Introduction

Ethnicity shapes political life in Africa, from voting (Adida et al. Reference Adida, Gottlieb, Kramon and McClendon2017; Ferree Reference Ferree2006) and the distribution of public goods (Ejdemyr, Kramon, and Robinson Reference Ejdemyr, Kramon and Robinson2018) to political violence (Montalvo and Reynal-Querol Reference Montalvo and Reynal-Querol2005). But whether ethnicity plays a similar role in African courts remains underexamined. Studies of judicial decision making in these contexts have largely overlooked the role of ethnicity in the courtroom, focusing instead on questions of socioeconomic inequality, regional disparities, and gender discrimination in judicial outcomes (e.g., Gloppen and Kanyongolo Reference Gloppen and Kanyongolo2007; Ndulo Reference Ndulo2011; Tripp Reference Tripp2004). However, judges in multiethnic societies typically navigate complex political terrain (Helmke Reference Helmke2002; Iaryczower, Spiller, and Tommasi Reference Iaryczower, Spiller and Tommasi2002), particularly in new democracies where the rule of law is often perceived to be weak or under threat (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell2004). Given these dynamics, for Africa in particular and the Global South more broadly, exploring the link between ethnic identity and judicial outcomes may help us understand how justice is delivered in ethnically diverse societies.

To date, research on the role of ethnicity in judicial decision making has largely focused on the American experience, highlighting how racial biases in American courtrooms undermine due process (Harris and Sen Reference Harris and Sen2019).Footnote 1 Yet, there are both theoretical and inferential benefits to studying judicial bias beyond the US context. Consider that very few societies have witnessed the domination of a single ethnoracial group for as long and with such impunity as white Americans, making the United States a somewhat unique setting in which to study group-based biases. Furthermore, these studies typically center around the dominant majority–minority cleavage (white-Black), which has restricted the ability of researchers to probe the potential heterogeneity in bias across different groups, thereby limiting understanding of the mechanisms underlying group-level differences.

Against this backdrop, the questions motivating this study are twofold: does ethnic bias affect judicial decision making in African courts? If so, what is the nature of and motivation for this bias? Building on the insights of social identity theory, we argue that ethnic favoritism in the courtroom results from the subconcious, implicit biases held among judges toward the appellants in a given case. That is, we contend that judicial bias along ethnic lines is driven by in-group attachments and out-group antagonisms. Framing ethnic bias in these terms represents a departure from conventional theories of ethnic politics in Africa, which more often portray ethnic favoritism as being driven by political or material considerations. In contrast to these works, we treat such bias as a by-product of historical, structural, and institutional factors that shape relations among ethnic groups rather than deliberate calculations serving instrumental goals.

To test our claims, we turn to Kenya, a relatively new democracy where ethnic divisions structure partisanship and patronage across the state (Kramon and Posner Reference Kramon and Posner2016), including within the legal sector (Odote and Musumba Reference Odote and Musumba2016). The Kenyan judiciary has recently become a locus of democratic contestation, ruling on presidential election controversies (Kanyinga and Odote Reference Kanyinga and Odote2019). Such cases highlight the instrumental dimensions of ethnic conflict in Kenyan superior courts, but whether identity shapes judicial decision making in quotidian legal proceedings remains underexplored.

We focus on criminal appeals in the Kenyan High Court: cases that are not overtly political (thus unlikely to be instrumentally motivated) and reflect day-to-day Kenyan jurisprudence. We built a dataset of almost 10,000 criminal appeals at 39 Kenyan High Court stations from 2003 to 2017. Our empirical approach leverages the fact that cases filed at a court station are assigned to individual judges based on the filing date and existing caseloads, independent of other case- and court-specific characteristics like judge and appellant identity. We rely on this conditional quasi-random assignment of cases to estimate the effect of judge–defendant coethnicity on the success of criminal appeals. To better understand the motivations for bias, we use word embeddings to measure levels of expressed trust (a marker of in-group favoritism) and disgust (a marker of out-group derogation) in written legal judgments.

Our analysis reveals significant evidence of coethnic bias in judicial decision making in Kenya. Across a range of empirical specifications, judges are between 3 and 5 percentage points more likely to rule in favor of a coethnic than a noncoethnic defendant. Yet these estimates mask significant heterogeneity across groups; effects are primarily concentrated among judges who are ethnically Kikuyu, Kenya’s largest and politically dominant ethnic group. We also show that judges express more trust sentiment in judgments for coethnic than non-coethnic defendants, consonant with notions that in-group favoritism and not out-group derogation motivates bias. These findings suggest that coethnic bias in Kenyan courtrooms manifests in the legal outcome and the judgment’s language.

Our paper makes several contributions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to systematically examine judicial decision making in criminal appeals in an African context. Research on African courts has predominantly focused on superior court politics, especially constitutional cases (e.g., Vondoepp and Ellett Reference Vondoepp and Ellett2011; Widner Reference Widner2001). While such cases are undeniably consequential, they are relatively rare, reflecting elite-level politics rather than how due process typically operates for everyday people. By focusing on criminal appeals, a more routine area of judicial decision making, our study addresses the broader challenges of ensuring free and fair justice for the citizens of new democracies in the Global South (Gibson and Caldeira Reference Gibson and Caldeira2003; Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009).

