Introduction

Stećci gravestones (singular stečak) are remarkable medieval monuments located in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro (Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009). The number of these monuments is substantial; over 70 000 stećci are currently recorded in the Western Balkans, with more than 60 000 found in Bosnia and Herzegovina alone (Figure 1). Despite their abundance, however, these monuments and their purpose are unfamiliar to the broader European public. They embody centuries of Bosnian tolerance, which has developed from the long-term local coexistence of diverse ethnicities (Delanty Reference Delanty2013) and multi-faith communities following religions that include Orthodox Christianity, Roman Catholicism, the Bosnian Church (Christian, although proclaimed heretical) and Islam. Remarkably, stećci are not attributed to a single ethnic or religious group and have always been considered enigmatic, lacking a clear, explicit belonging (Bešlagić Reference Bešlagić1982; Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009). A Marie-Skłodowska-Curie-funded project (SOLMUS) examines this impressive funerary heritage to understand the complex social lives of the societies that created it.

Figure 1. The distribution of approximately 3300 sites of stećci monuments in the Western Balkans (adapted after Bešlagić Reference Bešlagić1971).

The medieval funerary heritage of the Western Balkans

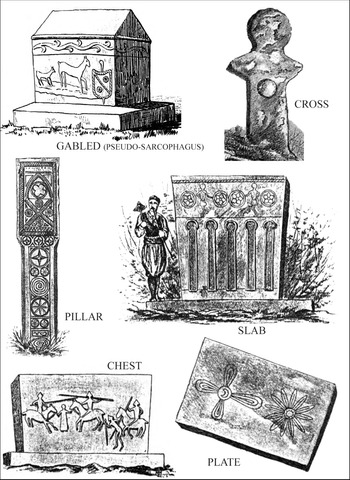

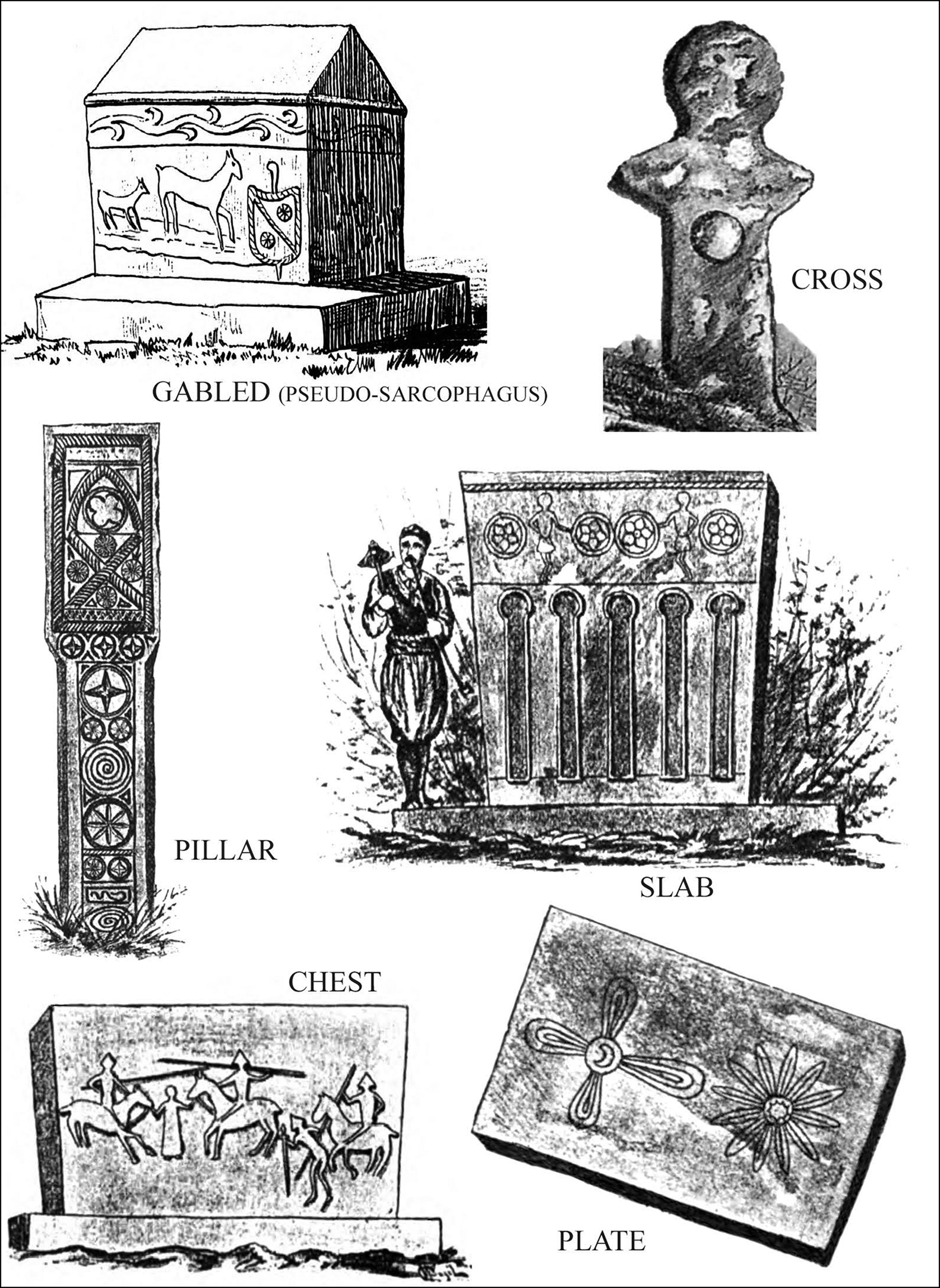

Evidence suggests that stećci first appeared in the twelfth century and were in use until the sixteenth century. They characterise a specific funerary phenomenon and represent a unique amalgamation of traditions, religions, and artistic and aesthetic expressions, as well as languages. Their morphology varies immensely, from pseudo-sarcophagi to crosses, slabs and plates, chests and finally pillars (Figures 2–4; Bešlagić Reference Bešlagić1982; Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009). Approximately ten per cent of these monuments have decorative iconography that represents both unique local traditions and motifs found in other regions of medieval Europe. Decorations in low relief consist of abstract motifs, celestial bodies, human and animal figures, weaponry and floral decorations (Wenzel Reference Wenzel1965, Reference Wenzel1999). Only a minute number of stećci have inscribed epitaphs, and these follow ancient Greek (Wolfe Reference Wolfe2013), and Roman epitaph formulas (van der Horst Reference van