Article contents

II. Inscriptions1

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 November 2011

Abstract

- Type

- Roman Britain in 2002

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © R.S.O. Tomlin, M.W.C. Hassall and A. Monumental 2003. Exclusive Licence to Publish: The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies

References

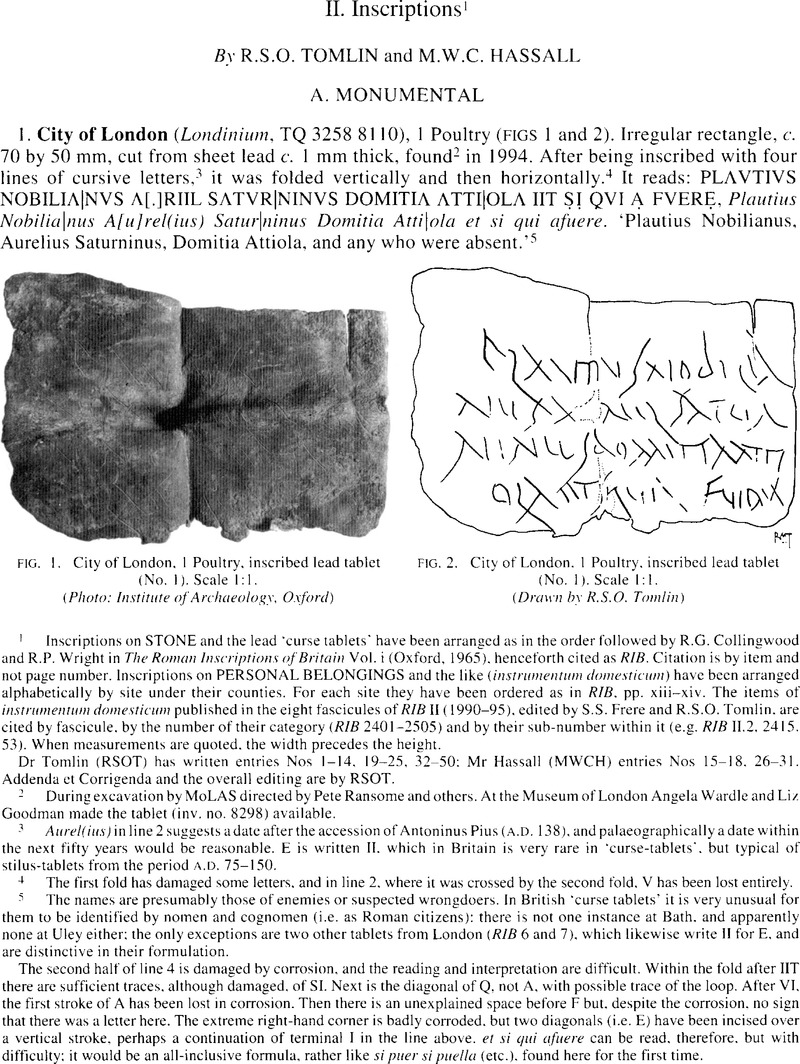

2 During excavation by MoLAS directed by Pete Ransome and others. At the Museum of London Angela Wardle and Liz Goodman made the tablet (inv. no. 8298) available.

3 Aurel(ius)in line 2 suggests adate after the accession of Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138), and palaeographically a date within the next fifty years would be reasonable. E is written II. which in Britain is very rare in ‘curse-tablets’, but typical of stilus-tablets from the period A.D. 75–150.

4 The first fold has damaged some letters, and in line 2. where it was crossed by the second fold. V has been lost entirely.

5 The names are presumably those of enemies or suspected wrongdoers. In British ‘curse tablets’ it is very unusual for them to be identified by nomen and cognomen (i.e. as Roman citizens): there is not one instance at Bath, and apparently none at Uley either; the only exceptions are two other tablets from London (RIB 6 and 7). which likewise write II for E. and are distinctive in their formulation.

The second half of line 4 is damaged by corrosion, and the reading and interpretation are difficult. Within the fold after IIT there are sufficient traces, although damaged, of SI. Next is the diagonal of Q, not A. with possible trace of the loop. After VI. the first stroke of A has been lost in corrosion. Then there is an unexplained space before F but. despite the corrosion, no sign that there was a letter here. The extreme right-hand corner is badly corroded, but two diagonals (i.e. E) have been incised over a vertical stroke, perhaps a continuation of terminal I in the line above, et si qui afuere can be read, therefore, but with difficulty: it would be an all-inclusive formula, rather like si puer si puella (etc.). found here for the first time.

6 With the next two items during excavation by MoLAS directed by Nick Bateman for the Corporation of London, GYE 92 <1069>, <5037> and <1070> respectively. At the Museum of London Angela Wardle made them available.

7 FIG. 3 represents it as if more or less flat, so as to show all the surviving text. The hole has almost certainly destroyed parts of lines 6 and 7, and so is subsequent to the text. There is no sign that it developed because of corrosion round a nail, but this is a possibility.

