Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part One Affect and Embodied Cognition in Medieval Didactic Texts

- Part Two Sovereignty, Power, and English Textual Identities

- Part Three Acts of Public Record in Making and Sustaining Communities

- Overview Of Career

- The Writings of Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts

- General Index

- Tabula Gratulatoria

- Anglo-Saxon Studies

3 - The Desiring Mind: Embodying Affect in the Old English Pastoral Care

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 May 2022

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part One Affect and Embodied Cognition in Medieval Didactic Texts

- Part Two Sovereignty, Power, and English Textual Identities

- Part Three Acts of Public Record in Making and Sustaining Communities

- Overview Of Career

- The Writings of Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe

- Bibliography

- Index of Manuscripts

- General Index

- Tabula Gratulatoria

- Anglo-Saxon Studies

Summary

POPE GREGORY would have been happier living as a monk. So he explains himself, writing the Regula pastoralis after having been wrenched from a life of secluded contemplation and thrust into the limelight of the papacy in 590. Therefore, his Regula pastoralis arises, as he says, from more than merely his practical desire to instruct the ministers over whom he has authority. The once-reluctant Gregory seeks to address why he had earlier balked at this responsibility, ‘[p]astoralis curae me pondera fugere delitescendo uoluisse’ [had wished to flee from the burdens of pastoral care by concealing myself]. By explaining his circumstances, he seeks moreover to impress upon other ministers the necessity of that reluctance, the magnitude of pastoral responsibility, and the caution demanded by one taking such responsibility upon themselves. From there, ministers are instructed in the means of ministering to various kinds of people in various circumstances – the joyful must temper their joy with sadness, the sad must recall joy. For all circumstances, there are necessary admonitions. Gregory first expounds upon how difficult his own burdens seem to him, how warily the power and authority of positions such as his own ought to be approached, and, from thence, how others who govern should approach this task when it falls to them. To Gregory, power should never be actively sought, and all to whom it might fall must criticize their own motives.

But the Old English translation of the Regula pastoralis has its own problems. In the ninth-century English court of King Alfred the Great, the text similarly positions itself as the work of an authority figure, in this case ostensibly a translation by the king himself. Yet while Gregory treats authority as a burden to be assumed, the Old English text laments the vulnerability of English authority:

ða gemunde ic eac hu ic geseah, ærðæmðe hit eall forhergod wære 7 forbærned, hu ða ciricean giond eall Angelcynn stodon maðma 7 boca gefyldæ ond eac micel menigeo Godes ðiowa 7 ða swiðe lytle fiorme ðara boca wiston.

[Then I remembered how I saw, before they were all plundered and burnt, how the churches stood throughout all England filled with treasures and books and also there was a great number of God's servants, and those knew very little benefit from those books.]

- Type

- Chapter

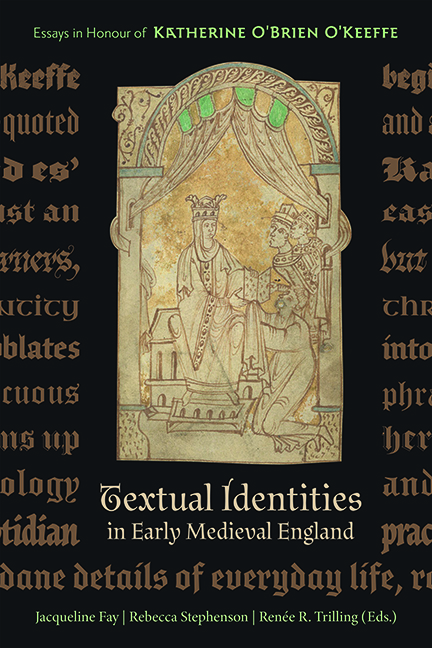

- Information

- Textual Identities in Early Medieval EnglandEssays in Honour of Katherine O'Brien O'Keeffe, pp. 54 - 69Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022

- 1

- Cited by