Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- 11 ‘He was black, he was a White man, and a dinkum Aussie’: race and empire in revisiting the Anzac legend

- 12 The quiet Western Front: the First World War and New Zealand memory

- 13 ‘Writing out of opinions’: Irish experience and the theatre of the First World War

- 14 ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

- 15 Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

- Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

- Index

- References

15 - Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- 11 ‘He was black, he was a White man, and a dinkum Aussie’: race and empire in revisiting the Anzac legend

- 12 The quiet Western Front: the First World War and New Zealand memory

- 13 ‘Writing out of opinions’: Irish experience and the theatre of the First World War

- 14 ‘Heaven grant you strength to fight the battle for your race’: nationalism, Pan-Africanism and the First World War in Jamaican memory

- 15 Not only war: the First World War and African American literature

- Afterword Death and the afterlife: Britain's colonies and dominions

- Index

- References

Summary

In a column for the Chicago Defender published just following the Second World War, the African American poet Langston Hughes has his Harlemite barfly Jesse B. Semple (or ‘Simple’) say the following:

‘You know Buddy Jones’ brother, what was wounded in the 92nd in Italy, don't you? Well, he was telling me about how bad them rednecks treated him when he was in the army in Mississippi. He said he don't never want to see no parts of the South again. He were born and raised in Yonkers and not used to such stuff. Now his nerves is shattered. He can't even stand a Southern accent no more.'

‘Jim Crow shock,’ I said. ‘I guess it can be as bad as shell shock.’

‘It can be worse,’ said Simple. ‘Jim Crow happens to men every day down South, whereas a man's not in a battle every day.’

Although ostensibly written about a different conflict, Hughes's association of battlefield trauma with the traumas of racial segregation in the USA was one forged in the experiences of the First World War. Shell shock troubled distinctions between organicist and psychological notions of trauma; it was exacerbated by feelings of helplessness in conflict situations. Such a blend of psychological and physical stress and coercion was familiar to African Americans living under Jim Crow, and Hughes's bleak humour suggests that its everyday status only prolonged that trauma rather than dulled it.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

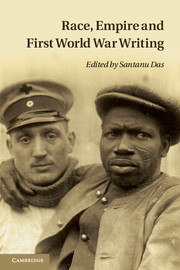

- Race, Empire and First World War Writing , pp. 283 - 300Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011