In 1549, the celebrated Paduan physician Giambattista da Monte treated the Earl of Montfort for a case of hypochondriacal melancholy. Nowadays, the term ‘hypochondria’ refers to an excessive anxiety that one has a serious medical condition. But in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, it had a different meaning: hypochondriacal melancholy was of a specific type that was located in the hypochondriac region, the middle region of the body just below the midriff, where the liver, spleen, and gallbladder reside. In Renaissance physiology, these organs comprise the central system both for producing the humours and for refining them from the nutrition that the body takes in. In the Earl of Montfort’s case, his belly was too cold while his liver was too hot. He was suffering from pustules and ulcers. He had indigestion and bad wind. And he was experiencing the gloom and sadness which are the typical accompaniments of melancholic disease.

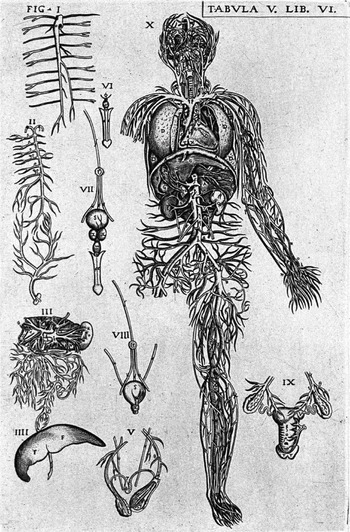

Figure 2.1 The venous and arterial system of the human body with internal organs and detail figures of the generative system. Engraving (1568).

This illustrious patient suffered from a chronic condition that revealed itself as much in the body as in the mind, and his doctor treated him accordingly. Da Monte’s aim in treatment was both to restore his body to health and to quieten his spirits, prompting him towards contentment and tranquillity. Therefore he advised his patient to leave the royal court and all the troubles, jealousies, ambition, and politicking that went along with it. He should avoid eating pork and fish; he should drink white wine; he should live in a pleasant house with good air (conveniently, the Montfort family’s ancestral home lies on the north shore of Lake Constance). He should refrain from sex, though since the patient was not keen on the idea of total abstinence, the doctor compromised and asked him to moderate his sexual activity – and never on a full stomach. The doctor also devised a purge, with ingredients including flowers from the golden shower tree (an ancient purgative remedy in Eastern and Western medicine), rhubarb, and spices.1

Thus Giambattista da Monte treated his patient for complex disorder of body, mind, and spirit with therapies that responded to the same. The case of the Earl of Montfort is one that Robert Burton refers to a number of times in the Anatomy and reveals how closely and intricately Renaissance physicians thought that the body and mind worked together. On the one hand, emotional disturbances could cause bodily illnesses. On the other, bodily diseases could ‘affect the soul by consent’ (i.374). Burton mentions cases where patients degenerated into melancholy states after contracting an ague, or plague, or syphilis, or epilepsy. And likewise, mental disturbance could often lead to physical sickness.

In this chapter we shall explore the variety of ways in which body and mind interact in Renaissance melancholy. These days, we commonly describe physical ailments that have psychological origins as psychomatic, a word that combines the Greek words for mind or spirit – psyche – and body. The word is a nineteenth-century coinage – the Oxford English Dictionary finds its first usage in Samuel Taylor Coleridge – and has only been used in a medical context since the early twentieth century.2 Yet the ancient Galenic medical tradition that Giambattista da Monte, Robert Burton, and their contemporaries followed provided a highly sophisticated understanding of how physical and mental health were intertwined, and of how one could affect the other. It was not only obvious to them, but also thoroughly logical according to medical theory, that a stomach complaint could cause a chronic low mood or that long-term sadness could break out in a skin rash. As we have seen, the Earl of Montfort’s hypochondriacal melancholy had physical features as well as mental ones; indigestion, headaches, and vertigo were all recognised symptoms of the disease.

