Populism is on the rise and the feeling that politicians do not listen to citizens is widely shared (see Rooduijn Reference Rooduijn2019). As a response to these widespread feelings, politicians often resort to organizing referendums (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2013; Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2007; Marien and Kern Reference Marien and Kern2018; Scarrow Reference Scarrow2001). However, little is known about the impact of these referendums on the citizens whose desires it wishes to meet, especially those with higher degrees of populist attitudes.Footnote 1 A limited number of studies has examined the relationship between citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes and preference for decision-making via referendums. These studies suggest that citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes (for ease of formulation, henceforth, ‘populist citizens’)Footnote 2 are especially supportive of decision-making via referendums (Bjånesøy and Ivarsflaten Reference Bjånesøy, Ivarsflaten, Peters and Tatham2016; Jacobs, Akkerman, and Zaslove Reference Jacobs, Akkerman and Zaslove2018; Mohrenberg, Huber, and Freyburg Reference Mohrenberg, Huber and Freyburg2019).

But does this mean that they consider the outcomes of these referendums as more legitimate? So far, no study has examined this empirically. This matters because it seems that when populist parties lose a referendum, they do not ‘take “no” for an answer’ (Verdugo Reference Verdugo2017; see also Pállinger Reference Pállinger2018; Silva Reference Silva2020). Furthermore, recent research on process preferences has found that, in general, citizens' support for referendums is often driven by instrumental considerations (Landwehr and Harms Reference Landwehr and Harms2019; Werner Reference Werner2019). Is it possible that the demand for referendums among citizens with populist attitudes is primarily an expression of the hope that referendums can function as a shortcut to materialize their own policy preferences? If they do indeed also not ‘take “no” for an answer’, holding referendums could backfire and undermine the legitimacy of the political system even further.

Using the case of a real-life referendum, we study whether populist citizens' attitudes and reactions towards decision-making through referendums are more or less driven by instrumental concerns than those of their non-populist counterparts. We find that, counter to our expectations, populist citizens turn out to be less instrumental and more principled in both their preference for and reactions to a referendum.

Populist Attitudes and Referendums

We understand populism as a set of ideas that: (1) are people-centred; (2) understand society as a conflict between the people and the elite; and (2) take on a Manichean perspective, where the people are considered as pure and good, whereas the elites are evil and corrupted (Akkerman, Mudde, and Zaslove Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014; Geurkink et al. Reference Geurkink2020; Mudde Reference Mudde2004). Based on the aforementioned definition, it is possible that citizens with a higher degree of populist attitudes consider referendums a more legitimate way of making decisions, preferring referendums out of normative considerations. Indeed, part of the populist ideology is the belief that citizens should be their own rulers and political elites only stand in the way of ‘government by the people’. Especially in a consensus democracy, the referendum can add an element of a more majoritarian type of democracy, which better fits the populist set of ideas. Populist citizens may thus hold different values regarding the structure and legitimacy of democratic decision-making (Mohrenberg, Huber, and Freyburg Reference Mohrenberg, Huber and Freyburg2019).

While there is a large literature on citizens' process preferences (for example, Bengtsson and Mattila, Reference Bengtsson and Mattila2009; Webb, Reference Webb2013), there are only few empirical studies that assess the relationship between populist attitudes and support for referendums. Those studies that tested the relationship directly found a positive relationship between populist attitudes and support for referendums (Bjånesøy and Ivarsflaten Reference Bjånesøy, Ivarsflaten, Peters and Tatham2016; Jacobs, Akkerman, and Zaslove Reference Jacobs, Akkerman and Zaslove2018; Mohrenberg, Huber, and Freyburg Reference Mohrenberg, Huber and Freyburg2019).

Based on these previous findings, we formulate a first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The higher the degree of populist attitudes of a citizen, the more they support the referendum in question prior to the vote.

Yet, even if we find such a positive relationship between populist attitudes and referendum support, this need not necessarily mean that support for referendums is based on normative considerations about how democratic decisions ought to be made. In fact, a second, explanation could be that populist citizens favour referendums based on instrumental considerations. Recent studies on process preferences have found that such instrumental considerations generally play an important role in shaping citizens' support for referendums (Landwehr and Harms Reference Landwehr and Harms2019; Werner Reference Werner2019), as well as more general attitudes towards electoral reform (Biggers Reference Biggers2019; Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Reference Bowler, Donovan and Karp2006).

