Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

6 - A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

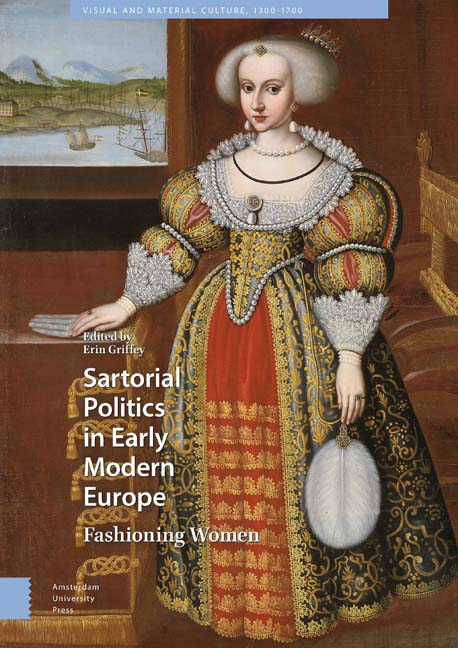

Summary

Abstract

This chapter discusses how figurative pieces of jewellery could function as statements of identity, allegiance, and belonging for early modern royal women. Focussing on Anna of Denmark (1574–1619), it examines extant jewellery accounts and portraits to establish patterns in her patronage and modes of representation. It thus extends our understanding of the type and frequency of Anna's jewellery purchases, arguing that she strategically used her bodily display to visualise her dynastic identity and her support for a Stuart-Habsburg marriage alliance. The possibility that this was a practice learnt at her natal court in Denmark is addressed, along with the role that jewellery played for the Stuart queen consort in the highly politicised world of gift exchange.

Key words: Anna of Denmark; Stuart court; jewellery; portraiture; gift exchange

The early modern body was not a neutral or natural being, but a sociopolitical entity constructed through the considered use of apparel, accessories, and movement. In her influential rethinking of the centrality of the body to subjectivity, the feminist theorist Elizabeth Grosz powerfully argues that ‘the body must be regarded as a site of social, political, cultural, and geographic inscriptions, production, or constitution’, going on to state that ‘it is itself a cultural, the cultural product’. Indeed, as scholars commonly recognise, the pieces of clothing and jewellery worn on the elite early modern body were fashioned from costly materials that required expert craftsmanship, thereby making manifest the wearer's financial and social position. But further, multiple codes of meaning were tied up in bodily adornment, which could give expression to such constructs as gender, sexuality, authority, piety, purity, or networks of belonging. Importantly for royal and elite early modern women, this was a powerful political tool that they could access and control: by making specific sartorial and jewellery choices, they could legitimise a position, visualise political ambition, or show allegiance, favour, or dynastic membership. Indeed, the recent turn in early modern dress history, pioneered by cultural historians including Eva Andersson, Sylvène Édouard, Isabelle Paresys, Ulinka Rublack, and Laura Oliván Santaliestra, has underscored the ways in which dress was read as a signifier of the wearer’s identity – whether that be economic, social, national, or religious.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sartorial Politics in Early Modern EuropeFashioning Women, pp. 139 - 160Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019

- 1

- Cited by