Introduction

The community care unit (CCU) model of psychiatric rehabilitation was established in Australia based on the successes in transitioning former long-stay psychiatric inpatients back into the community demonstrated in the United Kingdom (Trauer et al., Reference Trauer, Farhall, Newton and Cheung2001). Contemporary CCUs provide time-limited, clinically-oriented residential psychiatric support focused on improving multiple aspects of personal functioning – primarily living skills development and community integration – in the context of overall mental health (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Hopkins, Siskind, Harris, McKeon, Dark and Whiteford2019). These clustered, independent living units provide 24-h rehabilitation support to people whose functioning is affected by serious mental illness (Meehan et al., Reference Meehan, Stedman, Parker, Curtis and Jones2017). Most CCU consumers will have experienced recurrent and lengthy hospitalisations (Meehan et al., Reference Meehan, Stedman, Parker, Curtis and Jones2017). The costs associated with the provision of intensive rehabilitation care in a residential setting support the need for accountability regarding service effectiveness (Iyer et al., Reference Iyer, Rothmann, Vogler and Spaulding2005; Murugesan et al., Reference Murugesan, Jeffrey, Amey, Deane, Kelly and Stain2007).

There is limited evidence available considering the outcomes of community-based residential rehabilitation (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Hopkins, Siskind, Harris, McKeon, Dark and Whiteford2019). Psychiatric rehabilitation aims to improve psychosocial functioning and facilitate personal recovery (Farkas and Anthony, Reference Farkas and Anthony2010); hence, mental health symptoms and social outcomes may reflect appropriate outcome foci (Tulloch et al., Reference Tulloch, Fearon and David2008). However, societal outcomes such as hospital use (Bunyan et al., Reference Bunyan, Ganeshalingam, Morgan, Thompson-Boy, Wigton, Holloway and Tracy2016) and accommodation stability (Killaspy and Zis, Reference Killaspy and Zis2013) are slower to change and better reflect the broader costs associated with schizophrenia (Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Bruckner and Brown2013).

Evaluations of residential psychiatric rehabilitation services have considered a range of outcomes but tend to individually focus on only one or two relevant domains (online Supplementary Table 1). These studies have found improvements in mental health and social functioning (Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018), but have not addressed measures of independence which have been found to improve following engagement with other rehabilitation services (Killaspy and Zis, Reference Killaspy and Zis2013; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Bruckner and Brown2013). Furthermore, some studies have relied on single time-point outcome measures such as time to re-hospitalisation or inpatient days post-discharge (Grinshpoon et al., Reference Grinshpoon, Abramowitz, Lerner and Zilber2007).

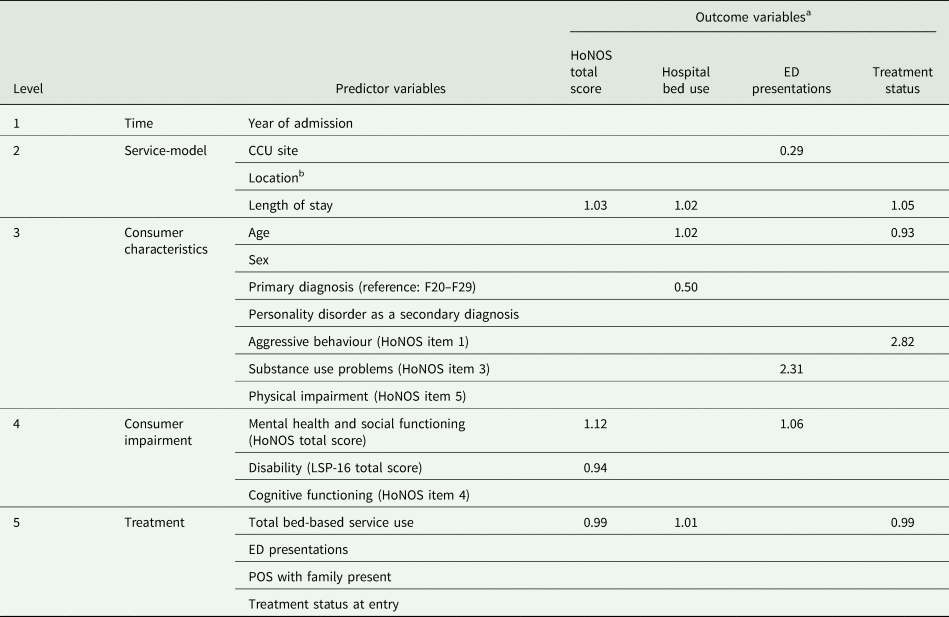

There has been limited research examining predictors of rehabilitation outcomes (Vita and Barlati, Reference Vita and Barlati2019). A range of predictors have been identified (see Table 1), but studies generally fail to consider a broad range of relevant predictors; notably cognitive functioning, a strong predictor of positive outcomes in vocational rehabilitation (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Bond, Meyer, Kim, Lysaker, Gibson and Tunis2004) and of functional outcomes generally for people diagnosed with schizophrenia (Brune et al., Reference Brune, Schaub, Juckel and Langdon2011). Moreover, data is often collected from multiple service locations without examining the effect of site and other geographic factors. It is plausible that outcomes may be impacted by site-specific practices or the availability of other services in the region.

Table 1. Summary of studies evaluating the outcomes of psychiatric rehabilitation in people with schizophrenia

BPRS-E, Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale-Expanded version; HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; K10, Kessler 10; LSP, Life Skills Profile-16; NSW, New South Wales; OR, adjusted odds ratio; RCS, reliable and clinically significant; SLOF, specific levels of functioning; UK, United Kingdom; USA, United States of America.