While there may be a good theoretical ‘fit’ between populism and referendums, an alternative expectation is that the subgroup of populist citizens relies on instrumental considerations to support and evaluate referendums, even more so than non-populist citizens. Non-populist citizens may believe that there are other routes to achieve desired policies (for example, expert government or simply via contacting politicians or other types of traditional political participation). For them, referendums are just one tool. For populists, referendums are likely to be seen as the single most effective tool, as they bypass the elites by handing over power to the people (see Mohrenberg, Huber, and Freyburg Reference Mohrenberg, Huber and Freyburg2019: 4).Footnote 3 Perceived legitimacy is, then, derived not from the process as such, but from the favourability of the outcome. Hence, we expect the relationship between instrumental considerations and support for a referendum to be even stronger among populist citizens.

General studies on process preferences have found that instrumental considerations typically come in two forms (Werner Reference Werner2019). First, citizens may support a referendum on a given question more so when they are in favour of the policy proposal under discussion. This is because citizens have nothing to lose and much to gain from a referendum on a proposal (or veto of an existing bill) that they endorse. Second, citizens may be more supportive of a referendum if they expect to win the referendum (see also Landwehr and Harms Reference Landwehr and Harms2019). In both cases, citizens support a referendum because they believe it benefits them. Based on the aforementioned reasoning highlighting that populists consider referendums the single most effective tool to achieve desired policy outcomes, we thus formulate the following two moderator hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a: The higher the degree of populist attitudes, the stronger the relationship between support for the specific policy proposal and support for a referendum on that topic.

Hypothesis 2b: The higher the degree of populist attitudes, the stronger the relationship between majority perceptions about an issue and support for a referendum on that topic.

If citizens with populist attitudes are not genuinely in favour of referendums, but rather consider them a convenient tool to reach desired policies, this also has consequences for how legitimate they judge the outcome of a referendum. Therefore, the reaction of citizens with populist attitudes that lose referendums is of particular importance to this analysis. Extensive work both on elections and on procedural fairness has shown that outcome favourability plays an important role in shaping citizens' evaluations of the decision-making process and their likelihood to accept the decision (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson2005; Arnesen Reference Arnesen2017; Esaiasson et al. Reference Esaiasson2019; Marien and Kern Reference Marien and Kern2018; Merkley et al. Reference Merkley2019). If populist citizens root their support for referendums in the expectation of favourable outcomes, losing a referendum could lower their willingness to accept the decision (that is, they are ‘sore losers’)Footnote 4:

Hypothesis 3: The higher the degree of populist attitudes, the lower the willingness to accept the outcomes of referendums among decision losers.Footnote 5

Methodology

Case

We test these hypotheses on a real referendum, namely, the 2018 Dutch referendum on the Intelligence and Security Services Act 2017. Studying a real referendum has the obvious advantage of improving ecological validity compared to hypothetical surveys or experiments. The downside of our design is that we can only test correlational relationships. Thus, we cannot make causal claims. Further, we have to be cautious in generalizing from this case. To this end, we provide more detailed information on the case in the Online Appendix. What makes this referendum ideally suited to studying the relationships in question is that the policy preference does not overlap substantially with populist attitudes, which can make it difficult to disentangle the role of populist attitudes and loss in the referendum. As Fig. A1 in the Online Appendix shows, we have sufficient variation of populist attitudes among both proponents and opponents of the referendum proposal.

