No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

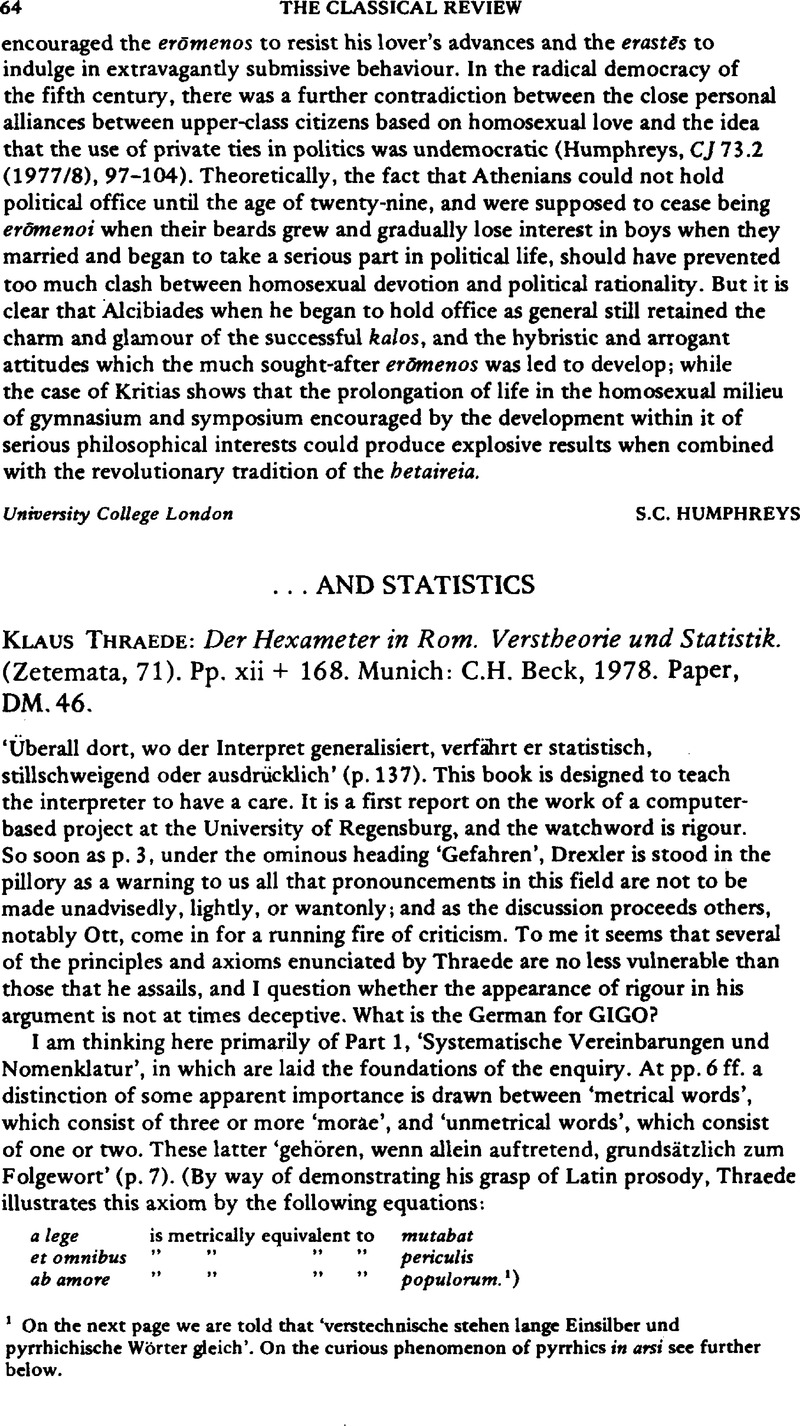

1 On the next page we are told that ‘verstechnische stehen lange Einsilber und pyrrhichische Wörter gleich’. On the curious phenomenon of pyrrhics in arsi see further below.

2 e.g. at Aen. 1.645 ‘Ascanio ferat haec ipsumque ad moenia ducat’, the metre is not felt as irregular because ferat baec cohere syntactically; but it is highly arbitrary to deny ferit in 1.115 (cit. above) independent status, as it would likewise be at 1.717 ‘reginam petit; haec oculis, haec pectore toto’.Pace Thraede (p. 22), the search for a rule, or at least a rational principle grounded on linguistic phenomena, is not misconceived.

3 Thraede is in fact deplorably imprecise over the prosody of both types of word, making no allowance for syllabification within the verse-structure (cf. p. 12). Thus all the three monosyllables in Aen. 1.81–3 that he classifies (p. 14) as ‘ωl(l)’ are in the verse ‘ωl(2)’.

4 Thraede's reference to Ott, Metrische Analysen zu Ovid Metamorphosen Buch I, p.45, is singularly unhelpful if one wants to run the alleged example to earth. Of the verses listed by Ott at p. 40 with ‘WG’ after the second foot, 1.461 ‘tu face nescio quos esto contentus amores’ must be the one that Thraede has in mind, but any system of metrical classification which lumps that together with Aen. 1.116 manifestly leaves something to be desired.

5 Those who ‘entgegen der Statistik [WGr11] in den Rang einer Z erheben mochten’ (p. 18) are clearly regarded as benighted. ‘Entgegen der Statistik’? Nearly 21 per cent (154/736) of the lines in Lucan 2 are of the type 2s + 3w + 4s. That seems to me neither statistically nor stylistically negligible. Even for Virgil, Aen. 1, the figure is just over 10 per cent (78/756); and it would be substantially higher if the count included lines such as 1. 318 ‘namque umeris de more habilem suspenderat arcum’, in which the 3w caesura is muffled (not suppressed) by the elision. On Ovid cf. CR 29 (1979), 224.

6 Comparison with Lucan 3.1–7 leads Thraede to the conclusion that in Virgil Kr (repeated pattern of metrical cola) has an incidence of 38 per cent, in Lucan 15 percent: that is, on the basis of these two passages, Lucan is metrically less monotonous than Virgil. Cf. below on elision.