der Horst1991). Although the epitaphs mostly reference the classical style, the language is Slavic and inscribed in either early Cyrillic or Glagolitic scripts, neither of which remains in use today (Vego Reference Vego1962–1970). Regional variations of stećci are evident in the forms, ornamentation, epitaphs and the quality of craftsmanship (Wenzel Reference Wenzel1965; Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009).

Figure 2. The six main forms of stećci tombstones (de Asbóth Reference de Asbóth1890).

Figure 3. Stećci necropoles Goršića polje by Goražde and Radimlja (courtesy of Edin Bujak and www.nekropola.ba).

Figure 4. Stećci necropoles Blidinje-Jablanica and Gvozno-Kalinovik (courtesy of Edin Bujak and www.nekropola.ba).

Studied extensively by historians, stećci remain vastly under-studied by archaeologists. The sheer number and wide distribution of the tombstones has hampered detailed scholarship. Out of approximately 3000 stećci sites in Bosnia and Herzegovina, few have been the subject of archaeological research. The initial apperance of stećci remains obscure and debated. Some theories link them to megalithic traditions, while others see them as representing Romanesque or Gothic-style urban or rural houses, or local medieval Christian sarcophagi (Purgarić-Kužić Reference Purgarić-Kužić1996). Why they appeared in the twelfth century, what triggered their initial creation, and the presence of precursors remain largely unknown (Wenzel Reference Wenzel1962; Bešlagić Reference Bešlagić2004; Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009). The earliest stečak, dated by its inscription, is that of Grdeša, the mayor of Trebinje (AD 1151–1177) (Purgarić-Kužić Reference Purgarić-Kužić1996). Current knowledge of the origins of this UNESCO-protected heritage, in particular dating evidence, is, however, limited by the state of research—stećci that have been excavated all post-date Grdeša's tombstone. The uncertain origins of stećci have prompted the development of three theories (Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009). The first, based on religion, holds that they were erected by supporters of Bogomilism, the Gnostic dualist social-religious movement or by the heretical dualist Bosnian Church. The second relates to a common ethnicity and claims parallels to the native Vlach population (Figure 3). Finally, the social theory links the tombstones to elite social groups. The latter is improbable given the quantity of stećci, yet only a systematic study will further illuminate any of these theories.