Dataset

The data were collected by the Longitudinal Internet studies for the Social Sciences (also known as the LISS-panel), a high-quality probability sample survey panel run by CenterData (University of Tilburg). We use data from two waves of the referendum study. Data for the pre-wave were collected in the weeks prior to the referendum (5–20 March; response = 74.2 per cent). Data for the post-wave were collected after the referendum (22 March–8 April; response = 78.7 per cent). The sample of the post-wave consists partly of respondents who were also invited to the previous waves and partly of ‘fresh’ respondents. For the main analyses, we construct an analytical sample including respondents who answered the questionnaire both pre- and post-wave. This yields an analytical sample of 666 respondents. We also conduct a robustness check on our post-wave analysis including the full sample (see Table A6 in the Online Appendix; N = 1,322). The turnout was overestimated in the dataset – a classic problem for survey research about voter turnout. The vote choice distribution is slightly skewed towards decision losers in our analytical sample, yet not in the full post-sample, with which we find substantially the same results (see Table A6 in the Online Appendix). In terms of demographics, our sample compares well to Dutch census data, yet is slightly skewed towards men, older people and higher-educated citizens (Statistics Netherlands 2018). Descriptive information about the sample can be found in Tables A1 and A2 in the Online Appendix.

Operationalization

We use two dependent variables. First, we measure support for the referendum on the information law (seven-point scale, measured in the pre-wave and used for H1, H2a and H2b). Second, we measure to what extent citizens were willing to accept the result of the referendum (seven-point scale, measured in the post-wave and used for H3).

Our main independent variable is populist attitudes. We use the widely used, standard, six-item battery of populist attitudes devised by Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove (Reference Akkerman, Mudde and Zaslove2014), measured in the post-wave. It should be noted that one of the items in the scale asks whether citizens should decide instead of politicians on the most important issues. There may be conceptual similarity between this item and support for the specific referendum under study, which is one of our dependent variables. Hence, to err on the side of caution, we decided to drop this item from our main analysis. Robustness checks using the full scale reveal substantially the same results (see Tables A7 and A8 in the Online Appendix).

Further, we measure citizens' policy preferences regarding the information law under question (binary, pre-wave) and their expectation of the referendum result, which is then matched to their policy preference to construct a majority perceptions variable (binary, pre-wave). More information on question wording can be found in the Online Appendix.

Results

In the following, we test the outlined hypotheses. It should be noted that we control for party preferences in all models, yet do not show them in the main graphs for ease of readability. The complete regression tables can be found in the Online Appendix (see Tables A4 and A5).

