INTRODUCTION

The African-honed expertise that enslaved underwater divers carried throughout the Atlantic world allowed them to quickly recover several tons of gold, silver, and other items from shipwrecks, especially old Spanish treasure hulks. Possessing proficiencies held by few in the world, divers exchanged their unique ability to rapidly produce capital for semi-independent lives of privileged exploitation. Most were hired from their owners and treated like free, highly skilled, craftsmen, receiving both wages and equal shares of salvage, enabling some to purchase their freedom and that of family members. Even as terrestrial bondage compelled captives to spend the majority of their day toiling for slaveholders, aquanauts dove less than two hours per day and performed no other substantial work while salvaging. Divers were not motivated by coercive discipline. Instead, white salvagers cultivated a sense of mutual obligation arising from collective responsibilities, material rewards, and other circumstances, convincing divers to cooperate and conspire with them to salvage and smuggle recovered goods into homeports.Footnote 1

By considering seaports’ relationships with coastal seas “History Below the Waterline” integrates the ocean into Atlantic history and African immersionary traditions into maritime history. This article follows salvage divers deployed from seaports throughout the Atlantic world to nearby and far-off shipwrecks that served as hinter-seas of economic production. Scholars typically situate seaports between hinterlands and overseas markets, assuming colonial economies pivoted on rural production. This article shifts our intellectual focus seaward to consider how salvage divers harvested others’ misfortune from the seafloor to produce capital that helped finance terrestrial production throughout the British Empire.

SEAS OF POSSIBILITIES

Scholars have documented how coastal waters served as hinter-seas of economic production for those daring enough to ply them while fishing for fined fish, shellfish, and whales. Thousands of ships sank in the western Atlantic, providing opportunities for salvagers who, in early modern vernacular, “fished” upon wrecks. The shallow, coral-toothed shipping lanes encompassing Caribbean and Bahamian islands were well-traveled, tricky, and dangerous to navigate, making them fertile hinter-seas.Footnote 2

Most shipwrecks occurred in coastal and inter-island waters, after a vessel struck a reef, coming to rest in waters thirty to seventy feet deep and often relatively close to port. Diving deeper than about twenty-five feet presents increasingly greater challenges. For instance, as one descends, mounting water pressure increasingly hurts the divers’ ears. At sixty feet, the air in the divers’ lungs is compressed, creating negative buoyancy, causing their bodies to sink rather than float.Footnote 3

Aquanauts were adept at what is now called freediving, or diving with only the air in one's lungs. Freedivers spent years honing their minds and bodies to meet underwater challenges, a process beginning during youth. Medical research suggests the physiology of enslaved freedivers adapted to repeated prolonged submersion, water pressure, and oxygen apnea by, among other things, slowing their metabolism, enabling them to more efficiently consume oxygen, and sharpening underwater vision up to twice the normal range.Footnote 4 Pieter de Marees, a Dutch merchant-adventurer who traveled to Africa's Gold Coast and ostensibly the Caribbean during the 1590s, seemingly reported on this, saying Africans “can see underwater”.Footnote 5

Freedivers learn to pressurize their ears and breathe effectively. Many inhale and exhale deeply several times to expand their lung capacity and oxygenate their blood before taking one deep breath. During descents, they must equalize their middle and inner ear with surrounding water pressure by letting air into the Eustachian tubes, otherwise their eardrums can rupture, which can cause disorientation and drowning.Footnote 6

Composure precluded the release of oxygen-depleting adrenalin as freedivers coped with variables in water pressure, temperature, and visibility. Surge (the underwater effects of oceanic forces pushing water into shallows) thrust divers shoreward then pulled them seaward, while prevailing currents, wind patterns, and far-off storms produced stratified flows that moved in diverse directions at different depths, creating a perplexity of forces. Divers calculated these forces by feeling the movement of their body and observing the motions of boats, fish, and submarine vegetation.Footnote 7 They similarly remained calm when entering wrecks and encountering sharks, with one observer noting that “Each [Key Wester] vessel has a diver, who will go into the cabin of a ship, or to the bottom of the sea, if not over six fathoms [thirty-six feet] deep”. Divers seemingly understood that most shark species did not pose a risk to humans, prompting one traveler to write that Bahamians “appear to have little dread of sharks”.Footnote 8

Making one dive every five to ten minutes, salvagers worked from morning until about noon, when winds made conditions rough. Most could hold their breath for about two or three minutes, a rare few four minutes. One Bahamian boasted, in 1824, that he “has among his slaves divers who can go to depths of sixty feet & remain under water from two to three minutes”.Footnote 9

Spanish policies precipitated numerous shipwrecks. Spain forced Amerindians and enslaved Africans to mine precious metals, amassing these commodities, along with Asian goods, in Havana. Annual treasure fleets departed for Europe during late summer and fall, sailing through the shallow reef-encrusted Bahamas and Florida Straits during hurricane season, causing many shipwrecks (Figure 1).Footnote 10

Figure 1. The above maps illustrate the location of the shipwrecks discussed in this article: the Mary Rose, the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, “Bahama Wrecks”, and the Hartwell. Also shown is Arguin Island, which is reportedly where the Mary Rose salvage divers were from.

Wreck locations were written upon the lips of merchants, fishermen, and sailors, who saw masts protruding from the depths or dark hulks silhouetted against white sands beneath clear Caribbean waters. Verbal accounts of shipwreck survivors, sometimes passed down through the years, disclosed the location of others. These whisperings inspired treasure hunters to cruise rumored waters, dragging grappling hooks across the seafloor, and sending down divers to investigate when something was snared or promising objects spotted.