The importance of assessing the reliable and clinically significant (RCS) change rather than statistical significance in outcome evaluation has been emphasised (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018). Instead of assessing change at the group level (e.g. considering average scores), this approach considers the magnitude of changes for individual participants (e.g. their difference between pre-admission and post-discharge scores) and allows for comparison with normative data. Such assessments may provide a more appropriate measure of rehabilitation outcomes (Trauer, Reference Trauer2010). Several studies have reported RCS improvement following psychiatric rehabilitation (Barbato et al., Reference Barbato, Agnetti, Frova and Guerrini2007; Murugesan et al., Reference Murugesan, Jeffrey, Amey, Deane, Kelly and Stain2007; Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Pillai, Jain, Cohen and Patel2009; Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012; Killaspy and Zis, Reference Killaspy and Zis2013; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018). However, the availability of appropriate functional population data remains a challenge. For example, Murugesan et al. (Reference Murugesan, Jeffrey, Amey, Deane, Kelly and Stain2007) reported RCS psychosocial functioning improvement following in-patient psychiatric rehabilitation in Australia using an Italian community sample for the functional population data.

The present study measured the extent of improvements in outcomes among consumers accessing CCUs in Queensland between 2005 and 2014, and explored predictors of these outcomes. The approach taken expands on previous studies by including a broad range of relevant outcomes and potential predictors. Based on previous research (e.g. Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012; Killaspy and Zis, Reference Killaspy and Zis2013; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018), we hypothesised that CCU care would be followed by RCS improvement in mental health and social functioning between the year pre-admission and post-discharge. Improvements were also expected in service use, accommodation instability, disability and reduced involuntary treatment. Additionally, it was expected that outcomes would be predicted by a range of service-, consumer- and treatment-level factors.

Method

Design

The cohort was derived retrospectively from linked administrative data for consumers' first admission to any of the five CCU sites in Queensland, Australia, between 2005 and 2014. Consumers were excluded if they did not meet the discharge criteria: a period of separation >28 days by 31 December 2014. Pre-admission measures covered the 365 days pre-admission; post-discharge measures covered the 365 days post-discharge. The Metro South Addiction and Mental Health Services Human Research Ethics Committee [HREC/15/QPAH/392] provided ethical clearance.

Measures

Dependent variables

The primary outcome was a change in mental health and social functioning, measured by the Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS; Wing et al., Reference Wing, Beevor, Curtis, Park, Hadden and Burns1998). The HoNOS is a 12-item clinician-rated questionnaire routinely used in outcome evaluation in Australia and internationally (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Pirkis and Coombs2015) with demonstrated validity, reliability (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Pirkis and Coombs2015; Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Harris, Coombs and Pirkis2017) and sensitivity to change (Slade et al., Reference Slade, Beck, Bindman, Thornicroft and Wright1999). Secondary outcomes were changes in: psychiatric service use (number of combined acute and non-acute, psychiatry-related bed-days, emergency department (ED) presentations); accommodation instability (number of changes in primary residence); involuntary treatment and disability (assessed using the Life Skills Profile (LSP-16) (Trauer et al., Reference Trauer, Duckmanton and Chiu1995)). The use of the HoNOS and LSP-16 in Australia is supported by an established national assessment protocol and training processes to facilitate inter-rater reliability (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Pirkis and Coombs2015). These measures are administered by clinicians at admission, 3-monthly review and discharge, with raters likely to differ across collection instances.

For HoNOS and LSP-16 the highest total scores (i.e. the poorest functioning/disability) recorded in the pre-admission and post-discharge period were used. This approach aimed to capture a picture of consumers' functioning in the community, rather than measurements at admission and discharge that may be impacted by the anticipated support at admission and relative stability at discharge. The change in psychiatric service use and accommodation instability was calculated by comparing the frequency between the 365 days pre-admission and 365 days post-discharge. The change in involuntary treatment status was determined by comparing status at admission and discharge from a CCU. In Queensland, mental health legislation permits involuntary treatment in both community and inpatient settings for consumers with a mental disorder requiring immediate treatment, with an associated imminent risk to self or others.

