2 - Dissonant Symphonies: The Villa d’Este in Tivoli and the Grotesque

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 21 November 2020

Summary

Abstract

This chapter compares the architect and antiquarian Pirro Ligorio's theoretical writings on the grotesque with the garden that he designed for the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, paying close attention to the figure of Artemis of Ephesus depicted in the frescoes of the villa's interior and in the adjacent landscape where she appears as the Fountain of Nature. The fact that Ligorio was the author of an unusually detailed theory of grottesche and the designer of a garden that incorporates grotesque imagery makes his work an important case study of sixteenth-century attitudes towards ‘monstrous’ ornament in general and, more specifically, in landscape design.

Keywords: grotesque, gardens, Pirro Ligorio, Villa d’Este, Artemis of Ephesus

In his 1587 discussion of grottesche (‘grotesques’), the artist and writer Giovanni Battista Armenini describes an ancient underground chamber, or grotto, in which he had seen three paintings each framed by festoons of coloured fruit. In the first painting, three little satyrs appeared, one of whom carried another on his horse's back in ‘the way that children do in schools’. The third satyr was depicted beating the rider with a cabbage leaf. Another painting portrayed la Dea della Natura (‘the Goddess of Nature’) – a pictorial type derived from ancient cult statues of Artemis of Ephesus. Armenini writes that harpies were depicted in the third and final painting of the grotto's vault, their breasts transforming into leaves.

Paintings of this kind exerted a significant influence on sixteenth-century artists from the moment that they were rediscovered around 1480. They were soon referred to as grottesche owing to their discovery in what seemed to be subterranean caves or grottoes. The vast chambers of Nero's Domus Aurea, for example, which contained extensive ceiling and wall decorations in the grotesque style, had been filled in with earth during Antiquity, forming the foundations of the Baths of Titus and other subsequent structures. From the late fifteenth century, artists and scholars lowered themselves into the underground rooms of the villa so that they could examine the hybrid figures and metamorphic motifs by torchlight. A satirical rhyme of the period described how they ‘descend the grottoes with picnics and, “piu bizarri alle grottesche” [‘more bizarre than the grotesques’], crawl along the passages with toads, frogs, owls and bats.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

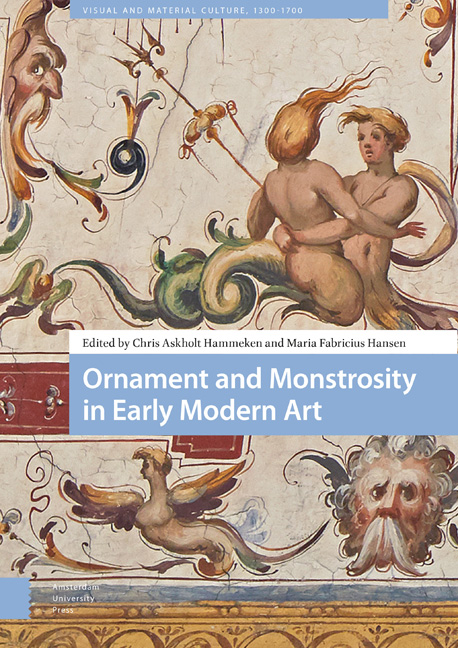

- Ornament and Monstrosity in Early Modern Art , pp. 73 - 92Publisher: Amsterdam University PressPrint publication year: 2019