Burton uses a musical image to explain how the body works upon the mind: ‘as a lute out of tune; if one string or one organ be distempered, all the rest miscarry’ (i.375), so something wrong in one part of the body can affect the whole person. ‘Distemperature’ is a term commonly used in Renaissance medical writing which points to the heart of theories about the self. If the string of a musical instrument is distempered, it has slid out of tune. If a body or a part of the body is distempered, it has lost its fundamental balance: the perfect combination of cold, heat, moisture, and dryness that it needs to function properly.

What we nowadays mean by bodily temperature – in other words, how hot or cold it is – is only one element of the Renaissance idea of temperature: how well ordered or otherwise the body and mind are, and how the humours combine to contribute towards a person’s distinctive features, personal character, and overall disposition. Renaissance selfhood and emotional experience are far more than simple products of the humoral body; nonetheless, their constructions are underpinned by a sophisticated and complex theory of the interrelationship of body and mind.3 The Earl of Montfort’s anxious and downcast state of mind was not simply the result of humoral imbalance and intestinal gas. It was also caused by the mental strain of life at court, and the therapies da Monte prescribed took account of this. We shall consider first the matter of melancholy itself and how it could be inherited; then some Renaissance ideas about how melancholy appeared in the visible features of sufferers; and we will explore the multiple varieties of melancholic disease that could be produced by ‘adustion’ or corruption of the humours. Finally, we will turn to the colour of black bile as it reveals itself not only in individuals, but nations and peoples.

The Matter of Melancholy

Everyone has melancholy within them, but not everyone suffers from it: that is the classical humoral theory upon which Burton’s understanding of the disease depends. The four humours are fluids in the body which each have different qualities and which work together to support life. We know what some of them look like, most obviously blood: the hot, moist humour that nourishes and strengthens the body. Blood performs the role of keeping different parts of the body in communication with one another through the veins and arteries (see Figure 2.1) because it is a channel for the spirits: vapours that are the instruments of the soul and which form ‘a common tie or medium between the body and the soul’ (i.148). Phlegm, likewise, is sometimes visible. The cold and moist humour, its job is both to nourish the body and to keep the moving parts lubricated, such as the tongue through saliva. The other two, dry humours are more hidden within the body. Choler or yellow bile, hot and dry, helps to preserve the natural heat of the body, aid the senses, and to expel excrements. Finally there is melancholy or black bile, ‘cold and dry, thick, black, and sour … a bridle to the other two hot humours, blood and choler, preserving them in the blood, and nourishing the bones’ (i.148). We do not normally see melancholy as we would phlegm, but its presence might be detected in a blackened stool or dark-coloured blood.

The humours maintain a careful balancing act to regulate the body’s temperature and to offset one another. Galen taught that there are three states of life: there is health, sickness, and a medium, neutral state between these two contraries. Most people fall into the middle category, and very few can be deemed fully healthy. As Burton’s contemporary John Donne puts it in his poem The First Anniversary:

A neutral state of health simply means an absence of sickness, while in that elusive, ideally healthy body, the humours work in perfect harmony with one another.

The humours have several correspondences. The inner workings of the human body are a miniature form of the whole cosmos, and the four humours are linked to the four elements: blood and air, phlegm and water, choler and fire, melancholy and earth. So the whole world mirrors what is going on within a single human being, and vice versa. The humours also correspond to the phases of human life, and this explains one facet of why not only our bodies but our attitudes and behaviour change as we get older. Young people abound in natural heat. As a result they are prone to choler or hot-headedness, easily losing their temper; they are energetic and more prone to lust and sensuosity. Healthy young people have colourful cheeks, a sign of a sanguine temperament (where blood predominates). With age, the body’s finite stores of what is known as the humidum radicale – radical moisture – become depleted. The humidum radicale is the vital force that gives us energy. We naturally lose it as we get older, but our habits may use it up it faster. Frequent sex, drunkenness, anything that causes us to perspire all heat the body and expend moisture, of which the body only has a limited amount. This is one reason why the Earl of Montfort was instructed to moderate (if he could not abstain from) his sexual activity. Illness depletes the humidum radicale too, fevers in particular because they cause sweats and frequent changes in the body’s temperature.