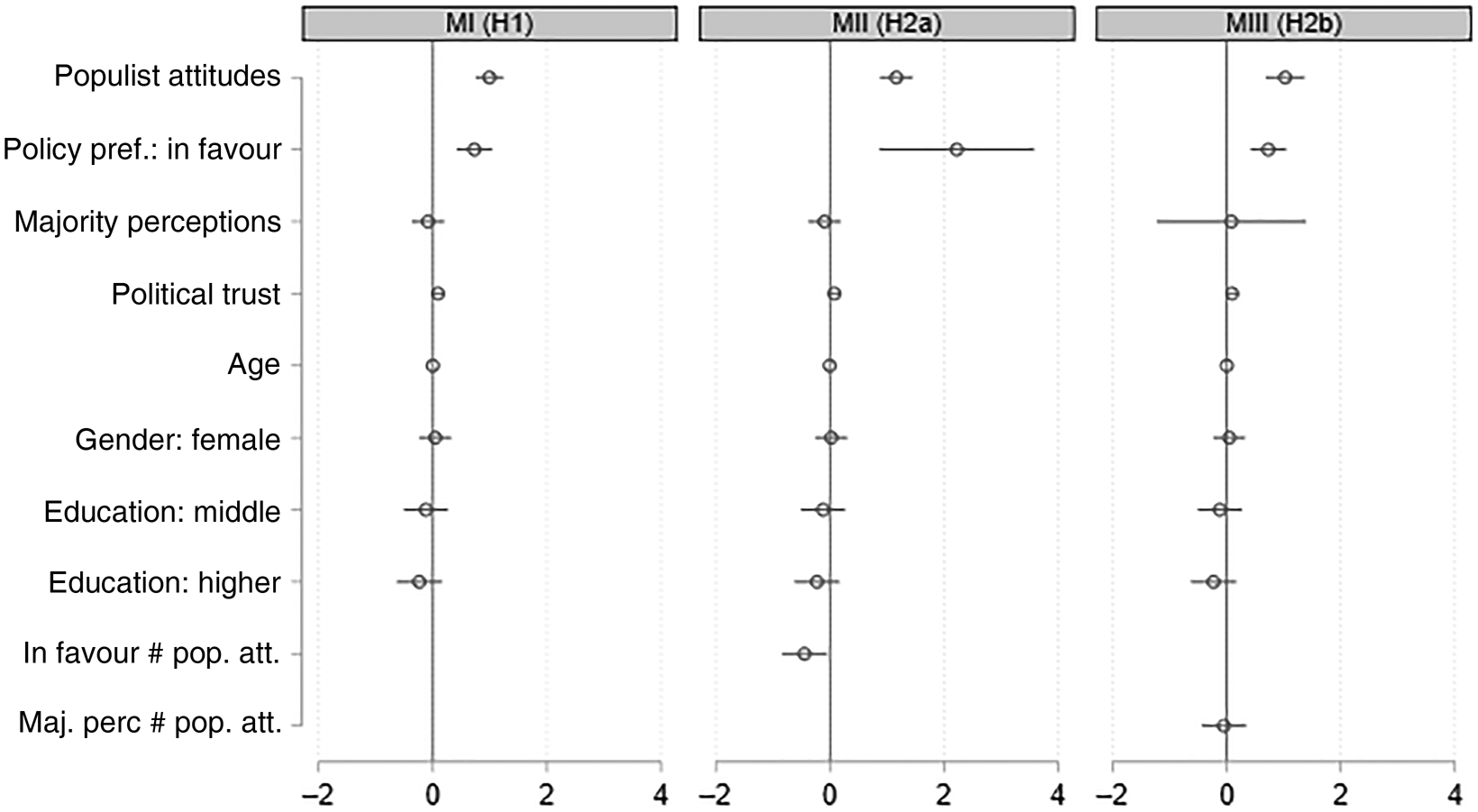

H1 predicted that citizens with high levels of populist attitudes would be more supportive of the referendum on the information law than citizens with low levels of populist attitudes. As can be seen in Fig. 1 (Model I), this is indeed the case. Populist attitudes are positively and significantly related to support for the referendum on the information law.

Figure 1. Regression of support for referendum (pre-wave).

Note: Estimates are unstandardized regression coefficients. N = 666. R2 MI = 0.23; R2 MII = 0.23; R2 MIII = 0.23. Party preference was included in model but is removed for ease of readability. Bars represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. For the corresponding table, see Table A4 in the Online Appendix. Policy pref = Policy preference; Pop. att. = Populist attitudes; Maj. Perc. = Majority perception