8 Line by line commentary, citing R.S.O. Tomlin, Tabelláé Sulis: Roman Inscribed Tablets of Tin and Lead from the Sacred Spring at Bath ( 1988), and R.S.O. Tomlin. ‘The inscribed lead tablets’, in A. Woodward and P. Leach, The Ulex Shrines (1993). 113–30.

1. [d]eae Dea[na]e. ‘Diana’ is the earlier form and remains standard, but the variant ‘Deana’ is quite common in the imperial period (for examples see Dessau, ILS III, p. 524). and this is the first from Britain. It seems to be the first ‘curse tablet’ addressed to the goddess, certainly the first from Britain, where it is also the first written evidence of her cult from London; significantly it was found near Goldsmiths' Hall, itself the find-spot of an altar to Diana and associated(?) masonry in 1830 (RCHM Roman London (1928), 43, 120 and pi. 12). Diana also appeared with other deities on a major London monument: see Hill, C., Millett, M., Blagg, T., The Roman Riverside Wall and Monumental Arch in London (LAMAS Special Papers 3, 1980), 162–4, No. 32.Google Scholar

2–3, capitularem etfas[c]iam. Both items have already occurred in British ‘curse tablets': capitularem at Bath (Tab. Sulis 55, with note), fascia and cap(t)olare(?) at Caistor St Edmund (Britannia 13 (1982), 408, No. 9), fascia and capit(u)larem at Uley (with other clothing, in an unpublished tablet cited as Uley Shrines, 129, No. 62). That they occur together suggests they were related but not identical garments, perhaps a head-covering (i.e. hat or hood) and neck-band (i.e. scarf), rather than the ‘head(band)’ suggested by the gloss cited in Tab Sulis 55. According to Isidore (Orig. 19. 31. 3), capitulare was a ‘vulgar’ word for capitulum or cappa, and TLL cites it in the neuter; but in Britain at least, the masculine form was usual.

3–4, minus parta tertia. A god's interest is often engaged by the ‘gift’ of a fraction of the stolen property, but two-thirds is unusually high. Compare Uley Shrines, 121, No. 2, deo s(upra)dicto tertiam partem [djonat … tertia pars donatur (one-third), with note there of other examples.

4, si quis hocfeci[t]. The scribe slipped into cursive for the letters QVI S. The clause is formulaic (compare Tab. Sulis 44.5, with note), a variant of the more common qui hoc involavit (etc.); what has been ‘done’ is usually explicit, but here it must be inferred.

5–6. These formulas are so common (see Tab. Sulis, pp. 67–8) that the first can be safely read in 5; in 6, although the distinctive diagonal of R makes the restoration of [s]er[vus] likely, the rest of the line is difficult because so little survives.

7, don[o eum] is a reasonable conjecture (for the formula see Tab. Sulis, pp. 63–4) since, although it is the stolen property which is ‘given’ in 1–3, attention has turned to the thief (si quis hoc feci[t]) who must be the subject of possit.

7–8, nee p[er] / me [vi]v[ere] possit. Interdiction of the thief s natural functions is frequent (see Tab. Sulis, pp. 65–6), but none of the known formulas will fit here. So this restoration is conjectural, but accords with the surviving letters and their spacing.

9 This would suggest it was a ‘curse tablet’, like RIB 6 and 7 (London) which were also nailed.

10 The dotted letters are especially uncertain and ambiguous. In (a), the slight diagonal stroke between VIN and MO is complete, and not part of a letter. The third letter of line 2 most resembles a clumsy cursive B, but D and L (cut twice) are possible readings. The text of (b) is even less distinct. To the left at an angle are two earlier lines of sinuous cuts, the first of which might be S in line 1. In line 2. the second letter would be a ‘capital’ R if the curved trace above it were deliberate, but otherwise a late cursive form, a dating not borne out by the rest of the lettering. Overall, no interpretation is possible; perhaps two non-Roman personal names with patronymics.

11 During excavation by Pre-Construct Archaeology in advance of development by Berkeley Homes (see above, p. 345). Jenny Hall made it available to RSOT while it was being conserved at the Museum of London. It is now in the Cuming Museum, but its ultimate location is uncertain.

12 A line-by-line commentary follows. See Corcoran, further S., Salway, B., Salway, P.. ‘Moritix Londiniensium: a recent epigraphic find in London’, British Epigraphy Society Newsletter, n.s. 8 (autumn 2002), 10–12Google Scholar ; Current Archaeology 182 (Nov. 2002), 48; Museum of London, Archaeology Matters 19 (March 2003); J.N. Adams. ‘The word moritix in a new inscription from London’, ZPE forthcoming. For the etymology of moritix we are grateful to Prof. Patrick Sims-Williams.

