Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

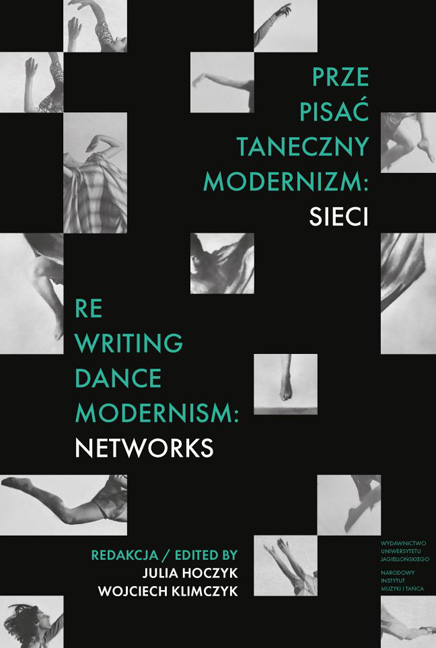

- Prze-pisać taneczny modernizm: sieci

- Metodologie: usieciowianie tanecznego modernizmu

- Transmisje: transnarodowe trajektorie tanecznego modernizmu

- Poszerzenia: taneczny modernizm w słowiańskiej Europie Środkowej

- Methodologies: Networking Dance Modernism

- Transmissions: Transnational Trajectories of Dance Modernism

- Expansions: Dance Modernism in Slavic Central Europe

- Biogramy autorów

- Authors’ Biographies

- Indeks / Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Jewish Tango and the Question of Identity

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 March 2024

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Prze-pisać taneczny modernizm: sieci

- Metodologie: usieciowianie tanecznego modernizmu

- Transmisje: transnarodowe trajektorie tanecznego modernizmu

- Poszerzenia: taneczny modernizm w słowiańskiej Europie Środkowej

- Methodologies: Networking Dance Modernism

- Transmissions: Transnational Trajectories of Dance Modernism

- Expansions: Dance Modernism in Slavic Central Europe

- Biogramy autorów

- Authors’ Biographies

- Indeks / Index

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

- Miscellaneous Endmatter

Summary

The dynamic changes that occurred in dance aesthetics and kinaesthetic techniques in the first two decades of the twentieth century were most visible in Germany and France. These two countries were the first ones to witness the emergence of the choreographies that anticipated modernist dance styles and genres, which took place against the broad background of the avant-garde movement in various forms of art. Furthermore, Germany and France were the countries where the foundations of new movement theories were laid that not only concerned artistic dance but also popular body culture. Thus, it is no wonder that artists from these countries were most open to influences from North America and they knew how to use them to reform dance on the old continent. The increasingly numerous German and French dance companies and schools were very successful in attracting artists from other countries and especially from Central and Eastern Europe, where many nations, including Poland, did not have their own independent states, or even their own national cultural institutions. Therefore, one may argue that till the end of the Great War, the channels through which the ideas and techniques of modernist dance were spread were rather limited and unidirectional, as dance practitioners from Central and Eastern Europe educated themselves and developed their dance techniques in Western European centers, where they created their own concepts of stage movement and where they usually continued their dance careers. Rudolf Laban was born in Presburg (Bratislava) in what is now Slovakia; Rosalia Chladek came from Brünn (Brno) in the Czech Republic; Warsaw was Marie Rambert's city of birth; Vaslav Nijinsky, who had Polish parents, was born in Kiev in Ukraine, while his sister Bronislava – in Minsk in Belarus, to name but a few examples. Thus, due to the artists’ migration to German and French cultural centers, European modernist dance was from the very beginning a transnational and transcultural phenomenon.

The situation changed dramatically in 1918, when the war ended and the political map of Europe was radically redrawn. The regaining of independence by, for instance, Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, and Czechoslovakia gave a strong impulse to the creation of new national artistic institutions and to the idea of expressing one's own national identity through art.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Re-writing Dance Modernism: Networks , pp. 485 - 508Publisher: Jagiellonian University PressPrint publication year: 2023