Second, we study implicit bias in a real institutional setting, building on existing lab-in-the-field work (Lowes et al. Reference Lowes, Nunn, Robinson and Weigel2015; Oppedal Berge et al. Reference Berge, Lars, Bjorvatn, Galle, Miguel, Posner, Tungodden and Zhang2020). Whereas existing work uses games and implicit association tests (IATs) to probe coethnic bias (e.g., Blum, Hazlett, and Posner Reference Blum, Hazlett and Posner2021), we consider identity-based bias in an important institutional setting—Kenyan appeals courts. In doing so, we show that the intensity of such bias varies across ethnic groups: consonant with social dominance theories, Kikuyu judges are the ones driving coethnic bias in appeals outcomes.Footnote 2

Third, to differentiate explanations of in-group favoritism and out-group derogation, we consider the empirical implications of social psychology work relating emotions to in-group versus out-group biases (Brewer Reference Brewer1999; Hodson et al. Reference Hodson, Choma, Boisvert, Hafer, MacInnis and Costello2013). We evaluate the mechanisms of bias through natural language processing techniques to measure affective patterns associated with favoritism or derogation (e.g., Rice and Zorn Reference Rice and Zorn2019). Our work joins recent work using text as data to understand the emotions, personalities, and states of mind of elites and citizens (Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis, Coan, Holman and Müller2021; Osnabrugge, Hobolt, and Rodon Reference Osnabrugge, Hobolt and Rodon2021; Ramey et al. Reference Ramey, Hollibaugh, Klingler and Hall2019).

Ethnic Identity and Judicial Bias in Comparative Perspective

Beyond Instrumentalism

To understand whether coethnic bias manifests in judicial decision making, we begin by problematizing the dominant account of ethnic identity in the developing world. An influential literature in comparative politics adopts an instrumentalist framework to theorize why ascriptive group identities become salient and why agents of the state may privilege coethnics (e.g., Bates Reference Bates1974; Chandra Reference Chandra2007). Focusing on contexts in which voters condition vote choice on the receipt of material inducements (Van de Walle Reference Van de Walle2001), scholars in this tradition argue that political elites favor coethnics in the provision of public goods because doing so advances the interests of important in-group supporters (Kramon and Posner Reference Kramon and Posner2013).Footnote 3

To what extent do instrumentalist theories generalize to the judiciary? Kenyan judges are not elected but appointed by the President, usually on the advice of the Judicial Service Commission. Although coethnic favoritism plausibly plays a role in judicial appointments, it is unclear why such considerations would translate into everyday judicial decision making. This is particularly true of cases concerning individuals with limited means to exert pressure on the courts, such as low-income persons involved in petty crimes or disputes. These cases do not concern significant political players, nor do they have an overt political agenda; judges thus lack clear incentive to rule a certain way. That is to say, there is no clear strategic rationale for judges to privilege coethnic over non-coethnic defendants when adjudicating everyday disputes.

While instrumental motivations seem largely absent in quotidian cases, judges may still possess unconscious, implicit biases predisposing them to be more harsh or lenient toward certain groups (Redfield Reference Redfield2017). To date, the study of implicit biases in judicial decision making has focused on Western judiciaries (Cohen and Yang Reference Cohen and Yang2019) where it has been shown that ideology is a strong predictor of judicial outcomes (and ideology is strongly correlated with race and ethnicity) (Harris and Sen Reference Harris and Sen2019). However, judicial decision making in these contexts is not typically characterized as strategic—that is, motivated by the expectation of material reward. Such bias is seen instead as reflecting long-standing cleavages between majority and minority groups. For example, studies of U.S. courts sometimes frame the treatment of Black defendants by white judges against the broader history of Black subjugation and white supremacy (Clarke Reference Clarke2018). Similar approaches have been used to understand majority–minority dynamics in other countries, such as Jewish–Arab interactions in Israeli courts (Grossman et al. Reference Grossman, Weinstein, Gazal-Ayal and Pimentel2016).

However, from a noninstrumental perspective, judges should be susceptible to group-based attachments and antagonisms just like ordinary citizens. In particular, implicit biases may lead judges to assign positive regard toward in-group members and negative regard toward out-group members (Oyserman et al. Reference Oyserman, Kemmelmeier, Fryberg, Brosh and Hart-Johnson2003; Paluck and Green Reference Paluck and Green2009). This kind of unconscious, affective bias may subsequently inform cognitive elements that shape how judges assign blame and responsibility (e.g., Fiske and Pavelchak Reference Fiske, Pavelchak, Sorrentino and Higgins1986) or perceive the moral character of the accused (e.g., Alicke Reference Alicke2000; Nadler and McDonnell Reference Nadler and McDonnell2012), which can in turn shape how judges interpret cases and render judgment.

Mechanisms of Bias: In-Group Favoritism or Out-Group Derogation?

The preceding discussion has highlighted how social psychological factors can shape judicial bias absent instrumental incentives. But is judicial bias a manifestation of favoritism toward members of the in-group or hostility toward members of the out-group?

Theories of social identity and self-categorization suggest that coethnic bias is likely driven by in-group favoritism (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1979; Turner and Reynolds Reference Turner, Reynolds, Brown and Gaertner2001). Self-categorization as an in-group member requires the “assimilation of the self to the in-group category prototype and enhanced similarity to other in-group members” (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis Reference Hewstone, Rubin and Willis2002). Research in this tradition also posits that individuals have a tendency to assign positive valence (such as trust, esteem, and positive regard) to members of their in-group without conscious reflection (Brewer Reference Brewer1999; Levin and Sidanius Reference Levin and Sidanius1999; Otten and Wentura Reference Otten and Wentura2001). Alternatively, it might be the case that coethnic bias is driven by out-group derogation. While group identification does not always lead to feelings of hostility toward outsiders, ample evidence suggests that such sentiments can be easily triggered in polarized societies that have a history of intergroup conflict (Stephan and Stephan Reference Stephan, Stephan and Oskamp2013). In such settings, members of the out-group are more likely to be perceived as a threat to the in-group, which can arouse feelings of fear, disgust, and thus antagonism toward the source of the threat (Sherif and Sherif Reference Sherif and Sherif1953). Whether judicial bias is driven by in-group positivity or out-group negativity generates different implications for our expectations about the affective content of written judgments, an issue we turn to in the next section.