Independent variables

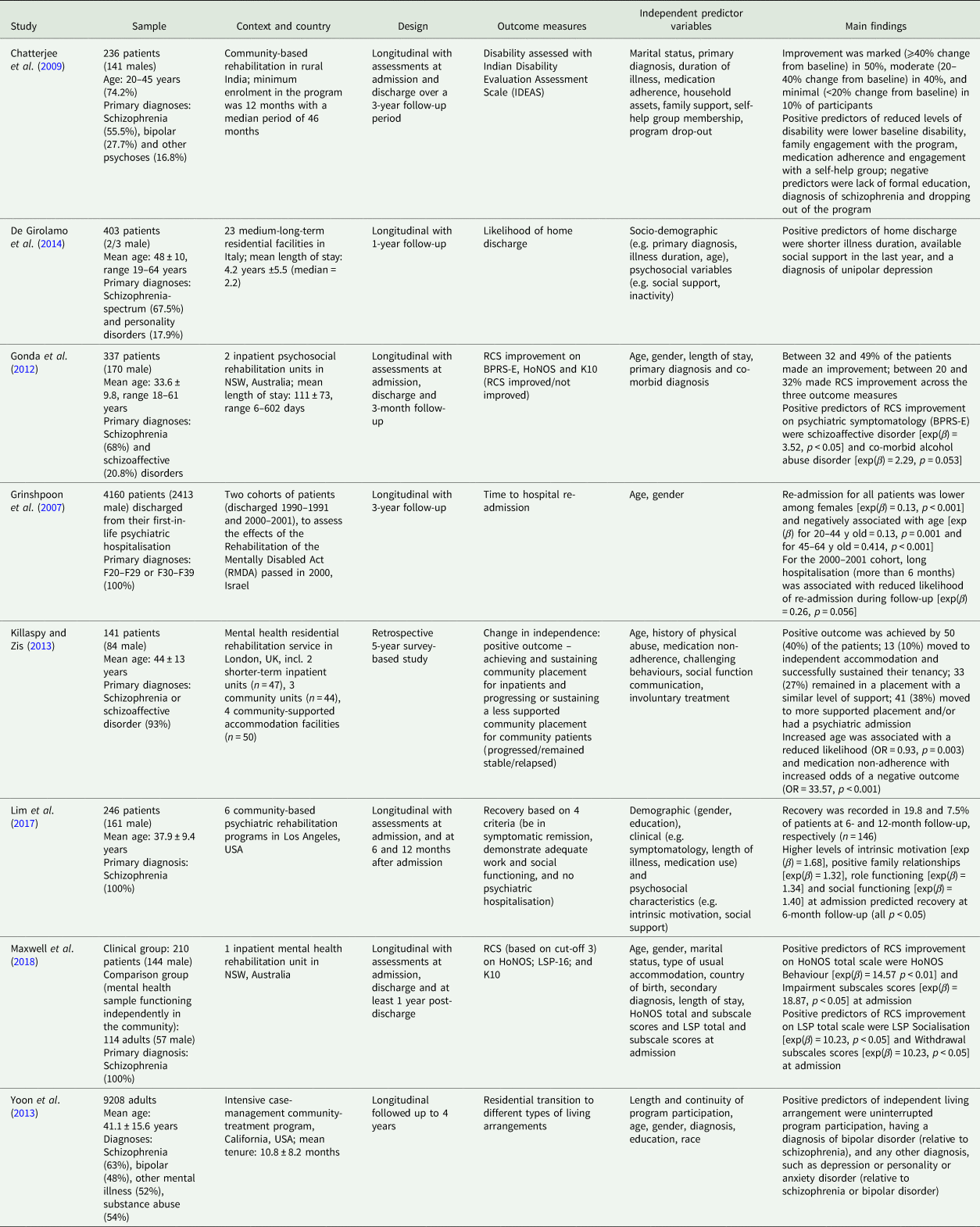

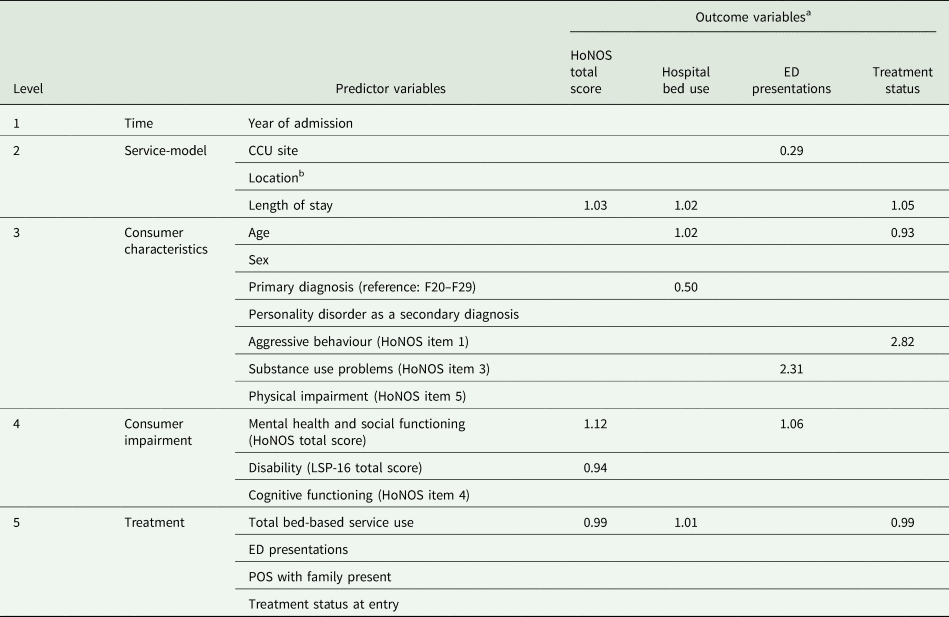

Based on the previous literature and the limitation of the data-set 18 potential predictors were organised across five levels (see Table 2): Level 1 – time (reflective of changes in service models over time); Level 2 – service-model (site/episode of care characteristics); Level 3 – consumer characteristics (more stable consumer features); Level 4 – consumer impairment (arising from Level 3) and Level 5 – treatment (to address impairments).

Table 2. A summary of statistically significant predictors (p < 0.05) across outcome variables based on the logistic regression analyses

CCU, community-care unit; HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; LSP-16, Life Skills Profile-16; ED, Emergency Department; POS, Provisions of Service.

a This table summarises the results of several logistic regression analyses that were conducted to facilitate consideration of the role of potential predictors across a range of outcome variables of relevance to rehabilitation care. The table presents standardised regression coefficients for statistically significant predictors of each outcome. See Table 5 for additional information.

b To compare CCUs across different locations, the postcode of each CCU location was classified into one of the ten decile rankings within Queensland, based on the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) 2016 (ABS, 2018). The locations of CCU sites corresponded to three separate rankings; one CCU was located within the 2nd ranking, two CCUs within the 8th and two CCUs within the 10th ranking.