Salvagers immediately worked recent wrecks, before oceanic forces broke them apart and scattered them. Older hulks were typically salvaged from spring through fall, when seas were calm and underwater visibility good, making operations safer and easier. Wills, estate inventories, runaway slave advertisements, auction notices, and other documents indicate that most English seaports, from Barbados to Virginia, were home to a few divers who were owned by slaveholding mariners and waterside planters. At any given time, perhaps 500 experts regularly worked as salvage divers. Divers were usually owned by several different slaveholders who brought them together to form teams of two to six aquanauts and a few enslaved apprentices.Footnote 11

Salvagers operated along an ill-defined border separating legal activities from piracy. Maritime laws stipulated that shipwrecks remained their owners’ property, requiring salvagers to gain permission to work them or turn over salvage to shipowners or government officials, usually receiving twenty-five per cent of the value of what they recovered. Piracy is an act of robbery at sea and wrecking is a particular type of piracy. Some salvagers became wreckers by working hulks without permission. English officials usually only enforced salvage laws when it came to English and ally vessels, requiring salvagers to pay the crown a “royal tenth” of proceeds for permission to plunder Spanish wrecks. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, after the known Spanish treasure wrecks were stripped, salvagers increasingly wrecked English vessels.Footnote 12

GAINING PRIVILEGES IN THE DEEP

Privileges hinged on divers’ ability to use African expertise to produce significant capital for enslavers. Slaveholders understood that members of certain African ethnic groups possessed knowledge and skills suited to specific labor demands.Footnote 13 Sources suggest that seventeenth-century salvage divers, like most slaves at the time, were African-born and that their skills were developed in African waters. Early travelogues documented how Atlantic Africans, particularly Senegambians and Gold Coast people, incorporated swimming and underwater diving into their work and recreational lives, alerting slaveholders to the possibilities of exploiting Africans’ aquatic proclivities. Coming from societies that had largely abandoned swimming during the medieval period, European travelers were impressed by Africans’ swimming and underwater diving abilities. In 1455, Venetian merchant-adventurer Alvise de Cadamosto observed two Senegambian swimmers negotiate storm-swept seas to deliver a letter to his ship “three miles off shore”, proclaiming that those living around the Senegal River “are the most expert swimmers in the world”. During the 1590s, De Marees observed that Gold Coast Africans “can swim very fast, generally easily outdoing people of our nation in swimming and diving”, while Johann von Lübelfing expressed that Ivory Coast people “can swim below the water like a fish”.Footnote 14 European shipwreck survivors reported that African rulers claimed wreckage within their territorial waters, dispatching men and women to strip them.Footnote 15

Spanish slaveholders on the Pearl Coast, which encompasses northern Venezuela and the islands of Margarita, Coche, Cubagua, and Trinidad, were the first Europeans to exploit slaves’ African expertise. In 1526, they began purchasing Senegambian and Gold Coast captives to replace indigenous Guaiquerí Indian divers, whose numbers were being decimated.Footnote 16 De Marees observed how Gold Coast Africans were targeted for enslavement on the Pearl Coast, writing that they

can keep themselves underwater for a long time. They can dive amazingly far, […] Because they are so good at swimming and diving, they are specially kept for that purpose in many Countries and employed in this capacity where there is a need for them, such as the Island of St. Margaret in the West Indies.Footnote 17

As discussed below, English salvagers followed Spain's example of purchasing members of African ethnic groups known to possess skilled divers (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The pearl fishery in the Persian Gulf. The Graphic: An Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, 1 October 1881, p. 356.

Salvage divers were cosmopolitan men. Spinning webs of economic, as well as social, cultural, and political connectivity across the Atlantic world, they leveraged aquatic propensities to negotiate dynamic situations and improve their circumstances afloat and ashore, as illustrated by the HMS Mary Rose divers. During the 1540s, before the English crafted concepts of race or slavery, Jacques Francis, John Ik, George Blacke, and five other unnamed African divers were transported to England by Venetian salvager Petri Paulo Corsi to salvage the Rose. When litigation disrupted salvaging, the divers used England's High Court of Admiralty as a platform to secure their legal personhood, challenging still undefined European perceptions of race and slavery that were used during an attempt to marginalize and subjugate them.

While preparing to engage an attacking French fleet on 19 July 1545, the Rose, which was Henry VIII's flagship and one of the world's most modern battleships, sank off Portsmouth, with her deck lying about forty feet below the surface. English salvagers used grappling hooks to “fish” objects from wrecks or looped cables under intact wrecks, and hoisted them to the surface. Both methods failed on the Rose. Italian freedivers were considered the best European salvagers and, in July 1546, the Admiralty appointed Corsi to work the Rose. In July 1547, Corsi was also hired by Italian merchants to salvage the merchantman Sancta Maria and Sanctus Edwardus off nearby Southampton.Footnote 18

Francis “was born” on the “Isle of Guinea”, which is probably Arguin, or Arguim, off Mauritania. Its hydrography (marine geography, including the seafloor, and effects of tides and currents on bodies of water) speaks to the divers’ proficiencies as it is surrounded by “shallows of rocks and sand[bars]” that claimed many ships, providing the aquanauts with fertile training grounds. Arguin was deemed the divide between North and sub-Saharan Africa and “inhabited by black-a-moors”, meaning sub-Saharan Africans. Prior to Portuguese contact, it had been occupied only by migratory fishermen from Senegal during fishing season. The Portuguese built a trade castle there in 1448 to divert commerce away from Timbuktu, transforming the island into an important port and its waters into hinter-seas where divers salvaged Portuguese and African commodities. These divers spoke the same African language, with sources suggesting they were members of Arguin's Wolof merchant/fishing community. They possibly worked wrecks around Gorée Island (Senegal), and were probably Lebu, a Wolof aquacultural ethnic group. Word of their expertise seemingly flowed northward, convincing Corsi to hire them in 1545 to work other wrecks off England.Footnote 19 Corsi could “dyve under the water”, though not as well as Francis, who became head diver, while Ik and Blacke were divers and the other Africans were apparently apprentices. All were treated well, with Corsi “payeng for ther meate [a true luxury] and dryncke at the Dolphin” Inn, which was a Hampton tavern.Footnote 20

Salvaging proceeded until the Italian merchants accused Corsi of stealing items recovered from the Sancta Maria and arrested and sued Corsi in the High Court of Admiralty, prompting Francis to testify. The merchants, who had applauded Francis's expertise, turned on him. Attempting to preclude Francis's testimony, win their suit, and seemingly be awarded the divers as slaves for compensation for their financial losses, they called him a “slave”, “Blacke more”, “morisco born where they are not christened”, and “gynno [Guinea] born”. (These remained imprecise idioms that could aver the inferiority of Muslims and Africans.)Footnote 21

Evidence indicates that the divers were never enslaved, with recent scholarship explaining that sixteenth-century English society regarded Africans as cultural inferiors, yet did not racialize them or accept slavery as a legitimate legal status in England. Corsi never claimed the divers were enslaved, while he seems to have been a member of the middling sorts without the means to purchase them. For his part, Francis testified that he was “of his own free will” in Africa and a servant in England. Ik and Blacke stated they were “servauntes” and “laboryng men”.Footnote 22

