Introduction

Since its discovery in December 2019, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) remains one of the biggest global health challenges. To date, more than 38 million people have been infected by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which causes COVID-19 and more than 1 million people have died as a result of infection [1]. Children comprise roughly 10% of all the individuals infected with COVID-19 [2]. In Qatar, since the beginning of the pandemic in February 2020 up to April 2021, over 180 000 people have been confirmed to be infected with COVID-19, of whom a minority were children (aged 0–18 years old) [3]. As in other countries, there was a need in Qatar to define symptomatology in children to develop and implement school health policies and determine what constitutes a clinical case definition [Reference Badran4].

Although research suggests that children have a lower susceptibility to COVID-19 infection [Reference Dong5–Reference Brodin7] compared to adults, children can still get infected by the virus, and are capable of transmitting the virus to others [8]. Research also suggests that children are less likely to develop symptomatic infection and less likely to have severe disease, compared to adults [Reference Lee6, Reference Ludvigsson9]. Children have been indirectly affected by COVID-19 through many other ways such as through school closures in many countries [10–Reference Chang12]. The controversy about return-to-school policies remains unresolved though there is increasing evidence that transmission dynamics in children differed from that in adults [Reference Viner13, Reference Yonker14].

A first step towards understanding COVID-19 dynamics in children is to understand the nature of symptomatic infection in children, the predominant symptoms and how symptomatic infection differs by age [Reference Yoon15]. Available evidence to date has mainly been from China, where the pandemic is largely controlled [Reference Azman and Luquero16]. The prevalence of symptomatic infection in children was estimated to range between 9.7 and 27.3% [Reference Ding, Yan and Guo17]. Research suggests that infants less than 1 year of age have an increased risk of symptomatic infection, compared to other age groups, although this observation is not based on large representative studies [Reference Cui18, Reference Lu19]. Male children have also been found to be more likely to have asymptomatic infection, although these results are based on a systematic review of 158 cases only [Reference Yoon15]. Overall, the determinants of symptomatic infection are poorly understood. Therefore, in this study, we sought to estimate the prevalence of symptomatic infection and to describe the most common symptoms of COVID-19 in children with symptomatic infection and to investigate associated risk factors for symptomatic infection in children and adolescents aged 0–18 years.

Methods

Design and setting

A cross-sectional study of all children diagnosed with COVID-19 in Qatar during the period between 1st March and 31st July 2020 was carried out. Data on demographic information and clinical characteristics were obtained from the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), Qatar database. The national surveillance system ‘Surveillance and Vaccination Electronic System’ (SAVES) at the MoPH receives notifications from all healthcare facilities across the country, mainly from Hamad Medical Corporation (HMC) health facilities and Primary Health Care Corporation (PHCC). HMC and PHCC are the main non-profit public health care providers that manage 10 highly specialised hospitals, 27 PHCC health centres, as well as other governmental and semi-governmental health institutions. Children included in this study were consecutive cases tested either because they were symptomatic, contacts of other cases or if they were returned citizens or residents from travel. Trained health professional volunteers collected the data through a structured COVID-19 case investigation form developed by the MoPH based on best evidence that is currently available (WHO protocol) [20].

Study population

Children subjects diagnosed with COVID-19 aged 0–18 years old with laboratory confirmed SARS-COV-2 infection (i.e. PCR positive on nasopharyngeal swab) status between 1st March and 31st July 2020 were eligible for inclusion in the study.

Assessment of COVID-19 symptoms

Once the confirmed COVID-19 case was entered into the MOPH notification system, active case investigation was conducted by the MoPH surveillance team within 24–48 h using the case investigation form. Children were assessed for fever, cough, shortness of breath or difficulty breathing during the case investigations (children or parents were interviewed). In addition, for each case the team also collected data on age, nationality (Qatari/non-Qatari), ethnicity and clinical history. In addition, symptomatic infection was defined as the presence of any of a pre-defined list of possible symptoms during infection.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval (ERC-826-3-2020) and waiver of informed consent were given by the Health Research Governance Department at the MoPH. All data were deidentified before analysis.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were done for the presentation of baseline characteristics of the participants. Variables were summarised by the mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR) based on data characteristics. The t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test were applied to continuous variables while chi-square test was applied to categorical variables for differences between groups.

Age was categorised into three categories (<5, 5–9 and 10+ years old). Nationality was first grouped into Qatari vs. non-Qatari, and then it was further divided into seven ethnic categories based on geographical location: Middle East and North Africa (MENA), Asia, Africa, North America, Europe, South America and Oceania (Supplementary material).

A generalised linear model with a binomial family and identity link was used to assess the association between symptomatic infection and selected factors, including age, gender, nationality and mode of transmission (contact with a confirmed case in the last 14 days or visited a health facility within the last 14 days). The linktest was used to test model specification. The exact P-values were reported, and Stata MP version 15 (StataCrop, College Station, TX, USA) was utilised for all the analyses.