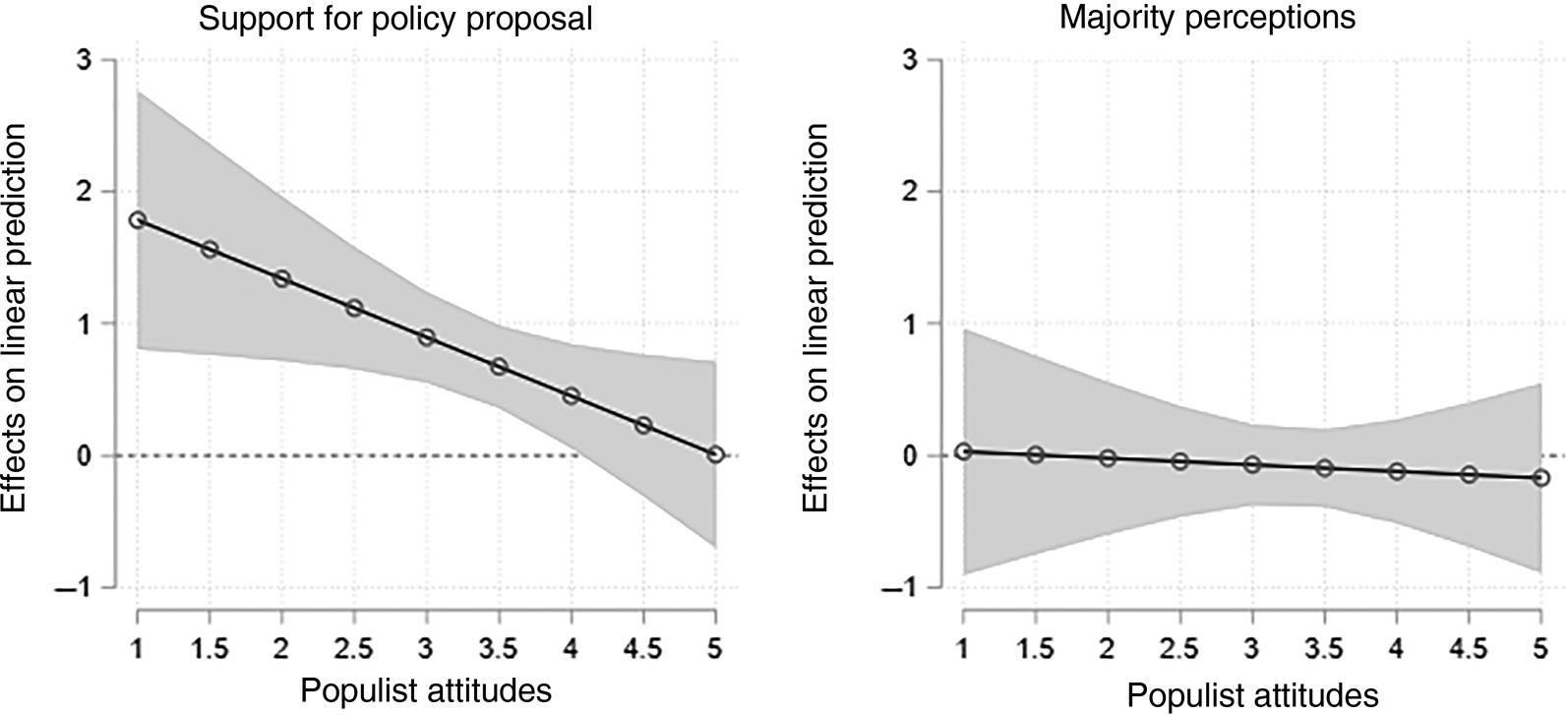

But are populists more instrumental in their support for the referendum? H2a expected that populist attitudes would interact with support for the policy proposal and with the expectation of winning the referendum, indicating that these instrumental considerations are especially prevalent among citizens with populist attitudes. We start with an investigation of the interaction with support for the policy proposal (H2a). As can be seen in Model II, there is indeed a significant interaction between populist attitudes and support for the policy proposal (p < 0.05) but in the other direction than predicted. It turns out that populist citizens' support for the referendum is less driven by instrumental concerns about changing a specific policy. This interaction is visualized in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Marginal effects of support for the policy proposal and of majority perceptions on support for the referendum across populist attitudes.

Note: N = 666. The graph presents the visualization of the interaction in Model II and Model III of Fig. 1. For the corresponding table, see Table A4 in the Online Appendix.

Turning to the interaction with the expectation of winning (H2b), we expected that populist citizens would be especially supportive of a referendum if they expect to win it. As Model III shows, this is not the case: we see no indications of an interaction between populist attitudes and majority perceptions (also visualized in Fig. 2).

Our hypotheses about populist attitudes and support for referendums have only partly been confirmed. Replicating results from existing research, we find that citizens with populist attitudes are more in favour of the referendum in question (H1). Furthermore, and contrary to our own expectations, we find that, compared to non-populist citizens, their support is either less driven by instrumental, policy-specific concerns (H2a) or at least not more so in regards to their expectation of winning (H2b).

We now turn to the post-wave to investigate how populist citizens reacted to the outcomes of the referendum. In H3, we expected that such citizens would be less likely to consider the referendum outcome legitimate if they did not get the desired policy outcome.