The Italians’ strategy failed. The court valued Francis's acumen, allowing him to both testify and defy English notions of inferiority. With his legal personhood secured, Francis used his understanding of English society to go on the offensive, knowing Corsi's freedom would permit them to resume salvaging.Footnote 23 On 8 February 1547, he appropriated symbols of English civility, appearing in court dressed not as a slave but a skilled professional. In testimony recorded in Latin, Francis identified himself as Corsi's “famulus”, meaning “servant” or “attendant”, not “servus” meaning “slave”, explaining they had been in a patron-client relationship for the past “two years”. Francis “dyd handell and see under water” the allegedly stolen items that were “takyn and saved” and would have been restored if Corsi had not been “arreste[d]”. He then accused the Italians of inhibiting the salvaging of the king's ship by arresting Corsi in “Maye”, “the beste tyme” for diving, as seas were calm.Footnote 24

Francis demonstrated that African expertise surpassed all European techniques, using African aquatics to graduate into his elevated position. As a skilled professional, he helped exonerate Corsi. Corsi, nonetheless, spent six months in the Tower of London for abandoning the Rose when Henry Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel, convinced the team to temporarily leave Portsmouth to “take certain of his stuff out of the sea”.Footnote 25

Here, the divers fade from the historical record, though, like watermarks upon paper, they left a lasting impression. The Mary Rose attracted crowds that made the divers famous while introducing the English to African salvaging techniques. From Southsea Castle, perched upon a cliff above Portsmouth, Henry VIII watched her sail into battle and watched her sink. Africans and swimming were novelties in sixteenth-century England and crowds gathered upon Portsmouth's waterfront to watch the divers part the English brine and land recovered goods upon its wharves, speculating upon underwater possibilities with the Earl of Arundel and others hiring them to work England's hinter-seas.Footnote 26

The Mary Rose, Spanish pearl fisheries, and sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spanish successes using enslaved divers to salvage treasure galleons inspired seventeenth-century colonists, especially from Barbados, Jamaica, Bermuda, the Bahamas, Antigua, and the Cayman Islands to begin plundering Spanish wrecks. While Spain remained the owner of treasure ships that went down decades earlier, English colonists viewed these “enemy ships” as the abandoned “Possession of the Devil”, making them legitimate arenas of “frequent and abundant harvest”. Thus, salvagers transformed Spanish shipping lanes into English hinter-seas, reaping Spain's hinterland-produced commodities at very little upfront cost, as illustrated below.Footnote 27

Settled in 1609, Bermuda illustrates how early colonists sought skilled African divers to facilitate personal and colonial success. In 1615 Governor Daniel Tucker proclaimed: “Wee hold yt fitt and have given order that Mr. Willmot” should go to the “Savadge Islands”, or Lesser Antilles, which includes Pearl Coast islands, where it “is hoped he shall there gett […] negroes to dive for pearles” before Bermuda focused on salvaging, as its waters lacked pearl oysters. In 1707, English physician Hans Sloane portrayed this shift as a legitimate process, penning: “Divers, who are us'd to Pearl-fishing, &c. and can stay under Water for some Minutes [were] bought or hir'd at Great Rates and a Ship sent out to bring home Silver”. Early seventeenth-century divers were probably obtained through theft. It is unlikely that Spain sold aquanauts to English salvagers so they could strip Spanish hulks in Spanish-claimed waters. It is equally improbable that Bermudians had the funds to purchase divers. Other sources indicate that Bermudians turned to piracy and the slave trade. In May 1683, Bermudian pirate Jacob Hall participated in a raid on Vera Cruz, Mexico, which possessed a pearl fishery. Seizing “1,230 Negro, Indian, and malato prisoners”, he sold slaves to Bermudian and Jamaican slaveholders.Footnote 28 Later, in the seventeenth century, Gold Coast people were among Bermuda's unwilling colonists. Anchored off Komenda in 1682, an English slaver complained that captives were diverted to a Bermudian slave ship offering African traders better prices. By 1628 many of Bermuda's captives were employed as salvors, perfecting their techniques on old Spanish and Portuguese wrecks.Footnote 29

The recovery of Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de la Concepción was another important salvaging event that had far-reaching repercussions. In 1641, the Concepción, also called the Almiranta or “Ambrosia wreck”, sank in sixty feet of water on Ambrosia Banks (now Silver Bank) off Hispaniola. In 1686, William Phipps colluded with Bermudian captains William Davis and Abraham Adderley, with Phipps providing the financing and the Bermudians the technical expertise, to recover over twenty-five tons of gold and silver worth some £300,000 sterling. They were Atlantic men, with Adderley holding property in Jamaica while Davis had financial interests, and perhaps an estate, in Barbados. Davis arrived at the wreck in a Bermudian “Sloope” that he “fitted” with “ten gunns” in Barbados. Their diver contingents were comprised of captives from Bermuda, Jamaica, and Barbados.Footnote 30

Phipps apparently learned of the wreck's location along Havana's waterfront from Cuban inter-island merchants who saw her submerged hulk. Taking this information to England, he obtained backing from investors who formed a joint-stock company headed by Charles Monck, Duke of Albemarle, who received the exclusive “Patent for all such wrecks” from King James II. Purchasing two ships in London, the Henry and the Bridgewater, Phipps renamed the latter James and Mary after the King and Queen. Sailing for Barbados in September 1686, they re-provisioned and Francis Rogers boarded the Henry as captain, bringing one dugout canoe, and John Pasqua, Francis Anderson, and Jonas Abimeleck, who were enslaved divers from Port Royal, Jamaica.Footnote 31 On 20 January 1687, William Covill, second mate of the James and Mary, and “Francis & Jonas Abimeleck” took the canoe to look for the Concepción. Remarkably, they found her “in 2 hours”, spotting bronze cannons against the seafloor's white sand in forty feet of water.Footnote 32

Numerous other vessels from Bermuda, Jamaica, the Bahamas, Barbados, and Turks Islands descended upon the wreck.Footnote 33 The Concepción was worked by approximately sixty aquanauts, who were probably African-born, as the documented names suggest. Phipps manned the James and Mary with four Mosquito Indians; one was named Amataba, another Sancho. All were pearl divers who had fled Nicaragua.Footnote 34