Statistical analysis

Spss v25.0 (IBM, 2017) was used for all analyses.

Extent of improvement in outcomes

At a group level, differences between pre-admission and post-discharge scores were assessed using the Wilcoxon Signed-rank test for continuous variables, and the χ 2-square test for nominal variables. At the individual level, two indicators of change in outcomes were calculated, namely statistically reliable change and RCS change. To obtain the proportion of individuals with reliable change (i.e. improvement or deterioration) and those without reliable change (i.e. stable), the reliable change index (RCI), was calculated using the Christensen and Mendoza (Reference Christensen and Mendoza1986) formula:

s.e.diff is a measurement of a difference and was calculated as:

where s.d.1 is the standard deviation of the total score pre-admission and α is the Cronbach's coefficient of internal reliability of the outcome measure.

To assess the RCS change, a clinically significant change was first calculated, using three cut-off methods (Jacobson and Truax, Reference Jacobson and Truax1991):

• Cut-off 1: >2 s.d.s from the dysfunctional population mean;

• Cut-off 2: <2 s.d.s of the functional population mean and

• Cut-off 3: Closer to the functional population than dysfunctional population mean.

Cut-off 3 was calculated using the following formula:

The RCS change was assumed where the change between individual's pre-admission and post-discharge scores exceeded the RCI score and an individual's post-discharge score met any of the three cut-off criteria. These cut-offs were used to assess clinically significant change in HoNOS total scores. To calculate Cut-off 2 and 3, functional population data were derived from a study of 114 individuals residing in the community, accessing mental health services in New South Wales, Australia (Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018). Inclusion criteria for the functional population being: ⩾1 mental health-related inpatient or ED admission within the past 5 years, no psychiatric admissions within the past 6-months; low scores (⩽1) on HoNOS items 1 (overactive, aggressive, disruptive or agitated behaviour) and 6 (problems with hallucinations and delusions); primary diagnosis of a psychotic disorder and no documented admission to an inpatient rehabilitation unit.

For secondary outcome variables, Cut-off 2 and 3 could not be determined as functional population data were not readily available. Additionally, distributions of scores for secondary outcomes were too skewed, restricting the calculation of meaningful Cut-off 1 scores. Therefore, only the criterion of the statistically reliable change was considered.

Predictors of outcomes

Binomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate whether the proposed independent variables predicted significant changes in outcomes. Standard diagnostics were applied to test relevant assumptions and multicollinearity (online Supplementary Table 2). Sample homogeneity was explored based on admission year (2005–2009/2010–2015), CCU site, location, length of stay and primary diagnosis (F20.x-F29.x (schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders)/other disorders). Although several significant differences emerged, these were not considered of sufficient clinical relevance to warrant conducting analyses by sub-samples. The regression analysis was applied to outcomes where statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were present at a group level.

The primary outcome was dichotomised into ‘RCS improvement’ and ‘no RCS improvement’, using the cut-off identifying the greatest proportion of improved participants (Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012). Secondary outcomes were dichotomised into ‘reliable improvement’ and ‘no reliable improvement’. A hierarchical approach was followed due to expected inter-correlation between predictors (Scialfa and Games, Reference Scialfa and Games1987); variables were grouped into five levels and entered sequentially in blocks from Level 1 to Level 5 (see Table 2). Predictors at each level were retained in the model if they demonstrated a statistical significance in predicting a specific outcome (p < 0.05).

Results

Participant characteristics

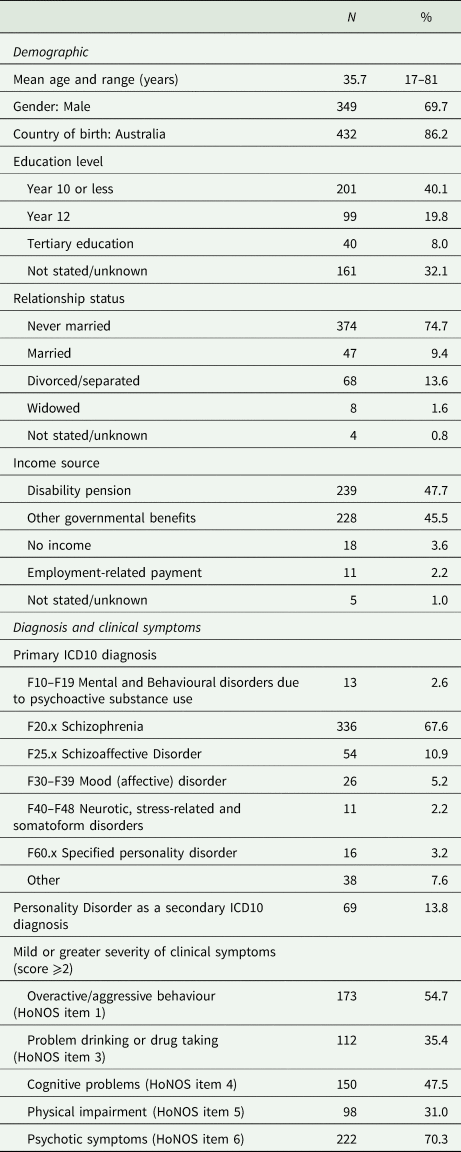

The sample included 501 participants (349 male) with a median CCU episode of care duration of 154 days (range 0–2225, one consumer being admitted and discharged on the same day). Demographic and diagnostic information is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Demographic and clinical characteristics of consumers prior to admission to a CCU (N = 501)

CCU, community-care unit; HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales.

