Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

The Presence of the Book

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 August 2019

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction

- The Curious Production and Reconstruction of Oxford, Bodleian Library, Junius 85 and 86

- ‘Through a glass darkly’, or, Rethinking Medieval Materiality: A Tale of Carpets, Screens and Parchment

- Distortion, Ideology, Time: Proletarian Aesthetics in the Work of Lionel Britton

- Shakespeare and Korea: Mutual Remappings

- Dictionary Distortions

- Where Do Indigenous Origin Stories and Empowered Objects Fit into a Literary History of the American Continent?

- Distortion in Textual Object Facsimile Production: A Liability or an Asset?

- The Uncanny Reformation: Revenant Texts and Distorted Time in Henrician England

- The Presence of the Book

- Index

Summary

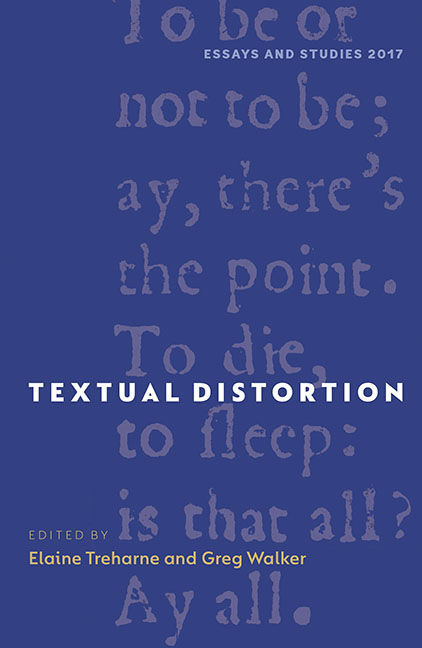

When Harold Bloom wrote that all reading was misreading, that all prision was in fact misprision, and that poets learned from and imitated their forerunners by misreading them, he inaugurated a now well-established school of literary aesthetics. For Bloom, the material means by which a text was transmitted from a writer to a reader was in itself apparently unproblematic. He happily reified mediation in his impatience to delineate the shaping force of literary history. In fact, the study of distortion shows that, in a sense, Bloom is exactly wrong. All reading is correct reading, because each textual artefact is unique.

Distortion is the moment at which the physical means of transmitting a text irrupt into a reader's experience of it. I will discuss distortion here as a phenomenon occurring in printed materials, but I do not wish to exclude other recognisable instances such as static in a radio signal, or white noise on a cathode-ray-tube television screen. To speak of distortion as an impairment, however, is to confirm the Platonic priority of another book-object. As textual scholars have shown, locating this authoritative ur-text can be, to say the least, difficult. Distortion is not a condition befalling individual textual artefacts (‘book-objects’) here and there: there is no non-distorted reading. In fact, a belief in non-distorted reading amounts to believing in pure, transparent mediation that leaves no trace of itself on the mediated. Leaving aside for the purposes of this essay the profound political implications of placing the labour of mediation under erasure, I will offer here a heuristic of distortion. Absent such a heuristic, ‘distorted’ book-objects and their texts will always be treated as degraded derivatives. The corollary of that treatment is to elevate an unknown, possibly non-existent ur-text to a position of unimpeachable authority, and to degrade both the experience of reading and of the embodied text and reader. We can solve the problem of distortion by placing the irreducible phenomenological singularity of the book-object at the centre of our experience of a text. This is existential reading: you are reading what you are reading and not anything else.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Textual Distortion , pp. 150 - 166Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2017