Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: United Politics—Divided Culture?

- Part I What Remains: History and the Constitution

- Part II What and How Do We Remember? Literature, Film, and Exhibitions

- Part III A Changing Reception: Painting, Orchestras, and Theaters

- Part IV A Virtual Wall? Education and Society

- Epilogue: The Wende and the End of “the German Problem”

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Epilogue: The Wende and the End of “the German Problem”

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 August 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: United Politics—Divided Culture?

- Part I What Remains: History and the Constitution

- Part II What and How Do We Remember? Literature, Film, and Exhibitions

- Part III A Changing Reception: Painting, Orchestras, and Theaters

- Part IV A Virtual Wall? Education and Society

- Epilogue: The Wende and the End of “the German Problem”

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

WHAT TURNED WITH THE WENDE and how much? And how much remained? The essays in this volume, speaking from the vantage point of an array of disciplines, represent highly varied attempts to answer that question. This chapter is an economic and political historian's response, an argument that the Wende highlighted and completed a profound transformation in Germany's international role during the second half of the twentieth century, with results that are likely to prove both lasting and beneficial.

A “German Problem” No More?

For much of the period between 1848, at the latest, and 1989, something called “the German Problem” constituted a consistently ominous and periodically destructive flashpoint of European politics. What the problem actually was, however, varied over time. In its earliest and final phases, the problem emerged from the country's division and the tensions aroused by desires to either overcome or maintain that condition. In the long middle interval between 1871 and 1945, the problem stemmed from the opposite situation, namely the concentrated power and ambition of a single state that called itself throughout the period, despite three distinct governing systems (monarchy, republic, and dictatorship), simply das Deutsche Reich, the German Empire. But whether born of division or unity, the chief consequence of the German Problem always seemed the same: war. That was the upshot in 1864, 1866, 1871, 1914, and 1939. It also was very nearly the result in 1875, 1906, 1911, 1936, 1938, 1958, and 1961. Some highly placed people, notably Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher of Great Britain, thought that war would be the consequence of the Wende, too.

Why were they wrong? Why do contemporary laypeople and scholars have no use for or comprehension of the phrase “the German Problem”? Why did 1989 mark the end of an epoch—though, of course, not “the end of history” that Francis Fukuyama (1992) rather foolishly proclaimed? To answer these questions, one has to begin with a sense of what conditions gave rise to the German Problem. Identifying them has been one of the central preoccupations of historical writing on Germany since the dawn of the twentieth century. As a result, there is no shortage of explanations of what made Germany so explosive and disruptive a country for almost 150 years. Oversimplifying somewhat, I boil these accounts down into four broad groups.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

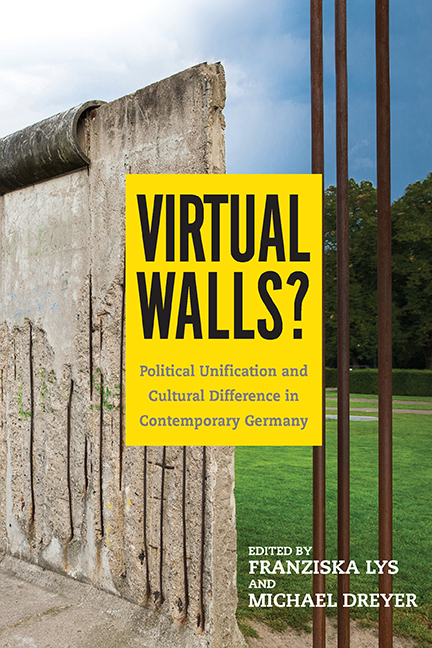

- Virtual Walls?Political Unification and Cultural Difference in Contemporary Germany, pp. 183 - 190Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017