1. NVM AVGG. This dedication is often combined with one to a deity, a plurality of Emperors being commonly indicated by AVG or AVGVSTORVM; but for AVGG see RIB 459, 918, 1596, 2042, and especially 627. NVM AVGG (dated A.D. 208). While AVGG might refer to Emperors living and dead, it is best taken to refer to two living Emperors; see further Fishwick, D., ‘Numinibus Aug(ustorum)’, Britannia 25 (1994). 127–41.CrossRefGoogle Scholar This usage is first found for Marcus Aurelius and his colleagues (A.D. 161–9 and 177–80), a date much better suited to the quality of the lettering than the Severan period.

2–3. The god Mars Camulus is attested in Britain only by RIB 2166 (Bar Hill), and is otherwise connected with the Remi: see for example AE 1935, 64 (his temple at Reims), CIL xiii. 8701 =AE 1980, 656 (another temple erected by cives Remi). and CIL vi. 46 (Rome, a dedication by a civis Remus).

3–5. The dedicator is otherwise unknown, but his rare nomen is ‘manufactured’ from a cognomen (Tiberinus), like many in northern Gaul. The Bellovaci were a civitas somewhat to the west of the Remi, and the expansion of c(ivis) Bell(ovacus) is inevitable; compare CIL xiii. 611 (Bordeaux), ob memoriam Vestirli Onatedonis (filii) c(ivis) Bel(lovaci).

6. MORITIX. As moritex this term is found in CIL xiii. 8164a = ILS 7522 (Cologne), a dedication by G(aius) Aurelius G(ai) l(ibertus) Vents negotiator Britannicianus moritex. It should probably also be read in RIB 678 (York), the lost sarcophagus of M(arcus) Verec(undius) Diogenes sevir col(oniae) Ebor(acensis) itemq(ue)(?) morit(ix) cives Biturix Cubus. The etymology of the word (‘seafarer’) from Celtic *mori-teg-/tig- is not in doubt, and either spelling would be acceptable; see Uhlich, J., ‘Verbal governing compounds (synthetics) in early Irish and other Celtic languages’. Transactions of the Philological Society 100 (2002), 403–33.CrossRefGoogle Scholar at 420 s.v. moritex: and X. Delamarre, Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise (2003), 194. But the specific meaning is unknown. Moritex was evidently a term applied to Gauls engaged in seaborne trade between Britain and the Continent, but was it simply a loan-word equivalent to nauta (‘sailor’). navicularius (‘shipmaster’) or nauarchus (‘ship's captain’), or was the moritex specifically an official, or at least a member of a trade association (collegium)? The last seems quite likely.

7–8. LONDINIENSI/VM.|Hitherto this word has occurred only as the adjective derived from Londinium (see Rivet, A.L.F. and Smith, C., The Place-Names of Roman Britain (1979). 396)Google Scholar , and this is its first occurrence as a noun. ‘Londoners’. The informality of the usage in -enses does not mean that London lacked formal status: compare AE 1912.250 (Ostia, a colonia), the epitaph of afire-fighter who received a public funeral from the Ostienses: or CIL v. 8972 = ILS 1459 (Aquileia. also a colonia), a public dedication to their patron by the Aquileienses. This Gallic citizen evidently called himself a ‘Londoner’ in the way that Verecundius Diogenes, cives Biturix Cubus. was also a sevir Augustalis of the colonia Eboracensis at York (RIB 678, cited above).

8. After PRIMVS there is a broken edge with trace of a triangular medial point and two unidentifiable serifs. In the middle of 9 there is sufficient trace of V and A (or M). Since the surviving text ends here, the question of whether moritix stood alone, or was qualified by Londiniensium and even by primus, must remain open. Moritex is unqualified in CIL xiii 8164a and RIB 678 (see above): too small a sample to be decisive, but suggesting that Celerianus was not ‘moritix of the Londoners’ (whatever that might mean), but rather a moritix who was the first ‘Londoner’ to […]. But what his achievement was can only be guessed: perhaps he introduced a new cult, rather like Aurelius Lunaris. sevir Augustalis of the coloniae of York and Lincoln, who brought his own altar with him from Britain to Bordeaux (JRS 11 (1921), 101–7); or perhaps he was the first to hold a new office, for which compare ILS 7142, primus Illlvir m(unicipii) A(urelii) Apuli and later 1143, primus annualis mun(icipii) Sept(imii) Apul(i): also IRT 412, praefiecto) publ(ice) creato cum prim?m civitas Romana adacta est.

13 During excavation for Tyne and Wear Museums directed by Paul Bidwell. Alex Croom made it available (IM 137 55738).

14 Presumably the initials of nomen and cognomen, M(…) B(…), whether those of a mason or of his centurion.

15 By Prof. Roger Wilson, who has described it fully and discussed its significance in part II (‘A new Roman quarryman's inscription on Barcombe Hill’) of his forthcoming ‘Journeymen's jottings: two Roman inscriptions from Hadrian's Wall’, Archaeologia Aeliana 5th ser. 31 (2003). For part I (‘A lost Roman inscription from Benwell (RIB 1352) rediscovered’) see Britannia 32 (2001), 399, Addenda et Corrigenda (d).