Divers’ value was measured not by the duration of their labors, but by the value of the goods raised. During brief moments beneath the sea, they produced tremendous wealth. For instance, Adderley hired an unnamed “Negroe” diver, who was probably James Locke, from Mary Robinson of Bermuda. Locke's share (probably between one-tenth and one-twentieth of what Adderley's crew recovered) amounted to 2,358 “pieces of eight”, or Spanish dollars. Pasqua, Anderson, and Abimeleck were similarly productive, with the Henry's log keeping daily tallies of what this team recovered, including several silver bars and plates and over one hundred dollars in silver coin, and other valuables per day. Indeed, 24 February was exceptionally productive, as they gathered 10,105 dollar coins and 518 half-dollar coins.Footnote 35

As Phipps departed “towards England” on 27 April 1687, word of the Concepción rippled across maritime channels of communication, allowing salvagers from English, French, and Dutch colonies to converge upon her before Phipps reached London. Bermudians recovered the most. Adderley and Davis declared three tons of coins and plate worth £27,000. At least thirteen other Bermudian vessels declared almost 17,000 pounds of silver and one ton of gold, worth over £48,000 sterling. Bermudians also mounted twelve salvaged brass cannons in the island's fort to guard their wealth and divers against pirates and a vengeful Spain. Undeclared treasure was also smuggled into Bermuda, and other ports. It was believed that Adderley and Davis underreported their salvage by £15,000-£16,000. Even Governor Robert Robinson engaged in clandestine salvaging. Claiming King James II granted him rights to one-tenth of whatever he salvaged for the colony, Robinson impressed twenty-four enslaved divers and mariners, primarily employing them for his personal benefit. He further profited by collecting the crown's royal tenth on all salvage, underreporting the amount to London, and embezzling the difference.Footnote 36

Phipps demonstrates how salvaging could realign one's stars, while shaping English overseas expansion, with historians concluding that the Concepción “was sufficient to alter the course of England's financial history”. Receiving an investment of £3,200, Phipps reached London with proceeds of between £205,000 and £210,000, making investors’ returns great, even after James II received his royal tenth. Historians believe such returns encouraged the formation of many future joint-stock companies, contributing “substantially to the expansion of the market in stocks in the early 1690s and thereby to the foundation of the Bank of England”. In 1707, Sloane noted that the operation inspired many similar “Projects of the same nature”. For his part, Phipps, who was of humble frontier New England origins, received £8,000, fame, and a knighthood, going on to become Massachusetts’ first royally appointed governor.Footnote 37

Concepción divers changed many Bermudians’ fortunes. Adderley and his salvors each declared shares of 2,358 pieces of eight. Prior to the Concepción, Adderley was a man of modest socio-economic standing. His 1690 estate inventory reflects a sharp economic rise. He purchased eighty-seven acres of land, filling his home with a surprising number of luxury items, including £448 in cash, 1,856 ounces of bullion, a substantial collection of English-made silver spoons, plates, and tankards, two mirrors, topped off by candlesticks plated with recovered Spanish coins. He also purchased fourteen slaves, twenty-five cows, several boats and small ships, and two ship-cannons.Footnote 38

Much of these hinter-seas proceeds were invested in terrestrial production and comfort. Adderley's purchase of land, slaves, and livestock reveals plans for using hinter-seas proceeds to pursue terrestrial production. Phipps's benefits were equally tangible. The Duke of Albemarle gave Phipps's wife “a Present of a Golden Cup, near a Thousand Pound in value” for Phipps honestly delivering the salvage to London. In Boston, where most homes were wood, Phipps “built himself a Fair Brick House”. Additionally, the now Sir William Phipps ascended into the ranks of the nobility, expanding his social, political, and economic connections and opportunities throughout the English Empire.Footnote 39

White salvors incentivized work to extract incomes from divers’ minds and bodies. Most divers were hired out, using this labor system to destabilize typical slaveholder-slave relations by, among other things, exercising varying degrees of control over their lives. Hiring out permitted captives to construct social and political spaces in between slavery and freedom, where they challenged notions of African inferiority by forming work contracts honored by white employers and government officials and making their own shoreside living arrangements. It was lucrative for slave owners, who received a portion of hirelings’ incomes, while employers benefited from slaves’ wisdom and brawn.Footnote 40 Divers’ expertise allowed them to gain far greater benefits than slaves hired into other occupations. Instead of solely relying upon wages to motivate divers, white salvors created hybridized wage-share systems in which divers also received shares.Footnote 41

Affidavits of the Ann from Barbados exemplify this process. Praising the five divers who worked the Concepción, it read “four of ye aforsaid five Divars by name Keazar, Salsbury, Tony & Tom were as good as any that went from Barbados”, and these “Divers [received] four single shares”, while “the Negro Bamko the other Diver, one share”. The Ann also evidences divers’ origins. Most seventeenth-century Barbadian slaves were African-born, and Bamko and Keazar seemingly bore African names.Footnote 42

Divers did not passively wait for white authority to bequeath privileges. They knew their numbers were few, they were not easily replaced, and, without divers, salvagers were largely left to gaze at shipwrecks through clear Caribbean waters. Bermudians knew well-treated divers were more productive, prompting Phipps to hire “Spanish huntrs” to obtain upwards of twenty-nine “wild hoggs” per day. Those suffering from diving disorders and other ailments were granted time off. To reduce injury, diving was performed only in calm seas, often precluding work for several days.Footnote 43 Divers also kept themselves from being sucked into the churning whirlpools of verbal and physical abuse that punctuated the daily experiences of sailors and agricultural slaves. They informed captains that physical punishment prolonged recovery times, and could render them unfit to dive. Indeed, Phipps was notoriously violent towards white officers and sailors, yet refrained from abusing Indian and black divers, and there were only two reported deaths among the approximately sixty Concepción divers.Footnote 44 Hence, divers were well treated – for slaves.