The number of stećci in a cemetery is an important indicator of social trends in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina (Figure 4). Historical studies have proposed three types of cemeteries, based on the number of stećci: cemeteries with up to ten stećci are believed to represent family burial grounds; clan necropolises are marked by 30–50 stećci; and cemeteries where stećci number in the hundreds represent entire communities. Small cemeteries should represent later medieval society, after the collapse of clan-based groups saw the emergence of family communities, with smaller burial grounds, marking their new identity as a family unit (Lovrenović Reference Lovrenović2009).

Social landscapes of multicultural spaces (SOLMUS)

The SOLMUS project is gathering new data to tackle questions relating to death, burial and memory, the dynamics of landscape and political complexity, and how these factors relate to religion and society. The extraordinary numbers of stećci provide the data for qualitative spatial assessments of social, religious and political dynamics in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Balkans more broadly.

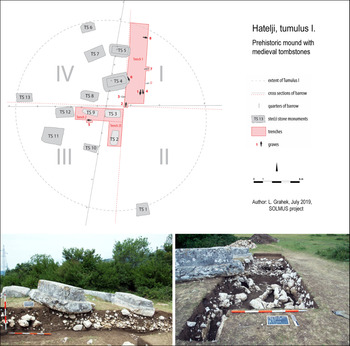

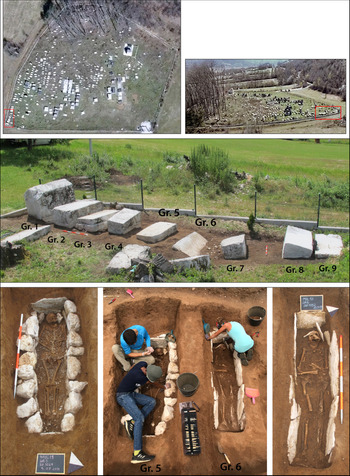

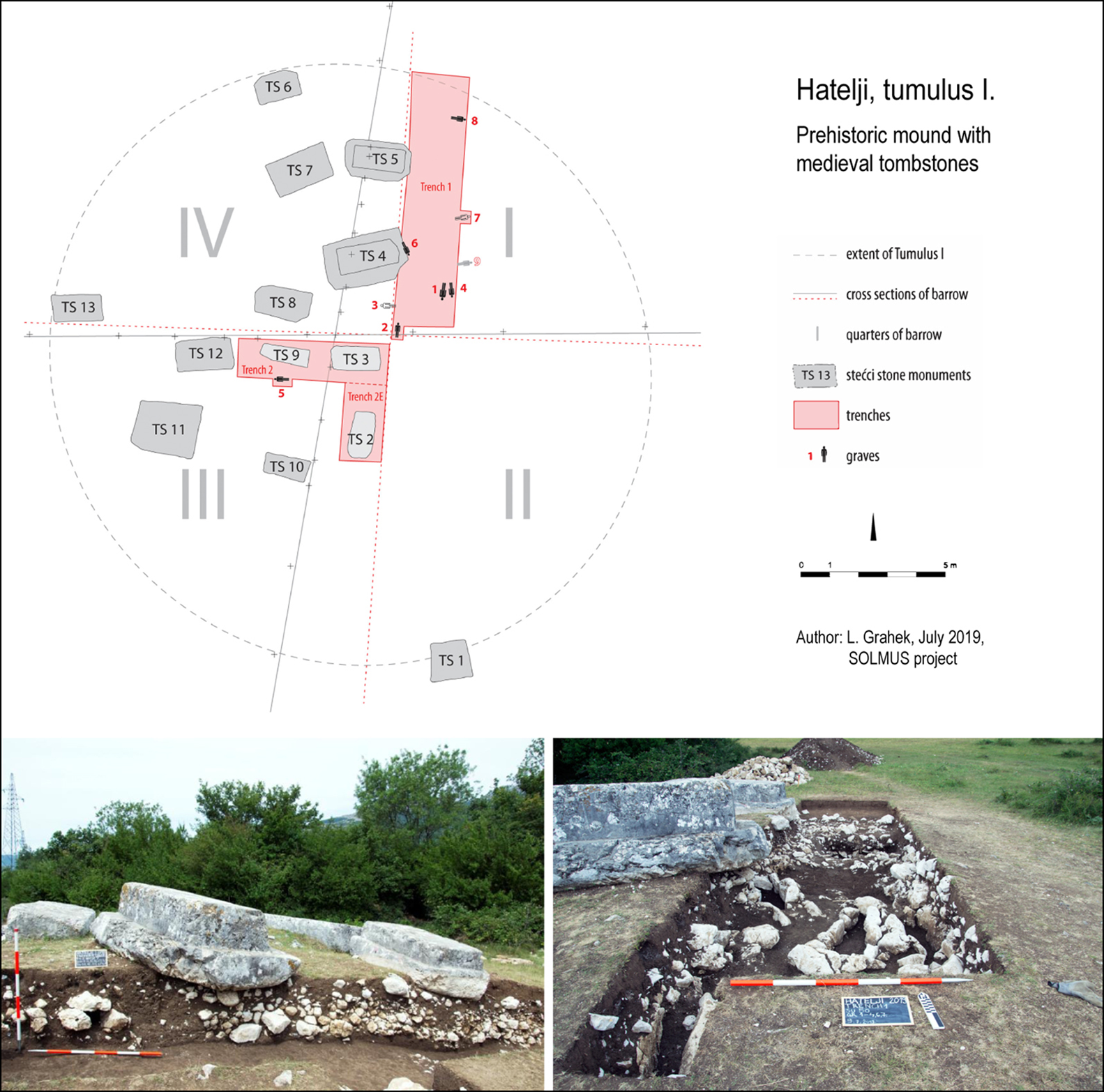

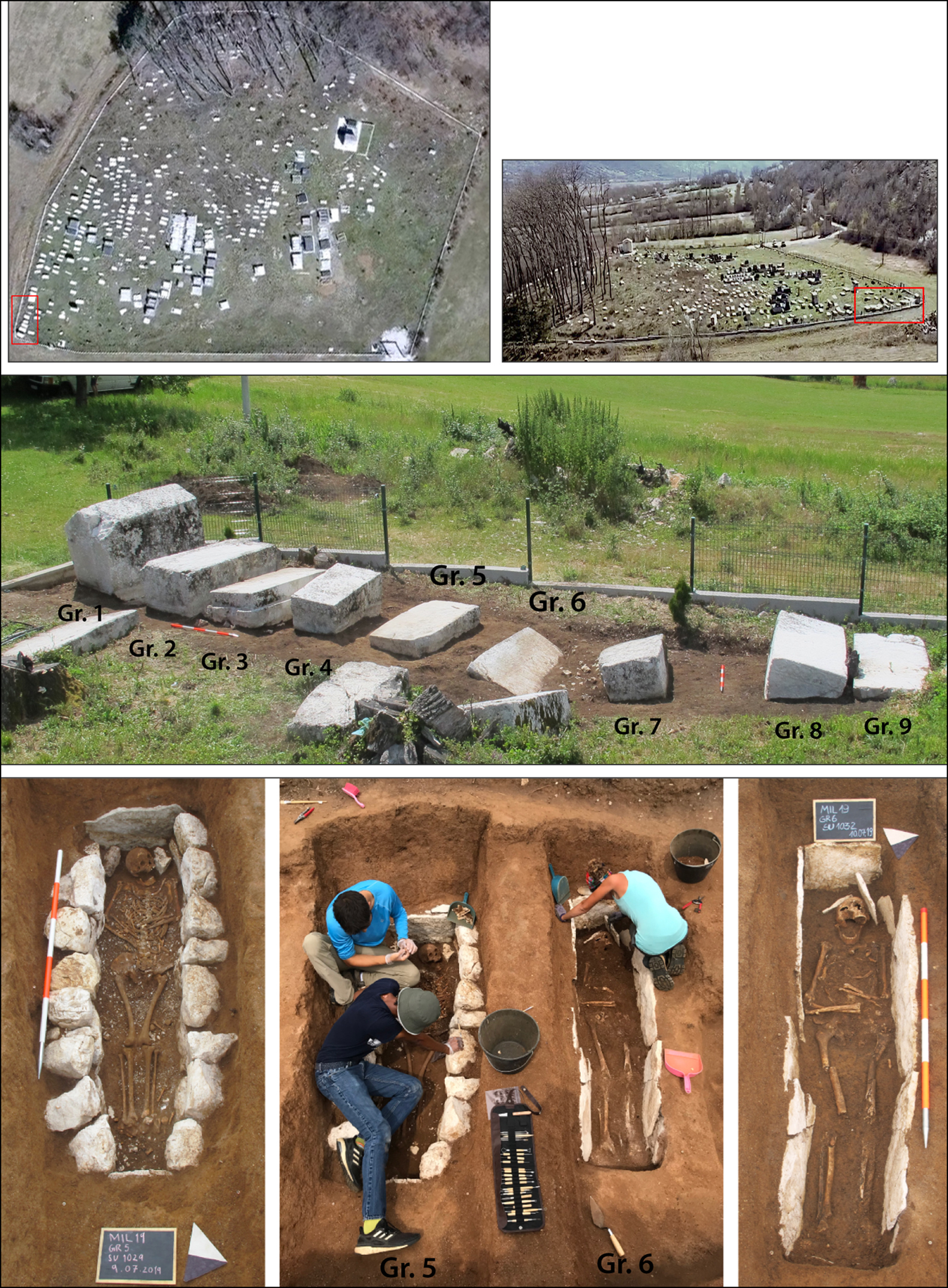