16 CSIR 1.6, 147, No. 442.

17 Isolated numerals often occur on the face of building-stones from Hadrian's Wall, and are thought to mark quarry-batches, but there is no close parallel from the quarry-faces themselves. The question is discussed by Wilson (see above, n. 15).

18 With the next four items during excavations for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew and Robin Birley, who made them available. This altar (No. 8), which is now displayed in the museum, has been described and discussed in detail by Anthony Birley, ‘The inscription’, and Pat Birley, ‘Comments on the carving’, in Birley, R., Birley, A. and Blake, J., The 1998 Excavations at Vindolanda: the Praetorium site, interim report (Vindolanda Trust 1999), 29–38.Google Scholar See further, n. 21 below.

19 A provenance it shares with RIB 1685 (dedicated to the genius praetori by a prefect of the Conors III/Gallorum), RIB 1686 (to Jupiter and the other Immortal Gods and the genius praetori by another prefect of the same cohort) and RIB 1687 (to Jupiter and the genius and Guardian Gods of the same cohort by a dedicator or dedicators now illegible). Stylistically it is related to RIB 1686 (the 2-line erasure dates this to Alexander Severas, compare RIB 1706), and the presumption must be that the dedicator was the officer commanding the cohors llll Gallorum. But this is difficult: see below, n. 21, lines 9–10.

20 Letter heights: 1. 30–35 mm: 2. 40–45 mm: 10. 45 mm; 11, 45–50 mm.

21 Notes on the reading. Space forbids full discussion of Birley's ‘provisional reading’ (see above, n. 18) which derives from detailed examination of the original. Unfortunately the surface is so worn that any shift in illumination changes some of the ‘ghost’ letters visible in 3–10.

2–3. There is not enough room for ET before [GE]NIO: it was probably understood, but the ligatured letters might have been squeezed in. At the beginning of 3, the placing of the vertical stroke suggests T rather than E; E would seem to have been ligatured to it.

3–4. [SACRVM] has perhaps been lost here by analogy with RIB 1685, but not if the dedicator's cognomen began in 4.

4–5. The dedicator's name must have followed the dedication (compare RIB 1685 and 1686). The traces might suggest the cognomen VI/C[T]OR or more likely VI/C[T]OR[I]N[VS], widely spaced, but Birley reads VS./G…OTRIBLE. here (‘surely trib(unus) le[g(ionis)]’). This would require a (rare) cognomen ending in -O.

6–9. Almost nothing can be made of these lines, which must have contained the dedicator's rank or post, and perhaps his origin (compare RIB 1686). NC is fairly certain at the end of 7, and also perhaps M in the middle of 8 and 9. NC is suggestive of provincia (and thus the dedicator's origin), and there is indeed possible trace of O in the appropriate place; but after it the traces suggest B or S. V cannot be read or restored, so Birley reads P[R]OBINC(IAE); but the B/V confusion this would require is apparently alien to the Latin of Roman Britain.

10. ORVM. widely spaced, must be the genitive plural termination of the unit-title, but the expected COH III GALL cannot be read or restored in 9. Of this line it can be said (with Birley and Paul Holder) that the traces would allow [N]VM FRI [SI], i.e. 9–10, [n]um(eri) Fri[si]orum. but this is hypothetical: the unit is unknown and difficult to parallel.

22 In 1, DEO has been read conventionally, but the spacing favours DIO (compare Britannia 33 (2002), 355, No. 1. with note). What follows is apparently anew variant of the god's name, but five others with initial H are known already (see RIB I Index, p. 68). In 3–4. N[…]/VEGV must conceal the name of the dedicator. There is space for S at the end of 4, but no sign of it. The reading of 5 is clear, but this variant of the VSLM formula is unattested: compare RIB 1099 (Ebchester). VLS.

23 See Britannia 33 (2002). 295–7.

24 Most likely a dedication to ‘Vitiris’, whose later cult is well attested at Vindolanda. but there is a third diagonal stroke attached to V and trace of a fourth, suggesting VV[…]. Further traces are consistent with a reading VVTRI, but this is conjectural. The first letter is certainly V, not part of M, and VI[…] cannot be read. Many variant spellings of the god's name are known, including ‘Huutris’ in the previous item (No. 9), of which this might be an unaspirated form.

25 Ln line 3. there is space to restore only one letter, but the name ‘Maximus’ is inevitable, so presumably X and 1 were crammed together. The letter lost in 4 was probably S. s(olvit). but the traces in 5 do not admit the rest of the VSLM formula. They suggest F (or P) and two vertical strokes (not M). looking somewhat like F1L.

26 With RIB 2202 (for which see below. Addenda et Corrigenda (a)); see John Knox. A View of the British Empire (3rd edn. 1785). 61 1–12, footnote. Both stones were taken to Richmond (Surrey), and are now lost. We owe this reference to Prof. Lawrence Keppie.

