Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: St Edmund's Medieval Lives

- 1 King, Martyr and Virgin: Imitatio Christi in Ælfric's Life of St Edmund

- 2 Chronology, Genealogy and Conversion: The Afterlife of St Edmund in the North

- 3 Geoffrey of Wells’ Liber de infantia sancti Edmundi and the ‘Anarchy’ of King Stephen's Reign

- 4 Music and Identity in Medieval Bury St Edmunds

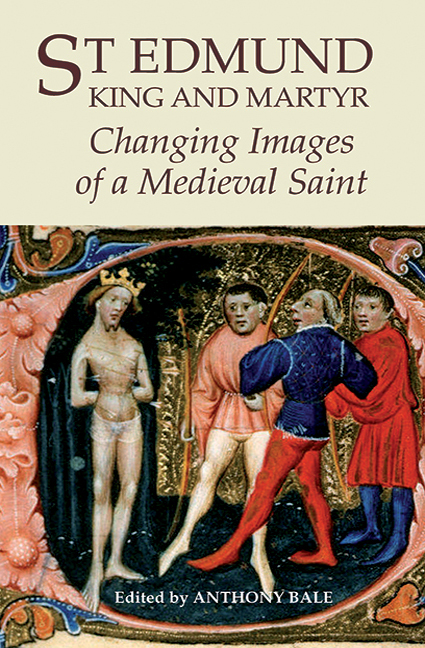

- 5 Medieval images of St Edmund in Norfolk Churches

- 6 John Lydgate's Lives of Ss Edmund and Fremund: Politics, Hagiography and Literature

- 7 St Edmund in Fifteenth-Century London: The Lydgatian Miracles of St Edmund

- 8 The Later Lives of St Edmund: John Lydgate to John Stow

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

2 - Chronology, Genealogy and Conversion: The Afterlife of St Edmund in the North

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 May 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: St Edmund's Medieval Lives

- 1 King, Martyr and Virgin: Imitatio Christi in Ælfric's Life of St Edmund

- 2 Chronology, Genealogy and Conversion: The Afterlife of St Edmund in the North

- 3 Geoffrey of Wells’ Liber de infantia sancti Edmundi and the ‘Anarchy’ of King Stephen's Reign

- 4 Music and Identity in Medieval Bury St Edmunds

- 5 Medieval images of St Edmund in Norfolk Churches

- 6 John Lydgate's Lives of Ss Edmund and Fremund: Politics, Hagiography and Literature

- 7 St Edmund in Fifteenth-Century London: The Lydgatian Miracles of St Edmund

- 8 The Later Lives of St Edmund: John Lydgate to John Stow

- Select Bibliography

- Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

The first history of Iceland, indeed probably the earliest written text in the Icelandic vernacular, is the Íslendingabók (‘Book of the Icelanders’), written sometime between 1122 and 1133 by Ari Þorgilsson. It is a text at the interface of oral and written cultures, for Ari derived much of his material from oral sources, learned people whom he enumerates in his text; at the same time he was attempting to provide a chronological framework by reference to events beyond the confines of the Nordic world. The very first of these references is that which establishes the date of the settlement of Iceland in the year 870. I quote the whole of Ari's long and awkward sentence – the writing of narrative prose in the vernacular was in its infancy – since it demonstrates his customary combination of reference to oral informants with information culled from wider international sources:

Ísland byggðisk fyrst ýr Norvegi á dǫgum Haralds ens hárfagra, Halfdanarsonar ens svarta, í þann tíð – at ætlun ok tǫlu þeira Teits fóstra míns, þess manns es ek kunna spakastan, sonar Ísleifs byskups, ok Þorkels fǫðurbróður míns Gellissonar, es langt munði fram, ok Þóríðar Snorradóttur goða, es bæði vas margspǫk ok óljúgfróð, – es Ívarr Ragnarssonr loðbrókar lét drepa Eadmund enn helga Englakonung; en þat vas dcclxx. vetra eptir burð Krists, at því es ritit es í sǫgu hans.

(‘Iceland was first settled from Norway in the days of Haraldr hárfagri, son of Hálfdan inn svarti, at the time – according to the opinion and reckoning of my foster father Teitr, the wisest man I know, son of Bishop Ísleifr, and of my uncle Þorkell Gellisson, who remembered far back, and of Þóríðr, daughter of Snorri goði, who was both very wise and truthful – when Ívarr, the son of Ragnarr loðbrók, had Edmund, the holy king of the English, killed; and that was 870 years after the birth of Christ, according to what is written in his saga.’)

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- St Edmund, King and MartyrChanging Images of a Medieval Saint, pp. 45 - 62Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2009