Results

A total of 11 445 children with COVID-19 were included in the analysis, summarised in Table 1. The sample had a median age of 8 years (IQR 3–13) and the distribution of children across age groups was almost one third in children aged < 5 years (30.9%) and 5–9 years (29.0%), and it was (40.1%) in children 10 years or older of the total. Amongst the total cases, approximately two thirds (66.7%) of the children infected with COVID-19 were non-Qatari and half (50.6%) of the children were males. Two thirds (66.0%) of the infected children had confirmed contact with a case diagnosed with COVID-19 within the last 14 days. In addition, there were no deaths reported among children in the sample.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of children with COVID-19 by symptomatic statusa

a Due to rounding percentages might not add up to 100%. Median (IQR) is reported for continuous data and n (%) for categorical data.

b Four nationalities were unknown.

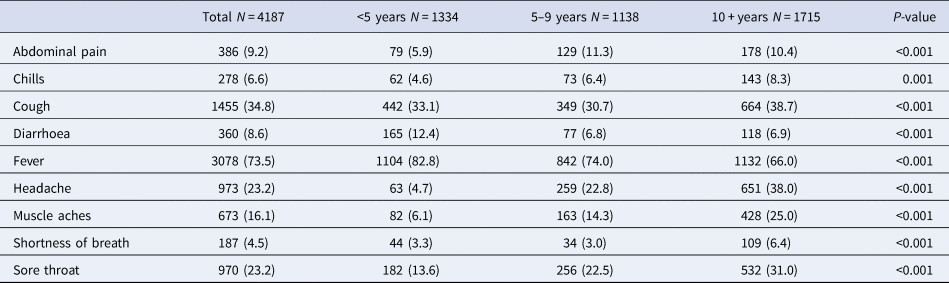

The prevalence of symptomatic COVID-19 was 36.6% (95% CI 35.7–37.5), and it was similar in children aged <5 years (37.8%), 5–9 years (34.3%) and 10 years or older (37.3%). Moreover, regarding the prevalence of clinical manifestations in children with symptomatic infection, fever (73.5%) and cough (34.8%) were the most prevalent symptoms, whereas chills (6.6%) and shortness of breath (4.5%) were less common (Fig. 1). Similarly, across the entire age groups, fever and cough were the most common symptoms, while shortness of breath was the least prevalent. In particular, fever (82.8%) was more common in symptomatic children aged <5 years, while cough (38.7%) was more prevalent in those aged 10 years or older, compared to other age groups (Table 2). When clustered by type of symptom, only pain (headache, musculoskeletal pain and abdominal pain) increased with age, whereas gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory and other infection-related symptoms were similar across all age groups (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Prevalence of symptoms in symptomatic children with COVID-19.

Fig. 2. Proportion of symptoms by age groups.

Table 2. Comparison of symptoms in 4187 children with symptomatic COVID-19 by age group

Multivariable analysis (Table 3) revealed that the baseline symptomatic proportion in children with no contact history, no visit to the health care facility, of Qatari status and of age 5–9 years was 15.0%. Children aged below 5 and 10–18 years had an increased symptomatic proportion of 5.0% [risk difference (RD) 0.05; 95% CI 0.02–0.07; P < 0.001] and 4.0% (RD 0.04; 95% CI 0.02–0.06; P < 0.001) respectively compared to age 5–9 years. Non-Qatari children also had an increased symptomatic proportion of 5.0% (RD 0.05; 95% CI 0.04–0.07; P < 0.001) compared to Qatari children. Both contact with a confirmed case (RD 0.21; 95% CI 0.20–0.23; P < 0.001) and visit to a health care facility (RD 0.54; 95% CI 0.45–0.62; P < 0.001) were associated with a markedly increased symptomatic proportion compared to those without a contact history. However, there was an antagonistic interaction between the latter such that both contact with a confirmed case and visit to a health facility together decreased symptomatic proportions by 41.0% over the expected additive increases associated with both exposures.

Table 3. Factors associated with symptoms in children with COVID-19a

a Generalised linear model with binomial family, identity link and RD as the effect measure. Children aged 5–9 years, Qatari, males, no-contact and no-visit were the reference groups with baseline risk of being symptomatic being 0.15 (constant in the regression model). The RDs in this analysis are not transferable beyond the data presented here, however, the trend can be generalised to other paediatric populations.

Discussion

We found that almost one-third of children with COVID-19 infection were symptomatic, in a large cohort of children aged from the first year of life through to the age of 18 years. Almost three-quarters of the children with symptomatic COVID-19 infection had fever, and perhaps this could be due to a higher viral load while cough was the second most commonly reported symptom, but with just over one-third of children reporting this. In addition, pain was mainly limited to older children, perhaps children in this age group are better to communicate this symptom. Children of ages <5 (31.9%) and 10+ years (41.0%) had a higher risk of being symptomatic (these are higher percentages than reported in Table 3 because they include children with contact history). Indeed, contact with a confirmed COVID-19 case, and visiting a health facility in the 2 weeks prior to the diagnosis of COVID-19 significantly increased the risk of having symptomatic COVID-19 infection, which could be explained as an effect−cause situation.

