Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 August 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Summary

In this essay I look at a group of texts written in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, which were initially circulated in manuscript as contributions to the ‘Lollard’ debates about church wealth and clerical morality in that period. They were then printed in the early 1530s (and reprinted in the 1560s and 1570s) as contributions to similar debates a century and more later than their origin. These texts, Lollard writing re-presented for Reformation reading, offer an interesting case study of chronological and epistemological distortion, as they might be argued to distort conceptions of time and history around them both ‘positively’ and ‘negatively’ – if those terms have any meaning – but always powerfully and provocatively. The texts present challenges to our definitions of how they might be categorised, what they might suggest about the communities that produced and received them, and what they imply about our own sense of their relationship to time and the creation of historical narrative.

Late medieval works printed in the Tudor period have generally been read, explicitly or implicitly, in terms of the posthumous or the undead, as examples of the ‘afterlives’ of medieval writings. But I want to consider them here not only as revenants, things not quite dying, but also as things not quite new-born, as contributions to the work in progress of the never entirely achieved project of English religious Reformation. So, in so far as they might be distortions of late-medieval authorial intentions, disinterred and reanimated by Tudor printers, they are also elements of a new reformed typology of protest, fresh texts offered to new readers as part of a campaign to free hearts and minds allegedly long-manacled by the old lies of catholic deception. As we shall see, both their novelty and their antiquity were central to their presentation and reception.

To begin very simply: these texts certainly distort modern readers’ perceptions of the terms of debate in the early exchanges of Henry VIII's Reformation, with polemical claim and counter-claim clouding any clear sense of the facts at issue. Just how much wealth did the Tudor Church possess?

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

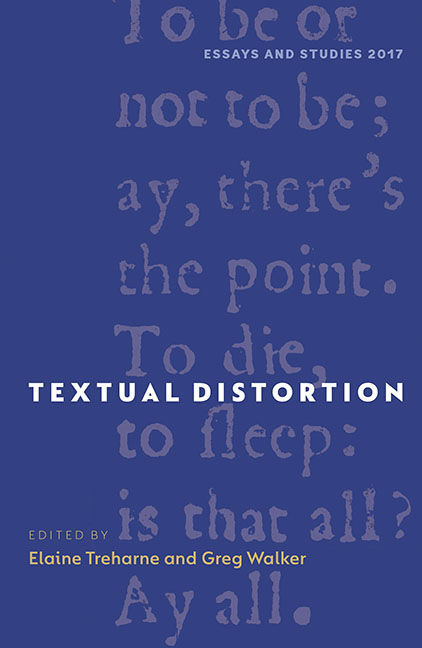

- Textual Distortion , pp. 130 - 149Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017

- 1

- Cited by