Numerous studies have demonstrated that medical students and resident physicians find neurology to be one of the most difficult subjects within medicine. Reference Poser1–Reference Flanagan, Walsh and Tubridy5 In 1994, Jozefowicz described “neurophobia” as “a fear of the neural sciences and clinical neurology that is due to the students’ inability to apply their knowledge of basic sciences to clinical situations.” Reference Jozefowicz6 The authors reported that low interest and knowledge levels also contributed to neurophobia. Reference Kam, Tan, Tan, Lim, Koh and Tan7

Across Canada, neurology is a selective rotation within medical schools and for internal medicine (IM) and family medicine residents. Thus, they will receive limited or no dedicated neurologic clinical training during their careers. Lazarou et al. proposed a nationally standardized neurology curriculum for internal medicine residents, but this has yet to be adopted widely. Reference Lazarou, Hopyan, Panisko and Tai8 There is still no consensus on a standardized national neurology curriculum for internal medical residents.

Because neurology is a selective rotation for IM residents, we need a curriculum that can augment the rotation for those who opt-in but that can also provide the necessary tools for those who do not. Thus, the pedagogical approach needs to be maximized. Flipped classroom (FC) is a more active learning approach where the learner reviews content at home in a self-directed manner and then discusses it with fellow students in the presence of a facilitator. Reference Prober and Heath9 While this method has been utilized at the level of undergraduate medical education, Reference Street, Gilliland, McNeil and Royal10 it has a mixed reception at the postgraduate level. Issues include lack of buy-in from residents and faculty; residents may not engage with the content beforehand, and staff can find it taxing to prepare online materials for blended learning. Reference Sandrone, Berthaud and Carlson11 While FC curricula are successful in increasing knowledge acquisition and retention, 24% of residents in one study perceived that there was not enough protected time on inpatient rotations to implement this approach. Reference Graham, Cohen, Reynolds and Huang12 While residents “enjoy the curricular material,” they have “significant concerns about the time and motivation” required to do the pre-work. Reference Blair, Caton and Hamnvik13

Due to these perceived hurdles with FC, the aim of our study was to conduct a needs assessment to gauge the level of preparedness when residents start their neurology rotations and gain further insight into barriers, methods of teaching, and factors that would increase buy-in for a flipped class neurology curriculum for IM residents. We conducted surveys (with 5-point Likert scales) and interviews at the University of Alberta with second-year IM residents in addition to focus groups with neurology residents/staff members. We were able to conduct rotation entry and post-call surveys which are novel for a curricular needs assessment. Surveys explored aspects such as previous neurology exposure, comfort with neurological physical examination/subject matter, preferred method of instruction, and preparedness for their clinical rotation/first night on call. Data were collected via:

-

1. One-on-one IM resident interviews (N = 12)

-

2. Focus groups with neurology residents (N = 7)

-

3. Focus group of neurology staff (N = 7)

-

4. IM resident entry (N = 14) and post-call surveys (N = 9)

We followed the six-step process for thematic analysis as outlined by Kiger and Varpio to analyze interview transcripts, focus group transcripts, and survey comments. Reference Kiger and Varpio14 Qualitative data analysis involved generating themes organized within Kern’s six-step framework for curriculum development (Table 1). Reference Kern, Thomas and Hughes15 Quantitative analysis of the survey data was completed with SPSS software. We used one-sample t-tests to compare Likert means to the neutral score of 3.0 and paired t-tests to analyze differences in means between the questions. Two-sided p-values of less than .05 were considered significant.

Table 1: “Kern step and representative quotes”

Step 1: Problem Identification

Theme: Discomfort and Perception of Under-Preparedness amongst IM Trainees

Participants’ endorsed minimal clinical neurology exposure and clinical skills teaching prior to the onset of their rotation. Given that the neurology block is covered during junior years in medical school, there was a significant time gap between the classroom teaching and their clinical rotations. Residents cited that their lack of exposure contributed to the feeling of being out of their depth with the subject matter.