As people get older, their heat and moisture diminish and hence their humoral dispositions become drier and colder. According to Renaissance medical theory, this is evident in the fact that old people are wrinkly. And as an inevitable result of this drying and cooling process, the humour black bile is ‘superabundant’ in them. The common accompaniments of old age – physical inaction and weakness, loneliness, aches and pains, griefs – are part and parcel of the melancholy state:

After seventy years (as the Psalmist saith [Psalms 90:10]) “all is trouble and sorrow”; and common experience confirms the truth of it in weak and old persons, especially such as have lived in action all their lives, had great employment, much business, much command, and many servants to oversee, and leave off ex abrupto [abruptly], as Charles the Fifth did to King Philip, resign up all on a sudden; they are overcome with melancholy in an instant.

Perhaps Burton knew the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s abdication speech of 1555, which is distinctly melancholy in tone: in the version recorded by his biographer Prudencio de Sandoval, Charles says that he has given up his throne to his son Philip only reluctantly after a long and arduous reign, and mentions ‘that nothing troubled him so much as leaving of [his subjects], but that his want of health rendered him incapable of being longer serviceable to them’.5 A comparable example of someone who retired ex abrupto is King Lear, whose rapid mental deterioration comes as he divests himself of the cares of state. Both a lack of occupation and diminishing strength take their toll on the mind and the body. Burton follows Philipp Melanchthon in claiming it ‘as an undoubted truth … that old men familiarly dote … for black choler’ (i.210).

Though everyone who lives to a certain age eventually succumbs to melancholy, some people are predisposed to it from birth. Melancholy is a hereditary disease. Where we might understand this in genetic terms, Burton and his contemporaries held that a person’s humoral constitution was transmitted through the bodily fluids of parents. The sixteenth-century French physician Jean Fernel argues that any illness that affects the father at the time of conception can be passed on through his semen to the child.6 So, if a father is inclined towards an excess of black bile, the fluid he ejaculates will be of the same condition, and will form a foetus that is similarly inclined to melancholy.

Since older people are prone to melancholy, it is logical that, as the Dutch physician Lieven Lemmens (Lemnius, 1505–68) notes, ‘old men beget most part wayward, peevish, sad, melancholy sons, and seldom merry’ (i.213). Likewise, maternal blood can pass on infirmities. If a woman conceives a child during menstruation, that might result in a sickly child; or, to put it another way, if a child is born sickly, one explanation for this is that it was conceived during the mother’s period. And even behaviour at the time of conception might affect the child’s mind. Burton cites medical authorities who warn that those who have sex on a full stomach, or while drunk, or when they have a migraine are apt to conceive children who are infirm and melancholic.

Such is the intimate relationship between mind and body in Renaissance medical theory that the influence of parents is seen to go even further, imprinting upon their children the stamp of their own mental dispositions. The force of the imagination – especially the female imagin-ation, women being more impressionable according to Galenic theory – can affect the development of the foetus. Thus one explanation for a disability – disconcerting to us – places responsibility on the mother; if she has a fright during pregnancy, her child might be deformed, while ‘if a great-bellied woman see a hare, her child will often have an hare-lip’ (i.215). This perceived effect could even be consciously manipulated. Burton tells the story of a Greek man who was ugly but who wanted to have a ‘good brood of children’. So he bought the most beautiful pictures money could buy to hang in his chamber, ‘that his wife by frequent sight of them, might conceive and bear such children’. One wonders whether the reasoning ever provided a convenient excuse for a woman whose children bore no resemblance to her husband, though Burton does not cast any doubt on the truth of Lieven Lemmens’ claim that ‘if a woman … at the time of her conception think of another man present or absent, the child will be like him’ (i.254–5).