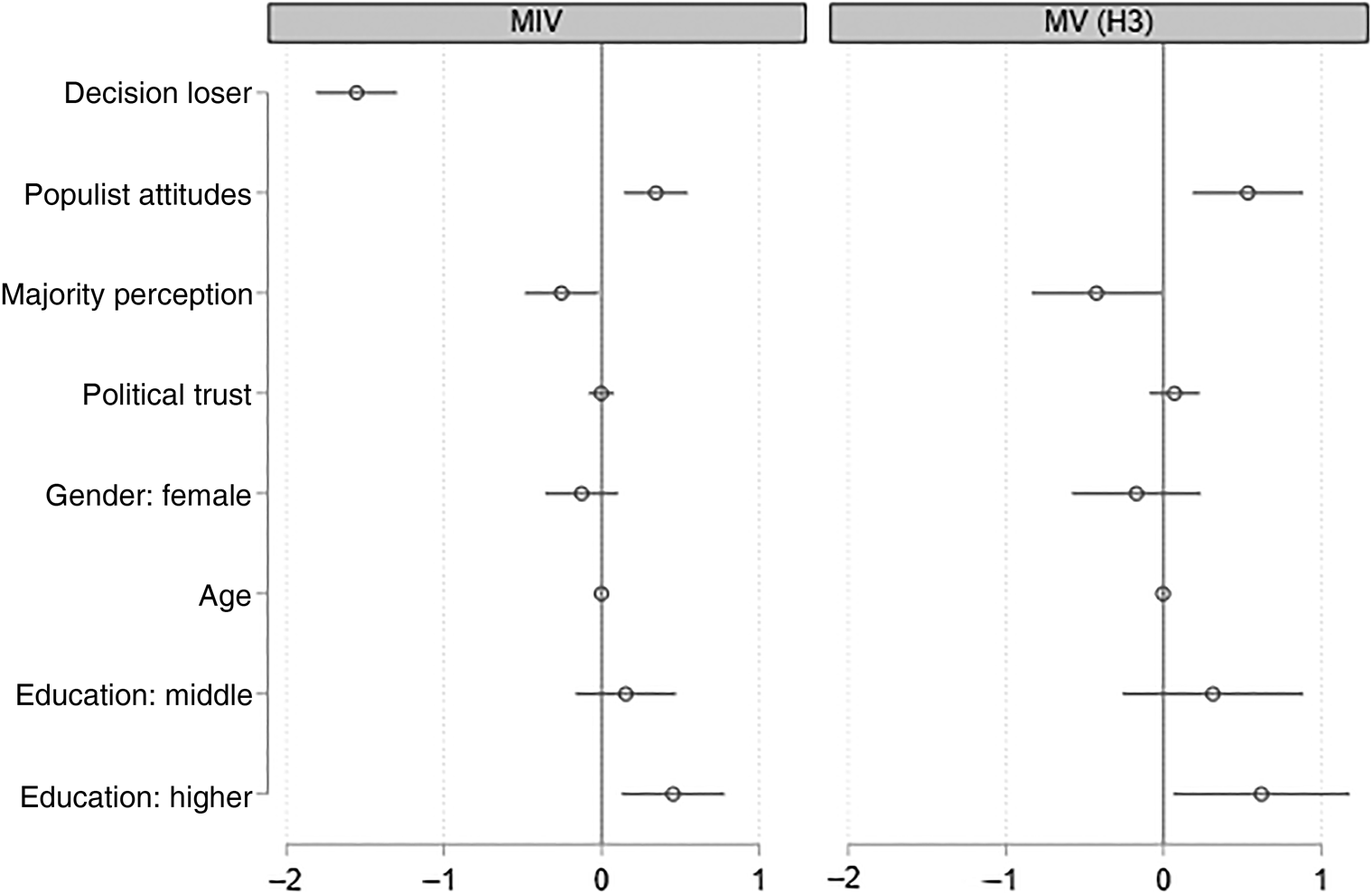

We first test how acceptance of the referendum result relates to outcome favourability and populist attitudes among the whole sample (see Model IV in Fig. 3). As expected, we see that those who lost exert lower willingness to accept the outcome of the referendum than those who won. Interestingly, populist attitudes are positively (and significantly) associated with acceptance of the outcome. However, this could be driven by decision winners (Marien and Kern Reference Marien and Kern2018).

Figure 3. Linear regression of acceptance of the referendum outcome (post-wave).

Note: Estimates are unstandardized regression coefficients. MV shows effects for the subgroup of decision losers. NMIV = 666, R2MIV = 0.29; NMV = 339, R2MV = 0.10. Party preference was included in the model but is removed for ease of readability. Bars represent 95 per cent confidence intervals. For the corresponding table, see Table A5 in the Online Appendix.

