Introduction

Vertebral osteomyelitis (VO), also named infectious spondylodiscitis, is the infection of an intervertebral disc and at least one adjacent vertebra. It is associated with considerable morbidity, disability and extra costs [Reference Zimmerli1–Reference Kowalski5]. Haematogeneous dissemination represents the main infection process (60–80%) while direct and local inoculation following a spinal surgery, a lumbar puncture or an epidural injection is less frequent (15–40%) [Reference Zimmerli1, 6]. Clinical presentation is often characterised by non-specific symptoms (back pain, back stiffness, fever), especially within the elderly with multiple comorbidities [Reference Zimmerli1, 6]. Following a recent spinal surgery, local scarring signs are commonly observed [Reference Kowalski5]. VO is a serious infection requiring a hospital management, an antibiotic treatment and a potential surgical treatment [Reference Zimmerli1, Reference Kowalski5, 6].

Since several years, many studies suggested an increase in VO incidence in Western countries [Reference Grammatico-Guillon3, Reference Doutchi7–Reference Akiyama11]. This might be explained by the increasing number of comorbidities in those countries, especially among the ageing population, or by an improvement in the diagnosis of VO [Reference Kehrer10–Reference Kumar12]. Indeed, an enhancement in imaging techniques and higher availability of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could have improved the diagnosis of VO [Reference Doutchi7, Reference Kehrer10, Reference Kumar12]. The French infectious diseases society (SPILF) lastly updated its guidelines in 2007, potentially leading to better management of patients with suspected or confirmed VO in France [6]. It was followed by the American society (IDSA) in 2015 then by three European societies (EANM, ESNR and ESCMID) in 2019 [Reference Berbari13, Reference Lazzeri14].

In the light of these evolutions, updating the epidemiology of VO in France appeared to be a necessity to better understand the patients with VO and the consequences regarding their hospital management. The study aimed to assess the evolution of VO incidence in France over the last decade and describe the patient outcomes using the French hospital discharge databases.

Methods

Study design

A nationwide cross-sectional study was conducted over the 2010–2019 period, using the French hospital discharge (HD) data available on the national secured website of the Agence Technique de l'Information Hospitalière (ATIH). VOs were detected with a previously validated algorithm developed from the French diagnosis-related groups (DRG) Programme de Médicalisation des Systèmes d'Information (PMSI), giving a 94% predictive positive value [Reference Grammatico2].

This national HD database is based on the mandatory notification of each hospital stay for all public or private hospitals. All hospitalisation information is stored in a coded summary using the International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD-10) and the French current procedural terminology (CPT). All patients are assigned a unique identification number, allowing the same individual to be followed over time.

Study population

Patients aged 15 years old (y.o.) or older meeting the criteria of the validated VO case definition (Supplementary data 1A) in their hospital resume over the 2010–2019 period were included. Indeed, we selected any HD with a principal or secondary diagnosis of VO appearing alone or in combination with either sepsis or a specific surgical procedure. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes included spondylodiscitis and infectious complications of surgical care (T codes). The surgical procedures according to the French Common Classification of Medical Acts (French CPT) included debridement, prosthesis removal, exchange or revision. Device-associated VO (DAVO) was defined as a VO with the presence and/or withdrawal of a spinal orthopaedic device (Supplementary data 1B).

We linked multiple hospitalisations to anonymised patient data, using a unique and encrypted patient number, in order to obtain the patient database. HD data were used to describe VO, whereas the patient database was used to describe the epidemiology of VO cases.

Data analyses

Overall VO incidence was estimated by dividing the number of VO cases by the French population aged 15 y.o. or older over the decade, as estimated by the French Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques (INSEE) and stratified by age and sex. VO incidence per year was estimated by dividing the number of VO cases during 1 year by the French population of the year.

Patient-related data included socio-demographics, comorbidities coded during the hospital stay (Supplementary data 2) and in-hospital mortality. An elderly patient was defined as a patient aged 65 y.o. or older.