Ashore, aquanauts received roughly the same food, clothing, and shelter as their owners, prompting Governor John Hope of Bermuda to state, in 1722: “They are Strong well Bodied Fellows and well fed”. Many became literate, using this skill to advance their opportunities.Footnote 45 Some free and enslaved salvors became ship captains, commanding white and black mariners. Unfortunately, sources do not describe shipboard relationships under slaves’ captaincies. For instance, Governor Hope simply noted that Turks Island slaveholders dispatched “vessels navigated by negro's” to go “fishing for turtle, diving upon wrecks, and sometimes trading with pyrates”.Footnote 46

Hinter-seas also produced colonists. On 7 December 1781, the Nelly, en route from Calabar (Nigeria) to Jamaica, grounded off Grand Cayman, where Caymanians saved 321 of the 429 captives and all but one crewmember. The vessel's recovery was a pivotal moment in the archipelago's development. Salvaging offered a much-needed economic boost for this backwater Jamaican territory as many of the slaves were sold in Jamaica “to pay salvage”. Some rescued captives, along with bond people saved from subsequent wrecks, became unwilling colonists. A permanent English population dates to 1734, yet the slave population remained small prior to the import of the Nelly's slaves. By 1802, 551 of the 933 inhabitants were of African descent. Salvaging redefined Cayman's shoreside population, providing it with a black majority, while transforming it from a society with slaves into a slave society that cultivated hinter-seas rather than plantations.Footnote 47

Salvaging equally benefited colonies committed to plantation bondage, with Barbados demonstrating planters’ involvement in salvaging. By the 1650s, Barbadian plantation slavery was deep-rooted, allowing sugar to “dominate the Barbadian export sector” in what “was a slave society by at least 1680”. In 1840, Robert Schomburgk reported that “repeated instances of shipwrecks have attracted the attention of successive commanders-of-chief on the West Indian station”, while goods also fell overboard in Barbadian waters and planters hired out divers to work distant wrecks, all of which allowed slaveholders to capitalize on the debris of consumer cultures. As noted above, during the mid-1680s, the Ann from Barbados employed slave divers to work on Concepción. While sources document the regularity of shipwrecks in Barbadian waters and lighthouses were built during the late nineteenth century to reduce their frequency, records detailing salvaging in Barbadian waters have not been located. For example, between 1820 and 1834 sixteen ships wrecked on Cobbler Reef in Long Bay off Sam Lord's cotton plantation. Male and female slaves saved mariners and plundered these wrecks, which apparently provided capital necessary to construct Lord's “Long Bay Castle”. Completed in 1831, it was “one of the finest mansions in the West Indies”, making it “an oasis in the desert” of far more modest neighboring estates. Its elaborately carved ceiling took English and Italian craftsmen three years to complete and Lord lavishly furnished it with an array of fine English furniture, silverware, china, glass, books, and decor. Perhaps to conceal his duplicity, Lord provided no written record of these shipwrecks.Footnote 48

Divers in maritime and plantation colonies gained similarly, benefiting from the flexibility of maritime bondage. Enslavers promoted arduousness by avoiding coercive discipline, nurturing a sense of mutual obligation arising from collective responsibilities, and extending material rewards. They cultivated reciprocal relationships binding slaves to multi-racial crews and the islands where their families lived, while implicit threats of selling family members transformed them into hostages, compelling divers to return home. As the eighteenth century progressed, multi-racial kinship ties increasingly bolstered shipmate affiliations. Many whites went to sea with biracial men whom they owned. Some recognized divers as relatives, allowing aquanauts to use white familial ties to advance their positions. For instance, by 1824 it was said that “most” Bahamians “have a dash of dark blood in their veins & many are mulattoes”.Footnote 49

Divers cloistered their wisdom, creating semi-fraternal orders that precluded slaveholders from appropriating and propagating their aquatic fluencies, as occurred when South Carolina planters integrated African rice-producing methods “within applicable European farming strategies without the need to offer compensation”.Footnote 50 Beneath the sea, African wisdom outperformed European technology and techniques, providing aquanauts with sway. Concurrently, gender prejudices impeded white attempts to control divers. Skilled labor was a “gendered phenomenon” favoring bondmen as “enslaved women found themselves confined to the monotony and drudgery of the field more regularly than their male counterparts”. Many African-descended women were expert divers. Yet, beliefs that maritime labor was a male occupation precluded women from salvaging. In the absence of this gendered bias, slaveholders could have swelled divers’ numbers to increase their control over salvaging.Footnote 51

FORGING BONDS BETWEEN SEAPORTS AND HINTER-SEAS

Divers’ ability to retain privileges in homeports hinged on more than linking seaports to hinter-seas. They had to inform white port residents of their ability to transform what would have otherwise been production-less shipping lanes into arenas of substantial economic production. Many New World ports were small, while maritime colonies functioned as ports that were home to small interconnected populations. This spatial arrangement and related social geography allowed most residents to palpably experience how salvagers benefited them. For instance, the historian Michael Jarvis explained that the spending practices of salvagers who worked the Concepción infused Bermuda with considerable amounts of capital, “spreading much of their cash throughout the island”, in ways benefiting all Bermudians. This seemingly convinced them, in some important ways, to treat divers like free, skilled laborers.Footnote 52

Smuggling salvage into port strengthened the bonds between seaports and hinter-seas. Divers were central in producing salvage and smuggling it across imperial borders and into homeports, as demonstrated when English salvors secreted Concepción salvage out of the Spanish Empire and into English ports. Even though most of the salvage was declared in London and colonial ports, much went undeclared. Scholars have convincingly argued that intra- and inter-imperial seaborne smuggling benefited most seaport residents. Most seaport residents understood how smuggled salvage improved their material circumstances and that divers offloaded, hid, and helped launder undeclared wealth. The Concepción's unreported salvage was a poorly kept secret, with many Bermudians, including officials, openly discussing and displaying their smuggled wealth. Likewise, Caymanians exemplify how cargoes and ships were used to build and ornament salvagers/wreckers’ homes. Ships’ hinges, latches, windows, and timber were repurposed, while French tiles pulled from one wreck adorned the floors of several homes. Duplicity in smuggling and wrecking probably provided divers with privilege-extracting leverage bolstered by white people's understanding that aggrieved divers could disclose their unlawful activities.Footnote 53

Divers continually endeared themselves to white elites by employing hydrographic and maritime aptitudes in corollary professions. Between salvage operations they worked as ship pilots, fishermen, sea turtlers, sponge and conch divers, and coastal and inter-island sailors. These occupations allowed divers to cultivate nuanced understanding of hydrography and weather patterns that precipitated shipwrecks while situating them to find recent wrecks.Footnote 54

Using their incomes and white connections, some obtained freedom, becoming independent salvagers, while improving family members’ circumstances, as James Locke demonstrates. Abraham Adderley helped Locke purchase his liberty from Mary Robinson and then purchase his sister, Betty, and her son, “Jethrow”. Sources suggest that most freed divers maintained bonds with white patrons, who advanced their interests and shielded them from abuse. For instance, Adderley and Locke seemingly colluded to gain Locke's freedom so they could salvage without Robinson's interference.Footnote 55