Data were missing for Primary diagnosis (4 cases; 0.8%) and for all HoNOS items (185 cases; 36.9%). One subject was accepted for care and physically present in a CCU for part of a day but then discharged the same day.

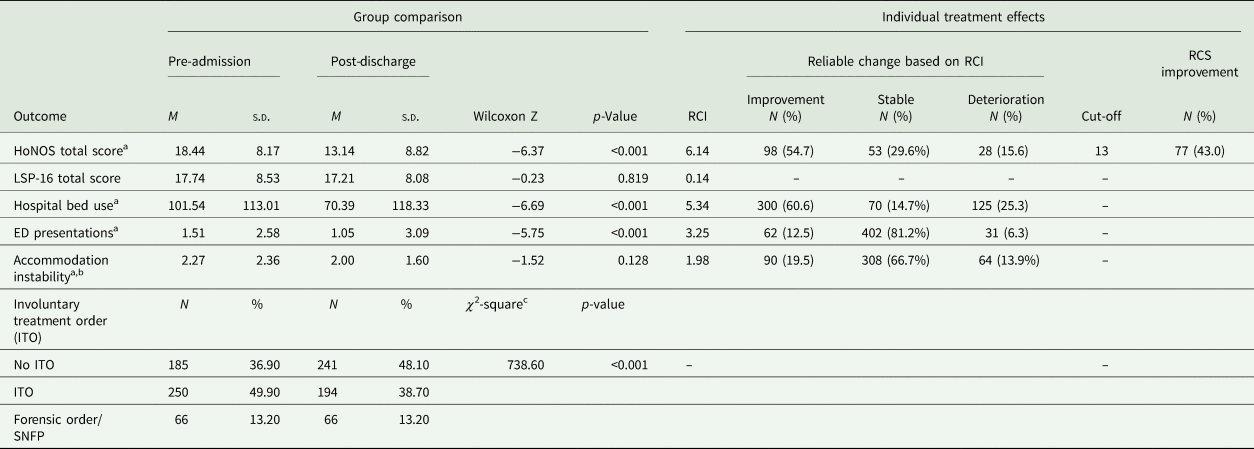

Summary of outcomes and modelling

Differences in outcome scores between pre-admission and post-discharge at a group level are presented in Table 4 (also online Supplementary Table 3). Assessments of the individual change were conducted on sub-samples of consumers with paired outcome data (179 for HoNOS, 237 for LSP-16, 495 for service use and 462 for accommodation instability). Statistically significant predictors of outcomes identified through logistic regression are summarised in Tables 2 and 5.

Table 4. Change in outcome variables between the 365 days pre-admission and 365 days post-discharge and classification of consumers based on criteria for reliable and RCS change (N = 501)

p, statistical significance; RCI, reliable change index; RCS, reliable and clinically significant; HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; LSP-16, Life Skills Profile-16; ED, Emergency Department; SNFP, Special Notification Forensic Patient.

Data were missing for HoNOS total score (185; 36.9% pre-admission and 292; 58.3% post-discharge), LSP total score (248; 49.5% pre-admission and 132; 26.3% post-discharge) and accommodation instability (6; 1.2% pre-admission and 2; 0.4% post-discharge). The number of paired observations assessed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and used to calculate the specific RCIs was 179 for HoNOS, 237 for LSP-16, 495 for hospital use and ED presentations and 462 for accommodation instability measures. The frequency of missing data for HoNOS and LSP-15 limited the sample sizes of complete paired data (35.73% and 47.30% of the total sample, respectively). Consumers with and without complete paired data on HoNOS total score were compared using the chi-square and Mann–Whitney U test to ascertain if data were missing at random; no significant differences (p < 0.05) were identified for length of stay at a CCU, sex, age, primary and secondary diagnoses, mild/greater severity of clinical symptoms (HoNOS items 1, 3, 4 and 5), LSP total score, hospital use, accommodation instability and involuntary treatment at admission to CCU. The groups differed (all p < 0.05) on HoNOS total score (M paired = 19.4, M others = 17.2), ED presentations (M paired = 2.1, M others = 1.3) and family involvement (M paired = 5.0, M others = 1.9).

a Consumers who died within 1 year since discharge (n = 6) were excluded from the analyses that included data referring to a 365-day time period post-discharge (i.e. hospital bed use, ED presentations and accommodation instability). However, these consumers were not excluded from the analysis of HoNOS data (three had complete paired data). Re-calculation of RCI without the six consumers produced the same cut-off score (6.82 rounded to 7) as the original analysis, meaning the proportion of improved consumers remained unchanged.

b To minimise the bias against consumers transitioning from long-term inpatient care to a CCU, consumers with more than 300 non-acute inpatient bed days (n = 28) were excluded from the analysis of accommodation instability.