The Melancholy Look

Both physical and mental attributes may be passed on through inheritance (though Renaissance theory allows for the possibility that it sometimes skips a generation), and each person is born with a humoral predisposition that affects their character. Those with a tendency towards an abundance of yellow bile are typically quick-tempered, otherwise known as choleric or bilious. Those rich in blood are sanguine, cheerful and sociable. An abundance of phlegm is associated with a laid-back, stolid temperament and slowness to rise to the bait: a phlegmatic personality. Those with a predominance of melancholy are intelligent and often scholarly, inclined to brooding solitude, but they do not necessarily suffer from melancholy as an illness.

These are the basic contours of the four humours, but the reality is often far more complex. More than one humour can predominate in a body at the same time and these work in combination, in the same way that primary colours blend into a spectrum of different shades. Different proportions might lead to a whole range of emotional dispositions. For example, someone who has a larger proportion of both blood and melancholy than the other two humours may be cheerful, bright in outlook and in mental capacity, while also being introspective.

Such a man was the French essayist Michel de Montaigne (1533–92). When describing himself in ‘On Presumption’, he notes that

my build is tough and thick-set, my face is not fat but full; my complexion is between the jovial and the melancholic, moderately sanguine and hot;

my health is sound and vigorous and until now, when I am well on in years, rarely troubled by illness.7

Montaigne’s self-portrait helpfully draws out important strands of humoral theory. He characterises his complexion – that is, his overall temperament – as a meeting-point between two humours. Though they have opposed qualities, blood being wet and hot while melancholy is dry and cold, these do not cancel one another out. Instead, they incline him towards cheerfulness and sharp intelligence. These two humours do not make him unwell, since they coexist in a stable balance. In another essay he does mention a spell of ‘distempered’ health: ‘it was a melancholy humour (and therefore a humour most inimical to my natural complexion) brought on by the chagrin caused by the solitary retreat I plunged myself into a few years ago, which first put into my head this raving concern with writing’.8 Rather like Burton, Montaigne treats his writing as symptomatic of melancholic imbalance, a form of madness. But for him it is not one that comes naturally, since his predisposition is towards a healthy, sanguine temperament.

For Montaigne, his humoral state goes hand in hand with his physical appearance. His stocky build, his body hair, and his full face are signs of a healthy, moderately sanguine complexion. These elements contribute towards – though are by no means limited to – the self that he explores throughout his essays. It is interesting to note, by way of aside, that the English word ‘complexion’ has narrowed from its earlier Galenic meaning of the proportions of the humours in the body that make up a person’s overall temperament to its modern usage, the colour and texture of the skin. For Montaigne, Burton, and their contemporaries, the complexion of the skin was only one, external indicator of the body’s whole constitution.

Inner and outer states correspond to one another, and the disease of melancholy can be written not only onto how someone feels and behaves, but also onto how they look. Burton draws on two millennia of textbooks to catalogue the visible symptoms of melancholic disorder. According to the ancient Greek writings of the Father of Medicine, Hippocrates, melancholics are

lean, withered, hollow-eyed, look old, wrinkled, harsh, much troubled with wind and a griping in their bellies, or belly-ache, belch often, dry bellies and hard, dejected looks, flaggy beards, singing of the ears, vertigo, light-headed, little or no sleep, and that interrupt, terrible and fearful dreams.

André du Laurens, physician to the French King Henri IV, adds that melancholics experience ‘a kind of itching … on the superficies of the skin, like a flea-biting sometimes’ (i.383).

The contrast between melancholy as a fashionable aristocratic condition of the sixteenth century and melancholy as a chronic disease is a wide one. Those young Elizabethan men who had themselves painted in the voguish posture of melancholy – black clothing, a pale and serious expression, and standing half in shadow – bear little resemblance to the less attractive vision of the condition conjured by medical writers of the same period. And they would probably be less than keen to affect the many bodily symptoms Burton lists, including ‘wind, palpitation of the heart, short breath, plenty of humidity in the stomach … Their excrements or stool hard, black to some, and little’ (i.384). In its bodily manifestations alone, the illness of melancholy was hardly to be welcomed.

