Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- 6 Representing Otherness: African, Indian and European soldiers' letters and memoirs

- 7 Living apart together: Belgian civilians and non-white troops and workers in wartime Flanders

- 8 Nursing the Other: the representation of colonial troops in French and British First World War nursing memoirs

- 9 Imperial captivities: colonial prisoners of war in Germany and the Ottoman empire, 1914–1918

- 10 Images of Te Hokowhitu A Tu in the First World War

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- Index

- References

7 - Living apart together: Belgian civilians and non-white troops and workers in wartime Flanders

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 February 2014

- Frontmatter

- Contents

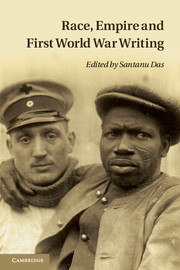

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on contributors

- Introduction

- PART I VOICES AND EXPERIENCES

- PART II PERCEPTIONS AND PROXIMITIES

- 6 Representing Otherness: African, Indian and European soldiers' letters and memoirs

- 7 Living apart together: Belgian civilians and non-white troops and workers in wartime Flanders

- 8 Nursing the Other: the representation of colonial troops in French and British First World War nursing memoirs

- 9 Imperial captivities: colonial prisoners of war in Germany and the Ottoman empire, 1914–1918

- 10 Images of Te Hokowhitu A Tu in the First World War

- PART III NATIONALISM, MEMORY AND LITERATURE

- Index

- References

Summary

In Belgium, the front line ran for fifty kilometres, from Nieuport on the coast to Ploegsteert on the French–Belgian border. The deadlock here began in October 1914 with the Battle of the Yser and the First Battle of Ypres, and ended on 28 September 1918, when the war of movement finally resumed with the ‘Liberation Offensive’. The war-stricken zone was the southern part of the province of West Flanders, a sparsely populated rural backwater better known under its unofficial name Westhoek (West Corner). The front line ran through or near the towns of Nieuport (Nieuwpoort), Dixmude (Diksmuide) and Ypres (Ieper), while Furnes (Veurne) and Poperinghe (Poperinge) formed the backbone of the rear area. These five towns were all small in size – none had more than 17,000 inhabitants – but had a rich cultural heritage. The language spoken in this region was a local dialect, one of the many Flemish versions of Dutch. In September and October 1914, many refugees from the more eastern parts of Belgium arrived here, spurred by the German advance. Some stayed in Flanders' Westhoek; most, however, continued their flight and ended up in France or the United Kingdom. The local inhabitants, who held on in their own region, were marginalised not only by the refugees, but also by thousands of troops. In the Yser area (Nieuport–Dixmude), the majority of the military belonged to the Belgian army, but near Ypres and Poperinghe, it was a multinational and multiracial force that occupied the territory.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Race, Empire and First World War Writing , pp. 143 - 157Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2011

References

- 3

- Cited by