Implicit Bias, Legal Outcomes, and Legal Writing

Recent work on judicial bias has examined specific types of stereotypes, including race and gender (e.g., Ash, Chen, and Ornaghi Reference Ash, Chen and Ornaghi2020; Rice, Rhodes, and Nteta Reference Rice, Rhodes and Nteta2019). In contrast to these approaches, our goal is to uncover the affective correlates of in-group favoritism and out-group derogation. To this end, we join a growing trend in the social sciences using text as data to trace difficult to measure concepts like sentiment and personality (Gennaro and Ash Reference Gennaro and Ash2021; Osnabrugge, Hobolt, and Rodon Reference Osnabrugge, Hobolt and Rodon2021; Ramey et al. Reference Ramey, Hollibaugh, Klingler and Hall2019).

A standard measure of judicial bias treats case outcomes as a discrete variable: whether an appeal is allowed or denied. We examine to what extent personal characteristics of the defendant (rather than legal matters of the case) affect how judges rule. However, attributing bias to either in-group or out-group attitudes is challenging if we only look at final verdicts, which lack context for understanding their motivation. That is, without a neutral control condition, we might observe that differential treatment exists, leaving unknown the motivation for that difference (Gazal-Ayal and Sulitzeanu-Kenan Reference Gazal-Ayal2010; Gill, Kagan, and Marouf Reference Gill, Kagan and Marouf2017; Harris and Sen Reference Harris and Sen2019).

However, the full text of a legal decision may provide more analytical leverage on these mechanisms. Before delivering a verdict, judges summarize each case and explain their decision’s logic. A written judgment can be conceived of as the final output of cognitive processes in which a judge uses evidence, legal concepts, and judicial discretion to support their decision (Maroney Reference Maroney2016; Rachlinski and Wistrich Reference Rachlinski and Wistrich2017; Simon Reference Simon1998).Footnote 4 Our research builds on a robust literature examining how affective framing and cues shape legal reasoning and outcomes (Beattey, Matsuura, and Jeglic Reference Beattey, Matsuura and Jeglic2014; Black et al. Reference Black, Treul, Johnson and Goldman2011; Liu and Li Reference Liu and Li2019; Wistrich, Rachlinski, and Guthrie Reference Wistrich, Rachlinski and Guthrie2015). Using this lens, we posit that if judges are indeed making decisions based on their implicit biases, such sentiments are likely reflected in their written legal judgments.

To dissect judgments for evidence of in-group versus out-group bias, we first identify what kinds of affective content we would expect to see if either mechanism were in play. Existing research finds in-group favoritism to be strongly associated with notions of trust; in the African context, such studies tend to portray trust as a basic behavioral regularity in coethnic interactions (e.g., Arriola, Choi, and Gichohi Reference Arriola, Choi and Gichohi2021; Robinson Reference Robinson2020). Social psychology research similarly argues that trust underpins in-group favoritism (Allport Reference Allport1954; Brewer Reference Brewer1999), whereas disgust more often accompanies feelings of out-group derogation (Hodson et al. Reference Hodson, Choma, Boisvert, Hafer, MacInnis and Costello2013; Mackie, Devos, and Smith Reference Mackie, Devos and Smith2000). From these findings, it is reasonable to expect that the presence of trust-related and disgust-related language in appeals judgments would imply biases suggesting in-group favoritism and out-group derogation, respectively.Footnote 5

Are Certain Groups More Predisposed to Bias?

Our main claim is that psychological mechanisms can predispose judges to demonstrate group-based bias in judicial decision making. However, this does not necessarily mean that judges of different groups are equally susceptible to such biases. Literature in social psychology and sociology suggest that prevalence of biases among groups corresponds to hierarchical status (e.g., Hagendoorn Reference Hagendoorn1995; Mullen, Brown, and Smith Reference Mullen, Brown and Smith1992). Two prominent theoretical strains are social identity and dominance theories and realistic group conflict theory.

Research on social identity theory and social dominance orientation predicts that processes of social comparison and social identification may lead members of higher-status groups to be more likely to discriminate between the in-group and out-group(s) (Sidanius et al. Reference Sidanius, Levin, Liu and Pratto2000; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1979). “Dominant” groups derive esteem from their superior status, reinforcing the value and worth they attach to their dominant position (Sachdev and Bourhis Reference Sachdev and Bourhis1987). Being at the top of the social hierarchy makes such groups more predisposed to preserving the status quo as a means of sustaining their privileged access to resources and power (Harkness Reference Harkness2018; Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto2001). Evidence reveals higher levels of in-group bias among dominant group members in hierarchical societies in contexts as diverse as Israel, India, the Netherlands, Northern Ireland, and the United States (Levin Reference Levin2004; Levin and Sidanius Reference Levin and Sidanius1999).Footnote 6

In the Kenyan case, this framework implies that bias should be concentrated among judges belonging to the “dominant” ethnic group: the Kikuyu. As the numerically largest ethnic group in Kenya, Kikuyus have seen their leaders occupy the presidency three times (Jomo Kenyatta, Mwai Kibaki, and Uhuru Kenyatta), comprising most of the postindependence period. Their political dominance has spread to other branches of government, including the judiciary, with multiple Kikuyu jurists serving as Chief Justice.Footnote 7

By contrast, realistic group conflict theory in social psychology and political science argue that bias and discrimination mirror political conflicts among competing groups (Horowitz Reference Horowitz2000; Sambanis and Shayo Reference Sambanis and Shayo2013; Sherif and Sherif Reference Sherif and Sherif1953); intergroup animosity is rooted in competition over scarce resources (Gurr Reference Gurr2015). Out-group discrimination and conflict thus reflect existing grievances over the distribution of material goods (Sherif Reference Sherif1988). Other work in this tradition contends that intergroup cleavages result from the subordination of certain groups, entrenching intergroup animosity and systems of marginalization and exclusion (Wimmer, Cederman, and Min Reference Wimmer, Cederman and Min2009).

