4 - ‘That savage should mate with tame’: Hybridity, Indeterminacy, and the Grotesque in the Murals of San Miguel Arcángel (Ixmiquilpan, Mexico)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

Summary

Abstract

The murals that line the walls of the Augustinian convent church of San Miguel Arcángel in Ixmiquilpan (Hidalgo) together constitute one of the most important pictorial ensembles of early colonial Mexico. While these paintings have been understood both as a visual record of the voices of the subaltern and as a tool to aid Christian evangelization and conquest, the function of the grotesque in these works has been largely ignored. Drawing on period and modern understandings of the style, this chapter argues that, while the grotesque was used at Ixmiquilpan as a way to classify, control, and marginalize native culture, it simultaneously gave pictorial form to the unresolved, unclassifiable, dangerous, and protean realities of Christian evangelism in the New World.

Keywords: Mexico, evangelization, hybridity, New World, Augustinian, painting

The former Augustinian convent church of San Miguel in Ixmiquilpan (Hidalgo) is known for the sixteenth-century murals that decorate the lower walls of the nave. Located about 150 kilometres north of Mexico City, the church was constructed between 1550 and 1560 under the Augustinian prior Andrés de Mata, and the nave murals were painted by indigenous artists most likely in the late 1560s or early 1570s. Covered up at a later date, the murals were discovered in the late 1950s and subsequently have generated considerable scholarly attention.

Iconography and Context

The murals, which are located slightly above eye level and are over 2 metres in height, originally covered both sides of the nave and underchoir. Drawing on European decorative prints, they use the unifying motif of grotesque-inspired scrolling acanthus vines to depict a battle that pits figures with bows, centaur-like beings, dragons, and other fantastical creatures against warriors with shields and obsidian-edged clubs (Ills. 4.1 and 4.2). The latter are sometimes dressed in jaguar, coyote, and eagle costumes, the dress of the native warrior classes that continued to be worn during colonial festivals.

Given the references to native warfare, the fantastical creatures, and the absence of obvious Christian content, questions of iconography have dominated the literature. Most now agree that the work presents a psychomachia, a moralizing battle between good and evil. In such a reading the fantastic figures and warriors with bows represent the forces of evil, while the costumed figures and their allies embody the forces of good.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

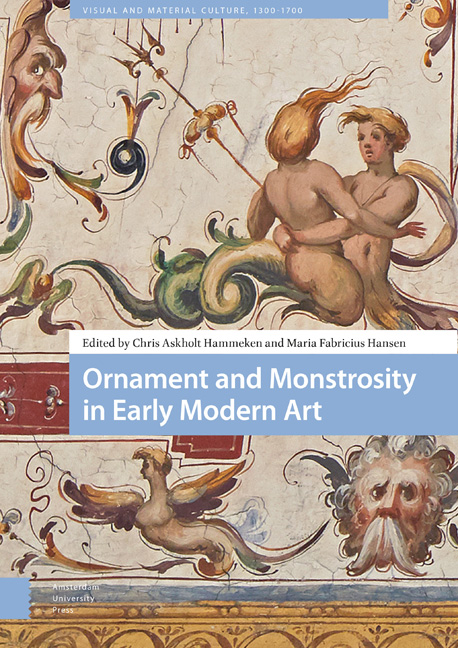

- Ornament and Monstrosity in Early Modern Art , pp. 133 - 152Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019