27 Not a praenomen. since this would be abbreviated, but the well attested cognomen. It also contains a Celtic name-element, so it is found as a peregrine name with patronymic: see for example RIB 2043 + add. If the inscription was complete, it would have been a building stone inscribed with only a personal name.

28 By Ross Metcalfe, who informed the landowner and farmer, Peter Thorpe of Rhydings Farm, who has given the stone to Pontefract Museum. Peter Houlder. Chairman of Pontefract and District Archaeological Society, provided photographs and detailed information including a copy of his preliminary report to the Society. The discovery has been noticed in Farmers Weekly for 30 August 2002 and Current Archaeology 182 (November 2002), 49.

29 A.D. 276 (reigned 7 June – 9 September). Restored after RIB 2275, a cylindrical milestone of similar gritstone and the same in diameter, found in Castleford c. 5 (Roman) miles north of East Hardwick on the same Roman road (Margary 28b). This new milestone is the emperor's fourth from Britain; another seven are known from the Continent. Since he never left Asia Minor in his three-months' reign, they represent an assertion of authority rather than road-maintenance: see Sauer, E., ‘M. Annius Florianus: ein Drei-Monate-Kaiser und die ihm zu Ehren aufgestellten Steinmonumente (276 n. Chr.)’, Historia 47 (1998). 174–203.Google Scholar

30 With the next three items during excavation by Colchester Archaeological Trust for Tarmac plc and English Heritage, directed by Philip Crummy who. with Don Shimmin. provided information, drawings and photographs. Four other items carry what appear to be deliberate scratches. (1) Several sherds from the base of a terra rubra platter stamped DACOVIR: a straight line. (2) Base sherds from a terra rubra platter (Camulodunum type 7/8; A.D. 25–50). stamped ATTISSU: a ‘grid’ design. (3) Base sherds from a terra rubra platter (Camulodunum type 7/8: A.D. 25–50). stamped ATTISSU: X+V. (4) Segment of a terra nigra platter (Camulodunum type 8: A.D. 25–60). stamped IVLOSAV(OTIS): X. These eight graffiti. though slight, are interesting because of their early date (A.D. 35–50).

31 For a sketch-plan of the enclosures see Britannia 23 ( 1992). 290. fig. 19.

32 The reading of A is very uncertain.

33 The first letter is C. not G.

34 During excavation directed by Prof. Barry Cunliffe for the Danebury Trust as part of the Danebury Environs Roman Project. Emma Harrison made the object (HO 97 318 3165) available.

35 For similar ‘stars’, but less denarius-like since they have three intersecting lines of equal length, see RIB 11.3. p. 106.

36 During excavation directed by Prof. Barry Cunliffe for the Danebury Trust as part of the Danebury Environs Roman Project. Emma Harrison made the object (TH 02 F1066/1 3210) available.

37 The final letter is damaged and now incomplete, but there would not have been room for M (instead of IV). nor for S after V. Atecius. a name of Celtic etymology, is found in CIL v. and may be that of a samian potter (CIL vii. 1336. 97): it is not attested in Britain as that of a brooch-maker, nor in G. Behrens. ‘Römische Fibeln mit Inschrift’, in G. Behrens and J. Werner (eds). Reinecke Festschrift (Mainz 1950). 1–12.

38 By the present owner, a London dealer in antiquities, who made it available.

39 Transcribing the letters as New Roman Cursive (note especially the forms of A. B(?). E. R, M and V); thus later than the mid-third century, and probably fourth-century. Since the text is not recognizably Latin, the letter-forms cannot be confirmed by context, but two 4-letter groups in the centre, VCCV and RVVI. seem to be certain. They may be a Celtic personal name and patronymic: compare RIB 1548, deo Veteri votum Uccus v(ovit) l(ibens); the related forms Uccius and Uceo (derived by Holder from *Uccu) are well attested. For the possible patronymic compare CIL iii. 3821 (Igg, Pannónia Superior), Emme Ruiifliliae) iixo(ri). Before VCCV the 4-letter group is possibly BONA, suggesting a place-name ending. After VCCV RVVI there are four groups of letters, each beginning with E: the second E is capital in form, the others cursive and ligatured to the next letter, where M looks all right, but O is more conjectural. Therefore the graffito may be the potter's signature, but apparently not in Latin.

40 With the next three items during excavation by MoLAS directed by Pete Rowsome and others. RSOT will publish them with some illegible fragments in Rowsome's final report.

41 For the text and commentary, with a line-drawing and photograph, see above, pp. 41 ff. See also Salway, B.. ‘Slave sale contract from London revealed’, British Epigraphy Society Newsletter, n.s. 9 (spring 2003). 10–11.Google Scholar

42 For another example see RIB II.4, 2443.1. It might also be improvised by breaking an ordinary tablet into half: see RIB II.4, 2443.6 and 10.