In the Kenyan context, this second perspective would lead us to expect bias to arise between specific constellations of ethnic groups. The Kikuyu and Kalenjin ethnic groups have long monopolized political power and engendered grievances among excluded groups, notably the Luo (Widner Reference Widner1992). The Kikuyu–Luo rivalry stems from the early independence struggle for national control between Kikuyu President Jomo Kenyatta and Luo Vice President Oginga Odinga.Footnote 8 Kalenjin–Luo relations have also been strained for decades, reflecting similar national-level power struggles.Footnote 9 More recently, Kikuyu–Kalenjin hostilities have intensified since the return to multiparty politics in the 1990s, culminating in the infamous postelection violence of 2007–08 that led to more than 1,000 dead and more than 600,000 displaced (Lynch Reference Lynch2014). Given Kenya’s long history of ethnic rivalries at every level of government from the presidency downward, these tensions might be on display in the courtroom.

Observable Implications

The preceding discussion suggests three observable implications. First, we expect that judges will exhibit identity-based implicit bias in their decisions, even absent strategic or instrumental considerations. Second, these biases may align with coethnicity and be driven by in-group favoritism; alternatively, out-group derogation may drive negative cross-ethnic biases. Patterns of trust- or disgust-related language in written judgments should thus mirror in-group or out-group motivated biases. Third, such biases might be higher among judges who belong to the dominant ethnic group; alternatively, bias may follow historical patterns of cross-ethnic rivalry.

Context: Judicial Outcomes in Kenya and Africa

In contrast to US courts, with distinct federal- and state-level jurisdictions, Kenya’s unitary judiciary organizes courts nationwide. We focus on criminal appeals in Kenya’s Judiciary, which originate in Kenya’s lowest-level magistrate courts and would be analogous to local or county-level courts in the US. However, while US state courts abide by different laws depending on the locality, each of Kenyan high courts is governed by the same set of rules and procedures. To seek redress from lower court judgements, a defendant may appeal to the High Court, the next level in Kenya’s judicial hierarchy.Footnote 10

Appeals decisions are a difficult test for theories of identity-based bias due to the incentive structures confronting judges who hear appellate cases. In particular, high court decisions are made publicly available online through Kenya’s National Council on Law Reporting. This transparency is partly intended to inform precedent-based judicial decision making across the country, but publicizing such information incentivizes judges to mitigate any indication of bias in their legal reasoning. Furthermore, due to their higher status in the judiciary, high court judges generally have less anonymity than lower-level magistrates, wherein greater public recognition underscores the need to maintain at least the appearance of impartiality.

To date, little academic work focuses on judicial outcomes in lower courts in Kenya, or Africa more broadly.Footnote 11 The focus instead has been on superior court politics. For example, Widner’s (Reference Widner2001) study of courts in postcolonial Africa examines the development of judicial independence at the upper echelons of the judiciary, centering on the storied career of Francis Nyalali, Chief Justice of Tanzania. Other works in this field have also focused on the mindsets of High or Supreme Court justices, including Gloppen and Kanyongolo’s (Reference Gloppen and Kanyongolo2007) analysis of the High Court and the Supreme Court of Appeal in Malawi, VonDoepp’s (Reference VonDoepp2006) comparative study of the High Courts of Malawi and Zambia, and Vondoepp and Ellett’s (Reference Vondoepp and Ellett2011) comparative analysis of executive–judicial relations in five Commonwealth African countries.

The understandable focus on superior courts among scholars of African judiciaries has helped illuminate elite-level decision making, particularly questions of constitutional jurisprudence or judicial review, but these approaches highlight an unavoidable challenge to studying superior courts across the region: although politically salient, high-profile cases are relatively infrequent, making the relationship between legal output and judicial identity difficult to assess systematically.Footnote 12 Furthermore, the number of superior court justices is small, making inference difficult.Footnote 13 To understand the influence of ethnic identity on more quotidian legal outcomes, more detailed data on case outcomes is required.

Data and Methods

We focus on two elements of appeals case outcomes: whether or not an appeal succeeds and the presence of trust- and disgust-related language relating to in-group favoritism and out-group derogation. For both analyses, we rely on a corpus of appeals from the Kenya Law Cases Database, an online repository of court rulings maintained by the National Council for Law Reporting (Kenya Law). We downloaded 9,545 criminal appeals rulings issued by the High Court between January 1, 2003, and December 31, 2017. Each ruling contained the full text of the judgment, including the nature of the alleged crime, the original sentence, the date of the ruling, and the county court wherein the case was heard. Using regular expressions, we created a set of case-level variables for analysis.

