i.e. not top-performing elite students) were also intentional in trying to examine the veracity of state discourses regarding individual competencies in distinguishing and utilising both registers.

In one particular classroom activity, students were tasked to produce a poster advertisement for specific products. Lu (Reference Lu2023a) found that students had a patterned way of utilising Singlish and Standard English features according to the genre of writing (e.g. tagline vs. terms and conditions in a poster), as well as the type of product to be advertised and register that ought to be associated with it (e.g. fast food and Singlish). To Lu (Reference Lu2023a:345), this regularity indicated that these students were well aware of ‘(a) indexical links between notions of social class and branding, (b) purpose of communication, (c) audience design, (d) genres of writing, and the appropriate registers of Singlish/Standard English in relation to all of these abstract and interrelated communicative concepts’.

Even as some of these students portrayed lower proficiencies in English, any ‘errors’ made in writing were found not to be formal Singlish features (particularly because there was no regularity to these mistakes), but a confusion of specific Standard English syntax (Lu Reference Lu2023a:343). In fact, students were also shown to make mistakes when deploying Singlish, for example, misspelling the word ‘chop’ (meaning to literally ‘stamp’ or affirm) as ‘chope’ (meaning to reserve) (Lu Reference Lu2023a:342).

Lu (Reference Lu2023a:346–47) thus concludes that,

None of the completed posters contained texts where the boundaries between Singlish and Standard English features were mixed and unclear (the heart of the state's fears). This paper has provided direct evidence of the linguistic capabilities of the average Singaporean student in distinguishing and deploying both registers meaningfully, capabilities that are not limited to the elite minority.

These findings are further corroborated in the IPS national survey (Mathews et al. Reference Mathews, Tay, Selvarajan and Tan2018:56–57), where more than 75% of respondents aged eighteen to twenty-five reported speaking Singlish ‘well’ or ‘very well’, and among them, 95% reported also speaking Standard English at least ‘well’.

For the purposes of my argument, Lu's (Reference Lu2023a) study also demonstrates that the linguistic performance of individuals with lower competencies in Standard English does not always mean they are producing Singlish. Failing to adhere to Standard English rules of syntax is not the same as using regular Singlish features. This can connote that such individuals are aware of a variant form of English (the second order of indexicality according to Lee Reference Lee2023:250), and are attempting to reach for the Standard variety in their linguistic production, albeit not always successfully.

Thus far, I have argued that Lee's depiction of the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ fails to account for complexities in the average Singaporean's multilingual repertoires and possibility of being socially mobile in spite of lower education levels. It assumes, without basis, that the ability to switch between Singlish and Standard English is the reserve of the highly educated elite; and that being only capable of producing Singlish, such speakers tend not to be aware of variant English forms. In citing recent research on learners who are non-elite individuals, I have shown that such assumptions appear misplaced. This then leads me to question the value of the lectal continuum in characterising Singlish use in Singapore today.

The lectal continuum

The influence on Lee's use of the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ may be traced to Platt's original formulation of the Lectal Continuum Model in 1975 (Tan Reference Tan2023:7). Platt (Reference Platt1975:363) saw Singlish as a ‘non-native’ variety of English, ‘acquired by some children before they commence school and to become virtual “native” speech variety for some or all speakers’ (Platt Reference Platt1978:55). He labeled Singlish a ‘creoloid’ or ‘basilect, with ‘Acrolectal Singapore English’ being very similar to Standard British English in syntax. To Platt (Reference Platt1975, in Tan Reference Tan2023:8), ‘Singlish is a product of imperfect learning and spoken only by the uneducated and uncouth’. Significantly, he makes a clear link between social class with the type and number of lects available to the speaker, stratifying society into upper, middle, and lower classes. A speaker with higher socioeconomic status has access to the acrolect as well as Singlish as a colloquial variety. Nonetheless, this speaker's form of Singlish is still positioned higher on the continuum than the formal speech of another speaker of lower socioeconomic status (Tan Reference Tan2023:7–8).