Step 2: Targeted and General Needs Assessment

Step 2 of Kern’s framework involves a needs assessment to determine learner-identified gaps. Just like any other system or product, it is essential that curricula are evaluated by all the involved stakeholders. Our study aimed to assess the needs of the learners (IM residents) vs. perceptions of the teachers (neurology senior residents and staff) vs. demands of board exams/clinical practice. Thus, we were able to augment what learners had to say with external sources.

Learner-Centric

Many of the topics that were brought up by the residents were in relation to preparedness for night calls. Thus, they would have liked more teaching around conditions with higher acuity such as seizures, strokes, and loss of consciousness. In addition, most residents put emphasis on greater teaching for localization of the condition, that is, brain (cortical/subcortical/brainstem) vs. spinal cord vs. peripheral nervous system and observation of their physical examination while on service.

Teacher-Derived

From the neurology residents/staff, it was evident that they wanted to focus on bread-and-butter neurology topics which would be encountered frequently by internal medicine residents. This included placing emphasis on localization, physical examination teaching, and neurologic emergencies. They stated that exposure to rare neuromuscular or other subspecialty presentations should not be the focus of the academic half day or neurology rotation.

External

A common theme from the IM residents’ comments centered on preparation for their licensing examinations. Many residents brought up topics which they felt were high yield for the Royal College.

Step 3: Goal and Objectives

Theme: Preparedness

While developing this curriculum, the aim was for it to result in residents feeling prepared for clinical service and board examinations. The data demonstrated that the ideal curriculum would result in preparedness for:

-

a. clinical duties

-

b. call/emergencies and localization

-

c. Royal College examination

Step 4: Delivery

Theme: Classroom Setting vs. On-Demand vs. Bedside

While some residents preferred a blend of didactic lectures and bedside teaching, others noted it would be useful to have video clips they could watch prior to their rotation or classroom session. One commonality, however, between the IM residents and neurology colleagues was the importance placed on bedside/case-based teaching.

Step 5: Implementation

Theme: Setting Where Curriculum Should Be Implemented

A significant component of the study focused on the tension between the likely benefits of the rotation given that not all learners do it and the lack of heterogeneity between rotation experiences from one individual to the next. It was important to understand whether curriculum was best delivered at academic half-day (AHD) or the neurology rotation itself.

Rotation

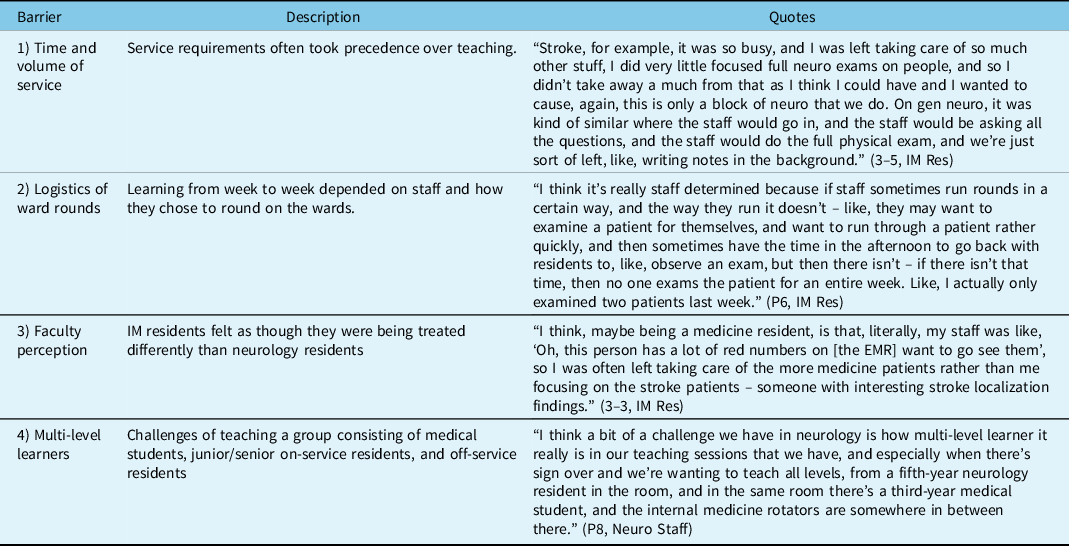

Residents noted that the benefits of learning while on rotation included reading around cases and exposure to a variety of cases. However, numerous barriers were identified (Table 2).