Hospital stay-related data included the length of stay, healthcare sector (public or private), microbiological and antibiotic resistance codes and severity of the clinical presentation [severe sepsis, admission in intensive care unit (ICU)]. Hospital stays in reference centres for complex bone and joint infections (BJI) or presenting the specific ICD-10 code for complex BJI (Z 76 800 assigned after validation from a multidisciplinary team) were also described as previously studied [Reference Laurent4]. Patient and hospital stay costs were described without adjustment.

Data were described according to their number and rate for qualitative variables and according to their mean, median, minimum and maximum for quantitative variables, as well as quartiles, fifth and 95th percentiles for hospital length of stay and costs. The analysis was first conducted for the overall study population, then specifically among DAVO hospital stays. No statistical test was performed, as all comparisons were likely to be statistically different regardless of clinical significance and the PMSI discharge database is exhaustive.

Ethic statements

The study was performed in accordance with the French Reference Methodology MR-005 for retrospective studies using PMSI, elaborated by the French authority Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés (CNIL). It was registered on the Health Data Hub, number F20210121134244.

Results

During the study period, 42 105 patients aged 15 y.o. or older were hospitalised for VO in France (Fig. 1), involving 60 878 hospital stays (mean 1.43 hospital stay per patient). The patients were mainly male (60.9%), mean age was 64.8. Among them, 3059 (7.3%) died during their VO stay. Nearly 10% had a DAVO (N = 3881) (Table 1).

Fig. 1. Flow chart of the study population (adult patients with vertebral osteomyelitis VO).

Table 1. Characteristics of vertebral osteomyelitis (VO) patients

Incidence evolution and patient description

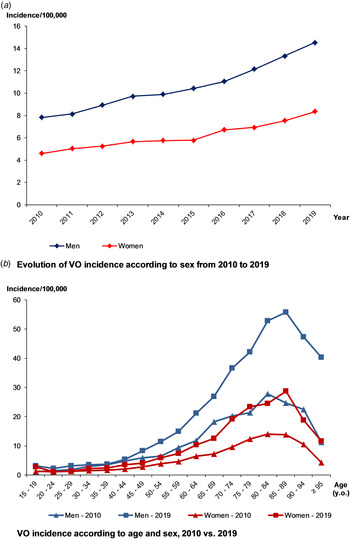

Over 2010–2019, VO incidence was 7.8/100 000, higher in males than females (10.0/100 000 vs. 5.9/100 000). Over the decade, it nearly doubled, from 6.1/100 000 to 11.3/100 000 (+84%) (Fig. 2a) and was higher in the elderly (Fig. 2b). The maximum incidence was observed for people aged between 75 and 90 y.o., regardless of the gender or the year. When focusing on residency areas and administrative French regions, we also observed heterogeneity of incidence rate, after standardisation on age and sex. However, whatever the region, an increasing incidence rate was observed over the decade, comparing the two periods of 5 years (Supplementary data 3).

Fig. 2. Evolution of the incidence of vertebral osteomyelitis (VO) over the decade, by age and sex.

Three-quarters of the patients had one or more comorbidities, and 30.2% had three or more (Table 1). Cardiovascular diseases were the most common comorbidities (39.7%), followed by diabetes mellitus (19.8%). Kidney failures (15.4%), urinary tract infections (14.8%), cancers (13.7%) and obesity (10.2%) were also commonly identified.

Also, 2102 patients (3.5%) had severe sepsis and 1414 (2.3%) were hospitalised in ICU. Endocarditis was retrieved in 11.5% of the patients.