c df = 4

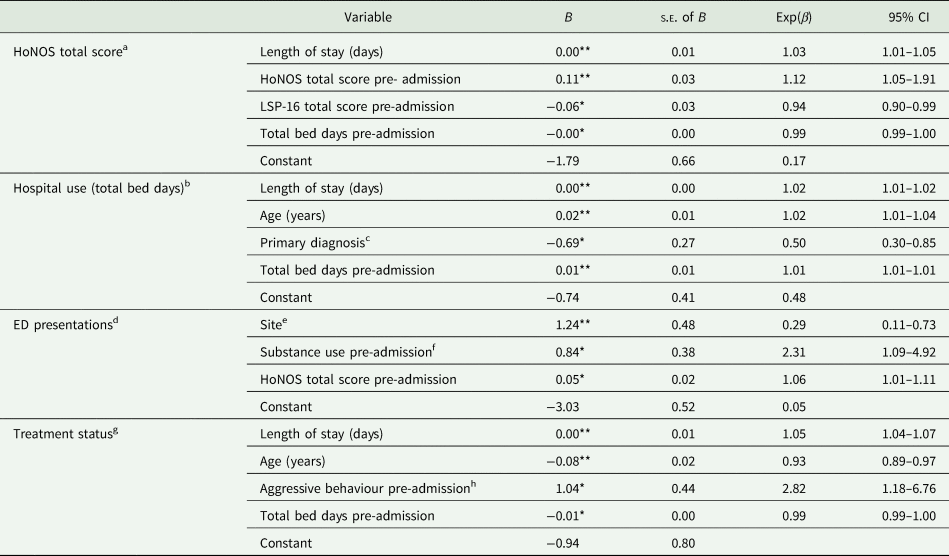

Table 5. Binary logistic regression predicting RCS improvement on HoNOS total score (n = 179), reliable improvement on service use (n = 495) and change towards a less restrictive treatment status between the year pre-admission and the year post-discharge (n = 501)

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; B, unstandardised regression coefficients; β, standardised regression coefficients; s.e., standard error; CI, confidence interval.

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

a The dependent variable is 0 = no RCS improvement and 1 = RCS improvement. The full model was significant (λ 2(4) = 20.00, p < 0.001); the model accounted for 17.7% (Nagelkerke R 2) of the total variance, correctly classifying 64.8% of consumers (44.8% as making RCS improvement and 78.6% as not improving).

b The dependent variable is 0 = no reliable improvement and 1 = reliable improvement. The full model was significant (λ 2(4) = 20.00, p < 0.001); the model accounted for 19.6% (Nagelkerke R 2) of the total variance, correctly classifying 65.8% of consumers (75.8% as making reliable improvement and 50.5% as not).

c The reference category is F20.x-F29.x.

d The dependent variable is 0 = no reliable improvement and 1 = reliable improvement. The full model was significant (λ 2(3) = 20.48, p < 0.001), accounting for 12.1% (Nagelkerke R 2) of the total variance; the model correctly classified 88.2% of consumers (2.6% as making reliable improvement and 100.0% as not).

e The reference category is a CCU site with 165 consumers (32.9%).

f HoNOS item 3 rating of moderate of higher pre-admission.

g The dependent variable is 0 = same or more restrictive status and 1 = less restrictive status. The full model was significant (λ 2(4) = 53.14, p < 0.001), accounting for 31.8% (Nagelkerke R 2) of the total variance. The model correctly classified 87.9% of consumers; 97.6% in the same or more restrictive group and 19.4% in the less restrictive group.

h HoNOS item 1 mild or greater pre-admission.

Mental health and social functioning

Consumers demonstrated significantly reduced HoNOS scores between the pre-admission and post-discharge periods (total and subscales). For HoNOS the RCI was 6.14 (rounded to 6); based on this, 54.7% reliably improved and 15.6% reliably deteriorated. In determining RCS change: Cut-off 1 (a score of 2) found improvement in 8.9% of consumers and deterioration in 2.2%; Cut-off 2 (a score of 13) found improvement in 43.0% of consumers and deterioration in 14.0% and Cut-off 3 (score of 9) found improvement in 32.0% of consumers and deterioration in 15.4%. For the hierarchical regression analysis, Cut-off 2 was used to dichotomise the sub-sample with paired outcome data into those with and without RCS improvement (43.0 and 57.0% respectively). RCS improvement was predicted by longer episodes of CCU care, as well as higher HoNOS total scores, lower LSP-16 total score and fewer psychiatry-related bed-days pre-admission.

Service use

Significant reductions occurred in acute and total psychiatry-related bed-days, but not sub-acute bed-days, following CCU discharge (Table 4 and online Supplementary Table 4). The RCI for total bed-days was 5.34 (rounded to 5), indicating that 60.6% of consumers reliably improved and 25.3% reliably deteriorated. For the regression analysis, the cohort was dichotomised into those making and not making a reliable improvement (60.6 and 39.4% respectively). Predictors of reliable improvement in total bed-days were longer CCU episode of care, increased age, higher total bed-days pre-admission and primary diagnoses other than schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder.

Significant reductions in ED presentations were identified at the group level. Using the individual-level data the RCI for ED presentations was 3.25 (rounded to 3). Reliable improvement was made by 12.5% consumers, while 6.3% showed reliable deterioration. For the regression analysis, the cohort was dichotomised into those who making and not making reliable improvements (12.5 and 87.5% respectively). Three statistically significant predictors of reliable improvement emerged: the presence of substance use issues (HoNOS item 3) and higher mental health and social functioning pre-admission (total HoNOS); and study site. Admission to one of the five CCU sites reduced the likelihood of improvement.