As divers circulated the Atlantic world, seaports became concentric links in the sprawling constellation of communities created as aquanauts and other maritime slaves cast far-reaching lines of connectivity.Footnote 56 Seaports were important places and structures for harnessing skilled labor, while converging human currents accumulated, interlaced, and disseminated global knowledge that had been developed on African, European, and New World hinter-seas. There “was no center to the Atlantic, although there were nodal points with their own centripetal political, economic, and cultural forces, notably in urban areas, where Atlantic peoples met, shared information, and circulated ideas, things, and people between themselves in ongoing, reciprocal, contestable networks”. Seaport residents, including divers, were “quintessential Atlantic people”.Footnote 57

At docks, aquanauts exchanged salvaging techniques, speculated on how recent storms exposed sand-covered wreckage, learned how shipping and weather patterns conspired to sink and accumulate colonial wealth in somewhat predictable places, and considered the possible locations of missing vessels. Seaports contained vibrant multiracial institutions catering to maritime workers’ desires while serving as marketplaces of information that advanced black and white salvagers’ economic opportunities. The murmurings of the Atlantic world floated into taverns and brothels, where prostitutes, customers, and barkeepers gleaned information about shipwrecks, passing it on to receptive divers and white salvagers.Footnote 58 It was along Boston's waterfront that William Phipps acquired his initial lessons on salvaging. On 16 October 1683, three years before salvaging the Concepción, shipmaster Peres Savage boasted how he “consorted” with six other captains to assemble thirty “good divers” to partially salvage a Spanish wreck in the Bahamas. This foray informed Phipps of the importance of enslaved divers. Similarly, Petri Corsi, Jacques Francis, and the other African divers frequented English taverns, where they were hired by merchants whose ships had sunk in England's hinter-seas.Footnote 59 As rumors of shipwrecks drifted into seaports upon the lips of mariners and pages of newspapers printed in far-off ports, white salvagers amassed teams of enslaved divers, slipping off to create new hinter-seas.

Port Royal, Jamaica was an important center for salvaging, providing a unique opportunity for divers to create a new hinter-sea. It was also the largest seventeenth-century Caribbean city and “one of the world's great harbors”. White pirates and salvagers assembled teams of “Diving Negroes” to work wrecks around its shipping lanes, amassing their treasure in waterfront homes. On 7 June 1692, an earthquake caused much of this seaport to slide beneath the ocean, transforming it into a hinter-sea for Kingston and what remained of Port Royal. The submerged town became the long-term training ground for over 200 enslaved divers who, for more than thirty years, entered its partially collapsed structures. It can be inferred that its waters, wharves, and taverns were important places for concentrating, perfecting, and disseminating techniques. In 1687, John Pasqua, Francis Anderson, Jonas Abimeleck, and other divers carried their expertise from Port Royal to Barbados, then to the Conceptión. After the earthquake, they probably swam along streets they had once walked. While there are no known descriptions of this salvage operation, twentieth-century underwater archaeologists reported that enslaved divers were “quite thorough and good at their work; missing very little of value”, stripping structures so “there was absolutely nothing to be found”.Footnote 60

Port Royal divers quickly mobilized to other hinter-seas. In September 1730, the fifty-four gun “Spanish Man of War” Genoesa wrecked upon Pedro Bank (about forty miles south-west of Jamaica) carrying a “great Treasure”. Sea turtlers rescued the Spaniards, depositing them ashore, and began stripping the Genoesa. To preserve the Asiento, or contract, allowing Britain to import slaves into the Spanish Americas, Governor Robert Hunter of Jamaica sought to secure the vessel, requesting English “Ships of War to guard the Wreck” and asked “the Gentlemen” of Port Royal to lend their divers to recover “all such Treasures” they could. Arriving at the Genoesa, Captain Ware, who commanded a “Sloop”, encountered unsanctioned salvagers, turned wreckers, pillaging her. Instead of safeguarding the vessel, Ware colluded with them and “fish'd up a great deal of Treasure. The third day while they were at work upon her”, the HMS Experiment arrived. Ware claimed to be securing the treasure and “readily promised” to load it aboard the Experiment the following morning, but slipped off in the night. The Experiment gave chase before leaks forced her to return to Port Royal, allowing wreckers to descend upon the Genoesa before she was secured by the HMS Tryall, which recovered 31,695 gold and silver coins, 105 silver ingots, and eight bars of gold. Spaniards also “fish'd up and brought from the said wreck a good deal of treasure etc.”. Regardless, Governor Hunter concluded that wreckers made off with most of the treasure, accusing Neal Walker, commander of a sloop belonging to the South Sea Company, of looting gold and 16,000 pieces of eight, which was “shar'd and divided the same among themselves in a private and clandestine manner”, on Little Cayman Island. Hunter also exclaimed that “there had been other vessels in a clandestine manner fishing upon her, and that part of the treasure had been landed in remote parts and there concealed and secreted”.Footnote 61

Among other things, the Genoesa illustrates divers’ ability to quickly strip wrecks, while underscoring the acceptance of wrecking and smuggling. Wreckers secreted salvage into Jamaica and Cayman Islands, where merchants accepted Spanish coins as payment. Furthermore, English officials openly engaged in wrecking, as both Ware and Walker were employees of public-private trading companies and both seemingly escaped punishment.

Divers’ ability to link seaports to lucrative hinter-seas afforded privileges that made them targets of those seeking to appropriate their bodies and wisdom, as illustrated by Ned Grant, a Charleston, South Carolina diver. Grant was stolen by pirates and, after he had been recovered, Charleston officials conspired to appropriate him. On 27 September 1718, Grant and nine other slaves were captured in North Carolina's Cape Fear River, with Barbadian planter-turned-pirate Stede Bonnet. The ensuing piracy cases were tried by Judge Nicholas Trott in the South Carolina Vice Admiralty Court.Footnote 62 As typical in piracy cases, on 17 November Grant became part of the litigation over Bonnet's “Sloop Revenge”, her “Negroes Goods & Merchandise”. William Rhett, a planter and slave trader, led the expedition against Bonnet, claiming Grant as “Salvage”, meaning Rhett was entitled to a share of his value. Grant's owner, the widow Catherine Tuckerman, sought his return, explaining she “hired” him “to one Captain Barrett” who “took him to the Wrecks for a Diver”, referring to the 1715 Spanish Plata (Silver) Fleet that sank in a hurricane off Cape Canaveral, Florida. Known as the “Bahama Wrecks”, pirates from Port Royal, the Bahamas, Bermuda, and elsewhere drove Spanish salvagers off to plunder the hulks. There, Grant was “taken [stolen] by one Capt. Burgess a pirate and by him Carried to the Bahama Islands”. Grant escaped to New England, where he boarded a vessel “bound for Great Britain which was afterwards taken by Stede Bonnett the Pirate”. At this juncture, Grant was apparently recognized as a diver or disclosed his aquatic acumen to escape harsh treatment, for Bonnet took him back to the “Bahama Wrecks”, and then North Carolina.Footnote 63