Hospital stay characteristics and evolution

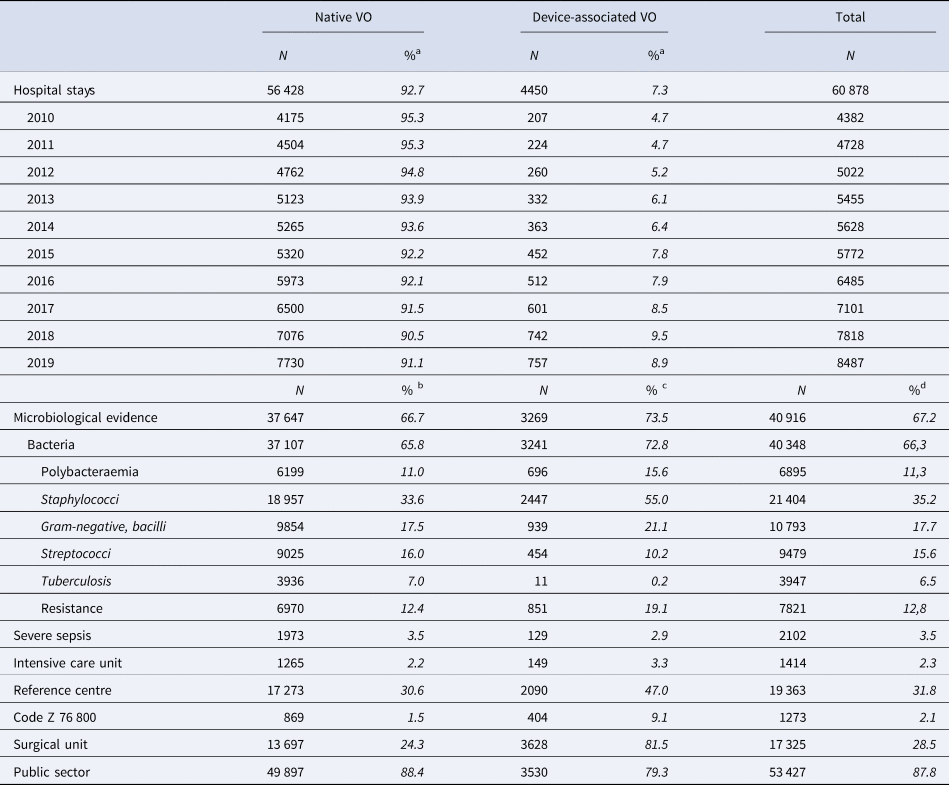

During the study period, there were 60 878 adult VO hospital stays, increasing each year and nearly doubling between 2010 and 2019, from 4382 in 2010 to 8487 in 2019 (+94%) (Table 2). Most of the hospital stays (87.8%) occurred in a public healthcare facility, 31.8% occurred in a reference centre for complex BJI and 28.5% in a surgical unit.

Table 2. Characteristics of the hospital stays for vertebral osteomyelitis (VO)

a % of all VO of the current year.

b % of native VO.

c % of device-associated VO.

d % of all VO.

A microorganism was coded in 40 916 hospital stays (67.2%). Gram-positive cocci were the most frequent bacteria: 21 404 Staphylococci (52.3% of hospital stays with microbiological codes) and 9479 Streptococci (23.2%). Gram-negative bacilli were found in 10 793 hospital stays (26.4%) and tuberculosis in 3947 (9.6%) (Table 2).

DAVOs remained rare (4450 hospital stays, 7.3%) (Table 2), but highly increased in both number and rate over the period. Most of them required hospitalisation in a surgical unit (81.5% vs. 28.5% of all VO hospital stays). As compared to native VOs, hospitalisation in a reference centre and hospitalisation in a private healthcare facility were more frequent among DAVOs. DAVOs were less often associated with severe sepsis than native VOs, but more often admitted to ICU. A microorganism was more often coded in DAVOs than in native VOs (73.5% of the DAVOs): Staphylococci were the most common followed by Gram-negative bacilli while Streptococci were less frequent. Polybacteraemia and antibioresistance were also more frequent (Table 2).