Unnatural Melancholy

We have seen what happens when one humour which naturally occurs in the body becomes excessive. When melancholy abounds, it may make the body become distempered: unbalanced and diseased. But one of the curious aspects of melancholy as a disease is that it does not only derive from the humour of the same name. Burton quotes the sixth-century Roman Alexander of Tralles on the subject: ‘there is not one cause of this melancholy, nor one humour which begets, but divers diversely intermixed, from whence proceeds this variety of symptoms’ (i.399). A more extreme and dangerous form of melancholy can arise when any one of the four humours becomes adust: that is, when it comes burnt and corrupt. This is known as ‘unnatural melancholy’ because it does not derive from a humour in its natural state but rather from one that has blackened, which makes it resemble the original form and colour of melancholy.

As the physician Timothy Bright describes the process, when the body becomes too hot – for instance, when the liver becomes overheated, as it did in the Earl of Montfort’s case – then the natural humours may become ‘burned as it were into ashes in comparison of humour, by which the humour of like nature being mixed, turneth it into a sharp lye [an acrid, excremental fluid]: sanguine, choleric, or melancholic, according to the humour thus burned, which we call by name of melancholy’.9 These adust humours behave in different ways from their natur-al forms. Generally they cause harm not only in themselves but also by giving off foul vapours that rise to the brain. These vapours interfere with thoughts, stir passions, and corrupt the imagination. Not everyone agreed that all four humours could create unnatural melancholy. Some medical writers (including Galen and, following him, Bright) excluded phlegm because that humour is white, and how can white become black? But Burton finds enough support to argue that it can. Adustion produces a range of melancholic states, each of which resembles the humour from which it derives.

Phlegm adust is certainly the rarest kind of melancholy. It stirs up ‘dull symptoms, and a kind of stupidity, or impassionate hurt’ (i.400). Because phlegm is the cold and wet humour associated with the element of water (Figure 2.2), melancholics with phlegm adust are drawn to ponds, pools, and rivers. They like to spend a lot of time fishing, but they may also fear water and have dreams that they are drowning. Unlike the typical melancholic who is thin, withered, and restless, these tend to be fat and sleepy. They have an abundance of bodily fluids: they cry a lot, spit a lot, are troubled with rheums (mucus and watery secretions). They may also have delusions of a liquid kind: Burton cites the case treated by the sixteenth-century Spanish physician Cristóbal de Vega of a patient who believed that he was a cask of wine.

Figure 2.2 Phlegmaticus. Engraving by Raphael Sadler (1583).

Those whose melancholy comes from choler adust, on the other hand, are aggressive and short-tempered. They are ‘bold and impudent, and of a more hairbrain disposition, apt to quarrel and think of such things, battles, combats, and their manhood; furious, impatient in discourse, stiff, irrefragable in their tenents; and if they be moved, most violent, outrageous, ready to disgrace, provoke any, to kill themselves, and others’. By contrast to those with phlegm adust, choleric melancholics sleep very little. They are fierce and adventurous, and their melancholy can easily threaten to degenerate into full madness. One of the more exotic symptoms of this kind of melancholy is that sufferers can fall into fits where they speak all kinds of languages they have not been taught. One case of a sufferer from choler adust was an Italian who could ‘make Latin verses when the moon was combust’ – that is, at its closest point to the sun – but was ‘otherwise illiterate’ (i.401).

The illness that arises from blood adust is the exception to the general rule that melancholy is usually accompan-ied by ‘fear and sadness, without any apparent occasion’ (i.170). Sanguine melancholics instead are merry people who laugh a great deal and enjoy singing and dancing. Nonetheless, this manner can erupt into more extreme behaviour, a sign that they are distempered in their humours. Burton recounts a story from a continental medical history of a rural man called Brunsellius who was subject to sanguine melancholy. While he was in church listening to a sermon, he saw a woman fall off a bench, half-asleep. Most of the people who saw the incident laughed, ‘but he for his part was so much moved, that for three whole days after he did nothing but laugh, by which means he was much weakened, and worse a long time following’ (i.401). Burton’s own literary persona of Democritus Junior has some kinship with him, taking after the Greek philosopher who was disposed to laughing in a ‘merry madness’ (‘hilare delirium’, i.400).