43 The most likely cognomen is Marciamts. but Martianus and Mucianus are also possible. Septimius Silvanus presumably included his own praenomen. This ‘address’ is of the standard form (‘To ABC from XYZ’ ) often found in the Vindolanda Tablets: for stilus-tablet examples see Speidel, M.A.. Die römischen Schreibtafeln von Vindonissa (1996). Nos 29. 49 and 52.Google Scholar

44 The two ‘pages’ were hinged together, their left-hand edge now lost, the inscribed text continuing from the first ‘page’ to the second. At the top of the first ‘page’ there is too little to confirm the expected letter opening (‘Silvanus to M[…]ianus. greetings’), but in the bottom right-hand corner of the second ‘page’ the letters AL can be read, which might belong to the concluding formula VALE (‘farewell’). The last word of the first ‘page’ is apparently NVNQVAM (‘never’), crammed into a confined space. Two lines above it, the line may end with NVMEROS (‘numbers’ or ‘units’).

45 The tablet was evidently re-used as a letter to Sabinus. After SABINO the letters are too incomplete to be read securely. but they might be CE/LERIA. This would suggest the writer's name. Celeria[mts]. but the remaining traces of the second line do not support it. Sabinus may have been identified by his occupation or military rank/function.

46 Part of an ‘address’, the beginning unless the tablet has been cut in half (since CLERO is more like the end of a name than its beginning).

47 With the next three items during excavation by MoLAS directed by Nick Bateman for the Corporation of London. Fiona Seeley made them available to MWCH.

48 The last letter might be a compressed N, but other letters commencing with a vertical are not in question.

49 For the personal name Nonnus compare No. 39 below, with n. 67.

50 The graffito is probably complete. The cognomen is well attested in Britain: see RIB II.2, 2417.39; II.7. 2501.531; II.8, 2502.23; and, as Tacita, RIB 221; RIB II. 1, 2409.36 and II.8, 2501.530.

51 In white ware from the region of Verulamium, dated A.D. 50–160.

52 (b) was conceivably intended to complete (a), a blundered Crescenti (‘for Crescens’) or Crescentiani, but (b) is very unclear.

53 During field walking by Alan Womack, in whose possession it remains. Andrew Rogerson of Norfolk Landscape Archaeology, Gressenhall, provided information and images of this and the next item (No. 31).

54 By a metal detectorist. The owner, Neil Foster, has given it to Norwich Castle Museum. Adrian Marsden, finds liaison officer for Norfolk Landscape Archaeology, made it available to MWCH, and provided the reading of (b)5, part of the name of the recipient's unit.

55 We thank Giles Standing for identifying the unit in line 2. It is not a Cohors Campestris or Campanorum since the letter preceding CAMP is probably R and certainly not part of a numeral; and Campestris is further excluded because the letter after CAMP looks more like A than E. The ala I Hispanorum Campagonum is attested in Pannonia Inferior in A.D. 114 and in Dacia Superior in A.D. 144, 157 and 158, by RMD No. 153, CIL xvi. 90, 107 and 108. However, no unit of Pannonians (like the recipient's) is attested in Pannonia Inferior by the diplomas of A.D. 114 or 110 (RMD No. 153; C/Lxvi. 164), while the ala I Hispanorum Campagonum is not attested in any diploma for Roman Britain. There are at least two possible explanations, (i) This is a diploma for Pannonia, the recipient having been recruited into a Pannonian unit then serving in Britain which was transferred to Pannonia Inferior (where, however, it is as yet unattested), the recipient returning to Britain when discharged, (ii) This is a diploma for Britain, inherently more likely, implying that the ala I Hispanorum Companorum served in Britain before leaving for Pannonia Inferior, perhaps after 110 (since it is not attested there by CIL xvi. 164) but before 114 (when it is attested by RMD No. 153). The recipient would then have served in either the ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana or the ala I Pannoniorum Sabiniana, both of them attested in Britain by CIL xvi. 69 (A.D. 122). This possibility, if accepted, would add a new unit to the army list for Britain, the ala I Hispanorum Campagonum.

56 For the unit, see the previous note. This is the usual formula restrieting the grant of citizenship, followed by the consular date; Trajan is given the filiation which he lacks in the comparable position in CIL xvi. 42, although both diplomas were issued in the same year.

57 By a metal detectorist, who has given it to the Museum of Antiquities, Newcastle-upon-Tyne (ace. no. 2002.14). Lindsay Allason-Jones sent photographs and other details.

58 The obverse numeral is emphasised with a forked lower serif and three diagonal strokes above the suprascript bar. This is the first known sealing of the cohort, which was the third-century garrison of High Rochester (Britannia 25 (1994), 51). The reverse impression may also be legible, but it is too shallow and damaged along the bottom edge to be read from the photograph; it is evidently an abbreviated personal name.

59 Found (inv. no. 8321) with the next seven items during excavation for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Andrew and Robin Birley, who made them available.

60 (Inv. no. 8662.) The first letter might be Q without its tail, but there is no evidence lor a name *Quincus (the C is certain), whereas a Celtic personal name Ovincus can be deduced from CIL iii. 5139 (Noricum, near Celeia), Sa.ssus Ovincii fiiliusj and CIL vi. 2613 (Rome, a praetorian guardsman), P. Ovinconius P. f. pol. Ingenuos domo Badineomagus.