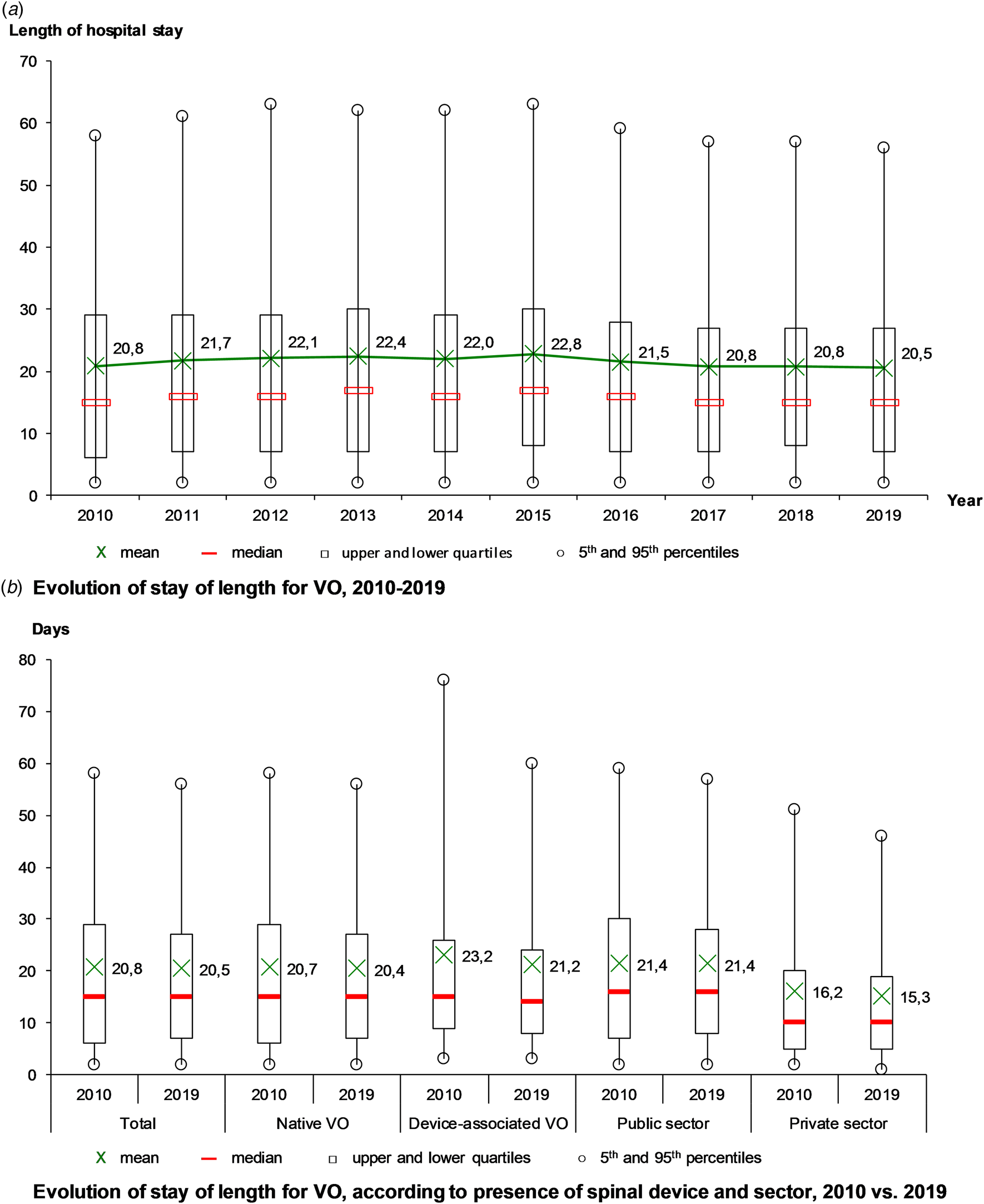

The mean length of stay was 21.4 days, stable from 20.8 days in 2010 to 20.5 days in 2019, with a maximum in 2015 (22.8 days) (Fig. 3a). Over the decade, the mean length of stay decreased for DAVO (from 23.2 to 21.2 days), especially for the longest stays (from 77 to 60 days in the 95th percentile) and in the private sector (from 16.2 to 15.3 days) (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. Evolution of hospital stays for vertebral osteomyelitis (VO) over the decade, France.

The mean cost of VO hospital stay was 10 798 euros. It gradually increased from 9955 euros in 2011 to 10 950 in 2019, regardless of inflation. The mean cost for DAVO remained stable at around 13 000 euros per stay. However, it decreased in very expensive stays (from 31 619 to 27 495 euros in the 95th percentile). As compared with the public sector, these crude costs were about twice as low in the private sector, but slightly increased over the study period (from 5020 to 5462 euros).