Like those who are predisposed towards a healthy, sanguine temperament, those who suffer from sanguine melancholy are ruddy-cheeked, yet the indicators of illness can be read in their features and their behaviour. They have a high colour and a tendency towards redness in the veins of the eyes. Because blood adust tends to overheat the brain, they are subject to delusions. While they enjoy the theatre, they might also imagine that they can see or hear plays. Aristotle tells the story of a man who would sit as if he were at the theatre, ‘now clap his hands, and laugh, as if he had been well pleased with the sight’ (i.400). But it is also sanguine melancholics that Aristotle might have meant when he asked why those who excel in philosophy, politics, poetry or the arts are so often melancholic’.10 At least, that is what the French physician André du Laurens supposed, since sanguine melancholic are often deeply learned, witty, intellectually sharp people.

Finally, there is melancholy adust itself. When black bile becomes corrupted, all of its natural tendencies become more concentrated – a kind of melancholy squared. So sufferers are not only habitually solitary, but may become unable to bear the company of others and suspicious of everyone. Not merely gloomy, they become preoccupied with death, dreaming of graves and corpses. Their fearfulness becomes heightened into wild phobias. And they commonly experience hallucinations of a dark kind: they may become convinced that they see dead people or can talk with devils; they may even believe that they are dead themselves.

The Colour of Melancholy

We have seen that any one of the four humours can cause melancholy when they burn and corrupt, and that it is melancholy’s blackness, in part, which defines its many permutations. The fourteenth-century medical writer Gentile da Foligno had a friend who suffered from melancholy adust and became convinced that a ‘a black man in the likeness of a soldier’ (i.402) was following him about wherever he went. There are several stories of ‘black men’ appearing to melancholics in the Anatomy and it is worth pausing to explore their meaning. We should still be cautious in how we interpret the adjective ‘black’ here: the Latin phrase that Burton translates here is ‘militem nigrum’, and the colour more probably refers to the soldier’s armour or uniform. Similarly, when Burton mentions another example of melancholics who believe that they see and talk with ‘black men’ (i.402), he also quotes the Latin original in which they are ‘monachos nigros’; that is, the ‘black monks’ of the Benedictine order. Here it is their clothing that is black rather than their skin.

But why do melancholics have delusions that they see black-robed Benedictine monks rather than the white-robed Carthusians? The standard explanation is that they are frightened by spectacles of an exterior blackness that is also within them. The medical rationale comes from optical theory, Burton explains:

as he that looketh through a piece of red glass judgeth everything he sees to be red, corrupt vapours mounting from the body to the head, and distilling again from thence to the eye, when they have mingled themselves with the watery crystal which receiveth the shadows of things to be seen, make all things appear of the same colour, which remains in the humour that overspreads our sight, as to melancholy men all is black, to phlegmatic all white, etc.

So visual perception becomes projection outwards of inner gloom, the condensed vapours of black bile forming a kind of melancholy contact lens. Melancholics quite literally see a darkness.

In the poem that prefaces the Anatomy, ‘The Author’s Abstract of Melancholy’, Burton voices the alternating states of being both delighted and afflicted with the disease. One of the stanzas is about auditory and visual illusions:

The ‘black men’ who are the object of terror for this melancholic are supernatural creatures, the phrase being a colloquial term for an evil spirit or bogeyman.11 Nonetheless, the modern racial connotation is not entirely irrelevant, for the colour of these phantoms is part of an ideological construction of a feared other. Renaissance medical theory combines melancholy’s material form and effects with racialised fear and hostility constructed by Europeans.