To classify our main dependent variable—whether the appeal was allowed or denied—we relied on regular expressions as well as a hand-coded classification scheme. Hand coding was necessary because judicial writing style varies by judge, especially with respect to their judicial logic. Wherever regular expressions could not fully capture the idiosyncracies of legal reasoning, we relied on human coders to complete our classification of appeal outcomes.

To construct the main independent variable, we collected data on the ethnicity of judges and appellants. We used appellants’ names to measure ethnicity, an increasingly common approach in political science (Enos Reference Enos2016; Harris Reference Harris2015; Hassan Reference Hassan2017). Our procedure leveraged information from Kenya’s voter register, which identifies voter names from ethnically homogeneous areas. We created a dictionary-based ethnicity classifier to estimate the probability of ethnicity for a given last name, thereby linking each of nearly 10,000 persons’ names to an ethnic group. Given the limited number of judges in the data, a member of the Kenyan legal community resolved ambiguous classifications of judge ethnicity by canvassing professional networks.Footnote 14 , Footnote 15 , Footnote 16

Measuring Sentiment in Legal Judgments

We expect in-group favoritism or out-group derogation to motivate bias when judges evaluate an appeal. To test this, we use text-as-data approaches to assess the degree to which emotive reasoning appears in judicial writing. Our analysis builds on conventional dictionary methods wherein the count or proportion of key words in a given document is used to determine that document’s category (Grimmer and Stewart Reference Grimmer and Stewart2013). To this end, we generated word lists capturing our main mechanisms of interest: in-group favoritism or out-group derogation. Specifically, we identified terms related to trust and disgust to measure in-group favoritism and out-group derogation in written legal decisions.Footnote 17 We then calculated the number of trust and disgust terms as a proportion of total terms for each decision.Footnote 18

The technical nature of judicial writing makes this approach a challenging test of our proposition. Not surprisingly, official guidelines from the Kenya Criminal Procedure Benchbook explicitly discourage judges from invoking emotive sentiments in their decisions to avoid allegations of bias: “judgment should not contain derogatory language … a dispassionate approach and clear finding of fact, are more indicative of judicial approach, and do not lay the magistrate open to a charge of possible bias. The court may express strong condemnation of the conduct of the accused, but it must be careful not to be abusive or, for example, imply that the conduct is what might be expected of those belonging to a particular race, religion, etc.”Footnote 19

Although these rules are considered standard practice, the inclusion of explicit instructions suggests a broader concern among legal practitioners in Kenya—that judges may indeed be discriminatory in their legal opinions and need to guard against such tendencies when rendering verdicts. Given these cautions, we expect that any expression of emotion in a written judgment will likely reflect subtle, implicit, and often unconscious biases rather than overt prejudice.

Examples from our appeals corpus corroborate these expectations, suggesting that terms of trust and disgust are subtly expressed in legal writing. In one successful appeal, the judge described the appellant’s standing using terms of trust, remarking that the “magistrate erred in law and fact in disregarding the appellant’s defence, which was consistent and trustworthy[.]”Footnote 20

In another ultimately denied judgment, the judge invoked terms of disgust in assessing the facts of the case: “the appellant had converted [the witness] into his wife, a shameful act indeed. She also physically suffered by the damage of her womanhood. The best description that this court can accord to the behavior of the appellant was that he was a beast to [the witness]. As rightly noted by the trial magistrate, he ought to be kept away from the society.”Footnote 21 Terms of disgust written into judgments reveal a judge’s personal and moral assessments of appellant character: “the offence committed was barbaric, immoral and had definitely left the complainant traumatized. I find that was a justification for passing sentence higher than the minimum provided and did not in any way offend the provisions of … the Constitution of Kenya[.]”Footnote 22

These excerpts illustrate that trust and disgust dictionaries capture personal evaluations of appellants, distinct from an appeal’s legal merits. Given the technicality of legal writing, including the instruction to minimize perceptions of bias in the record, our approach is a hard test of the hypothesis that judicial bias is motivated by in-group favoritism or out-group derogation. If we find evidence that judges invoke terms of trust (disgust) with respect to coethnic (non-coethnic) appellants, we take it as consistent with the posited affective-cognitive mechanisms that may influence outcomes.

Research Design

To identify the effect of identity on criminal appellate judgments, we exploit features of the case assignment process in the Kenyan Courts. Cases arriving on the docket of each high court station are sorted into categories for assignment to legal divisions within the court station: family, commercial and admiralty, constitutional, land and environment, and, most relevant for our purposes, criminal. The deputy registrar, responsible for case scheduling, assigns each new incoming case to a judge. This intradivision assignment is determined by judges’ calendars and existing workloads, not by case characteristics: case assignment criteria—a judge’s schedule and case load—are orthogonal to case particulars like the ethnicity of defendants and judges. This provides us with quasi-random variation in the ethnic relationship between the appellant and the judge.

We use a linear model to examine the relationship between coethnicity and case outcomes:

where Yi is either the binary indicator for whether the appellate judge ruled in favor of the defendant or a measure of sentiment in text; Mi takes the value of one if the case was assigned to a coethnic judge of the defendant; and Xc is a vector of controls and fixed effects including courthouse-year, judge ethnicity, individual judge, and in our most restrictive specification, courthouse-year and individual judge fixed effects. We present our baseline results with our coethnic match variable and courthouse-year fixed effects and progressively add more restrictive sets of fixed effects and controls. Then, we conduct ethnic subgroup analyses by judge ethnicity to probe for differential bias.

Case allocation is a manual process, and it is possible that the principles of case assignments are not respected. Appendix Table B1 provides balance checks suggesting that the case assignment mechanism likely induced quasi-random variation in judge–defendant coethnicity. Conditional on the courthouse-year in which the case was heard, there is balance on most covariates. Most differences remain insignificant, except for the proportion of crimes classified as murder, manslaughter, or theft. Given this, we include regression specifications with these covariates, which do not alter our findings.