Accommodation instability

There were no statistically significant differences in accommodation instability from pre-admission to post-discharge. Using the RCI of 1.98 (rounded to 2), 19.5% consumers reliably improved (i.e. decreased the number of changes in primary residence) and 13.9% reliably deteriorated. When the 61 consumers who had transitioned from long-term in-patient care (i.e. no accommodation instability before CCU admission) were removed the difference between the mean number of changes pre-admission (2.61, s.d. = 2.34) and post-discharge (2.09, s.d. = 1.60) was statistically significant (n = 402, Wilcoxon Z = −3.85, p < 0.001).

Disability

There were no statistically significant changes in LSP-16 total scores between pre-admission and post-discharge.

Involuntary treatment

Statistically significant reduction in involuntary treatment between admission and discharge was identified. A total of 86.0% of consumers were discharged under the same treatment status; 12.6% were discharged under a less restrictive and 1.4% under a more restrictive treatment status. Logistic regression was conducted with the following two groups: less restrictive status (12.6%) and more restrictive/same status (87.4%). Four statistically significant predictors of the reduced likelihood of involuntary treatment emerged: longer episode of CCU care, mild-or-greater behavioural disturbance (HoNOS item 1) pre-admission, being younger and fewer pre-admission psychiatry-related bed-days.

Discussion

This study is the first published quantitative evaluation of contemporary community-based clinically-operated mental rehabilitation services in Australia. CCU care was followed by RCS improvement in mental health and social functioning for 43% of consumers. Consumers with poorer mental health and social functioning, and a longer episode of care were more likely to demonstrate RCS improvement. Additionally, many consumers experienced reliable improvements in relevant secondary outcomes. At the group level, significant improvements were observed when comparing the year pre- and post-CCU in mental health and social functioning, hospital bed days and ED presentations; but not accommodation instability and disability. Also, consumers were significantly more likely to be discharged with a less restrictive treatment status. These findings are generally consistent with the expected improvements following CCU care. However, the absence of change in disability was an important negative finding given the focus of care on the enhancement of independent living skills.

The observed reduction in HoNOS scores was consistent with previous studies evaluating rehabilitation service outcomes. The mean HoNOS score of consumers in the current study decreased by 4.9 points (from 18.4). This improvement is close to that observed by Macpherson et al. (Reference Macpherson, Calciu, Foy, Humby, Lozynskyj, Garton, Steer and Elliott2017), exceeds that reported by Barbato et al. (Reference Barbato, Agnetti, Frova and Guerrini2007), but was less than that observed in samples of rehabilitation patients with lower baseline severity (Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018). Different follow-up periods may be a factor affecting the magnitude of improvement observed across studies (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Barrio, Hernandez, Barragán and Brekke2017). It may be more appropriate to evaluate psychiatric rehabilitation services over longer periods given that these services focus on the improvement of social functioning in the community, which involves complex behaviours that are slow to change (Tsoutsoulis et al., Reference Tsoutsoulis, Maxwell, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018).

The finding of reduced mental health service use following rehabilitation care was also replicated (Grinshpoon et al., Reference Grinshpoon, Abramowitz, Lerner and Zilber2007; Tsoutsoulis et al., Reference Tsoutsoulis, Maxwell, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018). Compared to the year pre-admission, the average number of psychiatry-related bed-days in the year post-discharge decreased by 30 days (30.7%) and the number of ED presentations by 0.50 (30.5%). While our results corroborate positive trends in re-admission rates found in previous studies, it is important to acknowledge that service use is affected by system-related factors, such as access, availability and lack of alternative services.

The assessment of the individual change in consumers of CCUs revealed improvements in accommodation instability that were not detectable at a group level. A total of 19.5% of consumers made reliable improvements in accommodation instability from pre-admission to post-discharge. The failure to identify improvements at the group level was impacted by the absence of accommodation instability at baseline for 17.0% of the consumers included in the analysis. This finding highlights the relevance of focusing on individualised change criteria rather than group-based comparisons in mental health services research.

Methodological differences may explain the failure to replicate the improvements in disability (LSP-16) found in the Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018) study of an Australian inpatient rehabilitation service. Maxwell et al. (Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018) considered baseline and follow-up scores as the closest available data to admission and the first available data 12 months post-discharge. In contrast, we adopted a more conservative approach comparing the highest recorded disability in the 12 months pre- and post-CCU care. Regardless, the absence of observed improvement in disability suggests that CCU services may optimise clinical recovery more than functional recovery. The high frequency of chronic disability associated with a diagnosis of schizophrenia is well acknowledged (Galletly et al., Reference Galletly, Castle, Dark, Humberstone, Jablensky, Killackey, Kulkarni, McGorry, Nielssen and Tran2016), and efforts to address this should remain a focus of future research.

Measurement of the individualised change represents strength of this study. The proportion of consumers demonstrating RCS improvement is comparable to previous rehabilitation outcome studies using HoNOS (Barbato et al., Reference Barbato, Agnetti, Frova and Guerrini2007; Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012; Maxwell et al., Reference Maxwell, Tsoutsoulis, Menon Tarur Padinjareveettil, Zivkovic and Rogers2018). The use of local functional population data in the present study enhances the validity and generalisability of the findings to the Australian context. Analysis of the RCS change also identified that a minority of consumers deteriorate despite receipt of intensive rehabilitation care. Reliable deterioration occurred for 15.6% of consumers on HoNOS, and between 6.3% (ED presentations) and 25.3% (psychiatry-related bed-use) of consumers on secondary outcome measures. These adverse outcomes may relate to the stress and increasing demands associated with discharge (Gonda et al., Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012), loss of a supportive residential environment (Chopra and Herrman, Reference Chopra and Herrman2011) and factors impacting access to mental health services such as premature discharge due to disruptive behaviour (Stopa et al., Reference Stopa, Wang, Tyler, Brown, Sellwood, McKay, Dark and Parker2019). Reasons for discharge were not available, and further research to understand the profile of consumers who deteriorate despite receipt intensive rehabilitation support is warranted.

