Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Maps

- 1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam

- 2 Java

- 3 Japan

- 4 China: The Guqin Zither

- 5 Chinese Opera

- 6 North India

- 7 South India

- 8 Mande Jaliyaa

- 9 North American Jazz

- 10 Europe

- 11 North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean: Andalusian Music

- 12 The Eastern Arab World

- 13 Turkey

- 14 Iran

- 15 Uzbekistan and Tajikistan

- Notes

- Bibliographies

- Index

14 - Iran

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Maps

- 1 Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam

- 2 Java

- 3 Japan

- 4 China: The Guqin Zither

- 5 Chinese Opera

- 6 North India

- 7 South India

- 8 Mande Jaliyaa

- 9 North American Jazz

- 10 Europe

- 11 North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean: Andalusian Music

- 12 The Eastern Arab World

- 13 Turkey

- 14 Iran

- 15 Uzbekistan and Tajikistan

- Notes

- Bibliographies

- Index

Summary

In a garden of cypress and pine trees under the soft summer night, tiny water-canals and candlelit paths lead to a polygonal kiosk open on all sides, with an open dais in front. Six cushions in a half-moon arrangement face an audience – men and women, young and old – seated around the stage. From behind the pavilion appear six young musicians: five men with instruments, and a woman in a white evening dress with long sleeves and high neckline; her companions are in white shirts and beige trousers. To applause they take their places on the dais and the men tune their instruments: a lute, fiddle, zither, flute and drum. Each instrumentalist is highlighted during a slow introduction, which is followed by a rapid virtuoso section on zither and drum. Singing in Farsi, the vocalist delivers an evocative line: ‘On my tomb, sit down with wine and a musician’, and the forcefully-plucked lute gives an improvised response. The two continue their exchange while members of the audience gently nod as they sing along in a whisper. The meditative mood gives way to an energetic song from singer and ensemble, and the performance ends with a lively instrumental number.

WE are in the garden of the Hāfezieh, where the Persian poet Hāfez (1326– 90) is buried. This is in Shiraz, also known as the city of Gol o Bolbol (‘flower and nightingale’). Such gardens have been popular venues for the performance of Persian classical music for centuries, and for musicians, poets and philosophers they have been a refuge from daily life, with many – like the twelfth-century poet, mathematician and philosopher Omar Khayyām – choosing to be buried there: ‘My grave will be in a spot where, every spring, the north wind will scatter blossoms on me.’

The story goes that a Persian poet was discussing music with some Westerners who compared their music to an ocean, and Persian music to a miserable drop. ‘Indeed,’ answered the poet, ‘but that ocean is only water, while this drop is a tear’. Essentially intimate, Persian classical music is closely bound up with poetry and mysticism, and customarily involves the singing of verses by poets such as Hafez, Sa’di and Rumi.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

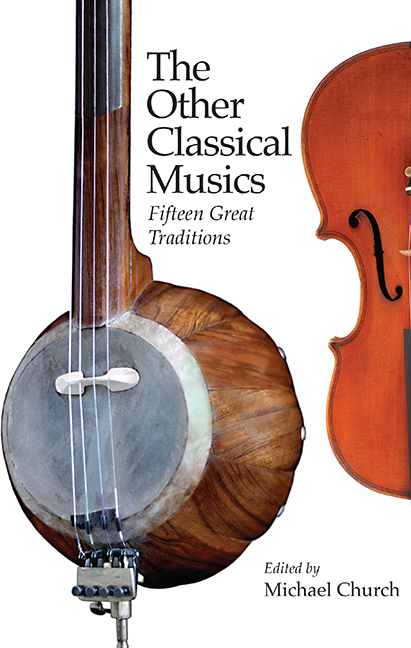

- The Other Classical MusicsFifteen Great Traditions, pp. 320 - 339Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015

- 1

- Cited by