Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

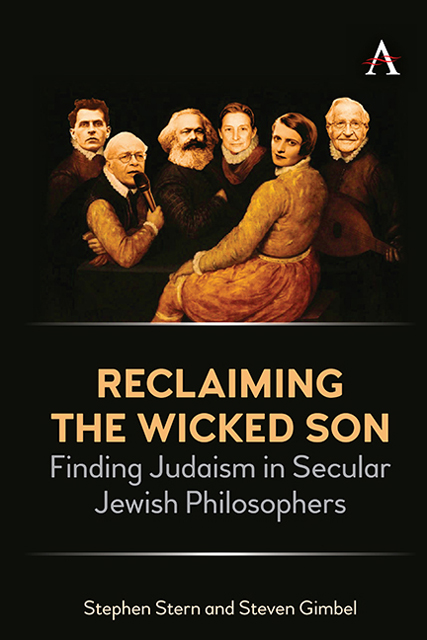

- Introduction: Reclaiming the Wicked Son

- 1 Karl Marx and Materialistic Messianism

- 2 Ludwig Wittgenstein and Neo-Talmudic Thought

- 3 Ayn Rand and the Hassidic Courts

- 4 Peter Singer: The Amos of Anim

- 5 Judith Butler and Orthopraxy

- 6 Noam Chomsky, Kabbalist

- Conclusion: Re-Membering the Tribe

- Bibliography

- Index

5 - Judith Butler and Orthopraxy

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 January 2023

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction: Reclaiming the Wicked Son

- 1 Karl Marx and Materialistic Messianism

- 2 Ludwig Wittgenstein and Neo-Talmudic Thought

- 3 Ayn Rand and the Hassidic Courts

- 4 Peter Singer: The Amos of Anim

- 5 Judith Butler and Orthopraxy

- 6 Noam Chomsky, Kabbalist

- Conclusion: Re-Membering the Tribe

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

In the 1990s, Judith Butler helped launch Queer Studies as an academic field. Her masterwork Gender Trouble not only challenged the mainstream understanding of sex, gender and sexuality, but showed that even the feminist thinkers at the time were keeping themselves trapped in an orthodox notion of gender.

Butler challenged orthodoxy. This is not only meant in the sense of taking on entrenched received views, but in the deeper sense in which the contemporary Jewish movement of orthopraxy is taking on Jewish orthodoxy. The word orthodoxy means correct belief and orthopraxy means correct action. Like Jewish orthopraxy writers such as Jeffrey Radon and Sherwin Wine who argue that Judaism is not a set of beliefs one must hold but rather to be Jewish is to engage in certain ways of acting, Butler argues that gender is not some culturally imprinted way of thinking that comes from being socialized as a man or woman but rather that gender “is a doing,” a set of prescribed behaviors within political structure which pre-determines the boundaries of allowable and meaningful acts. Just like the Jewish orthorpraxy writers, Butler takes what you do to determine what you are.

Butler is a secular Jewish writer, but she had a religious upbringing, albeit a contentious one. She went to a Jewish day school, but got into trouble for talking back to the teachers and cutting classes.

They told me that I couldn't go to the school anymore, to the Jewish education program anymore unless I studied privately with the rabbi. This was for me terrific because I loved the rabbi—in fact, I skipped the class, my regular Hebrew class in order to go into the sanctuary to listen to the rabbi speak and the rabbi spoke about extraordinary things (his name was Daniel Silver and he wrote a book on Moses). So, when I was forced to have a tutorial with him I was privately very happy and he asked me what I wanted to study. He was very suspicious of me because I was this problem child. And I told him I wanted to know why Spinoza was excommunicated from the synagogue, I wanted to know whether German idealist philosophy was linked to the rise of Nazism, and I wanted to understand existential theology. I was fourteen years old.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Reclaiming the Wicked SonFinding Judaism in Secular Jewish Philosophers, pp. 75 - 98Publisher: Anthem PressPrint publication year: 2022