The current study also identified predictors of improvement among CCU consumers. Regression analysis indicated that RCS HoNOS score improvement was more likely among consumers with longer CCU admission length and those with higher baseline severity scores. In contrast, higher disability and psychiatry-related bed-use pre-admission were associated with a decreased likelihood of RCS improvement. Longer CCU admissions also predicted the reduced use of psychiatry-related beds and involuntary treatment. Additionally, decreased bed-use was statistically more frequent among older consumers, those with more bed-days before admission, and consumers with a diagnosis other than schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder. The latter finding corroborates previous studies, which found that a diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with poor rehabilitation outcomes relative to other diagnoses (Chatterjee et al., Reference Chatterjee, Pillai, Jain, Cohen and Patel2009; Yoon et al., Reference Yoon, Bruckner and Brown2013).

Unlike the findings by Gonda et al. (Reference Gonda, Deane and Murugesan2012) where the presence of a substance use disorder was an important predictor of symptomatic improvement, the only outcome which was predicted by this variable was a reliable improvement in the number of ED presentations. Additionally, we also found that a single site emerged as a negative predictor of reliable improvement in ED presentations. This suggests differential functioning amongst the study sites and support services in the areas where they are located. This finding highlights the importance of considering site-based variation and examining both process and outcomes in mental health services research (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Dark, Newman, Korman, Meurk, Siskind and Harris2016).

Cognitive impairment, a strong predictor of vocational rehabilitation outcomes for people affected by SPMI (Brune et al., Reference Brune, Schaub, Juckel and Langdon2011), did not emerge as a significant predictor in the present study. Explanations for this finding include possible divergence in the factors predictive of vocational rehabilitation and more general mental health rehabilitation and the inadequacy of using a single clinician-rated question as a measure of this construct. Future rehabilitation outcome studies would benefit from using more comprehensive cognitive assessments.

Limitations

The use of retrospective administrative data limited the variables available for analysis and data completeness (Connelly et al., Reference Connelly, Playford, Gayle and Dibben2016; Stewart and Davis, Reference Stewart and Davis2016). Adherence with routine outcomes monitoring protocols in Australia is known to be incomplete (Burgess et al., Reference Burgess, Coombs, Clarke, Dickson and Pirkis2012). All assessments of the individual change were calculated based on a restricted sample of those with complete paired data. This limits the extent to which these findings can be relied upon to be representative of the full cohort. Missing data also precluded the use of education history as a predictor in the regression analysis.

When drawing inferences based on the RCS change it is important to consider limitations of the outcome measures and the nature of the comparison group. For example, while HoNOS total score may not be elevated, individual subscales may still indicate a clinically significant impairment in specific domains (Parabiaghi et al., Reference Parabiaghi, Barbato, D'Avanzo, Erlicher and Lora2005). Additionally, the likelihood of the ‘regression-to-the-mean’ for consumers with more severe scores needs to be considered. Furthermore, recovery and community functioning are multidimensional constructs that are influenced by decisions at the micro (individual patient care) and macro (policy) levels (Tulloch et al., Reference Tulloch, Fearon and David2008). Caution is needed when interpreting secondary outcomes as these will be partly dependent on factors outside of the CCU.

The predictive models offer only a partial explanation for variability in the rates of consumer improvement. Data was not available for two known predictors from the rehabilitation literature: medication adherence and engagement with formal education. Given that formal education is compulsory for all Australian children aged 5–15 years (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Lyons and Quinn2014), the relevance of this variable appears less salient than medication adherence.

Finally, while controlling for several service-related variables (e.g. admission year, CCU site and length of stay), treatment-related data were not available regarding the specific therapeutic approaches received by consumers. Psychiatric rehabilitation is characterised by a mixture of practices and interventions, so information about the types of services received is critical to understanding best practice (Farkas and Anthony, Reference Farkas and Anthony2010). The present study provides support for positive outcomes following CCU service engagement, however, further work is required to identify active therapeutic processes that may facilitate positive outcomes.

Conclusion

Most consumers showed reliable improvement and 43.0% showed RCS improvement in mental health and social functioning following receipt of CCU care. Additionally, most consumers showed reliable improvements in psychiatric bed-use. Favourable outcomes were observed at the group level for a range of relevant secondary outcomes, with the exception of improvement in disability. The failure to observe improvements in disability suggests that these services may have a greater impact on clinical than functional recovery. Significant predictors of RCS improvement in mental health and social functioning were longer duration of stay at the CCU, lower baseline mental health and social functioning and disability, as well as lower psychiatry-related bed-use pre-admission. The current results add to the small but increasing body of literature providing support for positive outcomes following receipt of psychiatric rehabilitation.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796020000207.

Data

Further release of data would require approval from the relevant ethics committee and the relevant data custodians.

Acknowledgements

Professor Harvey Whiteford from the Queensland Centre for Mental Health Research provided advisory support to the research team. The Queensland Data-Linkage Unit collated the data-set.

Financial support

The Mental Health Alcohol and Other Drugs Branch (Queensland) funded UA's role in the project. DS is partially supported by NHMRC ECF APP1111136.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in preparing this work.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.