Discussion

VO incidence increased in France from 2010 to 2019, rising from 6.1/100 000 to 11.3/100 000, predominantly in elderly men with multiple comorbidities. This study highlighted the frailty of VO patients and the substantial increase of DAVO. Our study is one of the first to date to use a large real-life database with the completeness of the cases collection, allowing an accurate estimation of the incidence. A similar increase in VO incidence has been found in Western countries [Reference Grammatico-Guillon3, Reference Doutchi7, Reference Issa9–Reference Akiyama11]. In another Japanese study using an administrative database over a 4-year period, an increasing trend was found with a VO incidence rising from 5.3/100 000 population per year in 2007 to 7.4/100 000 population per year in 2010 [Reference Akiyama11]. In a US epidemiological study over 15 years, the incidence of VO admission was 4.8 per 100 000, increasing from 8021 cases (2.9/100 000) in 1998 to 16 917 cases (5.4/100 000) in 2013 [Reference Issa9]. Moreover, in a population-based study, focused on 1995–2008 pyogenic VO in a Danish county, the overall incidence increased from 2.2 to 5.8 cases per 100 000 person-years [Reference Kehrer10]. The main hypotheses to explain this evolution could be the frailty of the ageing population and the improvement in VO diagnosis [Reference Doutchi7, Reference Issa9–Reference Akiyama11]. Indeed, in France in 2007, the SPILF guidelines update for VO diagnosis and management probably led to better clinical awareness and understanding, which are key determinants to improve diagnosis and could be linked to an incidence increase [6]. The more systematic use of MRI for patients with compatible clinical signs, even with more subtle presentation as in elderly for whom back pain and stiffness are non-specific, may have taken part in this increase [Reference Doutchi7, Reference Kehrer10, Reference Kumar12]. Indeed, a recent Spanish retrospective study suggested an increased diagnosis of VO with subtle clinical presentation, which was more frequently associated with the absence of microbiological evidence and a more prominent role of less virulent bacteria [Reference Lora-Tamayo8]. However, caution must be taken in interpreting these findings, especially in the elderly for whom it could be challenging to differentiate VO and erosive degenerative disc diseases, potentially leading to over-diagnose VO [6].

Our study showed that patients with VO were more likely to be male, aged and frail, as estimated in other Occidental studies [Reference Doutchi7, Reference Issa9, Reference Kehrer10]. Indeed in the Danish study, the elderly had the highest incidence compared to those aged ≤70 years (rate ratio for men 5.9 [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.2–8.5] and for women 3.5 (95% CI 2.3–5.3)) [Reference Kehrer10] as in the Japanese study where 58.9% of VO patients were men and the average age was 69.2 years [Reference Akiyama11]; whereas a majority of patients of the US epidemiological database study from 1998 and 2013 were male (51%) and younger than 59 years of age (49.5%) [Reference Issa9]. In Western countries, both life expectancy and mean age are increasing [Reference Jakovljevic and Laaser15, Reference Le Cossec16]. However, VO incidence was also increasing in every age group, so the ageing of the population cannot explain these results by itself. Most of the patients had comorbidities, which increased from 2010 to 2019. These evolutions should be interpreted in the light of the coding process that became more comprehensive and efficient because of its professionalisation in France and a financial incentive. However, the main comorbidities we identified are already known as diseases with an increasing prevalence over the last decades like in previous international studies, including diabetes mellitus, cancer, intravenous drug use, alcoholism or cirrhosis [Reference Doutchi7, Reference Issa9, Reference Kehrer10, Reference Palladino17]. Eventually, the differences we observed among French regions suggest that environmental and demographic factors may have taken part in these evolutions. Though, our study design could not allow us to identify these factors.

A substantial increase in the incidence of DAVOs has been retrieved. Even if starting from an extremely low number in 2010, the DAVO rate nearly doubled over the decade. A parallel increase in spinal surgeries is observed in many Western countries, in order to face the rising demand for functional surgery especially concerning degenerative and non-traumatic spinal diseases in the elderly [Reference Kowalski5, Reference Deyo, Nachemson and Mirza18–Reference Deng20].

The microbiologically confirmed VO rate remained stable as compared to the previous studies using PMSI [Reference Grammatico2, Reference Laurent4], even with the SPILF guidelines recommending a more active seeking for microbiological diagnosis. Other European studies found the same stability of microbiologically confirmed VOs over recent years [Reference Kehrer10, Reference Avenel21].