Judge Trott detested pirates as “Enemies of Mankind”, believing salvagers “gave birth and increase to all the Pirates in those Parts” as both preyed upon others’ misfortune. There was no evidence that Grant engaged in piracy and Trott could have returned him to Tuckerman. Instead, Trott ruled that Grant was “a notorious Renegade”, sentencing him to be “publicly sold”, with half the proceeds going to Tuckerman, the other to Rhett, who was Trott's brother-in-law.Footnote 64

Grant's ability to link the small but significant port of CharlestonFootnote 65 to fertile hinter-seas made him an important fixture in this seaport. Trott seemingly condemned Grant so Rhett would profit from his sale. To Trott's chagrin, Tuckerman paid “the Salvage” to repurchase her slave for far less than he would have been sold for at auction. Undoubtedly motivated to regain and exploit her property, Tuckerman's actions, nonetheless, rescued Grant from an uncertain future, reuniting him with family and friends.Footnote 66 Grant demonstrates the limits of divers’ humanity, made palpable when, like all slaves, whites sought to possess and control their wisdom and expertise.

While hinterlands lay close to seaports, hinter-seas could be far off, allowing colonists to profoundly expand their arenas of economic production. Seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century divers’ success in stripping known Spanish treasure ships prompted salvors to engage in wrecking and cross the Atlantic. The Hartwell exemplifies these shifts in the pursuit of profits. On 23 May 1787, the Hartwell, the largest and one of the “finest ships” in the British East India Company's (EIC) fleet, sank in forty feet of water off Boa Vista Island, in the Cape Verde Islands off West Africa. Carrying money and trade goods with which to purchase Indian commodities, it contained sixty chests of silver coins worth £153,642, three chests belonging to the ship's owner, “several packages of private trade”, and one hundred lead ingots. London newspapers chummed the channels of maritime communication with exaggerated tales of her fortunes while describing how enslaved and free Cape Verdians worked her, luring wreckers across the Atlantic.Footnote 67

William Braithwaite of London and his sons, John and William, Jr, secured the EIC contract giving them exclusive rights to salvage the Hartwell. They had developed a steam engine to pump air into diving bells, believing this modern technique was the most efficient way to salvage wrecks. Working the wreck during summer months from 1787 to 1790, the EIC hired British warships to guard the site before deeming it unnecessary in the early summer of 1789. By mid-summer “five Piratical vessels” were “lurking about”, like hyenas circling lions’ kill, “plundering the Hartwell” whenever the Braithwaites chased one wrecker off. On 29 August 1789, five heavily armed wreckers drove the Braithwaites off and teams of divers stripped her faster than the Braithwaites could.Footnote 68

The wreckers worked unmolested until the HMS Pomona, captained by Henry Savage, who was part of Britain's West Africa Squadron, arrived on 29 October, capturing the Brothers. From John English, one of the Brothers’s seven enslaved divers, Savage gleaned the wreckers’ Atlantic origins. The sloop was from St Eustatius in the Dutch West Indies and sailed under the Danish flag. Captain Thomas Hammond was from New York, the mate was Scottish, and they “procured seven Negroes Men Divers”, from St Thomas in the Danish West Indies. Hammond partnered with a slave ship's “Tender belonging to St. Thomas” and commanded by “a native of Ireland”. These divers recovered some 20,000 silver coins. Aquanauts belonging to the other wreckers were equally productive. Mary was captained by “a native of Rhode Island”, flew a Dutch flag, and recovered “10,000 Dollars” before returning to its homeport of St Eustatius. The Swift, also of St Eustatius, flew “Swedish Colours” and “got about 8,000 Dollars”, but “lost their best diver”. Another sloop was stolen “from some English Port” by “an Englishman” and commanded by “Lumbard” of Cape Cod, Massachusetts.Footnote 69

