No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2017

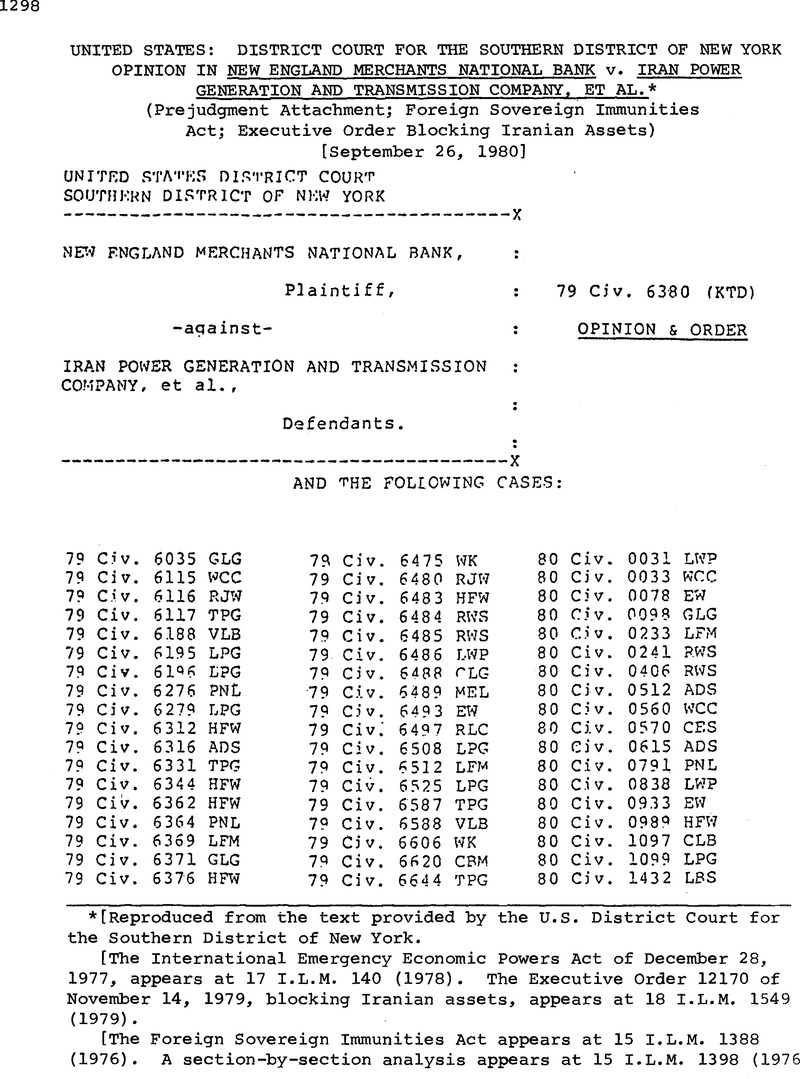

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.

[The International Emergency Economic Powers Act of December 28,1977, appears at 17 I.L.M. 140 (1978). The Executive Order 12170 of November 14, 1979, blocking Iranian assets, appears at 18 I.L.M. 1549 (1979).

[The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act appears at 15 I.L.M. 1388(1976). A section-by-section analysis appears at 15 I.L.M. 1398 (1976

1 There are 96 individual complaints, each relvina upon a separate cluster of operative facts which give rise to the several claims. The majority of claims seem to be grounded in contractual repudiation. However, many of the complaints seek relief for conversion as a result of the nationalization of various business ventures which,prior to the present political upheaval in Iran, were private commercial enterprises.

Despite the myriad of legal theories advanced, the essence of the claims is that the government of Tran, its agencies and instrumentalities, have expressed an unequivocal intention of avoiding their just debts.

2 Rule 64 provides:

At the commencement of and during the course of an action, all remedies orovidinq for seizure of person or property for the purpose of securinq satisfaction of the judgment ultimately to be entered in the action are available under the circumstances and in the manner provided by the law of the state in which the.district court is held, existing at the time the remedy is sought,

The remedies thus available include arrest, attachment, qarnishment, replevin, sequestration, and other corresponding or equivalent remedies, however designated and regardless of whether by state procedure the remedy isancillary to an action or must be obtained by an independent action.

3 The majority of attachments were granted at a time whenany communication between Iran and the United States wasvirtually impossible and prior to the retention ofcounsel by the various Iranian defendants. Consequently,many of the orders of attachment were issued ex parte.However, counsel was soon retained bv defendants andsubsequent orders of attachment were issued only uponnotice to defendants.

Procedural1y, New York's attachment statue distinguishesbetween or parte orders of attachment and those issued on. notice. With respect to the ox parte orders, the partv seekinq the order must move to confirm the attachment within five (5) days. §6211(b). However, when the order is issued upon notice, the initial burden is upon defendant to move to vacate the attachment. §6223 (a).These procedural distinctions account for the instantmotions and cross-motions.

4 As is evident from the discussion thus far, the instantactions have been consolidated before ne for the limitedpurpose of determining whether the Immunities Act immunizes defendants' assets from a pre-judgment security attachment. The issue of jurisdictional immunity, if it is to be asserted, is not an issue which is before me and accordingly I make no finding with respect thereto. I merely note that none of the parties have urged that the instant attachments act as a jurisdictional predicate. Rather, plaintiffs relv upon 28 U.S.C. § §1330(a) and 1331 as the basis of subject matter jurisdiction over the instant disputes and 28 U.S.C. § 1330(b) as the basis of personal jurisdiction over thedefendants.

5 For example, some, but not all, of the defendants have asserte the “act of state” doctrine as an absolute defense to their actions in connection with the various commercial activities in issue. In addition, many of the bank defendants have asserted that the funds which are the subject of the instant suits constitute funds held for the bank's own account and are thus immune from attachment and execution. It is enough to note thatthese defenses, however meritorious, must be dealt with on a case by case basis by the individual judge to whom they are assigned.

Although I need not decide the merits of the several uncommon defenses asserted by the defendants, I feel I must comment on at least one of these defenses. At the joint confirmation hearing held in this matter, the Bank Markazi engaged in substantial argument in an effort to establish itself as the Central Bank of Iran.

From what was said at argument, it is clear that the question has been put in issue but it is far from settled. It would appear to that the Bank bar the burden of proof in this rooard and that it must produce much more to sustain that burden.

6 Despite the numerous arguments advanced by the parties, as well as the voluminous papers submitted with respect to the instant motions, no one has urged that the Treaty of Amity is no longer in effect. and, although some are quick to point to Iran's apparent violation thereof, there has been no indication by the Executive Branch that it considers the Treaty of Amity at an end.

7 I also note for the record that at least one of the actions before me involves an arbitration provision. See Reading & Rates v. National Iranian Oil Co. , No. 79-6035. However, despite the fact that a virtually identical arbitration provision has been found to constitute a waiver of sovereign immunity, Ipitrade International v. Federal Republic of Nageria 465 F.SUPP. 824 (D.D.C. 1978) , plaintiffs' counsel, when Questioned on the point, declined to pursue arbitration. See also Reading & Pates, supra, 478 F. Supp. at 726.

I raise this point insofar as it may prove fruitful in the case by case treatment which must necessarily follow.

8 The other argument raised by the government in this connection is totally devoid of any merit.