In the current study, the prevalence of symptoms in low-risk children (no contact history, no visit to a health care facility, Qatari status and age 5–9 years) was 15.0%. The prevalence of COVID-19 symptoms was found to be about double of this baseline in the whole population of children (36.6%). However, several studies contradict this finding [Reference Lu19, Reference Laws21–Reference Hoang23]. For example, Hoang et al. reported around 80.0% prevalence of symptomatic infection across 131 studies [Reference Hoang23]. Similarly, another meta-analysis study showed 84.0% of symptomatic infection among infected children [Reference Assaker24]. This disparity could be a consequence of very small sample sizes and selection of sick children into previous studies.

Prevailing symptoms in children with symptomatic COVID-19 was topped by fever (73.5%) and was followed by cough (34.8%). This was also consistent with several reports [Reference Chang, Wu and Chang22–Reference Zachariah32]. For instance, in a study of 7780 children with COVID-19, fever (59.1%) and cough (55.9%) were the symptoms most frequent reported [Reference Hoang23]. Moreover, Giacomet et al. also found fever (79.4%) and cough (48.6%) more common [Reference Giacomet30]. Shortness of breath was the least prevalent symptom (4.5%) reported in this study, and the finding was contrary to some previous reports [Reference Lu19, Reference Laws21, Reference Chang, Wu and Chang22, Reference Assaker24, Reference Bialek26, Reference Zare-Zardini33]. For example, abdominal pain (8%) was the least frequent in a meta-analysis of 1614 infected children [Reference Assaker24]. A retrospective study conducted by Lu et al. also reported musculoskeletal symptoms (2.7%) were least common in 110 children with COVID-19 [Reference Lu19]. Another review study also found chest pain (0.4%) to be least prevalent [Reference Zare-Zardini33]. This discrepancy could have several reasons. Firstly, two of the studies reporting symptoms were meta-analyses [Reference Chang, Wu and Chang22, Reference Assaker24] and one was a review [Reference Zare-Zardini33] and thus heterogeneity of results is expected. Secondly, two studies included subjects with comorbidities [Reference Laws21, Reference Bialek26], which might be a source of variation among symptoms reported as children with chronic conditions are more likely to get severely ill. In addition, rather than depend solely on the database, in this study the symptomatic status was ascertained through phone calls with the parents.

This study found that children of less than 5 years and 10 or more years of age were more susceptible to symptomatic COVID-19 infection, compared to children aged 5–9 years. Similar findings were also reported in China [Reference Lu19, Reference Dong34] but so far the exact reasons behind this phenomenon remain unknown.

The current study indicated approximately two thirds of the children infected had a contact with a COVID-19 confirmed case (66.0%) but very few had visited a health care facility (about 5.0%), which is consistent with several previous studies [Reference Qiu27, Reference Cai29, Reference Xiong35]. For instance, Qiu et al. reported that the majority of the children infected had a history of exposure to a family member with confirmed status of COVID-19 [Reference Qiu27]. In addition, a meta-analysis of nine case series indicated that 75.0% of the infected children had a direct contact with a COVID-19 case [Reference Chang, Wu and Chang22]. Another study reported that 63.0% out of 68 infected children had contact with a confirmed case [Reference Laws21]. In this study, symptomatic status was 21.0% more in those with contact history and 54.0% more in those with health system visits. However, when both occurred together, the expected increase should have been 75.0% (54 + 21%) but due to the antagonistic interaction this was only 34.0% (75–41%; see Table 3) suggesting that many patients with both contact and a health system visit were asymptomatic.

The main strength of this study, is that it is the largest population-based study of COVID-19 infection among children to date. This study also has some limitations. Firstly, this study was a cross-sectional study, which does not assess causal relationship, but rather generates hypotheses. Secondly, our study was limited to available MoPH data. Data on comorbidities and hospitalisation need further study to gain further insights on the evolution of symptoms and clinical course of COVID-19 infection in children.

In conclusion, a third of the children with COVID-19 are symptomatic with a higher proportion of symptomatic infection in children at the two extremes of age. Fever is the predominant symptom in symptomatic children and a clear contact in the community or a visit to hospital markedly increases the possibility of a symptomatic infection.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268821001515

Acknowledgements

We thank all the investigation and contact tracing teams at MOPH and HMC and the Primary health care centre.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: OM, TC and SD were responsible for study conception and provided statistical input. Methodology: OM, TC, DB, EF planned and designed the study. Data curation: OM, DB, HA, AM, JA, SA, HK, SH, MN, MA, EF and AE contributed to the data acquisition. Analysis: OM conducted the analysis with TC and SD support. Writing-original draft preparation: OM drafted the manuscript with OA, NI, DB and TC support. Writing-reviewing and editing: SD, XC and LFK critically reviewed the manuscript for clinical applicability and relevance and provided epidemiological and statistical oversight, and all authors reviewed the manuscript for scientific content. MHA and EF are the guarantors of the study. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. LFK was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Fellowship (APP1158469).

Conflict of interest

None.

Data availability statements

The data that support the findings will be provided upon request.