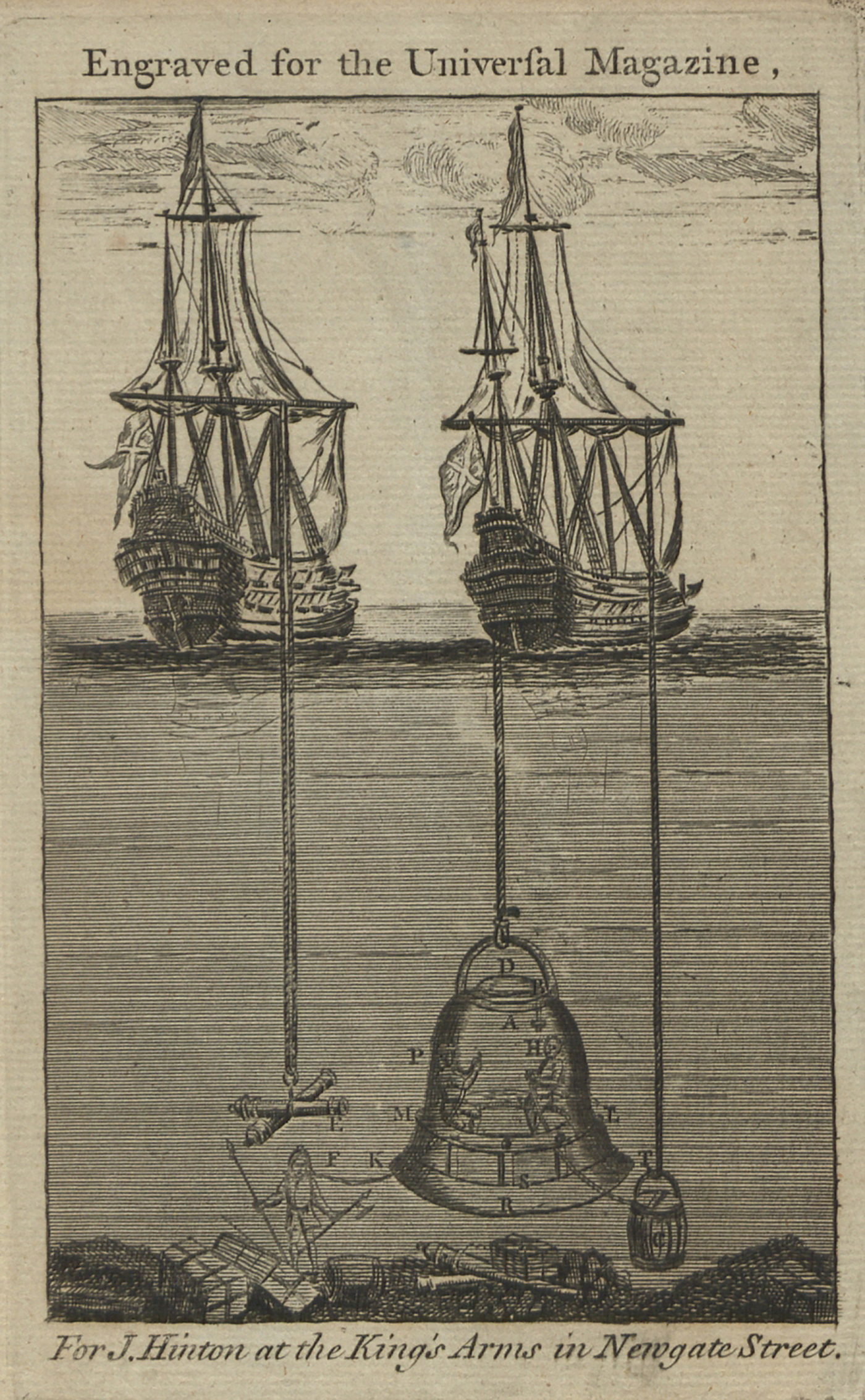

Westerners routinely believe in the unfaltering “triumph of modernity over tradition” and the EIC was both an instrument of British imperialism and juggernaut of corporate sovereignty.Footnote 70 The London Times praised the Braithwaites’ “extraordinary genius” as a monumental improvement over “Dr. [Edmund] Hailey's diving-bell” (Figure 3), allowing them to remain “underwater for six weeks, or any length of time”. Regardless, freedivers’ centuries-old wisdom capsized this assumption, as African-descended aquanauts stripped this EIC leviathan faster than the Braithwaites could with the steam-driven technology of a modern industrializing Britain. Diving bells were difficult to negotiate around wrecks, too big to enter holds, while the masts, yardarms, and rigging of recent wrecks threatened to capsize bells and snare their lines and air hose. Methods for replenishing air supplies were unreliable, frequently causing divers to suffocate. The Braithwaites’ technique was a significant improvement. Regardless, their engine could only pump air twelve feet deep, requiring the bell to be frequently raised from the Hartwell, while its limited mobility enabled nimble, incentivized freedivers to outperform it.Footnote 71

Figure 3. Halley's diving bell, engraved for the Universal Magazine, Printed by J. Hinton, London, eighteenth century.

©Museum of the History of Science, University of Oxford.

The Brothers punctuates aquanauts’ potentially fragile circumstances. Captain Hammond apparently told the owners of the captured divers that they would legally salvage a shipwreck. Upon returning home, their shares were to benefit their lives and those of their enslaved family members. Charged with piracy, they never returned home. The divers became salvage, and six were sold to compensate the EIC for its losses. John English was “kept on Board the Pomona as an Guidance [perhaps meaning pilot]” and cook, which raises provocative questions. His surname and ability to speak English imply previous British associations, while Savage's decision to retain him as a pilot in the West Africa Squadron intimates understandings of African hydrography.Footnote 72

CONCLUSION

We routinely consider the past with our backs to the ocean, assuming seas were watery roads that connected ports to each other while social, cultural, and economic production occurred ashore. We leave water out of maritime histories, treating them as dry experiences that unfolded upon ship's decks and docks, while ignoring non-Westerners’ maritime traditions. Likewise, scholars regularly situate seaports between hinterlands and overseas markets. As important areas of rural production, hinterlands rise to the analytical foreground while seaports slip to intellection horizons, becoming mere entrepôts – sometimes metaphors – for connecting countrysides to distant consumers. Divers directed ports’ eye to hinter-seas of production. This essay encourages scholars to view the world from different perspectives. Face seaward; slip into the intellectual drink to consider immersionary cultures and how divers informed seaports’ structures and functions.

Seas were places of hope and opportunity for those capable of negotiating them. Standing upon wharves while gazing towards hinter-seas, black and white salvagers knew unique prospects lay beyond horizons and beneath the water's surface. Using African-derived expertise to harvest the human debris of commercial capitalism, divers transformed shipping lanes into hinter-seas.

Even as white people enslaved African bodies and colonized dry spaces, the turbulence of maritime slavery destabilized their authority afloat, providing shipboard opportunities for captives.Footnote 73 Divers found still greater benefits beneath the waves. Even as planters imposed high rates of suffering and death on manacled field-hands, salvagers treated divers well.

Enslaved divers were not simply carried by the tides of others. From the deep, aquanauts generated undercurrents of wealth and power that, in some important ways, allowed them to chart their own course even while remaining enslaved. Employing their expertise, they deflected the prevailing winds of racial/social subjugation. As planters, capitalists, and manufacturers increasingly imposed clock discipline on laborers, divers harnessed the ocean's rhythms to resist such regulation.Footnote 74 Salvaging was largely limited to spring and summer months and, then, only during the morning calm, requiring aquanauts to dive less than two hours per day, while their enslaved brothers and sister toiled the length of their days in agricultural fields. Divers retained premodern share systems that compensated them far more than wages. They also pushed the boundaries of what is typically imagined by the “Black Atlantic” and “greater Caribbean”, bringing European and African hinter-seas, seaports, and port communities into their orbits of understanding.Footnote 75

It is time to take the deep intellectual dive. By incorporating the ocean into Atlantic history and immersionary traditions into maritime deliberations, we can expand our intellectual horizons by thousands of miles, both across and below the water's surface. But, oceans are not one vast environmental expanse. Examining seaports’ relationships with hinter-seas, we can begin to understand how discrete maritime regions informed human circumstances in different ways. Hopefully, “History Below the Waterline” will be the breath before the plunge as we plumb the depths of African-descended people's aquatic cultures.