Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

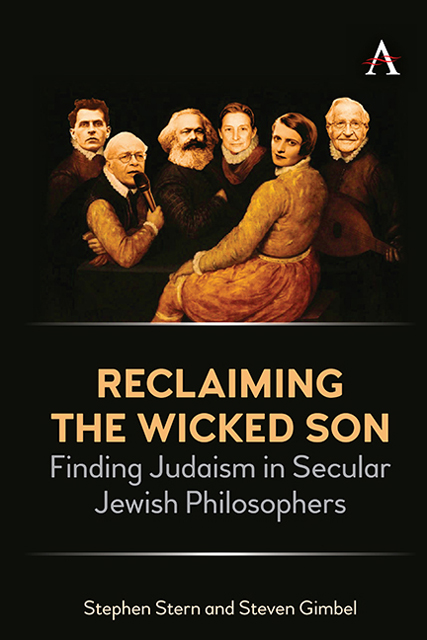

- Introduction: Reclaiming the Wicked Son

- 1 Karl Marx and Materialistic Messianism

- 2 Ludwig Wittgenstein and Neo-Talmudic Thought

- 3 Ayn Rand and the Hassidic Courts

- 4 Peter Singer: The Amos of Anim

- 5 Judith Butler and Orthopraxy

- 6 Noam Chomsky, Kabbalist

- Conclusion: Re-Membering the Tribe

- Bibliography

- Index

6 - Noam Chomsky, Kabbalist

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 January 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Reclaiming the Wicked Son

- 1 Karl Marx and Materialistic Messianism

- 2 Ludwig Wittgenstein and Neo-Talmudic Thought

- 3 Ayn Rand and the Hassidic Courts

- 4 Peter Singer: The Amos of Anim

- 5 Judith Butler and Orthopraxy

- 6 Noam Chomsky, Kabbalist

- Conclusion: Re-Membering the Tribe

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Judaism is a linguistic religion. The ancient Egyptians worshipped their Pharaohs, human beings with bodies who were made into gods. Other tribes had idols, material sculptures that they deified by placing supernatural powers into a natural object. But for Jews, there is only language.

The First Commandment, a set of words, demands that the focus of all belief be about words. God has no material body, no physical (much less physiological) depiction can be constructed. The closest thing Jews have to a representation is a name, an ordered arrangement of letters which they are forbidden from pronouncing. Jews have only a word and yet they are denied the opportunity of using it as they use other words. Instead of saying the sound of the word aloud, they utter the syllables hashem, the word for “the name.” The name itself, the linguistic representation of the Divine, is a vessel of its own divinity. The word contains the power of the thing the word desig nates, that is, there is no real distinction between word and object, between signifier and signified, at least for God Himself. What made Judaism unique among ancient religions is that it became about language.

Jews are called “the People of the Book.” A book, in one sense, is a material object, pages of printed paper or scrolls of inscribed sheepskin. And Jews treat each copy of their book as holy, precluded from touching it, indirectly conveying their affection and respect through kissing it.

Yet, in another sense, the book is not physical at all. The printed versions of the book are just that, versions, mere instantiations. The book is not in the publishing, it is in the ordering of letters and blank spaces. It is in the meaning—or better, the meanings—of the language. Every book is a collection of thoughts, that is, immateriality, that is somehow made material. It is something ephemeral that is yet capable of having traces turned into physical markings that are accessible to the senses which then go on to give rise once again to the ideas it contains. The immaterial made material only to then disclose its immateriality—how could one not see this process as profound, if not magical?

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Reclaiming the Wicked SonFinding Judaism in Secular Jewish Philosophers, pp. 99 - 120Publisher: Anthem PressPrint publication year: 2022