This assumption of the rigid link between lects and social class is a primary reason why the model was seen as unsatisfactory by Gupta (Reference Gupta and Kwan-Terry1991) (Tan Reference Tan2023:8). Both Gupta (Reference Gupta and Kwan-Terry1991) and Alsagoff (Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007) acknowledged the fluidity of social class and range of Singlish features that supposed individuals in the upper classes might produce. That is, persons of higher socioeconomic status might well produce the same Singlish features and constructions as those from the lower classes. This is why Gupta (Reference Gupta and Kwan-Terry1991) proposed a diglossic framework, while Alsagoff (Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007) sketched the Cultural Orientation Model. In particular, Alsagoff (Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007) critiqued the Lectal Continuum as such:

the model imposed upon Singlish the label of ‘undesirable’, since it is implied that the use of Singlish is not borne out of choice but of a lack of education. The lectal continuum model also clearly marks Singlish as undesirable, associating it with low economic status. (Alsagoff Reference Alsagoff, Vaish, Gopinathan and Liu2007:27)

Lee's denotation of the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ thus appears strikingly similar in the intransigent connection he draws between a lack of education, social mobility, and a figure who can only speak Singlish. Further, the pragmatics of using Singlish by the educated classes may not be in the way described by Lee (Reference Lee2023:250), where ‘Those features are activated in speech to tactically perform social work, as when acrolectal speakers of English deliberately shift into a colloquial register to index distance from the cosmopolitan and camaraderie with the heartlander’. Instead, as evidenced in ethnographic research of top-performing students from an elite school in Singapore (Lu Reference Lu2021:162), Singlish would be used in an unmarked and mundane manner among themselves, not just to ‘condescend’ (Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1991:69) to the level of individuals less proficient in Standard English.

The lectal continuum is a model fixated on social class and its supposed links to (meta)linguistic competence and awareness. As has already been addressed in previous sections, it cannot account for the multilingual repertoires of Singaporeans whose linguistic practices often transcend socioeconomic indicators. It is a model no longer fit for purpose. Lee's (Reference Lee2023) reliance on the model is similarly mistaken. It begs the question of who the elitist truly is, out of touch with sociolinguistic realities and defining exclusionary language practices. Ultimately, if we were to recognize that the boundary between Singlish and Standard English is porous and difficult to ascertain, and more a matter of discursive construction (cf. Leimgruber Reference Leimgruber2012, Reference Leimgruber2013), then it might never be possible to identify an individual as truly monolectal.

CONCLUSION

In sum, Lee (Reference Lee2023) paints a picture of a substantial group of hapless, lowly educated Singlish speakers, who are socially immobile due to the linguistic capital they do not possess. Correspondingly, these are individuals with little metapragmatic sense of nor use for Singlish in the construction of their own cultural identity. In addition, Lee offers a synchronic and static view of enregisterment. In this paradigm, Gwee's transgressive work (i.e. Spiaking Singlish) in trying to enregister Singlish in more formal domains can only be read in a ludic sense. Spiaking Singlish should thus be perceived as elitist and excluding these ‘monolectal’ individuals.

Through an exploration of census data and applied linguistic research, this article argues for an alternative reading of the situation, where the ‘monolectal Singlish user’ is an imaginary ungrounded in evidence. In producing and therefore perpetuating such ‘lectal’ discourse without empirical basis, Lee appears to move in a narrow, classist circle of his own imagining. Importantly, I argue through the notions of intertextuality and sedimentation that Spiaking Singlish may be read in alternative ways, and therefore be situated in a diachronic process of enregisterment, contributing to new social meanings that may be attached to Singlish in an unfamiliar genre.

Bourdieu reminds us that there needs be a certain level of reflexivity when undertaking research work and writing.

The sociologist is thus saddled with the task of knowing an object—the social world—of which he is the product, in a way such that the problems that he raises about it and the concepts he uses have every chance of being the product of this object itself. (Bourdieu & Wacquant Reference Bourdieu and Wacquant1992:235)

This is not to say that this article is immune to issues of subjectivity. But I hope that in anchoring my claims in evidence and the investigative work of others, I have situated my arguments within a paradigm of greater rationality and clarity. As Mehan (Reference Mehan, Wetherell, Taylor and Yates2001:360) was acutely aware, ‘When discourse is viewed as activity that culturally constructs clarity out of ambiguity, then we should not be surprised to find multiple modes of representation’. Significantly, history itself is replete with successive attempts of imposing one mode of representation over others (Mehan Reference Mehan, Wetherell, Taylor and Yates2001:361). In the case of Lee (Reference Lee2023) and this rejoinder, it is for the learned reader to decide which representation is more convincing.

Finally, I agree with Lee (Reference Lee2023) and Wee (Reference Wee2018:94–117) that there are Singlish speakers who have less voice, and are less able to participate in and shape public and, especially, academic forms of discourse. My point is that academic discourse and debate ought to bear a higher responsibility in representing these subjects—to investigate their actual practices and characteristics rather than assuming them. Uncritically agreeing with and reproducing circulating discourses about these speakers is not being responsible.