Findings

Do Kenyan appellate judges show identity-based bias in their decision making? Table 1 summarizes the main results of the linear probability models where the outcome is equal to one if the judge ruled in the defendant’s favor, zero otherwise. Our main focus is the coethnic match covariate, which is equal to one when the judge and the defendant share the same ethnic identity.

Table 1. Effect of Coethnic Match between Appellant and Judge

Note: Coefficients estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS). “Coethnic match” is a binary variable equal to one if the judge and appellant share the same ethnic group, zero otherwise. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

The results indicate that Kenyan judges favor coethnic appellants. The basic specification without fixed effects in column (1) shows that judges are 4.2 percentage points more likely to decide in favor of a coethnic over a non-coethnic defendant. Columns (2) through (6) provide increasingly stringent empirical tests by adding fixed effects to account for factors that vary by location and time (i.e., courthouse-year) and judge, as well as case-specific controls describing the offense in question. Although the magnitude of the bias fluctuates marginally with the addition of these fixed effects, the findings remain robust.Footnote 23

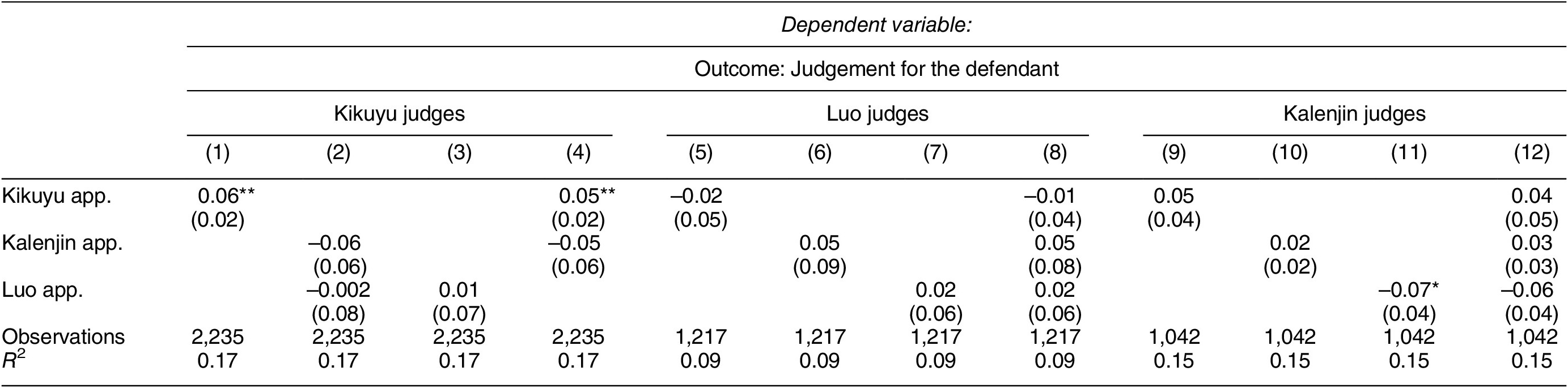

In the theory section, we generated two contrasting predictions regarding heterogeneity in coethnic bias across judges belonging to different ethnic groups. We test these predictions by running a series of subgroup analyses, reported in Table 2 and Table 3. The social dominance/identity perspective, which predicts that dominant or high-status groups exhibit more in-group bias, finds strong support in Table 2; coethnic bias is observed primarily in decisions handed down by Kikuyu judges and, to a lesser extent, Kamba judges.Footnote 24 The Kikuyu ethnic group has occupied both the presidency and the position of chief justice for a significant portion of the postindependence period, including during the span of our analysis, and can thus be considered a “dominant” ethnic group in Kenya’s political, economic, and legal landscape.

Table 2. Effect of Coethnic Match between Appellant and Judge, by Judge Ethnicity

Note: Coefficients estimated using OLS. “Coethnic match” is a binary variable equal to one if the judge and appellant share the same ethnic group, zero otherwise. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Table 3. Dyad-Specific Effects between Appellant and Judge

Note: Coefficients estimated using OLS. All models contain Courthouse-year FE, Judge FE, and case-specific controls. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

Given these findings, we urge caution in interpreting the Kamba estimate in Table 2 as robust (especially considering that the direction of the estimated relationship is unstable).

Our findings suggest that judges of politically dominant ethnic groups deliver more favorable outcomes to appellants of the same ethnicity. But to what extent are such judges explicitly discriminating against members of the political out-group? Recall that if the political rivalry hypothesis were true, we would expect to see appeals outcomes vary depending on whether judges and appellants come from groups with a history of interethnic conflict; in particular, judges should rule more harshly against appellants from politically rivalrous groups. In Table 3, we examine the decision-making patterns of judges belonging to three large and politically significant ethnic groups in Kenya— the Kikuyu, Kalenjin, and Luo—that have recently experienced divisive contests for control of the state, including violent conflicts over the outcomes of national elections. The results provide limited support for the idea that bias against out-groups follows the logic of political rivalry and conflict. Although we see a marginally significant effect on Luo appellants for Kalenjin judges, this finding dissipates when indicators for Kikuyu and Kalenjin appellants are included in the regression. Our findings thus suggest that the Kikuyu, Kalenjin, and Luo judges do not systematically penalize appellants from rival ethnic groups.