We then turn to the subsample of decision losers in Model V. We expected a negative correlation between populist attitudes and acceptance of the unfavourable referendum result. However, we find the exact opposite: the higher a citizen's degree of populist attitudes, the higher their willingness to accept the unfavourable outcome. It therefore seems that citizens with high populist attitudes are more gracious losers in a referendum than citizens with low populist attitudes, disconfirming our hypothesis.

Robustness Checks

To check the stability of our findings, we ran several robustness checks. First, we run the analyses on decision acceptance using the full sample of third-wave respondents (N = 1,322) instead of the overlap sample between the pre- and post-wave that we present in the main analysis. We find substantially the same results (see Table A6 in the Online Appendix).

Second, we rerun all our analyses using the full populist attitudes scale. This scale includes the item ‘On the most important issues, citizens should decide instead of politicians’ that we removed for our main analysis because it related too closely to support for populist attitudes. We find substantially the same results as in our main analysis, with slightly bigger effect sizes. The results can be found in Tables A7 and A8 in the Online Appendix.

Third, we assess the conditionality of our findings on the policy issue of the referendum to gain insights into its generalizability. While there was substantial attention to the topic of data protection in the public debate, it is not the most salient and pressing policy issue for most citizens. We interact the importance that respondents attributed to the policy issues with populist attitudes in our analysis of decision acceptance for both the full sample and the decision losers. We find no significant interaction effect; hence, even populist citizens that cared strongly about the issue were more willing to accept an unfavourable outcome than their non-populist, caring counterparts. The results can be found in Table A9 in the Online Appendix.

Conclusion

We expected populist citizens to be sore losers when compared to non-populist ones. It turns out that this is not the case in our study. Citizens with populist attitudes were less instrumental and more principled in their support for referendums, and in line with this, they were more accepting of the referendum result, even when the outcome was unfavourable. The obtained results are robust across different analysis specifications.

These findings have a range of implications. First, they shed light on the potential of referendums to strengthen popular legitimacy. The concern about growing dissatisfaction with the political system and resulting low levels of legitimacy is prevalent both in political science and among practitioners. Many critics worry that participatory processes will only appeal to those citizens who are already politically privileged – the interested, trusting and educated citizens – and will cause even more frustration among those who feel excluded and neglected (Smith Reference Smith2009). Our results suggest that referendums hold a normative appeal to citizens with populist attitudes and could build consent even in the light of unfavourable policy outcomes. It seems that populist citizens are not necessarily up for ignoring the rules of the game; they just think there should be different rules.

However, a second implication opens up a problem for political practice. What should be done if different subgroups of the population consider different decision-making arrangements as legitimate? For instance, it could be that citizens are dissatisfied but, at the same time, consider their fellow citizens incompetent. Such citizens are likely to prefer expert democracy and dislike referendums. This causes a conflict between the normative democratic preferences of different societal groups, one that is not easily resolved and requires the consideration of other democratic goods.

As with every study, ours comes with some limitations. First of all, we could only study correlations between our variables of interest and can therefore only theorize about the causal relationships. Second, since we use data from a single referendum, questions of generalizability may arise. While the Dutch 2018 referendum is an excellent first testing ground to examine the relationship between populist attitudes and losing referendums, as populist citizens were relatively evenly distributed in terms of winning and losing, it is important to test the findings in other country settings as well. Although our study indicates that populist citizens' support for referendums is more normative and, consequently, can correlate positively with decision acceptance, it remains to be examined under which circumstances such correlations materialize. Third, it remains to be seen whether populist citizens would behave similarly for highly contested issues, such as migration. While our data suggest that issue importance does not change populist citizens' willingness to accept the decision, future studies are required. Evidently, while a crucial one, our research constitutes only a first step. Indeed, it remains to be investigated further under which specific circumstances and to what extent referendums can help bring populist citizens back in.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000314.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used for the analyses in this manuscript is publicly available and can be found at: https://www.dataarchive.lissdata.nl/study_units/view/815. Replication code (see Werner and Jacobs Reference Werner and Jacobs2021) can be found at the Harvard Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DTN3JF.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wouter van der Brug, André Bächtiger and Saskia Ruth-Lovell, as well as the three anonymous reviewers, for helpful comments on this article.

Funding

Part of this research was financed via Dutch National Science Fund (NWO) as part of the NWO-VIDI project no. 195.085. This project has also received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No. 759736).