61 (Inv. no. 8688.) X is much the most common ‘numeral’ found on bone roundels (see RIB 11.3, pp. 105–7); compare Nos 41 and 42 below. Its significance is uncertain, but on a counter it is more likely to be the numeral ‘10’ than a mark of identification. On face (b), R has been scratched twice. For another example of the cognomen Ve rax see RIB 1057 (South Shields), a legionary centurion.

62 Robin Birleymade it available, but identification, reading and interpretation are by Élise Marlière, University of Lille. For the amphora form see below. Addenda et Corrigenda (e).

63 (Inv. no. 8487.) Two redundant strokes are associated with M, the first possibly a confusion with A, but both may be dismissed as casual. The owner is identical with ‘Tagomas vexellarius’ in a writing-tablet found nearby in 2001: graffito and tablet are illustrated in Current Archaeology 178 (March 2002). 444–5. He is already attested as the vexillarius Tagamas in Tab. Vindol. II. 181.14–15.

64 During excavation for the Vindolanda Trust directed by Robin and Andrew Birley, who made it available (inv. no. 7877) with a draft description and analysis by Anthony Birley. Illustrated in colour in Current Archaeology 178 (March 2002), 443.

65 These sometimes differ in quality and are unrelated to the text, for example the ‘diagonal’ descending from the second letter on line 1, but they are difficult to eliminate because of the laxity of the lettering and its uncertain interpretation.

66 The graffito is not obviously a list of names, firing-tally or date, and the ambiguity of the letters makes any interpretation still more arbitrary. Line 1 might be the end of a personal name in the ablative case, qualified as pfrae)p(osito) (‘superintendent’). Line 3 might be part of a numeral inscribed over A. Line 4 might be the end of Maximo, even followed by the numeral 11 (instead of T in 5), displaced because of the ‘signature’, but it would be difficult to accommodate the implied consular date (A.D. 103).

67 (Inv. no. 8749.) The graffito is complete: after L. it seems that 1 was omitted and S written without its tail. The two cognomina may be those of successive owners, but they seem to belong together, and thus to be name and patronymic. The name Genialis is common among soldiers, and the patronymic may have been needed to distinguish homonyms: for examples of Genialis ‘pairs’ in the same unit, see RIB 109 and Tab. Litguval. 1 and 16 (Britannia 29 (1998), 42 and 57–8). Nonnus is mostly found in Celtic provinces: for the only British instance see RIB 932.

68 G (not C) has been written with three strokes, as in the contemporary writing-tablets: see Bowman, A.K. and Thomas, J.D., Vindolanda: the Latin Writing-Tablets (1983), 63.Google Scholar In view of the bowl's early date, Andangius was probably a Tungrian or Batavian; his name otherwise has Rhineland associations: compare CIL xiii. 7086 (Mainz), Gamuxpero Andangi (filio) and CIL xiii. 2945 (Sens), Andangianius Tertinus, a veteran married to a woman of Cologne. This association of names now suggests that [Gamujxperus, not /…U]xperus, should be restored in Tab. Vindol. II, 184.23.

69 With the next seven items during excavation for Tyne and Wear Museums directed by N. Hodgson, G.C. Stobbs and G. Brogan: see Britannia 32 (2001), 322–4 and 33 (2002), 290–91. Alex Croom made them available, except for the two samian sherds (Nos 44 and 47) of which there were only photographs. RSOT will publish them in the final report with other graffiti too slight for inclusion here, since they are less than three consecutive letters, or doubtfully lettered, or only ‘marks of identification’.

70 X is much the most frequent ‘numeral’ to be scratched onto bone roundels found in Britain (see RIB II.3, pp. 105–7); compare the next item (No. 42) and No. 35(a) above.

71 The first stroke might be part of N or V, but the sequence of letters does not suggest any likely name. Another possibility is that the first two strokes are an incompletely-formed O; this would then suggest [m]odii Vll[…], ‘seven (or more) modii’, the average capacity of a Dressel 20 amphora.

72 The sequence of strokes cannot be determined from the photograph, but the graffito was probably made as usual in this position, with the vessel inverted. The graffito might be a single letter, but is more likely to be an abbreviated name such as [CA]N or [IA]N.

73 The nomen Iulius is quite often used by soldiers, especially legionaries, as a cognomen: see Britannia 29 (1998), 64.

74 Presumably part of a numeral, perhaps of capacity.

75 The nomen is very common, but here it is presumably a cognomen.

76 Galatea is a feminine name of Greek etymology, suggestive of a slave or freedwoman. This is its first occurrence in Britain, but it is well attested in CIL v (twice) and CIL vi (four times), in all but one instance explicitly the name of a freedwoman.