In the Online Appendix, we present robustness tests related to Tables 1 and 2. Appendix D.1 and D.2 replicates the main results using inverse probability weighting to account for unit-level differences in treatment probability and to exclude observations that had no chance at randomization (e.g., Kamba appellants in court stations staffed exclusively by Kamba judges or, alternatively, Kamba appellants who had no chance of being assigned to a Kamba judge). Despite this loss of power due to a smaller sample size, the models recover similar point estimates and, for the more reasonable weighting specifications, retain statistical significance. Appendix D.3 applies the same IPW approach to the findings reported in Table 2 to similarly recover point estimates for Kikuyu judges that are statistically significant and similar in magnitude for the more reasonable weighting specifications. Kamba judges also show positive and significant results in Table 2. However, the IPW estimates for Kamba judges in Appendix D.3 lose significance, switch signs, and attenuate in the more reasonable weighting specifications. Given this, we do not consider these estimates to be robust and put little weight on the Kamba judge estimates. Appendix D.7 incorporates uncertainty over appellants’ ethnicity classification, given our probabilistic name-based approach, showing the full distribution of estimates over 10,000 iterations, for column 6 of Table 1 and each ethnic group in Table 2, both with and without inverse probability weights. Again, the results comport with the main results. Appendix D.6 reruns the results above, aggregating ethnic groups commonly associated with one another, finding little change in the results.Footnote 25

Identifying Mechanisms of Coethnic Bias: Favoritism or Derogation?

To elucidate whether in-group favoritism or out-group derogation drives coethnic bias in judicial decision making, we examine the texts of appeals judgments. We calculate the proportion of trust, disgust, positive, and negative sentiments for each written judgment using word embeddings. We estimate the effect of coethnicity using OLS as described in Equation 1 above.

Table 4 shows that only trust has a positive and significant relationship with the coethnic match variable. Judgments for coethnics contain approximately 0.12 standard deviations more trust-related words than judgments written for non-coethnics. A judge invokes terms of confidence, credibility, and honesty more often when writing a judgment for a coethnic. The insignificance for the disgust score suggests that judges use similar amounts of disgust-related language when writing for coethnics and non-coethnics. We interpret this as evidence that judicial bias is a manifestation of in-group favoritism rather than out-group derogation.

Table 4. Coethnic Bias in Written Judgments: Corpus Seeds, GloVe Vectors

Note: Coefficients estimated using OLS. “Coethnic match” is a binary variable equal to one if the judge and appellant share the same ethnic group, zero otherwise. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01.

We draw two main conclusions from this dictionary analysis, both of which should be interpreted with caution. First, despite the fact that judges are explicitly instructed to refrain from issuing decisions based on nonlegal considerations, they are still likely to invoke emotive sentiments (trust) when regarding coethnic appellants. This has important implications for legal reform efforts in Kenya, the bulk of which have either implicitly or explicitly assumed that judicial bias falls along gender, income, or other socioeconomic dimensions. Our findings suggest that more consideration should be directed instead toward the conscious or subconscious favoritism judges may harbor for coethnics. Second, our analysis reveals the utility of text-as-data approaches on judicial writing, especially the applicability of minimally supervised dictionary methods on niche corpora. Our main findings suggest that conventional dictionary methods combined with word embedding models elucidate different sources of implicit, affective bias in legal language and help assess the weight of one type of bias against another.Footnote 26 Although these findings are more suggestive than definitive, they provide a framework for understanding some nuances of judicial decision making.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this paper is the first detailed analysis of the relationship between ethnic identity and legal outcomes in an African context. We provide evidence of a coethnic bonus in appeals decisions using a new dataset of almost 10,000 criminal cases from the Kenyan High Court. We find that, when faced with a coethnic appellant, a judge is about 3 to 5 percentage points more likely to grant the appeal. These effects are concentrated among ethnic Kikuyu—the “dominant” ethnic group in both the political and judicial arena—where the coethnic bonus is around 6 to 10 percentage points. Judgments written for coethnics also show higher concentrations of trust-related words—an indicator of in-group favoritism. We find little evidence in written judgments of out-group derogation (i.e., words related to disgust). These findings echo the observation of US-based legal practitioners that “ingroup and outgroup are differentiated more as targets of positive than of negative feelings” (Greenwald and Pettigrew Reference Greenwald and Pettigrew2017, 161).

How does the magnitude of our results relate to similar work on judiciaries in other contexts? While the magnitude of the effects we discover fall within the range of ethnic bias observed in other studies, it is important to note that it is moderate in comparison with work on criminal appeals outcomes in Israel and the US, suggesting that the guidelines set by the Kenyan Criminal Procedure Judicial Benchbook judiciary to guard against judicial bias may be effective to some extent.Footnote 27 , Footnote 28

These results have important implications for the internal governance of the judicial branch. In particular, we provide evidence that in-group favoritism may privilege some defendants’ appeals over others. In such circumstances, the composition of the local judiciary and the geographic reach of the judicial services may determine how frequently this type of bias might occur. While shuffling judicial appointments to different court stations can help encourage impartiality to a certain extent, our findings suggest that more fundamental factors such as identity can still affect legal outcomes. The results presented here thus suggest that future Kenyan reform efforts with respect to judicial vetting and legal training processes might pay greater attention to the potential for bias in judicial decision making.

