Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Cinema's Grey Spaces

- 1 A Wider Audience: Robert Rauschenberg, the White Paintings and CinemaScope

- 2 The Screen Scene: Andy Warhol, the Factory and Home Movies

- 3 Private Dis-Pleasures: Mona Hatoum, Mediated Bodies and the Peep Show

- 4 A Monument in Ruins: Douglas Gordon, Screen Archaeology and the Drive-in

- Conclusion

- Index

2 - The Screen Scene: Andy Warhol, the Factory and Home Movies

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 September 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Cinema's Grey Spaces

- 1 A Wider Audience: Robert Rauschenberg, the White Paintings and CinemaScope

- 2 The Screen Scene: Andy Warhol, the Factory and Home Movies

- 3 Private Dis-Pleasures: Mona Hatoum, Mediated Bodies and the Peep Show

- 4 A Monument in Ruins: Douglas Gordon, Screen Archaeology and the Drive-in

- Conclusion

- Index

Summary

Film- and performance-based art was still a rarity in most museum and gallery spaces in the mid-1960s, yet it had decisively entered the studio, the co-op and related contemporary art settings. In North America, Europe and elsewhere, screenings, concerts, recitals, readings, environments and other forms of performative, interactive production had become an integral part of what would be called the neo-avant-garde. Gaining purchase in the trans-media historical avant-garde that included Constructivism, Dada and Surrealism – instead of the seeming entropic path laid out by Abstract Expressionism and ‘advanced’ painting – Happenings and Pop, Fluxus, Minimal and Conceptual art dissolved barriers of media specificity by emphasising performance, spectacle and duration as components (or the totality) of the piece. A decade after the Stable Gallery exhibition, Robert Rauschenberg's White Paintings had become almost quaint by comparison.

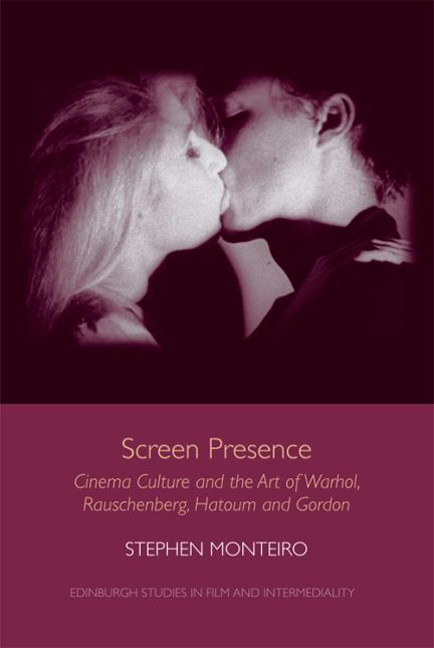

Within this context, Andy Warhol would establish an art career of continuous collaboration, shaped by the synthesis of media and social interaction. A major aspect of this Gesamtkunstwerk was Warhol's film-based social practices throughout the 1960s, which are increasingly recognised as one of his greatest artistic legacies. Warhol's production and exhibition methods of the period relied heavily on vernacular film culture, particularly home-movie practices, to transform film into a binding thread of the large, motley group of personalities that formed his Factory studio community (Figure 2.1). ‘It was people who were fascinating,’ Warhol explains in POPism, his 1960s memoir co-written with Pat Hackett, ‘and I wanted to spend all my time being around them, listening to them, and making movies of them.’ While the frequent appearance of his films in museums and galleries today may represent validation for works that received little public affection when they were made, the conditions of their exhibition – often looped digital-video transfers presented like slow-moving paintings – regularly dissociate them from their initial use as mechanisms in the construction of collective identity. Just as home movies tend to privilege practice – the making and sharing – over the object in their contribution to social cohesion, Warhol's films before 1966 constituted a social practice primarily centred on and in the Factory as a discrete community. As Warhol later claimed, ‘We didn't think of our movies as underground or commercial or art or porn; they were a little of all those, but ultimately they were “our kind of movie”’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Screen PresenceCinema Culture and the Art of Warhol, Rauschenberg, Hatoum and Gordon, pp. 58 - 101Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2016