‘By turns baleful and benign,’ writes Tristram Besterman in the Preface to this extraordinary book,

Alderley Edge seems uncannily to demand our attention, exerting an extraordinary influence over countless lives through the turn of the centuries. This might help to explain why so many facets of one place have now been subjected to such intense, prolonged and expert scrutiny.

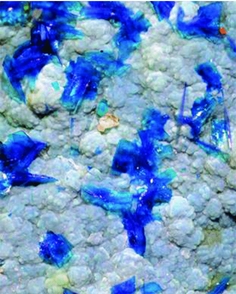

Or as Wikipedia tells us, Alderley Edge is a sandstone ridge in east Cheshire, at the foot of which is ‘one of the most expensive and sought-after places to live in the UK outside central London’. The Edge is known for more than its renown as England's champagne capital. It is rich in minerals, and down the years has been riddled with miles of tunnels and shafts by people who sought them; it is a place to meet a stranger, and beneath it is a sleeping army led by a hero waiting for the last battle of the world; it was a cradle of prehistoric metalworking; it is a literary landscape, the scene of Alan Garner's Stone Book Quartet and three of his novels; and as Garner shows in the penultimate chapter, leaving you stunned, all these things are linked.

The story of Alderley is the fulfilment of a multi-disciplinary collaborative campaign of field research that was conceived over 20 years ago. It called itself the Alderley Edge Landscape Project, has already produced reports on The archaeology of Alderley Edge (2005), The Alderley Sandhills Project (2010) and an educational website for young visitors, and has inspired other publications such as Matthew Hyde's The villas of Alderley Edge (Reference Hyde1999). The collaboration began between the National Trust (which is steward of much of the Edge) and the Manchester Museum, but expanded to include scholars from six universities, wildlife groups, local historians, ecologists and the Derbyshire Caving Club. The book itself has a kind of geological heft, with so much in it that when you arrive at the end of the editor's Envoi on page 780 there are still 204 pages of appendices and apparatus to go. The scale is biblical. Production values are high, and John Prag's editorial coordination of contributions from its 34 authors (31 chapters, 13 appendices, glossaries) is a tour de force in its own right.

There are six parts. In the first are introductions, to the Project (from John Prag), and a personal view of the Edge from Alan Garner, for whom the Project started in childhood. Prag re-tells the story of Garner's re-discovery and curation of an oak shovel in a climate of academic disbelief and its eventual dating to the early Middle Bronze Age. All students of landscape, perhaps all students of anything, should read Garner's ‘Approach to the Edge’, which, along with much else, brings science face to face with realities “that perhaps may not be spoken, only felt” (p. 40). This staredown is followed by an exquisite paradox in which reports retrieved by the Project of music heard from under the ground are juxtaposed with an ‘age-old’ tradition of witchcraft that demonstrably dates only from 1962. Bogus history and fake news walk hand in hand; in Garner's world, the primary challenge to falsehood is not fact, but the Edge itself.

Facts nonetheless follow, and plenty of them. In Part II, ‘The bedrock of the Edge’, five chapters take us through the geological and geomorphological story, the minerals, the evolution of the landscape, the effects of ice, concluding with a return to warmer conditions, the formation of soils and regrowth of vegetation. The scene is thus set for Part III, ‘Natural history—the flora and fauna’, which are studied through a division of the Project's core area into 54 land parcels that enable statistical comparison. Part III embraces the trees, plants, mosses, liverworts, algae and fungi with which the Edge is clad, and the birds, water creatures, insects and myriad invertebrates that live among them. It is virtually a book in itself. The insects alone occupy nearly 100 pages. The naturalists have shown that what grows, flies or buzzes on the Edge is to a very large degree a function of human activity. People made way for heathland by felling native woodland in the early Middle Ages; later landowners re-wooded the heath with new species in successive episodes of tree-planting. Botanical fashions around nineteenth-century villas, vegetable plots beside evanescent industrial housing, the geo-chemistry of mining and quarrying spoil—each and all have interacted in a continuum that leads to the biota we see today. Yet alongside change, in a kind of stillness, our attention is drawn to species such as Wavy Hair grass and Bilberry that may have grown continuously on the Edge since prehistory.