Just as the black humour affects the sufferer’s perception of others, real or unreal, so it also makes their own melancholy visible to others. One of the hallmarks of natural melancholy – that is, the kind that comes from an excess of the same humour – is a black colour in the face (i.208). Those who suffer from it by inheritance may be born with a dark complexion, or darkening of the features may come on during a period of illness. As we have seen, other humoral types can result in different appearances: sanguine melancholics might have red faces, for instance. As this suggests, Renaissance medicine allows for the idea that physical complexion and even skin colour are not necessarily fixed, and may respond to changes in humoral constitution or even be manipulable.

Humoral theory challenges ideas of otherness even as it reinforces and upholds racial prejudices. A white European melancholic may be terrified of a ‘black man’ he sees, while that other figure is simultaneously the projection of a blackness that is within him. And the characteristics of different humoral types do not just run in families, but also across countries and ethnicities. The sixteenth-century French jurist and political writer Jean Bodin makes a direct connection between dark skin colour and the fact that melancholy is a black humour, claiming that those who live in southern countries are most subject to it. They are more cruel and violent, he argues, and also more lustful, which he sees as the result of ‘spongious melancholy’. A hot climate makes for a larger number of mad men than in the north; Fez, Morocco, and Granada in Spain are particularly prone to it.

At the same time, in the tradition of the pseudo-Aristotelian Problems, people from southern countries are also characterised as wise, contemplative, skilled in the arts, and philosophically inclined: the hot sun of Egypt and Ethiopia is a purifying force that produces peoples who enquire into the secrets of nature and excel at mathematics. By contrast, Bodin argues, the climate of northern countries makes people more inclined to be phlegmatic: cold and dull, chaste, unsubtle, less sharp, but better at obeying and maintaining the law.12 Though connections between humoral types and perceived racial characteristics were common in the period, there was not a full agreement about how they worked. Burton follows Bodin in some respects, but also cites other authorities who claim that people from northern climes are more liable to natural melancholy because the weather is cold and dry, especially near the North Pole (i.239).

To modern eyes, Burton’s views on race and health can appear both forward-thinking and deeply discomforting. In a rare revelation of his own view – rather than of those of his books – he says,

And sure, I think, it hath been ordered by God’s especial providence, that in all ages there should be (as usually there is) once in six hundred years, a transmigration of nations, to amend and purify their blood, as we alter seed upon our land … to alter for our good our complexions, which were much defaced with hereditary infirmities, which by our lust and intemperance we had contracted.

On the one hand, Burton suggests that migration is good for us. It is medically beneficial for altering entrenched humoral complexions and disrupting the associated bad habits of individual nations. The fact that Burton is writing six hundred years after the Norman invasion prompts the idea that another invasion might do Britain good and would even be divinely ordained. But on the other, his language of transmigration and purification also hints at ethnic cleansing, while his example of successful migration is the ‘inundation of those northern Goths and Vandals’ across Europe and beyond; as Mary Floyd-Wilson points out, it is a racialist notion of vigorous northern blood which Burton sees as necessary in order to strengthen the English.13 By invoking God’s special providence, he is calling on the same justification that colonisers used to violent ends in the Americas. The periodic invasion of England by other northern Europeans, he argues, was good for making its inhabitants become as healthy as ‘those poor naked Indians are generally at this day, and those about Brazil …. free from all hereditary diseases or other contagion, whereas without help of physic they live commonly 120 years or more’ (i.213). But he has nothing to say here about the current effects of transmigration on the health of those indigenous people, even though elsewhere he condemns the murder of millions of West Indians by Spanish invaders, documented in horrifying detail by Bartolomé de las Casas (i.58–9).

Melancholy in the Renaissance was deep-rooted in bodies both individually and collectively. Writers from the period used humoral theory to buttress cultural and racial stereotypes, where geography and climate predetermined characteristic types of behaviour. Burton’s larger project is to show ‘that all the world is mad, that it is melancholy, dotes’ (i.39), and global melancholy encompasses the wide variety of sick bodies in their infinite variety of cases on display. In the next chapter, we shall see that melancholy is seen to work at a higher level still: in the stars.