The 2007 French guidelines recommended to reduce the duration of immobilisation in non-complicated VOs [6]. Also, a recent clinical trial suggested that the duration of antibiotic treatments and supine position could be shortened [Reference Bernard22]. Thus, a faster discharge home and a decrease in the length of stay were expected. Yet, the mean length of stay decreased by 4 days compared to the 2002–2003 study but it remained quite stable over the decade [Reference Grammatico2]. Still, we observed a decrease in long hospital stays which were more likely to concern severe or complicated VO cases, suggesting better management of these cases.

This study has some limitations, notably, the controversial issue concerning the reliability of the coding system, as data are coded by different healthcare professionals [Reference Grammatico2, Reference Grammatico-Guillon3, Reference Lipsky23]. VO may be perceived more relevant by physicians, and so priority coded in the discharge resume, than others such as microbiological evidence. However, variation of coding practice was assessed amongst medical practitioners [Reference Grammatico-Guillon24], providing strong predictive values. Recent studies used robust medical information systems in association with surveillance network data and obtained good results with a sensitivity/specificity and predictive positive value of 95%, 99% and 84%, respectively [Reference Grammatico-Guillon3, Reference Inacio25]. In our study, the algorithm for defining a VO case was built by a multidisciplinary team using different combinations of codes of interest for spine-related infections hospital stays. This kind of data reuse for epidemiological purposes has shown robust performance for the detection and surveillance of numerous diseases [Reference Grammatico-Guillon3, Reference Issa9, Reference Kehrer10, Reference Lipsky23]. Another limit of our study was that we could not identify infection sources and processes (haematogeneous or local) through the PMSI data. We also found limits in using a medico-administrative database, especially concerning the identification of factors explaining these evolutions. For instance, the deprivation status of the patients could not be retrieved in the study design, whereas it could potentially enhance the frailty, a key determinant of VO occurrence.

Despite some limits, HDD-based surveillance could be promoted as a cost-effective method for routine surveillance, especially in infectious diseases. The validated algorithm represented one of the main strengths of the study by providing an exhaustive and real-life review of VO cases to compare VO incidence over time. Using the same method over the decade, an update of the VO epidemiology was performed [Reference Kumar12]. As compared to the 2002–2003 results [Reference Grammatico2], VO incidence was 2.8/100 000, 6.1 in 2010 and 11.3 in 2019 in the current study. Even though ICD-10 and procedures codes for DAVOs were not included in the initial algorithm, the 2002–2003 VO incidence was probably not underestimated, as these DAVOs were most probably coded along with overall VOs. Cost-benefit analysis and studies combining multiple hospital databases are furthermore warranted and an automated surveillance system could be thought, especially to improve an analysis of the potential explicative factors that the HDD could not identify.

To conclude, our study outlined the high increase in VO and DAVO incidence in France over the 2010–2019 decade, similarly to other Western countries. The reliability of the method, based upon an exhaustive database and a validated case definition, provided an effective tool to compare data over time in real-life conditions to regularly update the epidemiology of VO. It also highlighted the potential need for an update in the current French guidelines, especially concerning epidemiological and microbiological diagnosis trends.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268821002181

Acknowledgements

No other individual or organisation provided support to this work.

Authors contribution

Yoann Conan: Formal analysis, writing − original draft, visualisation. Emeline Laurent: Conceptualisation, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing − original draft, supervision. Yannick Belin: Methodology, formal analysis, data curation, writing − original draft, visualisation. Marion Lacasse: Writing − review & editing. Aymeric Amelot: Writing − review & editing. Denis Mulleman: Writing − review & editing, validation. Philippe Rosset: Writing − review & editing, validation. Louis Bernard: Writing − review & editing, validation. Leslie Grammatico-Guillon: Conceptualisation, methodology, validation, writing − original draft, supervision.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Data are available on the national secured website of the ‘Agence Technique de l'Information Hospitalière’ (ATIH : https://www.atih.sante.fr/) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Conflict of interest

None.