This project focuses on the medieval župa Dabar in Herzegovina as a case study. After settling in the Balkan Peninsula, Slavic tribes created tribal territories called župas. A župa is an administrative-territorial unit, formed on the basis of the natural and social environment, thus incorporating rivers or streams, valleys and important roads and settlements into its boundaries. One such župa was formed within the karst landscape of Dabar Valley and its adjacent hills. The first historical reference to the town of Dabar, the seat of the župa, was in the tenth century when it was referred to as Dobriskik by the Byzantine emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus, but the location of the town has remained undetermined. The demographic and economic history of the župa was examined in detail through medieval documents at the National Archive in Dubrovnik, Croatia (Pekić Reference Pekić2005). Within the territory of the medieval župa 47, stećci necropolises with 1438 monuments in total (the deathscape), and 17 villages (the livescape), were identified (Bešlagić Reference Bešlagić1982; Pekić Reference Pekić2005). The SOLMUS project has conducted archaeological surveys of the whole župa, with geophysical survey undertaken at seven necropolises and excavation at two. These are Hatelji, a smaller cemetery with 13 tombstones, located on a prehistoric mound (Figure 5), and Milavići, a large communal multiperiod necropolis with 352 medieval monuments (Figure 6; Čaval Reference Čaval2019).

Figure 5. Hatelji site: map of the prehistoric mound with medieval tombstones and trench one during the excavations (SOLMUS Archive).

Figure 6. Milavići site: view of the cemetery with the studied area and excavated graves five and six (SOLMUS Archive).

The project approaches this vast corpus of data with increasingly greater precision, investigating the sepulchral phenomenon at multiple scales. Considering a tombstone with inhumation burial as one unit, the project navigates from large-scale landscape assessments to a high-resolution analysis of individual graves. Linking together innovative social archaeological interpretations of the past with social and landscape modelling, the project is examining the agency of stećci in constructing and reshaping medieval social and religious worlds, and their role in the formation of social memories.

Acknowledgements

The project is supported by the University of Reading, the National Institute for the Protection of Historical, Cultural and Natural Heritage Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, especially L. Srdić and L. Vručinić, and the municipalities of Berkovići and Bileća.

Funding statement

The project is funded by the Horizon 2020, MSCA-IF-2017 (797881).