Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

10 - ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

- Frontmatter

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Isabella d’Este's Sartorial Politics

- 2 Dressing the Queen at the French Renaissance Court: Sartorial Politics

- 3 Dressing the Bride: Weddings and Fashion Practices at German Princely Courts in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries

- 4 Lustrous Virtue: Eleanor of Austria's Jewels and Gems as Composite Cultural Identity and Affective Maternal Agency

- 5 Queen Elizabeth: Studded with Costly Jewels

- 6 A ‘Cipher of A and C set on the one Syde with diamonds’: Anna of Denmark's Jewellery and the Politics of Dynastic Display

- 7 ‘She bears a duke's revenues on her back’: Fashioning Shakespeare's Women at Court

- 8 How to Dress a Female King: Manifestations of Gender and Power in the Wardrobe of Christina of Sweden

- 9 Clothes Make the Queen: Mariana of Austria's Style of Dress, from Archduchess to Queen Consort (1634–1665)

- 10 ‘The best of Queens, the most obedient wife’: Fashioning a Place for Catherine of Braganza as Consort to Charles II

- 11 Chintz, China, and Chocolate: The Politics of Fashion at Charles II's Court

- 12 Henrietta Maria and the Politics of Widows’ Dress at the Stuart Court

- Works Cited

- Index

Summary

Abstract

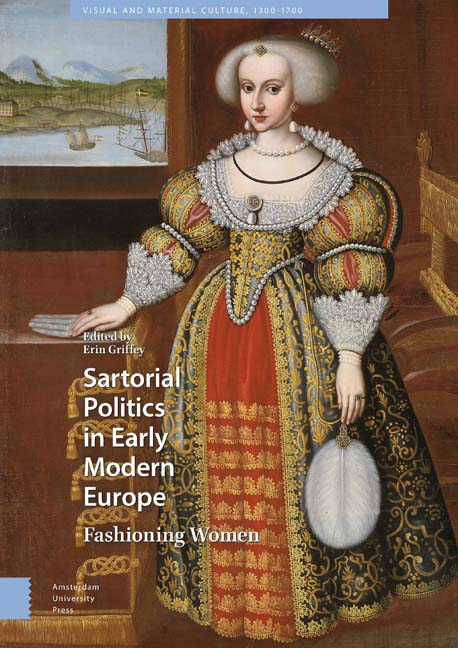

Catherine of Braganza and those around her used her role as Charles II's wife to fashion a very specific image for her: that of the good wife. In this role, she served as a model for other women to follow that was in marked contrast to the king's mistresses, who traded on being bad. Her Portuguese roots were both appealing in terms of her links to exotic goods coming into the country, and negative in marking her out as a foreigner, while her piety was both admired and feared. Fashionable dress, furnishings, and a range of commemorative objects were exploited to promote the queen and the royal marriage both at the time of her wedding and throughout the reign.

Key words: Catherine of Braganza; mistresses; Portugal/Portuguese; Catholicism; clothing; furnishings

Introduction

By the end of her life, Catherine of Braganza (1638–1705) (Figure 10.1) was under no illusions about the nature of royal marriage. She bitterly resented being sent to England in 1662 ‘solely for the advantage of Portugal, & for this cause & for the interests of our House I was Sacrific’d’. While her family might have sacrificed her, Charles II (1630– 1685) hurt her more by his infidelity in spite of his intentions to be a ‘good’ husband. The firm rebuke that Charles received from his sister Henriette Anne, otherwise known as Minette, is telling. She wrote ‘Here people say that she is in the deepest distress and to speak frankly I think she has only too good reason for her grief.’ While Catherine came to forgive her husband, as a Catholic bride from Portugal, she received a mixed reception in England, ranging from Lancelot Reynolds's description of her as a ‘blest soul’ and ‘a gracious queen’ to an anonymous poet's far less flattering ‘Ill-natured little goblin’. In keeping with her image as ‘a gracious queen’, Catherine has traditionally been presented as politically and personally passive. However, this chapter offers an alternative view of Catherine, arguing that she played the part of a ‘good wife’ to assert – quietly but firmly ‒ her position as queen and thereby came to represent normative, virtuous, women at court and in the country at large. Using clothing, furnishings, portraiture, and other material goods, Catherine fashioned her legitimate place as queen consort, a role that others were keen to promote on her behalf.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sartorial Politics in Early Modern EuropeFashioning Women, pp. 227 - 252Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019