Table 2: Barriers to learning and teaching

Independent of the Rotation

Given that neurology is a selective rotation, and that not all IM residents will rotate through neurology, the curriculum will have to be delivered at AHD in addition to the neurology rotation in a blended format.

Step 6: Evaluation of Curriculum

Currently, there is no system in place to evaluate any perceived or actual improvement in neurological competence amongst IM residents (through AHD or on rotation), but our study provides some baseline data.

For the statistical comparison to the neutral Likert score of 3 for the entry survey, residents did not endorse comfort with the neurological physical examination (3.14, p = 0.435, Table 3) prior to their first call shift but did feel the neurology was a useful rotation for GIM residents (4.14, p < .05, Table 3). Results from the entry and post-call surveys demonstrate that there is discomfort with managing neurologic emergencies, localization, and generating a differential for neurologic diagnoses. In terms of learning style, prior to IM half-day, Table 3 illustrates that most residents would prefer watching a video (3.86, p < .05) or reviewing a PowerPoint (3.71, p < .05) in preparation for their rotation as compared to a journal article or textbook.

Table 3: Entry survey for internal medicine residents

Our results reiterate that internal medicine residents view neurology as a challenging subspecialty and that IM trainees are uncomfortable with neurological subject matter. Despite this, there is unanimous agreement amongst IM residents that neurology is a useful rotation. The entry survey also illustrates that trainees are not prepared for their neurology rotation. Interestingly, the post-call survey shows that the residents still felt uncomfortable on their first night of call (Table 4).

Table 4: Post-call table

In terms of strengths, the utilization of multiple methods and entry/post-call surveys to understand the deficits of the current neurology curriculum is a novel approach. We were able to acknowledge various intrinsic and extrinsic motivations of residents with regard to their education.

Previous research has demonstrated that neuroanatomy, limited teaching, complex diagnoses, and not enough teaching contribute to neurophobia. Reference Zinchuk, Flanagan, Tubridy, Miller and McCullough2 Our participants echoed these sentiments, acknowledging gaps in these areas.

Implementation of FC at the graduate level is still a relatively novel concept with ongoing studies examining utility and satisfaction among faculty members and learners. Graham et al. reported that 30% of IM residents found that barriers to completing pre-work included trouble accessing prework, lack of motivation, or interference of administrative clinical work. Reference Graham, Cohen, Reynolds and Huang12 Blair et al. also found that there were significant concerns in balancing pre-work with clinical duties. Reference Blair, Caton and Hamnvik13 Our participants agreed that time constraint is the limiting factor for blended curricula.

In terms of limitations, it is important to note that we have a limited sample size centered at a single institution. One of the issues is the lack of respondents for the post-call survey (<10). However, given that the year cohort has around 30 residents, this is a 30% response rate. We opted not to contact third-year residents as it had already been a year since their neurology rotation and the first-year residents had not yet rotated through neurology. There was also attrition when it came to entry surveys vs. post-call surveys, and fewer respondents were available post-call to fill out the questionnaires. Future studies could use multiple institutions to increase sample size and generalizability.

In conclusion, residents note flipped classroom could be a potential alternative to traditional didactic teaching at the postgraduate level, but highlight numerous barriers in the clinical setting. Buy-in from residents is dependent on short and concise modules with emphasis placed on bedside teaching. Staff will need to receive training in creating curricula which can be delivered in a blended format and also receive protected time to develop such modules. However, our study emphasized the major benefits associated with this pedagogical approach are utilization of “in-person” time on honing clinical acumen and refining of physical examinations skills staples of the practice of neurology.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of SSHRC through the CGS-M grant. We would also like to express our gratitude to Dr. Derrick Blackmore who provided assistance with the statistical analysis of our results.

Funding

Dr Zoya Zaeem was funded through the SSHRC CGS-M grant.

Disclosures

There are no conflicts of interest.

Statement of Authorship

Dr ZZ: Data gathering and write-up. Dr PS: Supervisor, editing of paper. Dr SK: Supervisor, editing of paper. Dr VD: Supervisor, editing of paper.