77 During excavation for North Tyneside MBC directed by N. Hodgson: see Britannia 30 (1999), 334–9. and N. Hodgson, The Roman Fort at Wallsend: Excavations 1997–8, (2003). We have not seen the original (WSCA689), but Alex Croom provided a drawing, colour photographs and an X-ray photograph.

78 Only the sequence from P to M is visible, but underneath the corrosion, in the X-ray photograph, there is a possible trace of initial T, certain evidence of ARC, and then trace of C. 4 more letters. Two names can be recognized, PRVSO and MARC[…]. Pruso is a Celtic personal name (see CIL xiii. 6294 and 6310, and compare 4579 for Prusonius), appropriate to an eques or decurión of Gallic origin in acohors equitata. It is followed by some cramped letters which can be read as LANA for -(n)iana, identifying the turma by the adjectival form of the last decurion's name when its command had become vacant. The traces after MARC are faint and confusing; the last letter looks like S, but Marcellus or Marcianus cannot be read.

79 By a metal detectorist who has sold it to Landrindod Wells Museum. Published (but with ‘Specialist comment awaited’) by Britnell in Britnell, J.E.et al., ‘Recent discoveries in the vicinity of Castell Collen Roman Fort, Radnorshire’, Studia Celtica 33 (1999), 33–90Google Scholar, at 71, No. 21 with 72. fig. 13. We owe this reference to Prof. Sheppard Frere.

80 Similar to, if not identical with, the well-attested reverse of a sealing of the nearest legion, legio II Augusta: RIB II. 1. 241 1.59–62 (Brough under Stainmore). FIT is unexplained. It is not an abbreviated verb or tria nomina, but it might be an abbreviated name like F(…ius) It(alicus).

81 Knox, John, A View of the British Empire (3rd edn, 1785), 611–12Google Scholar, footnote. We owe this reference to Prof. Lawrence Keppie.

82 Neal, D.S. and Cosh, S.R., Roman Mosaics of Britain, I (2002), 353–6Google Scholar, Mosaic No. 143.2. This corrigendum derives from discussion with Prof. Roger Wilson; see above pp. 288–9.

83 This was Richmond's reading, as the apparatus notes, and it was preferred by Toynbee (Britannia 8 ( 1977), 479) and by Colin Smith (ANRW II.xix (2), 908, n. 14), who notes that FLAMMIFER would be the Classical form, but that unstressed (short) ‘i’ and ‘e’ fall together in Vulgar Latin. This reading is also more compatible with Wright's 1951 drawing and Neal's 1962 painting, both of them made before the mosaic was lifted, than is F[R]AMMEFER (‘spear-bearing’), which the editors of RIB II took from Collingwood and Wright. RSOT noted that the supposed trace of R ‘is not borne out by the drawing’, and he now finds that it is not supported by Wright's contemporary notebook either. The analogy of armifer (etc.) makes it difficult to derive any sense of ‘pierced by a spear’ from *frammefer <framea (‘spear’). The mosaicist has used red chips to outline the lion's mane, the piercing of its back, and the streams of blood, but he may have misunderstood a millet stalk in the drawing he used: compare Witts in Britannia 25 (1994), 112–13, with pl. VI.

84 Breeze, A., ‘Does Corieltavi mean ‘army of many rivers“?’, Antiq. J. 82 (2002), 307–10CrossRefGoogle Scholar, where RSOT is the anonymous referee quoted on p. 308. Sheppard Frere adopted the form ‘Corieltavi’ without explanation in the third (revised) edition of Britannia (1987), but Breeze now reconciles the Corieltauui of the Caves Inn graffito with the literary evidence, Ptolemy's variant Contavi and Ravenna's Rate Corion and Eltavori, by explaining its -uu- as a hypercorrection or perhaps ‘an attempt to represent a Latin sound resembling English W’. This admits the attractive etymology from Celtic *Tauia (‘Tay’, i.e. ‘river’, with semi-vocalic u and i).

85 R.P. Wright read COHVGG: ‘the final G is faint but definite’, which he interpreted as G(ordiana). This was questioned by Alex Croom, who showed the tile (T66 DK.2) to RSOT. The published drawing is inaccurate: after COHVG there is a circular projection and part of a concentric ‘rim’ above it, certainly not G, which correspond to a circular depression before COH, this pair of marks being due to the ends of the pegs which secured the wooden die to its handle. They are visible on many of the cohort's stamped tiles (RIB II.4, 2473.1–6).

86 By Élise Marlière, University of Lille, as Robin Birley has informed RSOT. Dipinti identify the contents as black olives and defrutum. Compare item No. 36 above.

87 By RSOT in preparing his contribution to the definitive publication by Catherine Johns. For an interim report of the inscriptions see Britannia 25 (1994), 306–8, Nos 41–60.

88 Pin both graffiti is of ‘capital’ form, as usual in New Roman Cursive, but Rin (a) is ‘capital’, in (b) it is ‘cursive'. Both forms are found in New Roman Cursive: see Tab. Sulis, p. 94. The graffiti are presumably the abbreviated personal names of successive owners.

- 9

- Cited by