Our findings also complement existing research on the political drivers of judicial outcomes. Much of this work assumes that judges are strategic actors who often must navigate uncertain terrain in order to ensure their own political survival (Helmke Reference Helmke2002). Such strategies can be especially important in autocratic or weakly democratic regimes where leaders have greater wherewithal to manipulate courts to further their political agenda or hold onto power (Shen-Bayh Reference Shen-Bayh2018). Much like the broader literature on African courts, these studies tend to focus on high-profile cases relating to constitutional or national security questions (Ginsburg Reference Ginsburg2003). Our study expands this literature by shifting attention to lower-level courts: institutions that not only hear lower-visibility cases much more frequently but also are often the only judicial institutions directly interacting with regular citizens.Footnote 29

Perhaps more crucially, our analysis suggests that judicial bias in a multiethnic society such as Kenya is primarily concentrated among judges from the “socially dominant” group. This finding has theoretical and practical implications for how we understand implicit bias in both the legal domain and beyond. Theoretically, it urges us to revise our models of implicit bias and pay greater attention to how contextual variation in group status and hierarchies across societies can condition bias. That is, rather than assume that implicit bias is an inherent feature of group identity (and one that manifests evenly across all groups), such bias is potentially heterogeneous and may vary depending on which groups have historically exercised sociopolitical and economic dominance over others. This is not to say that socially nondominant groups do not hold psychological predispositions toward in-group or out-group members or that they are not susceptible to bias per se. But the fact that their biases are not directly observed in the legal decision-making process should prompt future investigations as to why this is the case.

Practically, rethinking implicit bias along these terms means also revisiting the design of policy interventions intending to bring fairness and impartiality to judicial decision making. Prior scholarship has shown that diversifying the bench can help reduce judicial discrimination against members of minority groups.Footnote 30 These works show that in societies dominated by a single ethnic group, improving diversity on the bench increases the frequency and intensity of “contact” between members of the dominant group and out-group, which may help reduce implicit biases among dominant group judges in the medium to long term. However, it remains unclear whether diversifying the bench in more ethnically diverse societies (where multiple groups have either dominated government or shared political control) will have the same mitigating effect on implicit bias in judicial decision making. In particular, policies that are meant to increase representation of nondominant ethnic groups on the bench may not in and of themselves be sufficient in reducing judicial bias unless there is also change in the overarching power relations among groups.

Our findings also suggest that policy interventions that are designed to reduce implicit bias in the courts should be attuned to heterogeneity that manifests as a result of status or power structures and hierarchies. That is, if judges from socially dominant groups are more susceptible to biases, interventions that attempt to reduce the prejudices that dominant group judges hold toward minority defendants and appellants may be one of the most effective means through which discrimination can be curbed in the judicial realm (e.g., Redfield Reference Redfield2017, chaps. 11 and 12).

There are important scope considerations to our findings. In particular, our analysis focuses on bias at the appeals stage rather than courts of first instance. This means that we do not account for whether the identity of lower court magistrates affects judicial decision making during the initial trial or whether magistrate ethnicity shapes the opinions of higher court justices upon appeal. It is possible that coethnicity plays a similar biasing role at the magistrates level, which may in turn affect the likelihood of appeals success at higher courts (e.g., Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2014; Sen Reference Sen2015).Footnote 31 We leave it to future studies to examine these dynamics in greater detail.

Given the relative infancy of studies of bias in legal decision making in African contexts, there is ample opportunity to build upon our findings and contribute to existing debates on these themes in other geographic contexts. We see three particularly promising areas for future research. First, what are the building blocks of bias? Building on work like Liu and Li (Reference Liu and Li2019) and Wistrich, Rachlinski, and Guthrie (Reference Wistrich, Rachlinski and Guthrie2015), future studies may choose to experimentally manipulate characteristics of hypothetical cases in order to better understand how identity-based, moral, and emotional factors shape judicial decision making in the Global South. Second, another promising line of research might explore techniques for bias reduction such as simple informational interventions that create awareness about bias and may aid in its reduction (Liu Reference Liu2018; Redfield Reference Redfield2017). Third, do resource constraints exacerbate bias? Due to lack of infrastructure and operating funds, judicial officers in lower-income countries are often overworked and underresourced.Footnote 32 Given the implicit, heuristic nature of in-group biases, it seems reasonable to conclude that excessive workloads may exacerbate bias by forcing judges to produce judgments quickly as opposed to spending the time necessary to deliver circumspect, carefully reasoned judgements. To the extent that such constraints can be addressed, examining the logistical burdens of judicial decision making may help elucidate whether and how institutional reforms can enhance due process.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S000305542100143X.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JCSOB8.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Zeinab Abbas, Laboni Bayen, Shehryar Hanif, Soohyun Hwangbo, Cindy Koyier, Fanisi Mbozi, Kaelin Miller, Khoi Ngo, Morgan Tompkins, and Cornelius Wekesa Lupao for excellent research assistance. Comments from Leonardo Arriola, Sarah Brierley, Asli Cansunar, Gidon Cohen, Justine Davis, Andrew Eggers, Aaron Erlich, Matthew Gichohi, Siri Gloppen, Robin Harding, Mai Hassan, Nahomi Ichino, Patrick Kuhn, Harrison Mbori, Susanne Mueller, Noah Nathan, George Ofosu, Cristian Pop-Eleches, Georg Picot, Pia Raffler, Lise Rakner, Pedro Rodriguez, Nelson Ruiz, Meshack Simati, Arthur Spirling, Peter Van der Windt, Neil Visalvanich, Nick Vivyan, Zach Warner, and Stephane Wolton have significantly improved this manuscript. The work also benefited from excellent comments during presentations at the University of Bergen, the London School of Economics and Political Science, the University of Oxford, Durham University, Trinity College Dublin, the Global Law and Politics Workshop, and the MIT Political Behavior Workshop. The authors contributed equally to this project. Their names are listed alphabetically.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.