Having escorted people onto the scene, nature gives way to culture: archaeology, mining and quarrying in Part IV, social history in Part V. Much of Alderley's archaeological story was told in the Project's 2005 volume. Here, Prag and Timberlake give a condensed and updated appraisal. The evidential base is curiously patchy: substantial and tantalising in the Mesolithic, vivid in the Early Bronze Age, at other times often puzzling or scanty. Surprises abound. The Roman scene, for instance, was ‘rather bare’ until the finding in 1995 of the first Roman mineshaft to be discovered in Britain. There is even a classic Alderley coda involving the pop-up discovery of a post-medieval wooden grail-like vessel that might have been a prop for local Christmas performances. (Apropos of which, given Alderley's pre-eminent status as a place of legend and stories, one of the work's few historical oversights is the Cheshire volume in the series of Records of Early English Drama.)

A recurrent consideration in The story of Alderley is what methodologies might be found in response to the tendency in mining/quarrying landscapes for each episode of activity either to subtract from what was there before or to muddy its signs. The following thematic chapters take up the challenge. Timberlake examines evidence for mining from prehistory to the seventeenth century. Warrington explores mining, industry, their sources and processes between c. 1600 and the 1920s. Dibben considers Alderley's 100-plus shafts and adits from the standpoint of the cavers who have been surveying them, summarising evidence for some 30 quarries and their associated micro-archaeology of tooling, slots, glyphs and cutters’ marks.

In Part V we encounter Alderley down to the present through cross-weaving written records, buildings, the Stanley estate, the names of houses, streets and fields, graffiti and oral memory. At 10 chapters and 377 pages this too could have been a book itself, and aside from being informative, parts of it make joyful reading. Matthew Hyde's account of the first wave of villa-building (c. 1842–1870) leads us through the processes of plot selection (views, romantic backdrops), sizing, drainage and the pied styles (‘Italianate, Tudor, Gothic, castellated, Swiss’) that clad structures which in reality were mostly of standard plan. Hyde reminds us that until the Manchester and Birmingham Railway opened a station in 1842, there was no settlement called Alderley Edge. The station was liked by well-off commuting Mancunians, so the colony grew, and to the Stanleys’ displeasure, so did use of the name. Nonetheless, there were two townships of Aldredelie in 1086 (corresponding with today's Nether and Over Alderley), sub-tenanted by Norman lords who held them as parts of larger constellations of estates. Discussion of them would benefit from fuller and current contextualisation—reminding us that one of the challenges in a project that runs for decades is keeping up with intellectual developments elsewhere.

Part VI, ‘Looking back, looking forward’, begins with Christopher Widger, the National Trust's Countryside Manager for Cheshire and the Wirral, reflecting on what the book means for stewardship of the Edge. This is a huge task, and phrases near the opening (‘engaging with supporters’, ‘optimising access’, ‘Conservation Performance Indicators’) may make you wonder if National Trust jargon will be sufficient to express its complexities. When Widger turns to discuss the many co-varying factors (even the weather) that affect the annual impact of over 200000 people, however, his care and commitment to the Edge jump off the page. The challenges of heritage management are as iron upon which is struck the flint of the next chapter, Alan Garner's essay ‘By seven firs and goldenstone: an account of the legend of Alderley’.

If you have read The weirdstone of Brisingamen you will know the story. A farmer takes a white mare to sell at Macclesfield market; dawn finds them crossing the Edge, where the horse stops and “a tall old chap, thin as a rasher of wind” (p. 762) steps forward and asks to buy her. The farmer refuses; the old man tells the farmer that he will find no buyer at Macclesfield. This turns out true, and when the farmer returns the old man is waiting. He touches a rock with his stick and splits it open, “And behind the rock there's some iron gates” (p. 763). The man escorts them down into the hill where knights lie “all asleep with their heads each against a white horse, except one” (p. 763). The white mare is taken in exchange for treasure, but when the farmer returns next day for more, the iron gates are not to be found. What the essay goes on to show is that every detail in the story has precise meaning that maps both onto the historical topography of the Edge and to royal inauguration rituals that go back at least to the first millennium and arguably over 4000 years. The Edge is where mining, magic and memory meet.

The story of Alderley, then, is less a book than a kind of library that centres on one place, but does so in ways that illuminate and interact with themes of continental span. As with all libraries, it is not just a storehouse but a place for new study. At the end of his editorial preamble, John Prag reflects on 20 years’ obsession with the work, and hopes that his wife will be pleased to see it done. Mrs Prag should not hold her breath. Epic as this work is, it is hard to imagine it as being anything other than the prelude to something yet greater.