To the Editor—Previous reports have demonstrated low hand-hygiene (HH) compliance in emergency departments (EDs).Reference Muller, Carter, Siddiqui and Larson 1 , Reference Wiles, Roberts and Schmidt 2 Barriers to compliance in this setting include crowding, higher patient acuity, nonstandardized workflow, higher staff turnover, lower penetration of HH promotion activities, and high representation of doctors in ED audits, a group with known suboptimal HH compliance.Reference Muller, Carter, Siddiqui and Larson 1 , Reference Carter, Wyer and Giglio 3 , Reference Scheithauer, Kamerseder and Petersen 4 We sought to use a nationwide dataset to describe HH performance in Australian EDs and to test the hypothesis that lower HH compliance in EDs is explained by a higher proportion of observed HH activity by doctors in this setting.

We used data collected for the Australian National Hand Hygiene Initiative (NHHI), which is described elsewhere.Reference Grayson, Russo, Ryan, Havers and Heard 5 Briefly, the NHHI was launched in 2008 as a standardized national approach to HH culture change adapted from the WHO Multimodal Hand Hygiene Improvement Strategy. 6 At the institutional level, the core components of the NHHI are alcohol-based hand rub at the point of care, healthcare-worker education about HH and infection control, and HH auditing with performance feedback using the WHO “5 Moments” methodology. The NHHI uses a train-the-trainer model for HH auditors. National and jurisdictional representatives train “gold standard auditors” (GSAs) during a 2-day workshop; GSAs can then train “general auditors” in their own organization with a 1-day workshop. Each year, auditors must collect at least 100 moments and must complete an “auditor validation” online learning module and quiz to maintain auditing competency. Since 2011, the interim national benchmark for HH compliance has been 70%, and aggregate institution-level compliance has been reported publically online. 7 In 2013, implementation of the NHHI became a requirement for hospital accreditation. 8 The program focuses on inpatient wards, with no explicit national requirement to include emergency departments.

We compared HH compliance in EDs, high-risk wards, and other acute-care inpatient wards. According to the NHHI definition, high-risk wards include critical care, renal, hematology/oncology, and transplant wards. We included hospitals that submitted HH compliance audit data during National Audit Period 1 2016 (November 2015–March 2016) and belonged to an Australian Institute of Health and Welfare hospital peer group indicating the presence of a 24-hour ED (ie, principal referral hospitals, public group A hospitals, public group B hospitals, and private group A hospitals). 9 Hand-hygiene compliance was computed as the proportion of moments during which an HH action (hand rubbing or washing) is performed, expressed as a percentage. We performed a χ2 test to assess the independence of ward type and others categorical variables, including HH action and healthcare-worker profession, at the HH moment level. We used multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression to evaluate the relationship between ward type and HH compliance after adjusting for profession and HH indication. We accounted for hospital-level clustering by including hospitals as a random effect.

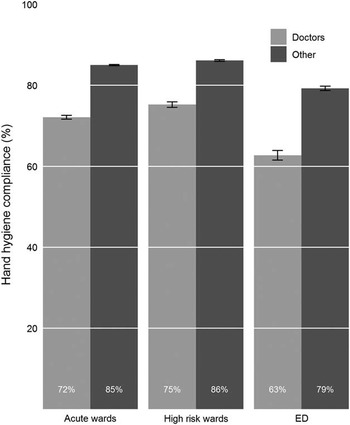

Overall, 152 hospitals were included in this analysis: 132 public (87%) and 20 private (13%). These hospitals submitted 369,162 HH moments. Overall, 108 of these hospitals (71%) submitted HH moments from their EDs, for a total of 20,872 HH moments. Hand-hygiene compliance was lower in EDs than in acute-care and high-risk wards: 20,872 of 27,686 (75%) in EDs, 185,057 of 222,819 (83%) in acute-care wards, and 100,402 of 118,657 (85%) in high-risk wards (P<.001). Doctors represented a higher proportion of observed moments in EDs than acute-care and high-risk wards: 6,467 of 27,686 (23%) in EDs, 33,742 of 222,819 (15%) in acute-care wards, and 16,544 of 118,657 (14%) in high-risk wards (P<.001). In addition, doctors had significantly lower HH compliance in EDs than acute-care and high-risk wards: 4,057 of 6,467 (63%) in EDs, 24,336 of 33,742 (72%) in acute-care wards, and 12,447 of 16,544 (75%) in high-risk wards (P<.001, Figure 1). After adjusting for profession and HH indication, hand-hygiene compliance remained significantly lower in EDs than in acute-care inpatient wards (adjusted odds ratio, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.57–0.60), which suggests that other factors may be involved.

FIGURE 1 Aggregate hand-hygiene compliance, stratified by ward type and profession.

NOTE. High-risk wards include critical care, renal, hematology/oncology, and transplant wards. Abbreviations: ED, emergency department.

Doctors account for a significantly greater proportion of observed HH opportunities, and have lower HH compliance, in EDs than in inpatient wards. Lower HH compliance in EDs is therefore not explained solely by healthcare-worker profession or by HH indication. Overall, we believe that this finding relates to a combination of 2 interrelated factors. First, coordinated strategies to improve HH have targeted inpatient wards rather than EDs. Second, EDs represent a unique setting with distinct environment, staff, and patient factors compared with inpatient wards. Interventions as simple as ensuring availability of ABHR at the point of care are more complex in the ED setting. In summary, there is a need for greater focus on identifying modifiable barriers to appropriate HH in Australian EDs and on implementing targeted initiatives to improve HH behavior.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge all groups and individuals contributing to the National Hand Hygiene Initiative, including Hand Hygiene Australia team members, the ACSQHC Healthcare Associated Infection Program, the NHHI Advisory Committee, NHHI Jurisdictional Coordinators, infection control professionals, and HH auditors.

Financial support. No financial support was provided relevant to this article. A.J.S. and M.L.G. receive salaries from Hand Hygiene Australia, funded by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.